Wendy Hiller obituary in “The Guardian” in 2003

Wendy Hiller who has died aged 90, was stage-struck from the word go. It was the atmosphere, the teamwork – being there was everything.So in 1930 she joined the Manchester Repertory Theatre, Britain’s first such company. As a student, young Wendy was proud to be a dogsbody. Whatever came her way she did with a will: sweeping the stage, making the tea, setting the scenery, prompting, walking on.

What could be better? But one day she was sacked, and went home to Bramhall, Cheshire, to mope.

However, by chance, one of the company had adapted a book. Walter Greenwood’s novel Love On The Dole was set in the Depression; and the heroine needed a good Lancashire accent. Hadn’t the girl they had just fired been good at that sort of thing?

After touring from May to November 1934 in Ronald Gow’s adaptation, she became famous overnight when the play moved to London (in 1935) and New York (in 1936). It was the authenticity of her northern speech that did it: that and her frank, matter-of-fact manner as Sally Hardcastle, the mill girl ready to face a fate worse than death rather than have her family go hungry.

Not that the actor herself came from a poor family. Her father was a prominent cotton manufacturer, who had believed that unless she was rid of her Lancashire accent she stood no chance of marrying; so she had been dispatched to Winceby House school, Bexhill, to lose it.

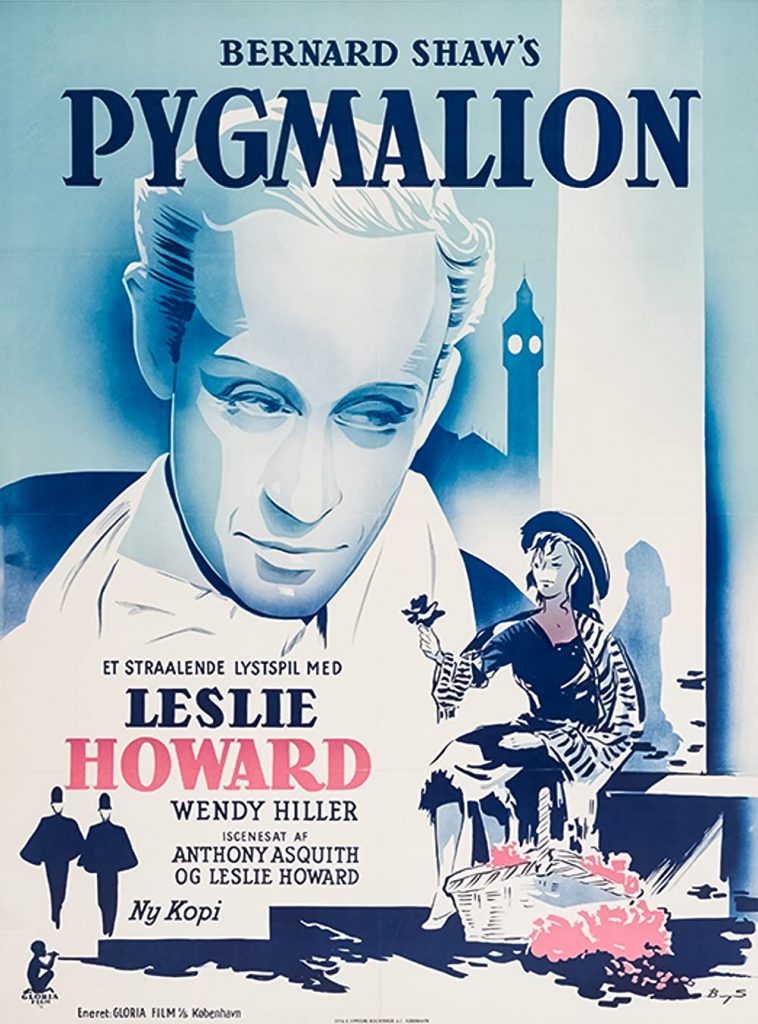

In the London run, James Agate judged her Sally Hardcastle “magnificent”. The play “moved me terribly and must move anybody who still has about him that old-fashioned thing – a heart”. And the fate worse than death? It was Sally’s acceptance of an offer from a married bookmaker to provide for her and her family if she became his nominal housekeeper. In 1937, the actor in fact married her author, Ronald Gow, and her film triumph as Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion (1938) came after playing both that role and Saint Joan at the Malvern festival for Bernard Shaw in 1936.

Whether it was her voice that made her fortune with its inimitable earthy quality, at once gritty and quavering, tremulous but clear in its deliberative phrasing, or whether the direct, no-nonsense northern personality of a girl to whom success came almost inadvertently, her temperament was to make all her acting seem honest, open, trustworthy and unaffected. This air of emotional integrity was to compel our attention for the next half century. Yet her speech, with its peasant inflections and hesitations, was crucial because its regional range was so hard to pin down – Lancashire for Sally Hardcastle, Bow Bells for Eliza Doolittle and Hardy’s Wessex for Tess Of The D’Urbervilles.

This was her next triumph. Again, the adaptation was by Ronald Gow, and to my mind it was her finest stage performance. In its sensibility, sincerity, passion and tragic power, there was nothing on the London stage to match it. It came for a week to St Martin’s Lane from the Bristol Old Vic in 1946, returning for a West End run in 1947. And though Gow deserved high praise for his handling of the novel, it was his wife who stole all our hearts with her rustic simplicity and emotional truth.

This ability to express transparent honesty astonished everyone. It was so hard, as one critic observed, not to believe in her. An actor may harbour heaps of personal sincerity, but unless she can transmit it to us she might as well be without it.

What continued to impress the student of acting was the way she went on to interpret – without perhaps ever excelling her role as Tess – everything from Shakespeare, lbsen, Shaw, Synge, Wilde, O’Neill and Henry James to Somerset Maughan, Robert Bolt, Royce Ryton and Alfred Uhry. Plain women or pretty, queens or flower girls, princesses or imprisoned spinsters, dominant wives or meek daughters.

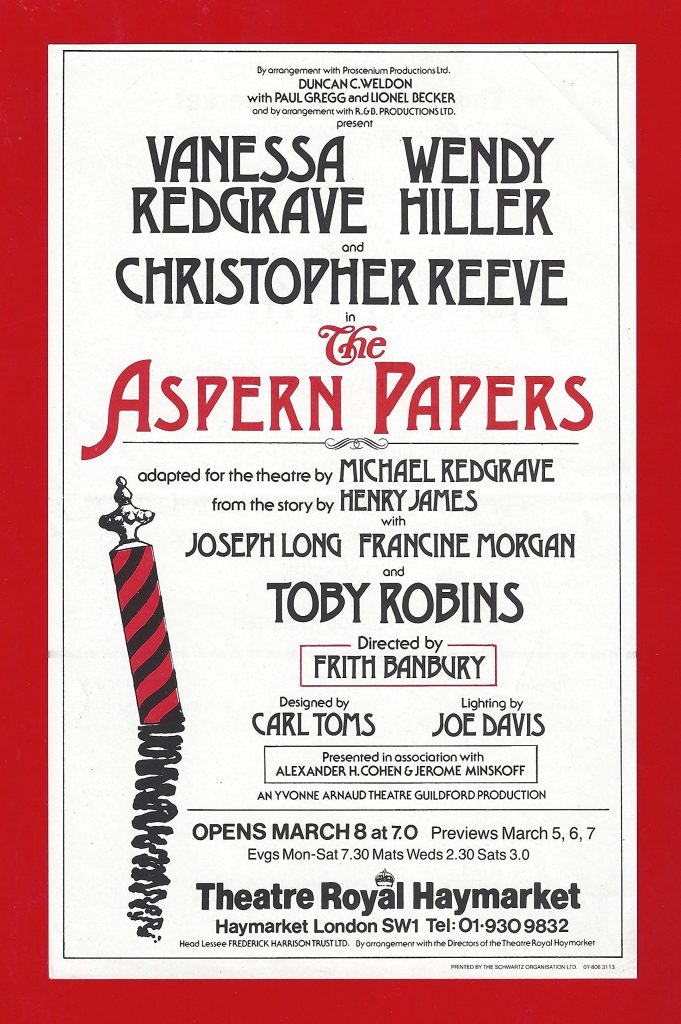

Hiller had a particular feeling for supposedly unattractive women like Catherine Sloper in The Heiress (New York, 1947; Haymarket, 1950), perhaps because she knew she was no conventional beauty; taking over, in London, from Peggy Ashcroft as Evelyn Daly, the daughter and maid-of-all-work in NC Hunter’s Waters Of The Moon (Haymarket, 1951); or in the same play at Chichester 27 years later as the supremely fussy Mrs Whyte, of the expressive knitting needles; or as the deferential Miss Tina in Michael Redgrave’s version of The Aspern Papers (New York, 1962); or, 22 years later in the same play at Chichester, as the fierce and ancient Miss Bordereau.

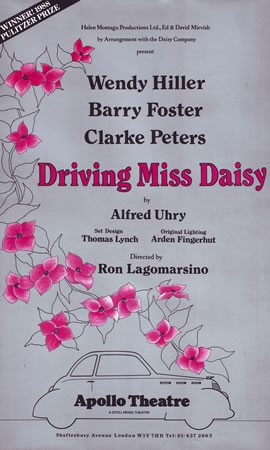

Perhaps two of the most conspicuous surprises of her career came with her icy hauteur as a majestic Queen Mary in Royce Ryton’s version of the abdication crisis, Crown Matrimonial (Haymarket, 1972); and 16 years after that as an august, irascible American widow learning to live with her black chauffeur in Alfred Uhry’s Pulitzer prize-winning play, Driving Miss Daisy (Apollo, 1988).

If Hiller never reached the heights as a Shakespearean actor, it was perhaps that the voice seemed too hard and the diction disjointed, though for the Old Vic (1955-56) she had plenty of passion for Portia in Julius Caesar. Watching her deeply moving Hermione in The Winter’s Tale, purists might complain of the poetry being cracked; but then the character itself was on the point of breakdown because the force of her anguish – dignity hanging on a thread – had brought the woman to the verge of physical collapse.

As Emilia to John Neville and Richard Burton alternating the parts of Othello and Iago, Hiller struck, as a critic put it, “fire from the tinder of the woman’s grief, rage and disillusion”; and as Helen in Tyrone Guthrie’s modern-dress Troilus and Cressida, the actor set the house on a roar as a vapid Edwardian beauty playing a waltz at the piano.

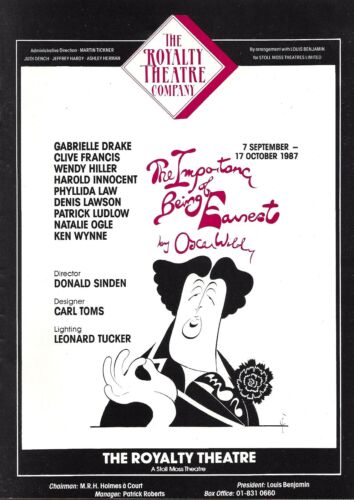

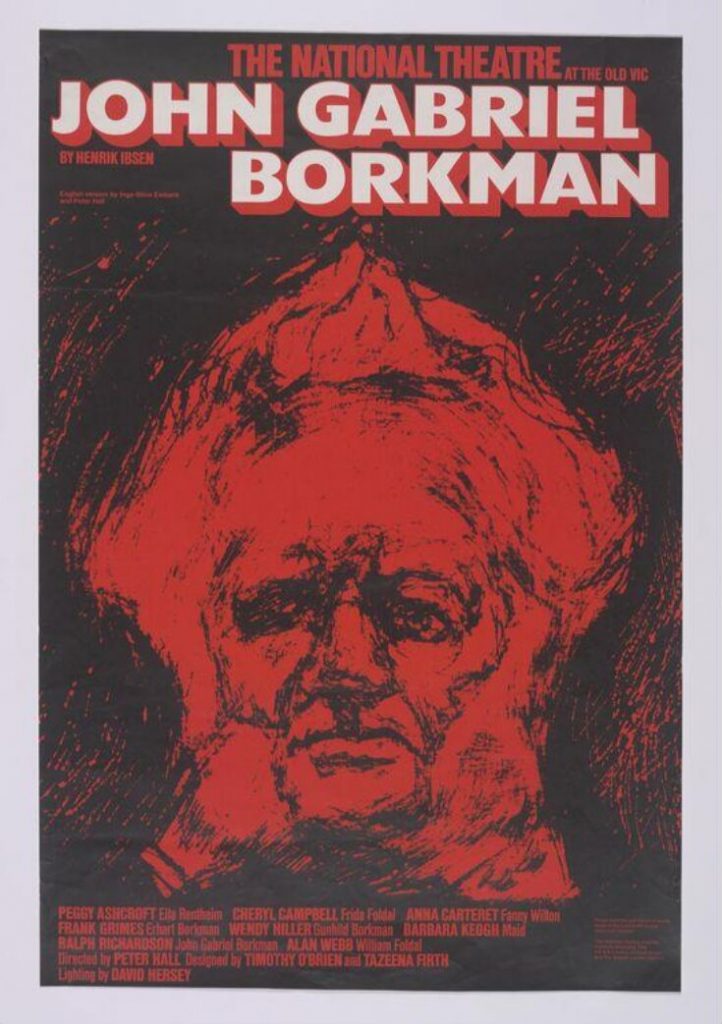

If the ventures into lbsen were less remarkable – When We Dead Awaken (Edinburgh Festival, 1968), Mrs Alving in Ghosts (Arts, Cambridge, 1972) and Mrs Borkman for the National Theatre (1975-76) – you could count on the power of her grief; though the irony of her comedy playing was something to savour, perhaps because it was scarcer. Her deliberative delivery as Lady Bracknell in The Importance Of Being Earnest (Watford, 1981) had us hanging on every word without reference to Edith Evans.

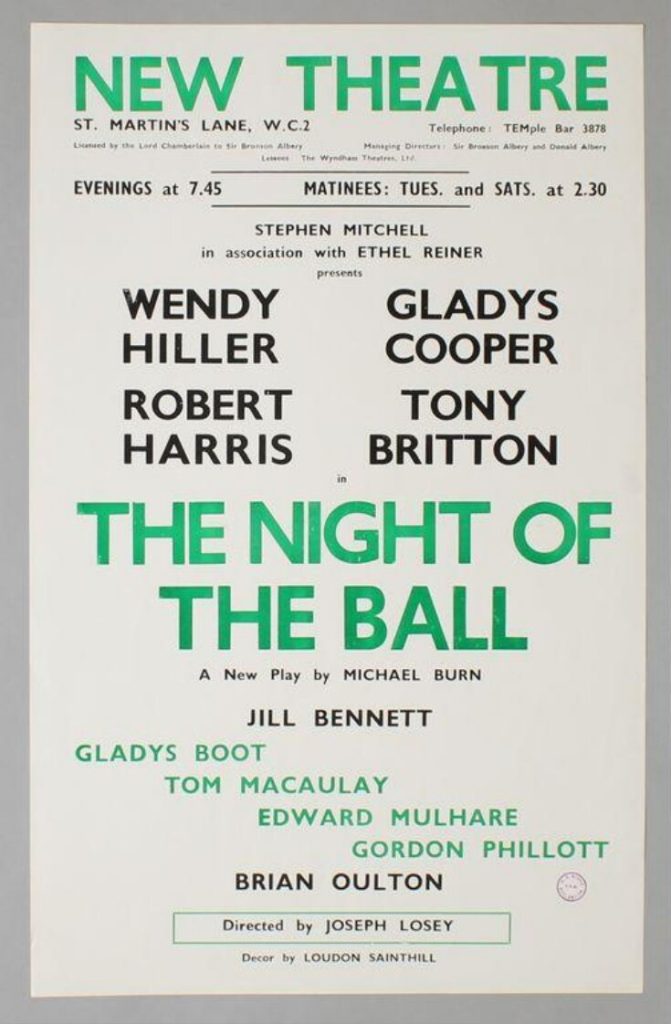

Even opposite one of the most ruthlessly accomplished exponents of considered speech, Robert Morley, as the Prince Regent, to her ill-fated, independent Princess Charlotte in Norman Ginsbury’s The First Gentleman (New, 1945) the young actor held her own in a rivetting duel of personalities which to my mind she won on points – as if to illustrate the difference between acting for effect and acting for truth.

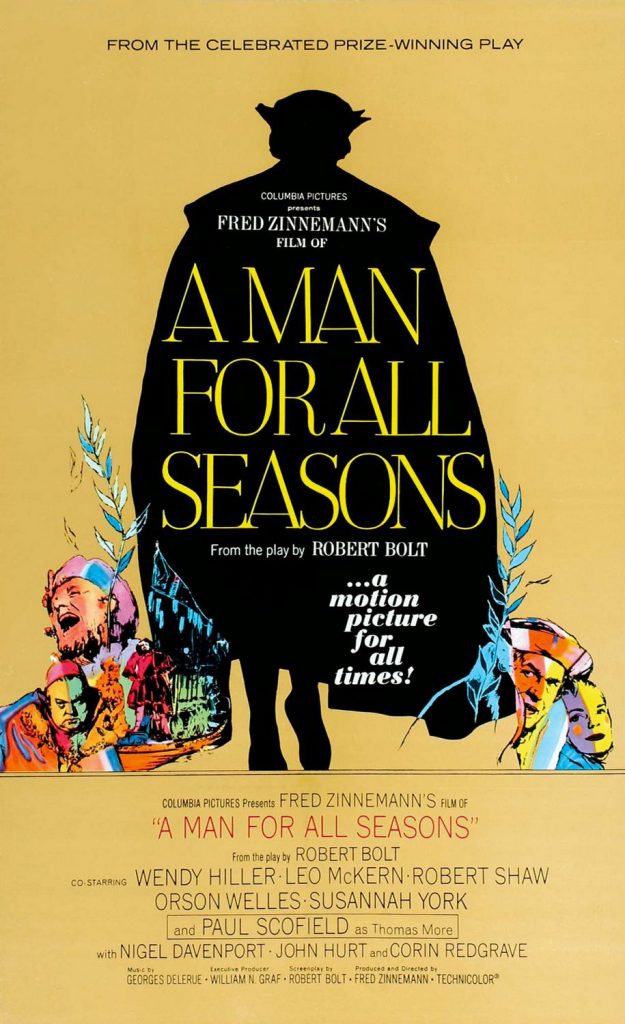

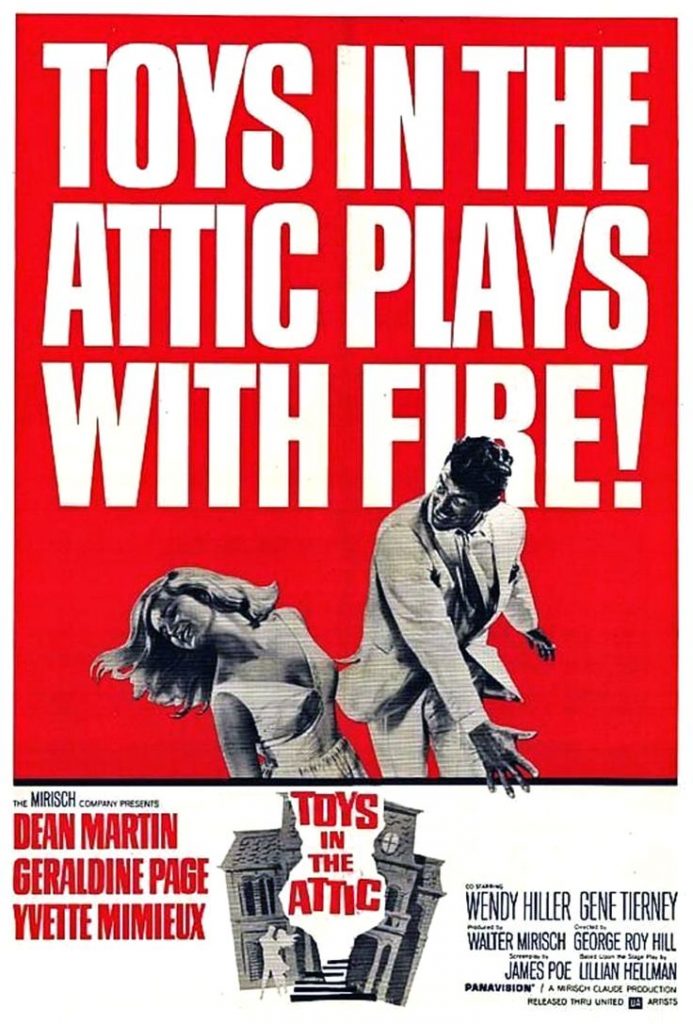

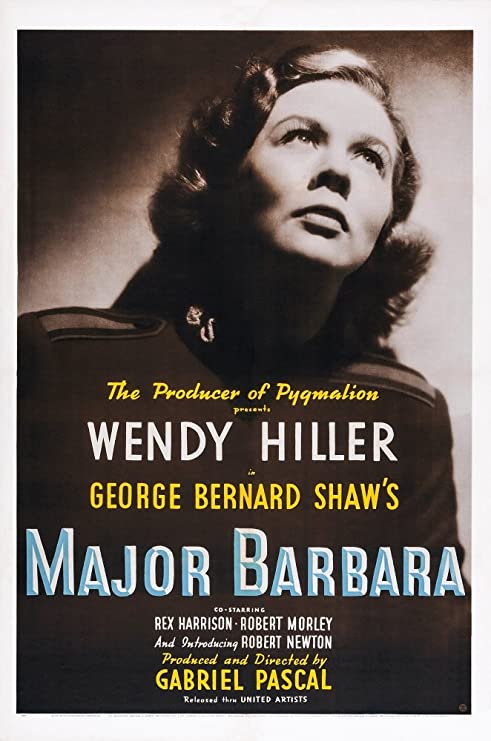

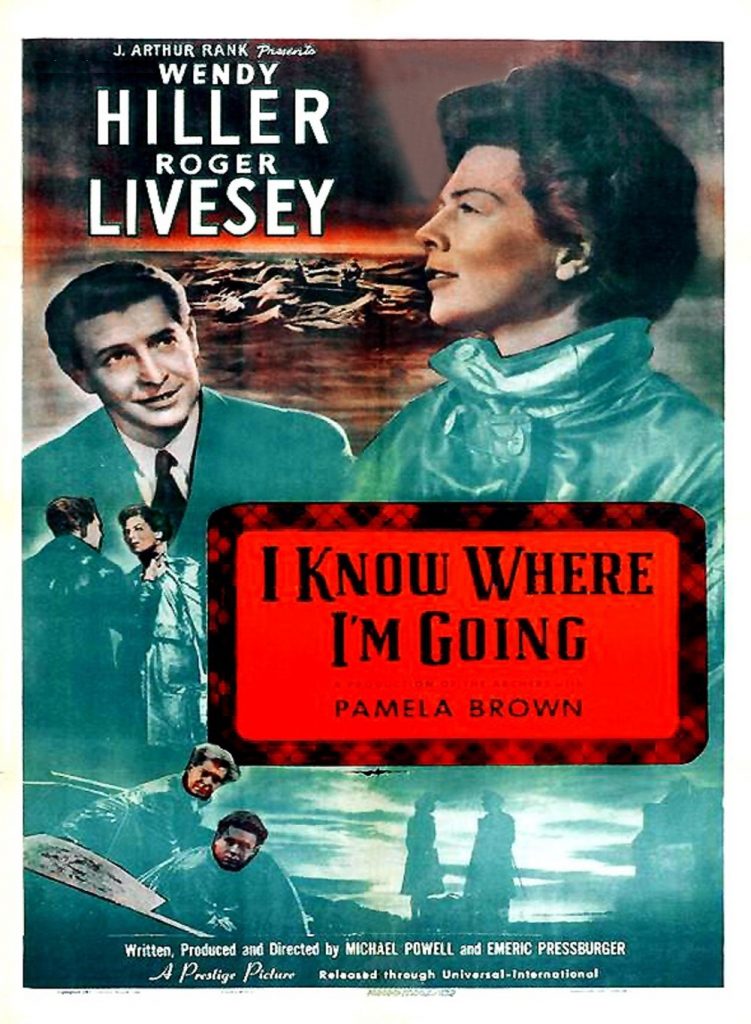

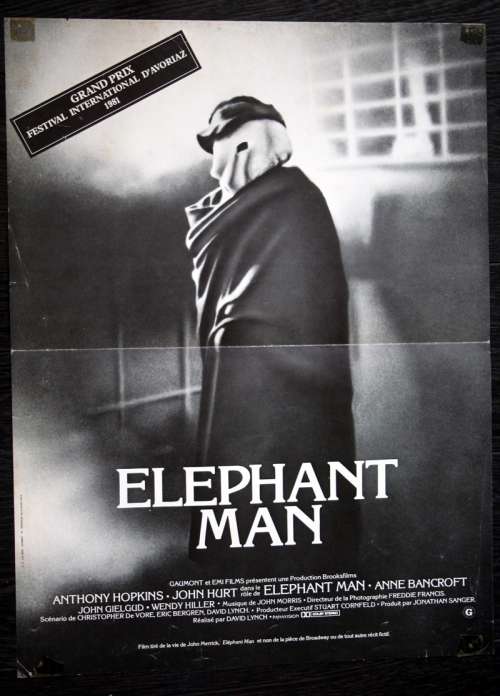

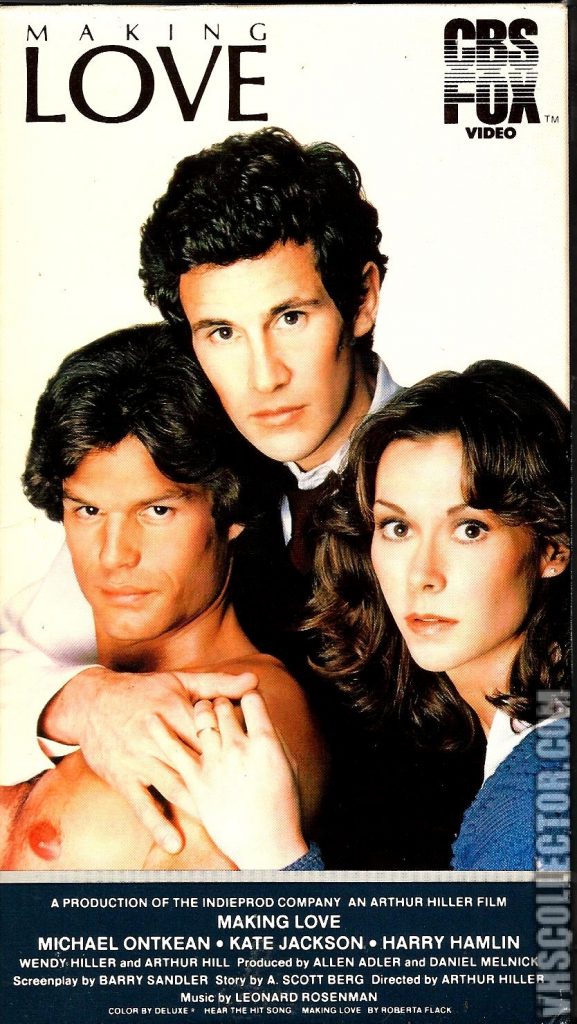

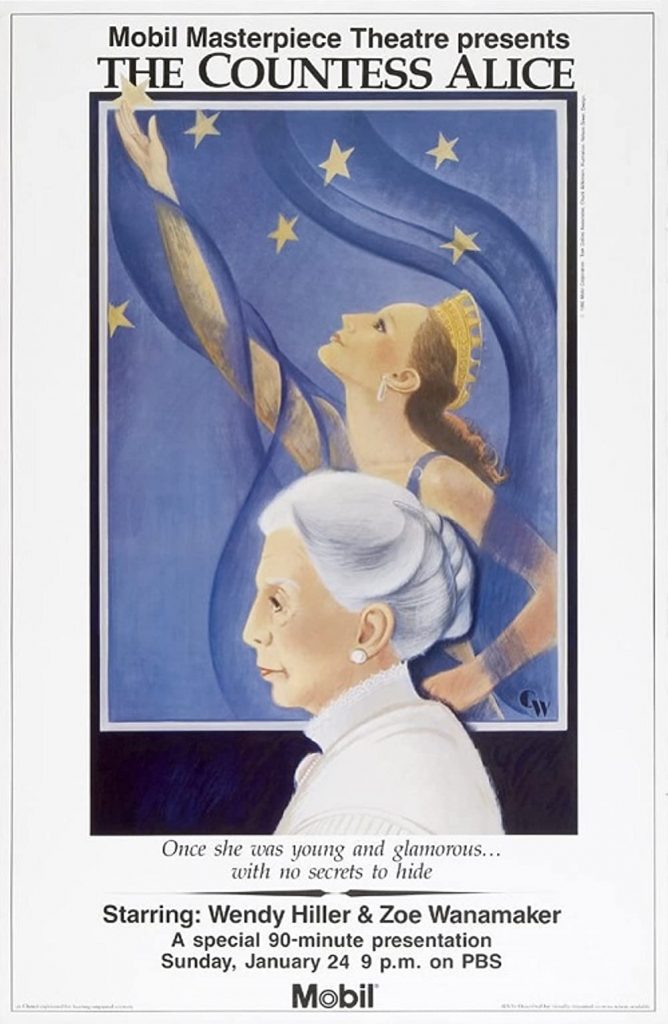

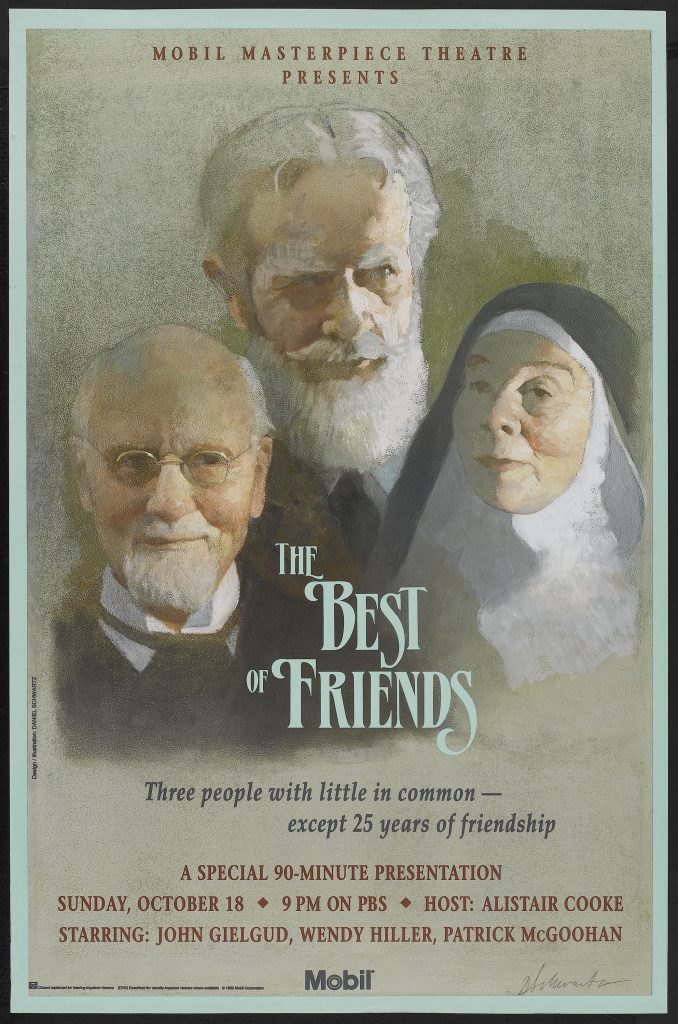

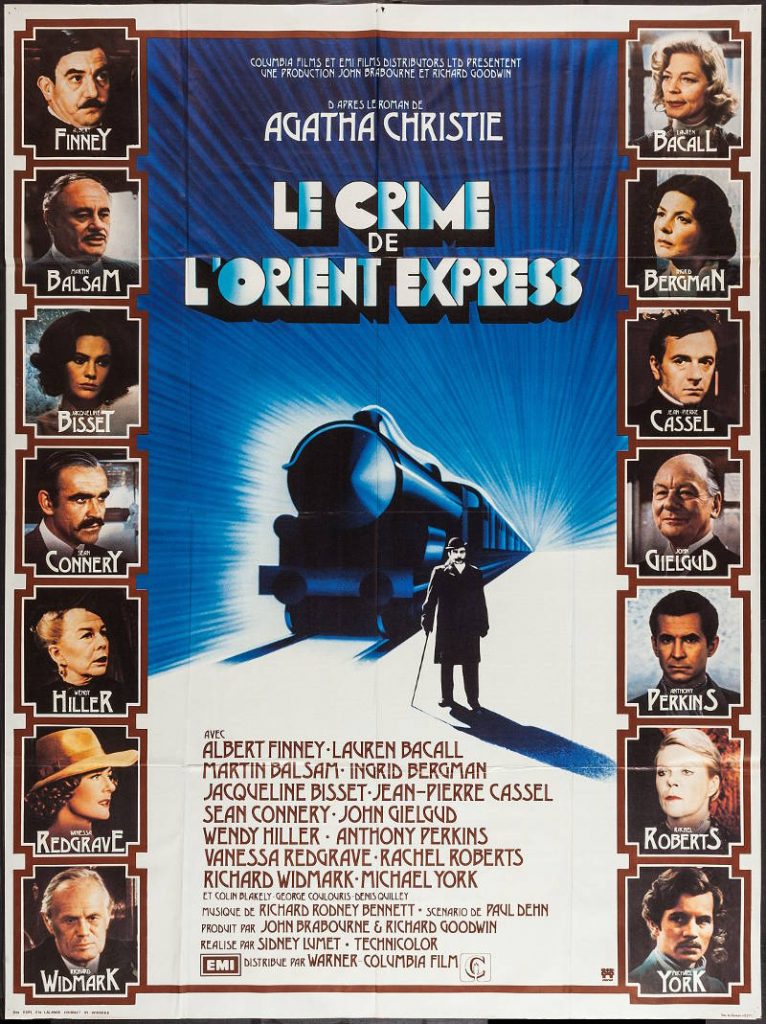

Her best films, after Pygmalion, were Shaw’s Major Barbara (1941), I Know Where I’m Going (1945), Separate Tables (1958, for which she won an Oscar as the manager), Sons And Lovers (1960), A Man For All Seasons (1966) and Murder On The Orient Express (1974). She seemed as true on screen as on the stage, and there might have been more; but the stage stole her heart.

Wendy Hiller was appointed OBE in 1971 and created dame in 1975. Her husband died in 1993, and she is survived by a son and a daughter.

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

· Wendy Hiller, actor, born August 15 1912; died May 14 2003