Dorothy Malone obituary from “The Guardian” in 2018.

Best Replica Watches UK Online Store bestfastwatches.com,High-end Grade AAA+ 1:1 Replica Rolex Watches Swiss Made.

Mit dem Ziel, den Anforderungen deutscher Uhrenliebhaber gerecht zu werden, stellt bestuhren.de sicher, dass Kunden auf eine Vielzahl von replizierten Uhren zugreifen können, die sich durch erschwingliche Preise und hervorragendes Handwerk auszeichnen.

regwatches.com is the world’s leading manufacturer of high-quality replica watches.

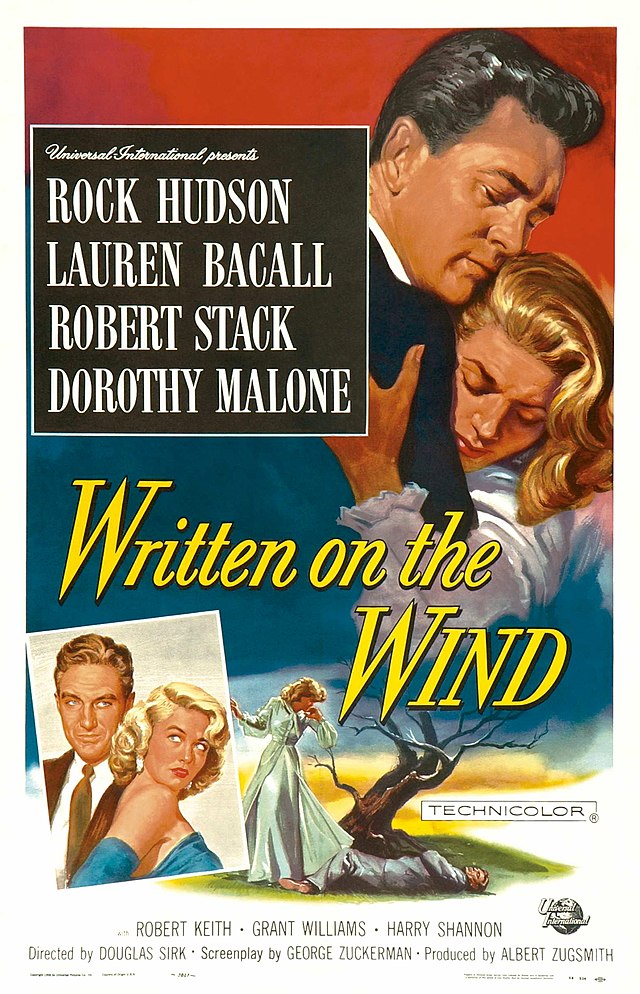

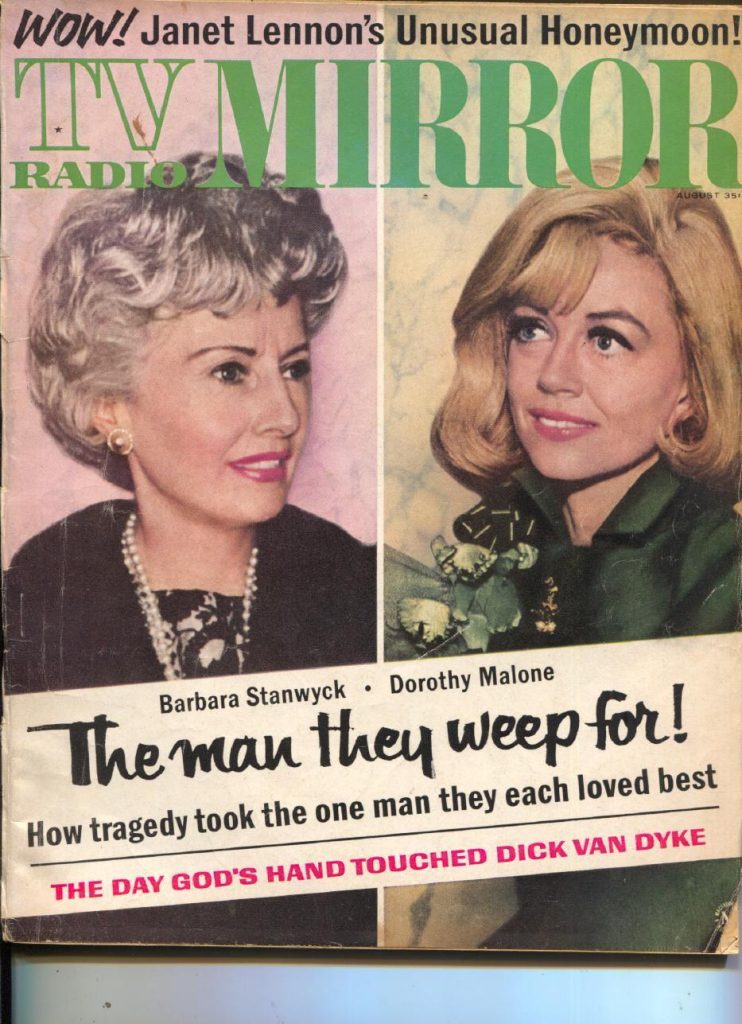

The Hollywood star Dorothy Malone, who has died aged 92, appeared in only a handful of works of distinction in a fairly lengthy career, however they are good enough to secure her place in film history. On those occasions when the role permitted, most notably in two flamboyant melodramas directed by Douglas Sirk, Written on the Wind (1956) and The Tarnished Angels (1957), Malone revealed what a talented performer she could be, one capable of projecting a potent blend of cynicism, sexuality and intelligence. However, she was probably most familiar to the general public as Constance MacKenzie in Peyton Place (1964-68), one of the first primetime TV soap operas.

In Written on the Wind, Malone played Marylee, an oil heiress, sister of an alcoholic playboy Kyle Hadley (Robert Stack). She’s in love with Kyle’s best friend Mitch (Rock Hudson), but he’s in love with Kyle’s pregnant wife Lucy (Lauren Bacall). Jealous, Marylee convinces Kyle that Lucy’s baby really belongs to Mitch. Her wild erotic dance to a loud mambo beat, intercut with scenes of her father’s fatal heart attack, is one of the great sequences of 1950s Hollywood melodrama. “It was a miracle that I got her to do the scene,” Sirk recalled. “She was very prudish … I even had to watch my language. If I said, ‘This scene needs more balls’, she’d walk off the set.” Malone, upstaging even Bacall, won the best supporting actress Oscar.

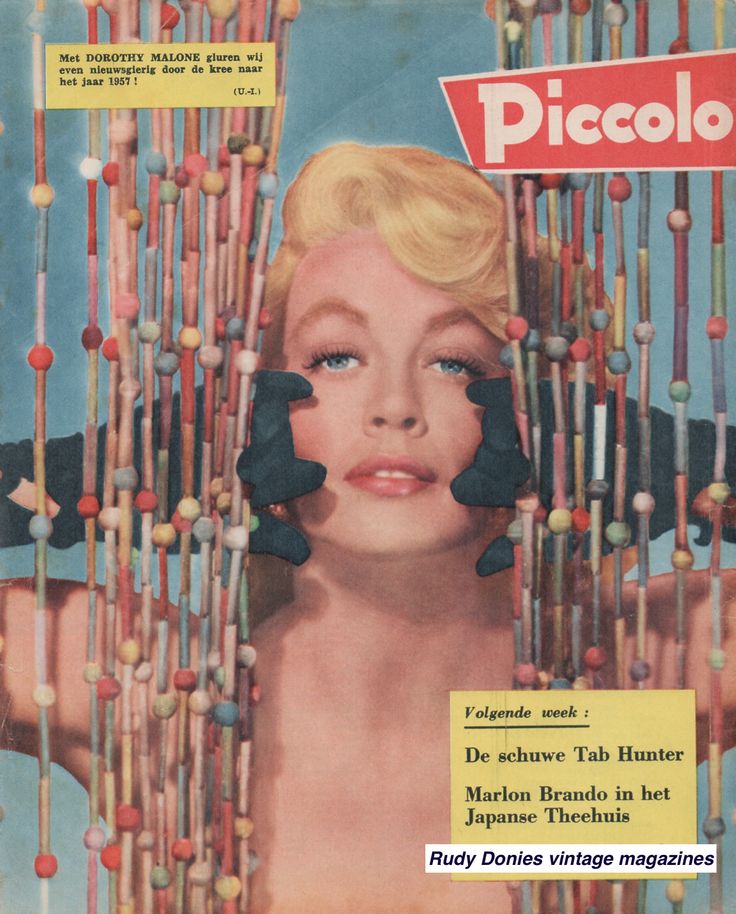

Sirk reunited Malone, Hudson and Stack for The Tarnished Angels, skilfully adapted from the William Faulkner novel Pylon. Stack played a daredevil pilot performing at air shows with Malone as his neglected parachutist wife. She is the film’s fulcrum – vulnerable, naïve and yet with a fierce sexuality – caught between her disillusioned husband and a run-down alcoholic journalist (Hudson). The latter reacts towards her with a mixture of lust and pity, bragging that he “sat up half the night discussing literature and life with a beautiful, half-naked blonde”.

She was born Dorothy Maloney in Chicago and brought up in Dallas, Texas, one of five children of Robert Maloney, an accountant, and his wife, Esther (nee Smith). She attended Ursuline Convent and Highland Park high school, both in Dallas. Following graduation, she studied at Southern Methodist University with the intention of becoming a nurse, but a role in a college play happened to catch the eye of an RKO talent scout and, aged 18, she was offered a Hollywood contract.Advertisement

The studio gave her nothing more than bit parts in eight movies for a year, so she switched to Warner Bros. Among Malone’s first films at Warners was Howard Hawks’s classic film noir The Big Sleep (1946) in which, despite appearing in a single sequence lasting a little over three minutes, she made a huge impact. The scene, which Hawks considered cutting because it was not indispensable to the complicated plot, was saved, according to the director, “just because the girl was so damn pretty”.

It involved the private eye Philip Marlowe (Humphrey Bogart), on a case, popping into a bookshop run by Malone, to find out if she knows the suspicious owner of a rival bookshop across the road. She is bespectacled and wears her hair up – a Hollywood signifier of an intellectual – though she seems to be flirting with him. “You begin to interest me … vaguely,” she says. Marlowe starts to leave, but it is raining outside and when she says, “It’s coming down pretty hard out there,” something in her voice suggests she wants him to stay.

“You know, as it happens I have a bottle of pretty good rye in my pocket,” he says. “I’d a lot rather get wet in here.” She puts the closed sign on the door, lowers the shade, takes her glasses off and lets down her hair. “Looks like we’re closed for the rest of the afternoon,” she says. Audiences were left to make up their own minds about what happened next.

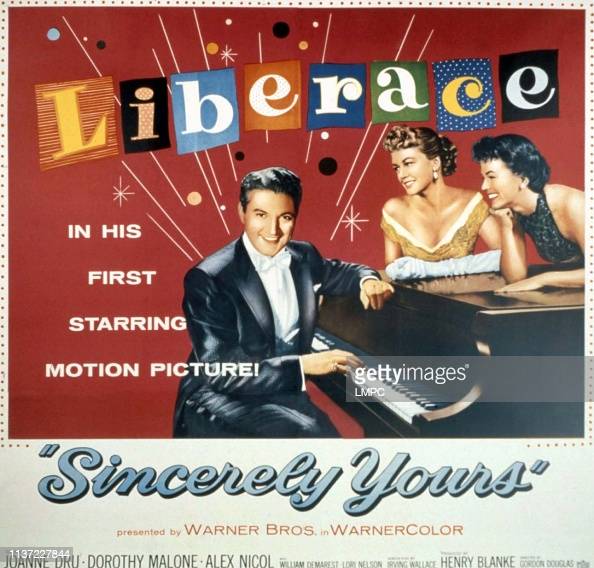

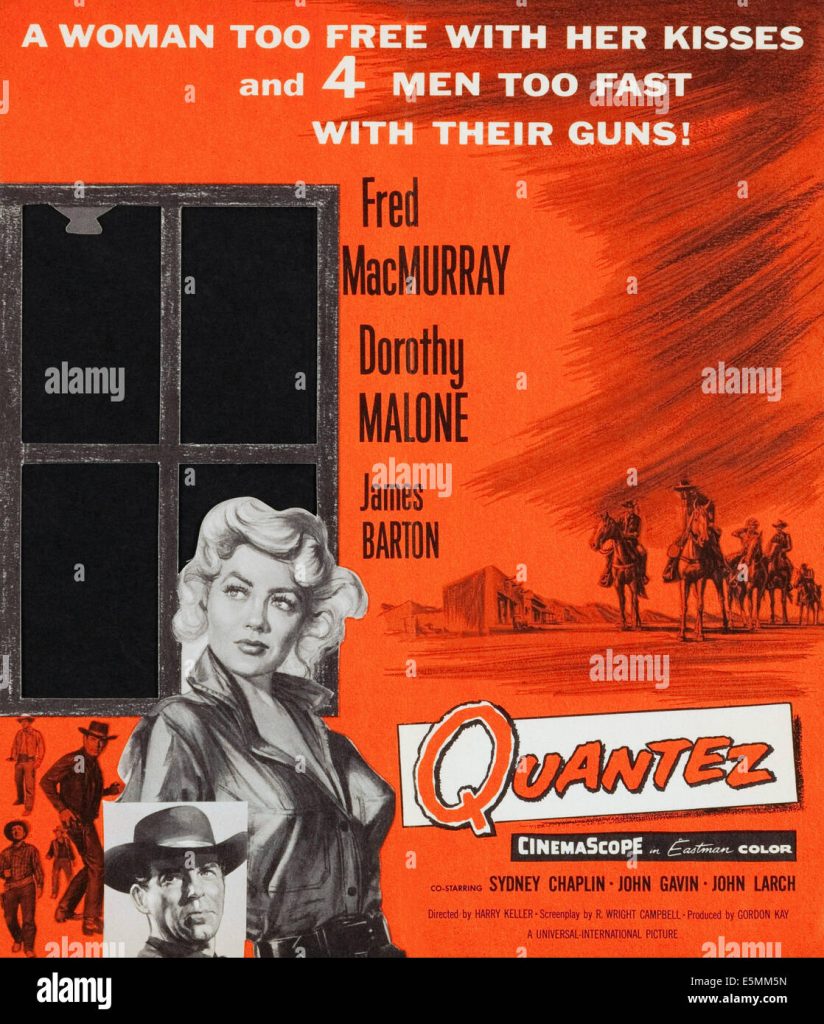

Unaccountably, what happened next in Malone’s career were parts that failed to exploit her subtle sensuality. She sang In the Still of the Night in the fanciful biopic of Cole Porter Night and Day (1946), and played “nice” girls in a string of film noirs and westerns, subverting her persona slightly in Raoul Walsh’s Colorado Territory (1949), the splendid western remake of his earlier gangster movie High Sierra. In it, Malone is the “good” girl who betrays her boyfriend, a wanted robber (Joel McCrea), in order to get the reward money.

Malone had a small but pivotal role as Kim Novak’s helpful neighbour in Richard Quine’s taut film noir Pushover (1954), before becoming a platinum blonde to play Doris Day’s sister in Young at Heart (1954), and the married woman with whom a soldier (Tab Hunter) has a fling while on leave in Walsh’s Battle Cry (1955). In contrast, Malone appeared to enjoy herself in one of her rare comedies, as a “lady cartoonist” in Frank Tashlin’s Artists and Models (1955), one of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis’s better efforts.

After Written on the Wind and The Tarnished Angels, Malone’s career was on a new track with offers of more meaty roles such as those in two biopics: Man of a Thousand Faces (1957), in which she was convincingly unsympathetic as the first wife of the silent screen star Lon Chaney (James Cagney); and Too Much Too Soon (1958), riveting as Diana Barrymore, ruined by drink, drugs and bad relationships, and by being the daughter of the actor John Barrymore (Errol Flynn).

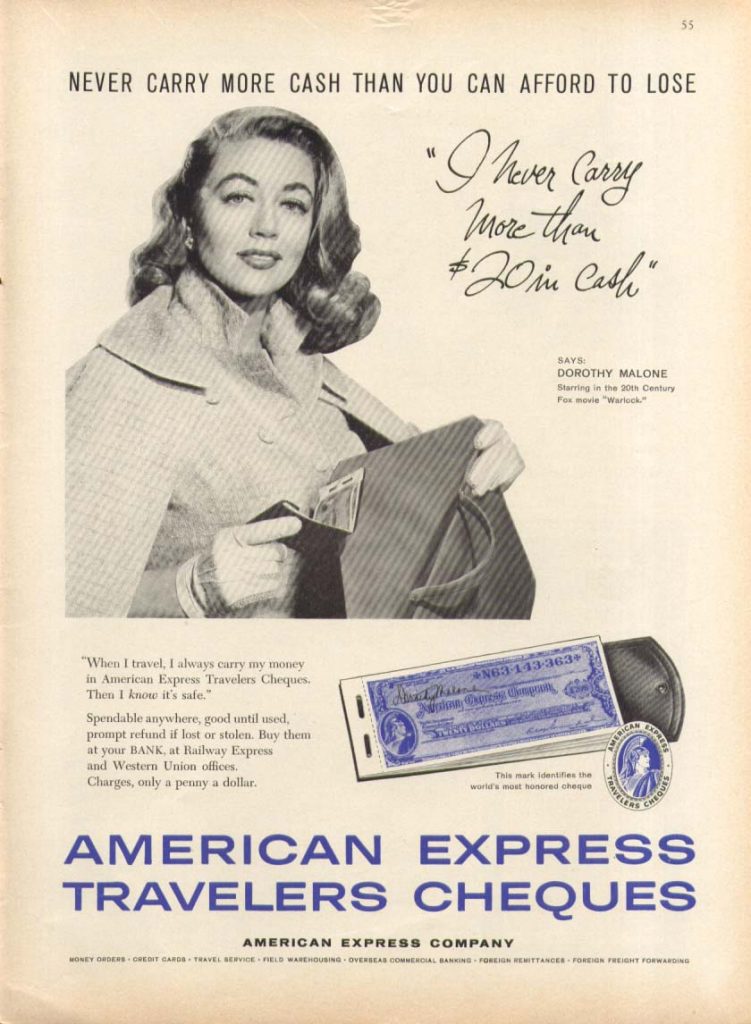

She followed these pictures with two intriguing multilayered psychological westerns, Edward Dmytryk’s Warlock (1959), in which Malone was Lily Dollar, arriving in the eponymous town, accusing the marshal (Henry Fonda) of murder; and Robert Aldrich’s The Late Sunset (1961), as the old flame of an outlaw (Kirk Douglas), not telling him soon enough that he is the father of her pretty teenage daughter (Carol Lynley).

Meanwhile, she had married Jacques Bergerac, Ginger Rogers’s ex-husband, in 1959. The stormy marriage lasted less than five years, with Malone winning custody of their two daughters, Mimi and Diane, after a bitter battle. After the divorce, her dynamic presence was felt mostly on the small screen, especially displaying her Sirkian credentials as a domineering mother in Peyton Place. However, after four years of much bickering with producers, she was written out of the show. She sued for breach of contract and eventually settled out of court.

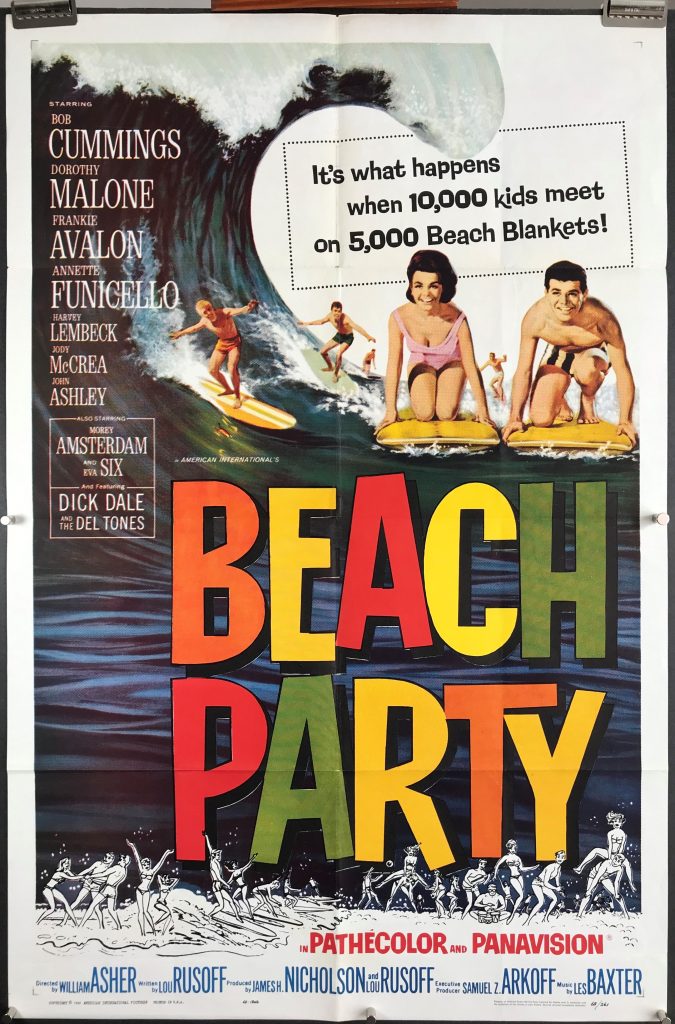

After that she worked steadily in television, guest-starring in dozens of series, with occasional forays into films. Her last film role was as Hazel Dobkins, the family-murdering friend of Catherine Tramell (Sharon Stone) in Basic Instinct (1992).

Ms Malone married and divorced twice more. She is survived by her daughters, Mimi and Diane, six grandchildren, and her brother, Robert.

• Dorothy Malone (Dorothy Eloise Maloney), actor, born 30 January 1925; died 19 January 2018