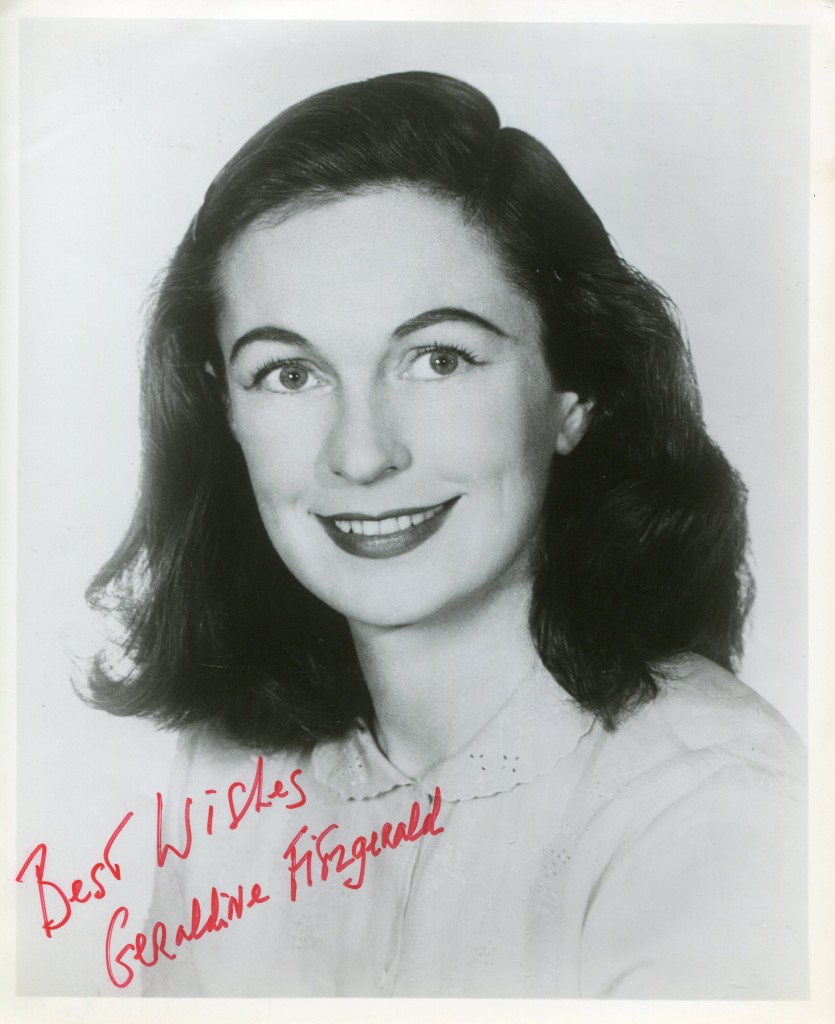

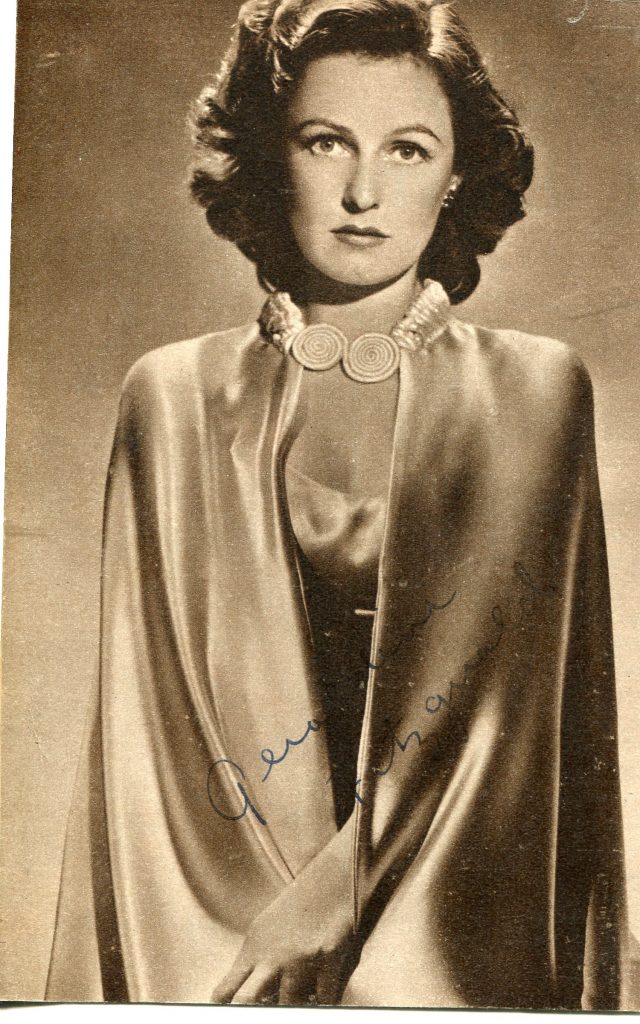

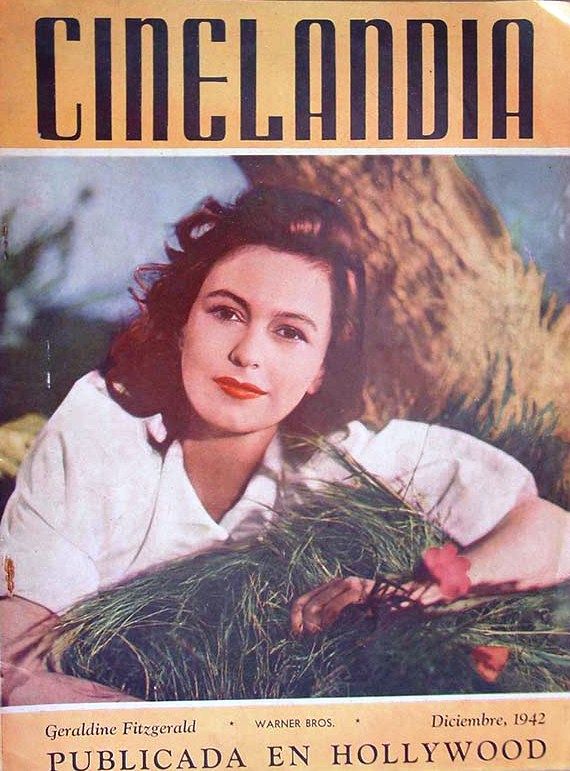

Geraldine Fitzgerald

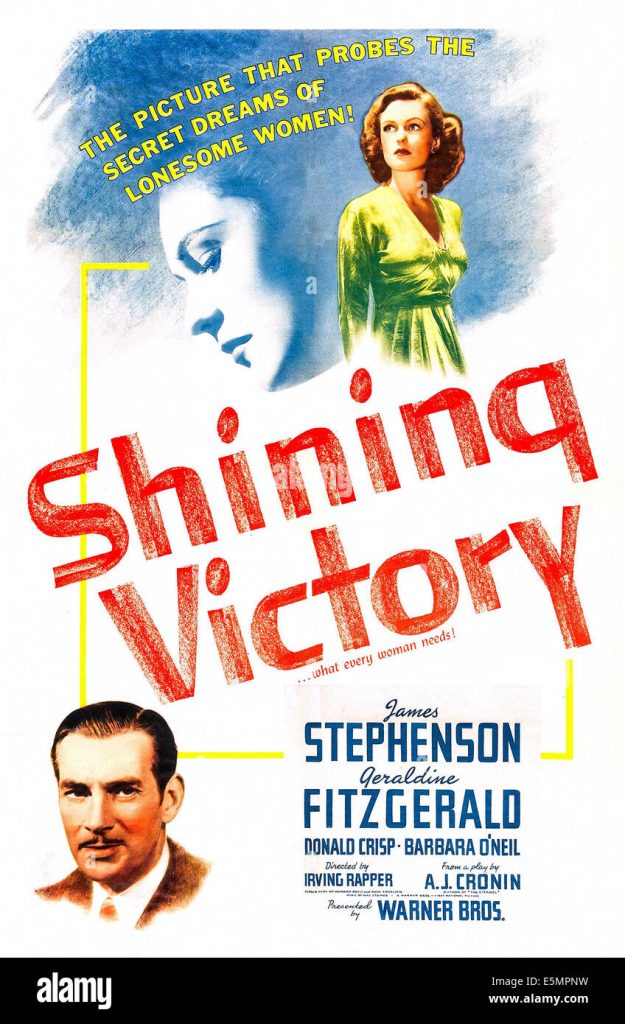

Geraldine Fitzgerald started her career with the Gate theatre in the 1930’s in Dublin. She was soon starring in such British films as “The Mill on the Floss”. By 1938 she was in Hollywood. Her first two films !Wuthering Heights” with Laurence Oliver and “Dark Victory” with Bette Davis both released the following year are now regarded as classics. Unfortunately she turned town the role of Brigidet O’Shaugnessy opposite Humphrey Bogart in “The Maltese Falcon” and her cinema career as a leading lady never recovered.

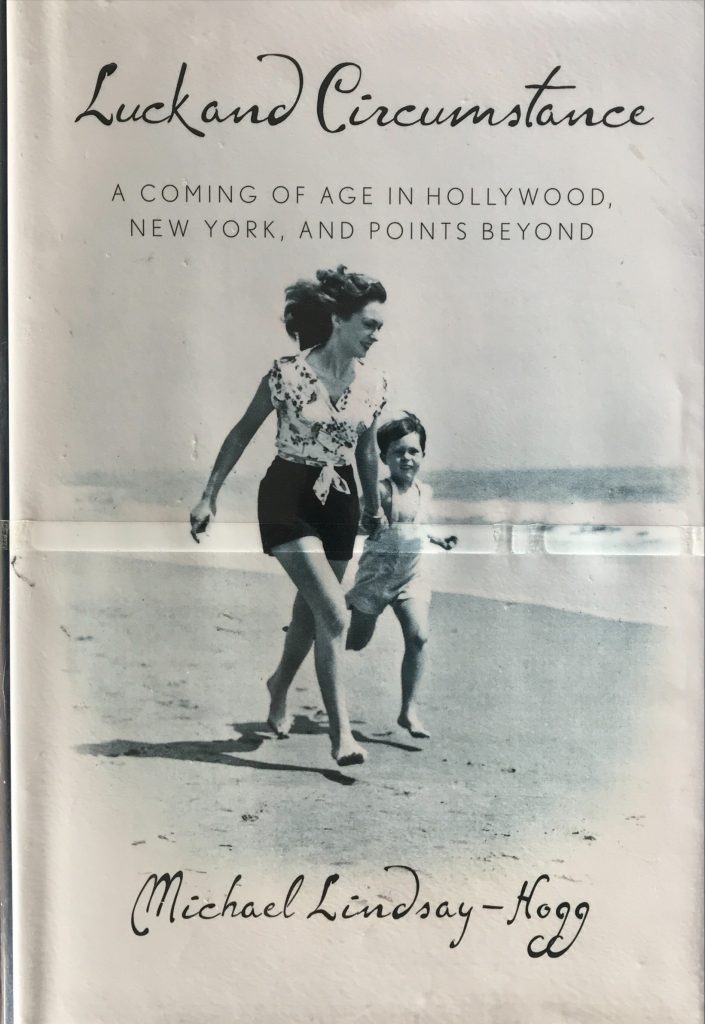

Geraldine Fitzgerald went to Broadway and developed into a consummate theatre actress. In the 1960’s she returned to Hollywood and became a very powerful character actress. Her son by her first marriage is the director Michael Lindsay-Hogg. Her second marriage was to Stuart Scheftel the grandson o the founder of Macys Department Store in New York. Geraldine Fitzgerald died in 2005 after a long battle with Alzhelhimer’s disease at the age of 91. Her performances are always intriguing and worth seeking out. She is of course, heavily featured in her son director Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s autobiography “Luck and Circumstance”.

The great Tennessee Williams made these comments about Geraldine Fitzgerald in an interview he gave in 1982 in New Orleans :

There was such a richness of character in those movies–all those fascinating character actors. I fell in love with Geraldine Fitzgerald in Dark Victory and Wuthering Heights. So much intelligence in every move, and so much detail. Her acting is like a knife in that it is so sharp and gleaming and capable of cutting all that is extraneous. I can’t think of a time in those films–and in all the work I’ve seen her do since–when there was even an ounce of superfluous detail: She sticks that knife–that dagger–of talent right into the heart of whatever part she’s playing. And then she’s done.

“Hollywood Players:The Forties” by James Robert Parish:

Geraldine Fitzgerald was singularly fortunate in her first two American made films. She made an auspicious Hollywood debut as Isabella Linton the desperate girl who made a fool of herself over the Heathcliffe of Laurence Oliver in William Wyler’s unforgetable “Wuthering Heights” in 1939. She was Oscar nominated for her performance but lost out to Hattie McDaniel for :Gone with the Wind”. Her two 1939 American features were very distinguished productions and no young actress could have had a more successful beginning to her film career. However Geraldine never became a goddess of the silver screen as expected. One of the reasons for this is that she fought the studio system before she was in a position to do so. While under contract to Warner Brothers she felt she was been exploited and turned down many roles which resulted in her been suspended a number of times. This type of action had worked for Bette Davis, a good friend of Geraldines, but Ms Davis was already an important money earner for the studio and Geraldine was not. As Geraldine told columnist Rex Reed “Humphrey Bogart always told me, movies were like a slot machine. If you played long enough, you would eventually hit the jackpot. which he did with the “Maltese Falcon”. But I was a fool. I stuck to my Irish logic instead. Instead of saying yes to everything, I fought Jack Warner for better parts and I finally lost.

TCM Overview:

A dark-haired classic beauty from the Dublin stage, Geraldine Fitzgerald had appeared in several British films before making her Broadway debut in the 1938 Mercury Theater production of George Bernard Shaw’s “Heartbreak House” and her Hollywood debut in “Dark Victory” (1939). She is perhaps best remembered for her splendid, Oscar-nominated supporting performance as Isabella, poignantly suffering the pangs of unrequited love, in William Wyler’s adaptation of “Wuthering Heights” (1939). Off to a fine start in Hollywood, Fitzgerald played strong-willed women throughout the 1940s. Among her notable performances was as one of the eponymous characters in the highly intriguing “Three Strangers” (1946), in which she more than held her own opposite Sydney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre. After being put on suspension for protesting too many dull studio-chosen roles, though, Fitzgerald found that by the end of the decade her screen career had virtually petered out.

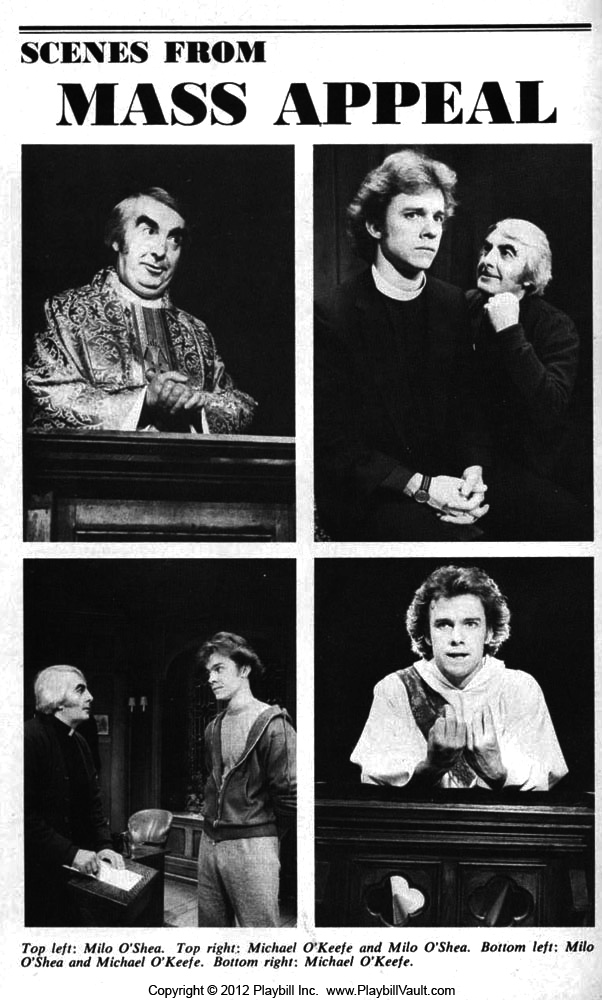

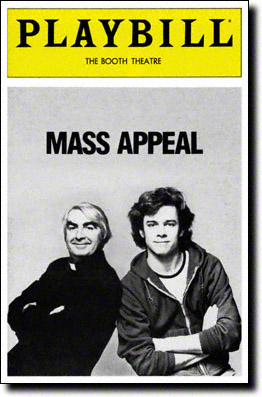

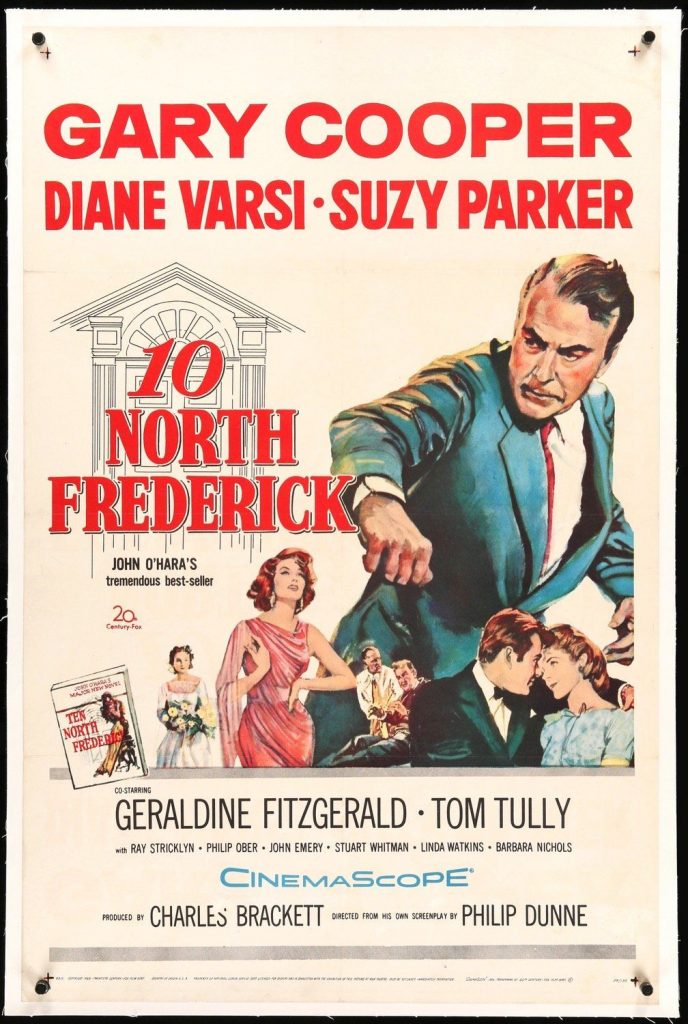

Geraldine Fitzgerald career slowed down somewhat during the 1950s and 60s, but she did TV and stage work, and made intermittent film appearances. She did fine work, for example, as the wife of a straying man (Gary Cooper) in “Ten North Frederick” (1958). In the 1970s, Fitzgerald made a triumphant return to the stage as an actress (in “Long Day’s Journey Into Night” 1971), director (“Mass Appeal” 1980, for which she received a Tony nomination) and street performer (with her Everyman Street Theatre). She was memorable in a brief turn as Dudley Moore’s wise grandmother in “Arthur” (1981) and also appeared in its inevitable, though inferior sequel, “Arthur 2: On the Rocks” (1988).

In 1988, she received an Emmy nomination for a guest spot as an elderly woman contemplating suicide on the long-running sitcom, “The Golden Girls”. Her son is director Michael Lindsay-Hogg.”Guardian” obituary by Ronald Bergan.When Geraldine Fitzgerald, who has died aged 91, directed her Tony-nominated production of Mass Appeal on Broadway in 1981, she explained: “I was forgotten, so I had nothing to live up to. It was the best thing in the circumstances. I could start at the bottom learning the new craft of directing.” It was a modest statement from someone remembered by film fans as a 1940s Hollywood star, and by playgoers for some classical performances in the 1970s.Born in Dublin, the daughter of a prominent lawyer – his firm, E&T Fitzgerald, was mentioned in James Joyce’s Ulysses – Geraldine was educated at a convent school.

Gifted in drawing, she persuaded her parents to enrol her at Dublin School of Art, whose head suggested marriage as the next step. Her shocked response was to take up acting, so she went to her aunt, Shelagh Richards, whom she had seen perform at the Abbey theatre, for coaching.Geraldine Fitzgerald began her acting career at the Gate theatre in 1932, where she met another aspiring beginner, the 17-year-old Orson Welles. He was infatuated by the fiery, auburn-haired beauty, six months his senior, and would later have a brief affair with her. She also bewitched Patrick Hamilton, who used her as the basis for the character of Neta in his 1941 novel, Hangover Square.

In 1934, Fitzgerald began acting in low-budget British films, notably Turn Of The Tide, about two feuding fishing families. In 1936, she married Edward Lindsay-Hogg, a horse breeder, and after she appeared as an effective Maggie Tulliver in The Mill On The Floss (1937), they moved to New York.

There, Welles gave Fitzgerald her American start, as Ellie Dunn in George Bernard Shaw’s Heartbreak House, with the 22-year-old Welles playing the octogenarian Captain Shotover, and a young Vincent Price as Hector Hushabye. The New York Times critic Brooks Atkinson found her showing nothing more than an ability to memorise lines; the producer, John Houseman, accused Welles of directing her with more indulgence than the rest of the cast.

Despite this, Geraldine Fitzgerald was offered the role of Isabella, to be seduced and abandoned by Laurence Olivier’s Heathcliff in William Wyler’s Wuthering Heights (1939), for which she was nominated for an Oscar as best supporting actress. On the strength of a sensitive performance, she got a contract with Warner Bros, for whom her first film was the classic weepy, Dark Victory (1939), in which she was touching as the devoted friend of dying Bette Davis.y

But Warner Bros failed to utilise Fitzgerald’s undoubted talent, casting her instead as second female leads, notably again with Davis in Watch On The Rhine (1943), to which she brought beauty and conviction as Countess Marthe de Brancovis, the unhappy wife of Nazi agent George Coulouris.

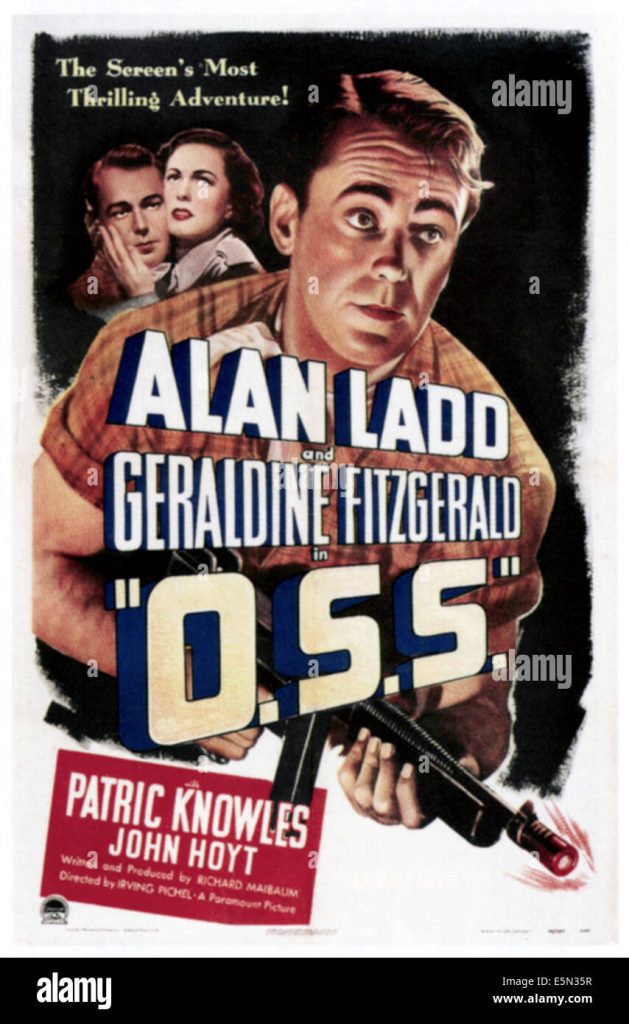

On loan to other studios, she was an upstanding US president’s wife in the biopic Wilson (1944), her first col-our film; the jealous spinster sister of George Sanders in Uncle Harry (1945), on trial for the murder of his fiancée; and calm and intense as Alan Ladd’s fellow spy in occupied France in OSS (1946).

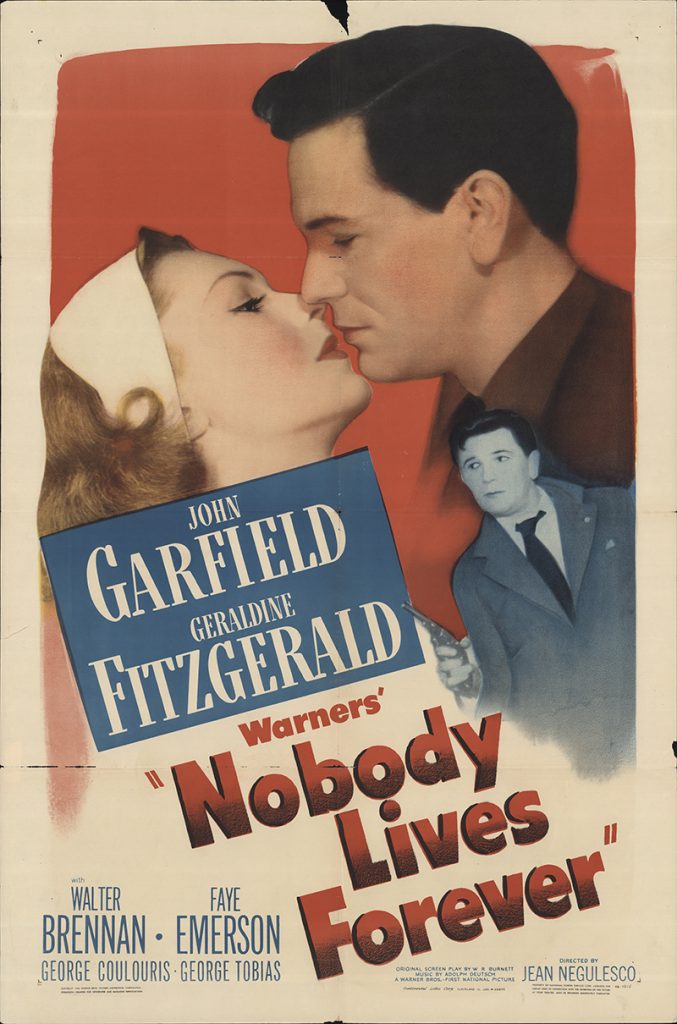

Her last two films for Warner Bros, both directed by Jean Negulesco, were Three Strangers (1945), in which she shared a sweepstake ticket with Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet, and Nobody Lives Forever (1946), playing a rich widow swindled out of a fortune by John Garfield. Yet even these leading parts did not bring her satisfaction, and her film career faded as she lost her battle with the studio bosses for more suitable roles.

It was disappointing, but Geraldine Fitzgerald hardly needed the money, having divorced Lindsay-Hogg in 1946 and married Stuart Scheftel, the businessman and grandson of the founder of Macy’s department store.

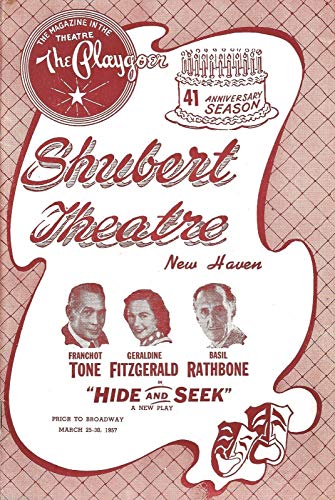

In 1955, she returned to the theatre, taking up again with Shaw, as Jennifer Dubedat in The Doctor’s Dilemma, and Welles, who cast her as Goneril to his King Lear in his ill-received production at the New York City Center. In 1961, she appeared off-Broadway in William Saroyan’s one-woman play, The Cave Dwellers, under the direction of her 21-year-old son, Michael Lindsay-Hogg.

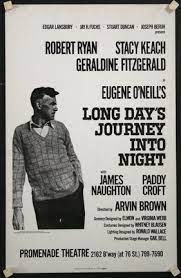

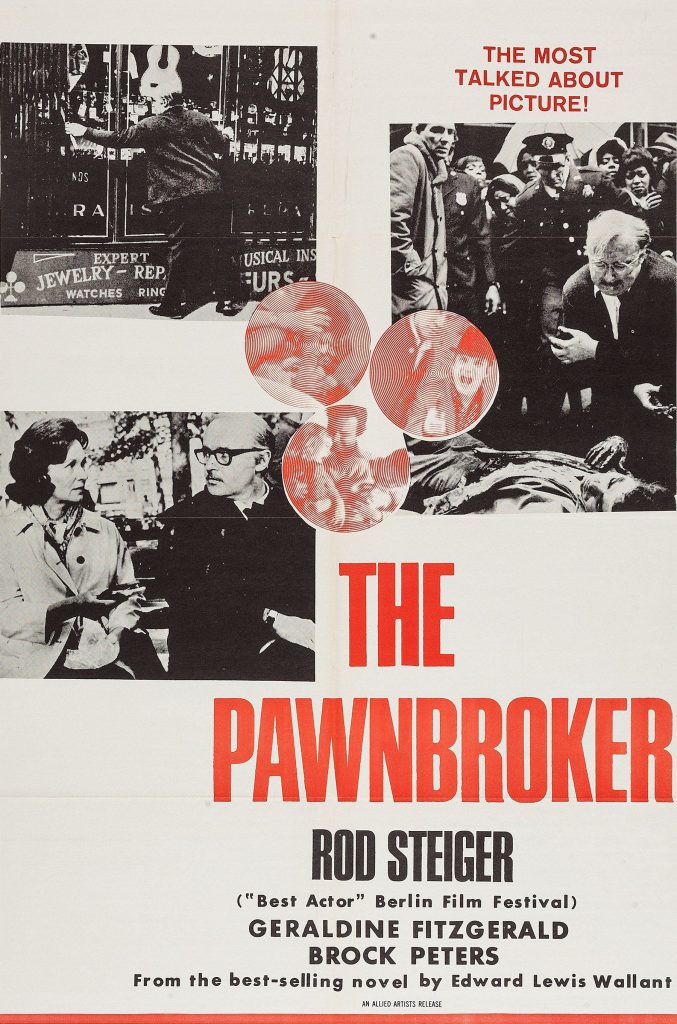

She worked only spasmodically in the 1960s, her few films including Sidney Lumet’s The Pawnbroker (1965) and Paul Newman’s Rachel (1968), in which she played a revivalist preacher. But, in 1971, she made a triumphant comeback off-Broadway as Mary Tyrone, the drug-addicted mother in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night, winning a New York Critics’ award.

Geraldine Fitzgerald continued to be very active in the 1970s and 80s, making an impression on stage as Aline Solness in Ibsen’s The Master Builder, and as Amanda Winfield in Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie, as well as singing Irish folk songs in a one-woman cabaret show. Her screen performances included a moving old lady in Harry And Tonto (1974); a love scene with Gérard Depardieu in Bye Bye Monkey (1978); the role of a billionaire matriarch in Arthur (1981) and Arthur 2: On The Rocks (1988); a clairvoyant in Poltergeist II (1986); and the presidential matriarch Rose Kennedy on television in 1983.

During the run of Fitzgerald’s Mass Appeal, Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s production of Agnes Of God opened, making it the first time that two directors, mother and son, had separate plays running on Broadway at the same time.

Scheftel died in 1994; their daughter Susan survives her, along with Michael.

Brian McFarlane’s entry in “Encyclopedia of British Film”:

One of the most beautiful women in British films of the 1930s, she was an archtypical Irish redhead with green eyes, perfect features and a slightly husky voice, along with an incisive acting talent, what was British cinema to do witl all of this? The answer, is sadly very little. Oly the “Mill on the Floss” in 1937 as afindvivid ‘Maggie Tullivar’ challendged her.

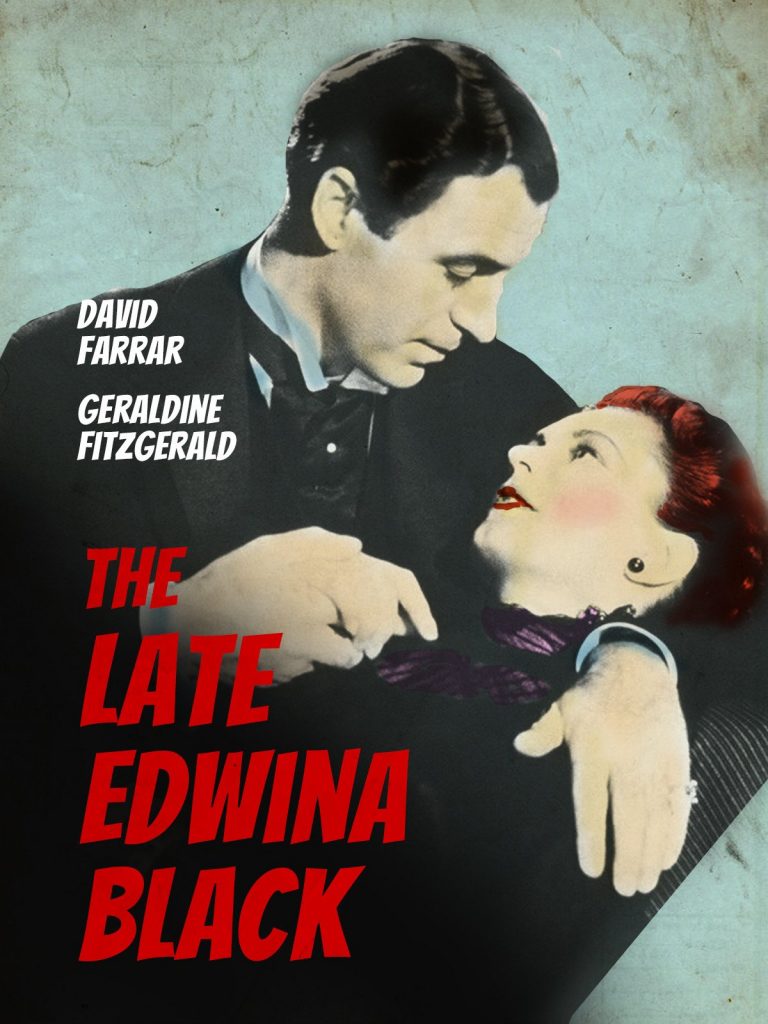

After that, she was whisked off to Hollywood to play ‘Isabella’ in “Wuthering Heights” in which she alone looked like she had read the book. She had interesting roles in the US like in “Wilson” but always looked too intelligent for major stardom. Filmed in England only twice more, as the tippling adulteress in “So Evil, My Love” and the suspected companion of “The Late Edwina Black” in 1951. She became a potent stage actress in the US.

For “The Guardian” obituary on Geraldine Fitzgerald, please click here.

Lovely video tribute on Geraldine Fitzgerald & “Wuthering Heights” here.

New York Times obituary in 2005.

Geraldine Fitzgerald, a feisty, gravel-voiced Dublin redhead who drew instant acclaim in her first Hollywood films, including a 1939 Oscar nomination for “Wuthering Heights,” before carving out a long, varied career in films, television, cabaret and theater, died on Sunday afternoon at her home on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. She was 91.

She had Alzheimer’s disease for more than a decade and was essentially incapacitated in recent years, leading to a respiratory infection that finally killed her, said her daughter, Susan Scheftel, a clinical psychologist in New York.

Ms. Fitzgerald appeared on the New York stage and as a highly coveted character actress in dozens of Hollywood films, including “Watch on the Rhine” in 1943, “Ten North Frederick” in 1958, “The Pawnbroker” in 1964, “Harry and Tonto” in 1974 and “Arthur” in 1981. But she may have been best known in New York for what many critics considered one of the definitive Mary Tyrones, opposite Robert Ryan, in a 1971 revival of Eugene O’Neill’s “Long Day’s Journey Into Night.”

Witty and intelligent, she was also notoriously combative and blamed herself for sabotaging her early Hollywood success by battling with studio executives over roles. “My mother was just way too feisty to be in bondage to the Warner Brothers,” Ms. Scheftel said.

Born in 1913, the daughter of a Dublin solicitor, Geraldine Fitzgerald was drawn into the legendary Gate Theater by her aunt, Shelagh Richards, one of its stars. Ms. Fitzgerald performed there alongside James Mason and Orson Welles. She married Edward Lindsay-Hogg, an Irish aristocrat, and after a stint at art school in England she moved to New York in 1938 to further her husband’s songwriting ambitions.

Money grew tight, and she noted that her old friend Welles was directing something called the Mercury Theater. She called and he hired her for a role in “Heartbreak House.”

Norman Lloyd, a longtime friend and founding member of the Mercury Theater, described the effect she had. “She was a staggeringly beautiful girl with the most delightful speech, a slight Irish tinge, not a thick brogue, and this glorious red hair,” he said.

Hal Wallis, a major Hollywood producer, saw her in Shaw’s “Heartbreak House” and signed her to a Warner Brothers contract. She was told to play best friend to the dying Bette Davis in “Dark Victory” (1939), and her performance persuaded Samuel Goldwyn to cast her as the tragic Isabella Linton in “Wuthering Heights.”

In the 1940’s she mingled with Hollywood’s intellectual elite, counting among her friends Laurence Olivier, Charlie Chaplin, Davis, Welles and the screenwriter Charles Lederer.

When World War II separated Ms. Fitzgerald from her husband, then back in England, she stayed in Los Angeles with their son, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, later to become an acclaimed film, television and Broadway director. Her first marriage ended in 1946.

By then, she had worked her way up to leading roles. A performance as Woodrow Wilson’s wife, Edith, in “Wilson” (1944) earned her a glamorous photo on the cover of Life magazine. It also attracted the attention of Stuart Scheftel, the grandson of Isador Straus, the co-owner of the R.H. Macy Co. who went down with the Titanic. Scheftel asked a friend to introduce them, and they were married in 1946.

They moved to New York and joined the rarefied circles in which the city’s cultural and political worlds mingled. The couple stayed together until his death in 1994.

She continued to work steadily and in the 1960’s formed the Everyman Street Theater, which ventured into the city’s poorest neighborhoods to recruit and train street performers. This led to an interest in directing, and she staged several productions, including all-black productions of O’Neill classics. In 1982, she received her only Tony nomination, as a director, for “Mass Appeal.” Among the directors she aced out of a nomination that year was her son, who staged “Agnes of God” a couple of blocks away. He survives her, along with Ms. Scheftel, two grandchildren and one step-grandchild.

In the 1970’s, after a small role in “Rachel, Rachel” required her to sing on camera, the unpleasant results caused her to take voice lessons. Thus she began yet another career, as a cabaret artist. Her show “Streetsongs” was a nightclub hit and appeared three times in Broadway theaters over the years.

When young actresses went to her for advice, she remembered her own regrets about having looked down her nose at early Hollywood offers. “Her advice to young actresses was to always say yes,” Ms. Scheftel said. “She had learned that the hard way by saying no all the time. So she would tell them, when offered work, always say yes