Constance Smith “Irish Post” article.

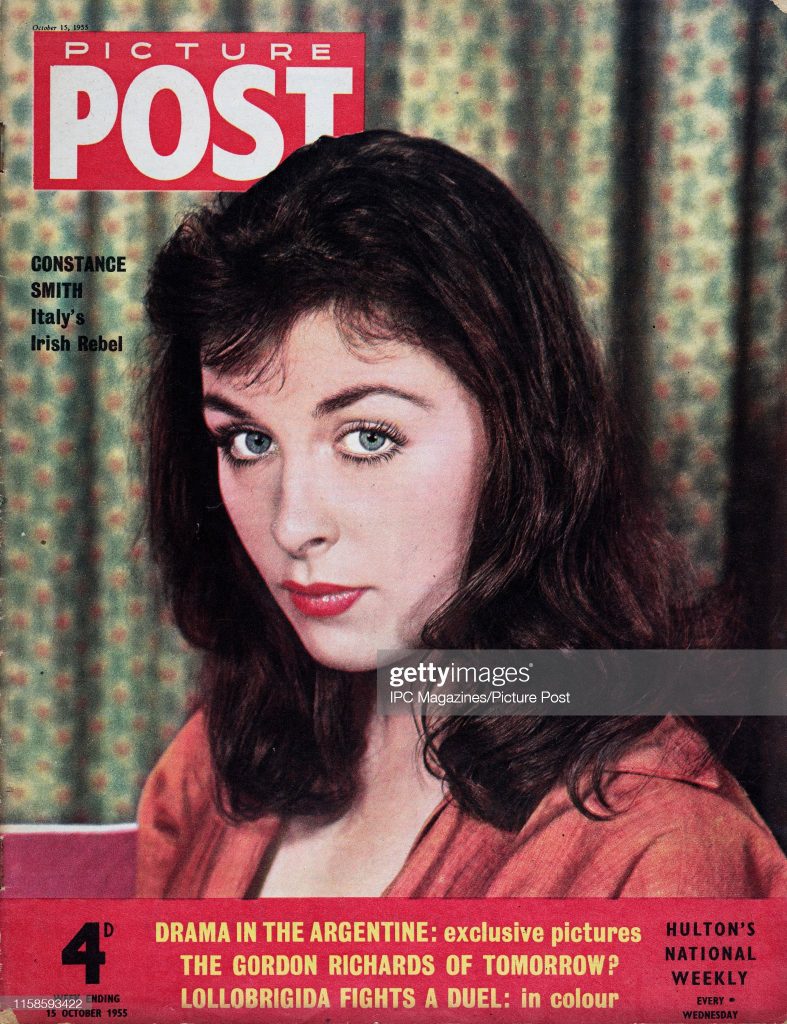

Dubbed the ‘new Grace Kelly’, Irish actress Constance Smith was a big-screen starlet before drink and drug addiction led her to an impoverished death 10 years ago. As a fusion of dark beauty queen, femme fatale and flawed heroine, Smith was a film performer whose own life might have served the plot of a lush fifties melodrama, say one directed by Douglas Sirk.

Constance who?

People might wonder if they’ve either forgotten her name or never even heard of her, but in the 1950s she was a promising Hollywood newcomer to the Fox studio and presented an award at the 1952 Oscars, a responsibility that carries the peer respect of the film industry. She was born impoverished in Limerick city, in 1928 and last month marked 10 years since her death, in London, almost penniless and almost completely forgotten.

Despite this, Smith’s lifetime experiences almost reflected the arc traced by any memorable movie character or story protagonist. Talk about ups and downs. Smith followed a path from poverty to celebrity to notoriety to obscurity. As a young actress she was, for a short period, the special muse of Darryl F. Zanuck, invited and initially welcomed into the rarefied air of Hollywood.

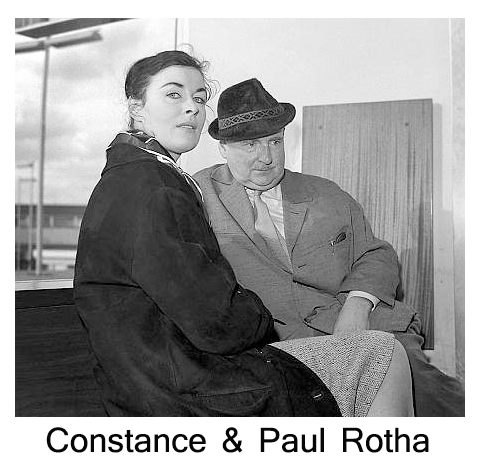

As an older woman she was, for a short period, the special guest of Her Majesty, imprisoned for knifing her husband in a drunken domestic dispute. The husband, maverick documentary maker Paul Rotha, escorted her to the prison gates and met her there on her release. Smith and Rotha then remained a couple, on and off, for decades until his death.

But Smith’s dusky sexual allure always had a bewitching effect on her men. She had three husbands, including one who was the son to an Italian Fascist senator, who regarded his daughter-in-law as a shoeless Irish peasant. More significantly, she married Bryan Forbes, the challenging British film-maker who madeWhistle Down the Wind (1961) and The L-Shaped Room (1962).

Forbes witnessed first-hand how the studio system first supported then crushed Smith in her Hollywood career, and it’s tempting to imagine that some of what he saw influenced his dystopian sci-fi drama The Stepford Wives (1975).

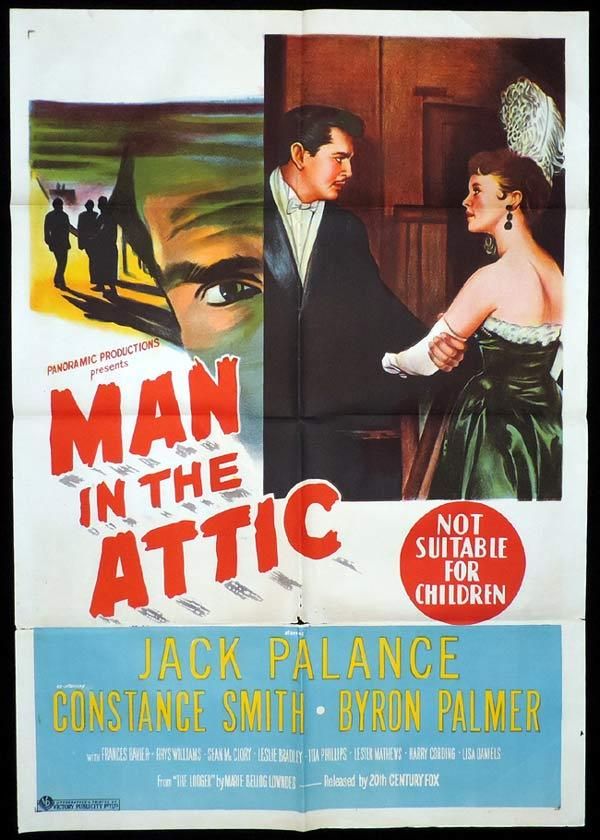

Having been first cosseted by Zanuck and the Fox studio, Smith was summarily dumped. Fox had forced her into an abortion and tried, unsuccessfully, to make her change her name. Forbes later wrote: “When the blow fell… the Hollywood system allowed of no mercy. She was reduced to the status of a Hindu road sweeper.” The difficulty for Smith was making her mark in American cinema when Irish performers were thought suited to mildly-exotic, fiery or fantastical roles, rather than the darker, sultry ones that fitted her looks. Yet with Jack Palance in Man in the Attic (1951) and in Impulse (1957), she showed signature noir-like qualities. Palance once called her the “Dublin Dietrich”

. Elsewhere she was dubbed “an intelligent man’s Elizabeth Taylor” and she was frequently termed the new Maureen O’Hara or Grace Kelly. Smith originally earned her chance in movies by winning a Hedy Lamarr look-a-like competition and perhaps her acting development was hindered by constant comparisons to established figures. Later, when she fell out of the limelight and into drink and drugs addiction,

she worked as a cleaner and workmates remarked that she looked familiar but they couldn’t place her. “It seems regrettable that Constance Smith should have been so completely forgotten given that she was once, if briefly, a Hollywood star,” observes Ruth Barton, film scholar and author of Acting Irish in Hollywood.

It’s to Barton’s credit that she does the proper work of an historian, which is to retrieve from the past those details that make us rethink what we believe we know. How few of us knew there was an Irish film figure of such intrigue? We might nowadays recall Smith’s name with the likes of O’Sullivan, O’Hara and Kelly, had her fortunes not turned so sour. In Emeralds in Tinseltown, Steve Brennan and Bernadette O’Neil’s glossy span of the Irish influence upon Hollywood, the authors relegate Smith to the also-rans section. Barton, meanwhile, rescues her from the dustbin of history.

But while we should remember Constance Smith, we should not pity her. While perhaps we should mourn her as a faded talent, we should not patronise her as a tragic victim. Instead, she was a survivor, even an inspiring one, who found some success in a most demanding field, absorbing the blows as best she could when the sinister side of that success turned upon her.

Perhaps Hollywood was over-subscribed with dark-haired beauties in the forties and fifties, when Dorothy Lamour, Jane Russell, Gene Tierney and Ava Gardner literally dominated the scene.

Certainly we should not see Constance Smith as tragic merely because she lost her fame, a phenomenon that’s often a hollow reed. What’s sad is that she never fully realised her potential as a drama performer, even while her own life was so dramatic.

She was not quite right for those flamboyant, flame-haired roles played by Maureen O’Hara or the pristine, ice-queen personas of Grace Kelly. She was more a Scarlett O’Hara type, who rolled with the punches as her world crumbled around her, and lived by the mantra that “tomorrow is another day.”

For Irish Post article on Constance Smith, please click here.

Limerick Life article in 2016.

Constance Smith was born in 1928 at 46 Wolfe Tone Street, just a short walk from Limerick train station. It was to be an auspicious sign for the little girl who would grow to be a celebrated actor; her extraordinary life would transport her from that small terraced house in Limerick to a convent in Dublin, from a Hollywood mansion to an Italian villa and finally, from Holloway Prison to a sad, troubled end in a London hostel.

While most film fans are familiar with Irish movie stars of the past such as Maureen O’Hara, Peter O’Toole and Richard Harris, few people, even in Limerick, are aware of Constance Smith and her short-lived Hollywood career. Ruth Barton is an academic and author of Acting Irish in Hollywood: from Fitzgerald to Farrell in which she dedicates a chapter to Constance Smith, to retrieve her and other lost stars “from historical oblivion”. Much of what you’ll read below emanates from her painstaking research.

Constance Smith was born to Mary Biggane, a Limerick native, and Sylvester Smith, a former British soldier and veteran of World War One. Initially, her father, a Dubliner, worked as a labourer at the Ardnacrusha plant, but when the project was completed in 1929, he moved his family back to the capital. There they settled in a one-room tenement in Mount Pleasant Buildings, Ranelagh, described by the Irish Times as a ghetto, “used by the Corporation as dumping grounds for problem families.”

Life was arduous and often dangerous in the slums of Mount Pleasant. Communal toilets were poorly maintained, overflowing rubbish bins were infested with rats, and cold, lung-choking air seeped through the damp brick walls; it was little wonder that Irish infant mortality rates were among the highest in Europe at the time. Indeed, many of Constance’s ten siblings did not make it to adulthood.

The only respite from the grinding poverty was a sort of ad-hoc community theatre which developed among the residents. Groups gathered together in the evenings, sang songs from penny-sheets, performed skits for one another and, if the owner was feeling generous, listened through open windows to the street’s one wireless radio. It was in this way that Constance likely received her first training in the dramatic arts.

Constance’s father died when she fifteen. Unable to support her surviving children on her own, Mary Biggane sent her daughter to St. Louis Convent School in Rathmines. The headstrong teenager escaped early, however, taking casual jobs as a shop girl and housemaid to support herself.

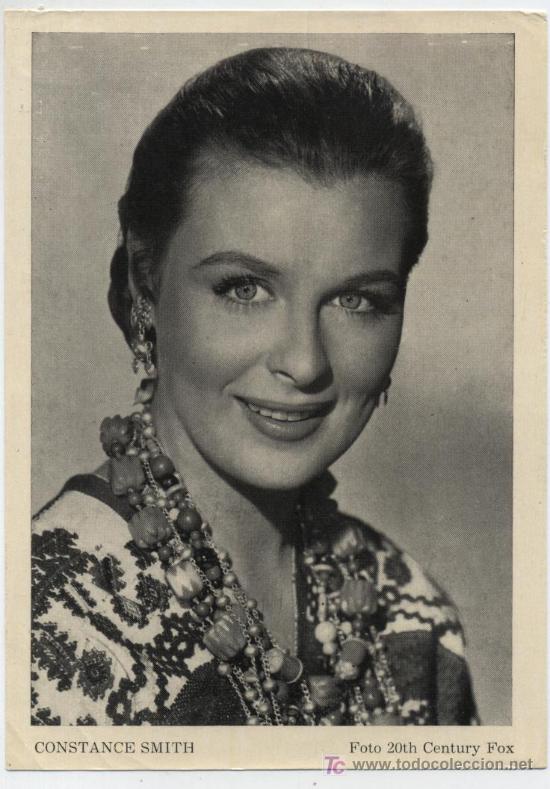

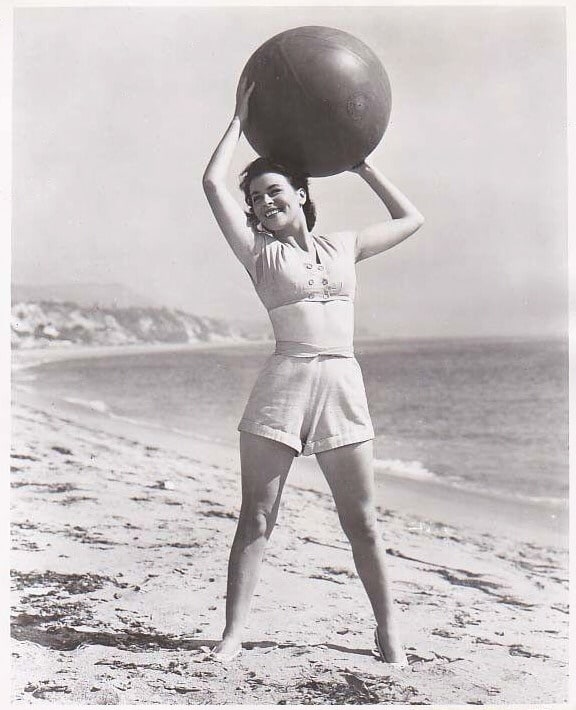

It was this latter position that set her on the path to stardom. In 1945 she was placed in a ‘big house’ in Rathmines and the family for whom she worked encouraged her to enter a ‘Film Star Doubles’ contest in The Screen, an Irish film-industry publication. She went on to take first place – dressed as Hedy Lamarr in a borrowed dress – at the magazine’s ball, attended by local actors, theatre producers and crucially, international talent scouts.

She was invited to screen-test at Denham Studios in England by Rank Organisation, who saw potential in the beautiful, sultry-eyed young woman. In 1946 she signed a seven year contract with the group and was put through the rigours of their ‘charm school’ at Highbury, in London. This was essentially a factory for starlets, in which young ingénues were taught elocution, breathing exercises and comportment, along with more traditional drama lessons and script rehearsals. Objecting, perhaps, to spending her time balancing books on her head, Constance lasted only a few years in the school. She resisted attempts to change her name (‘Tamara Hickey’ was suggested, straddling the line between thrillingly exotic and reassuringly local) and steadfastly clung to her Irish accent, a refusal which eventually led to her dismissal from Rank Organisation. Her private life was faring better, however, as she became engaged to British film producer John Boulting.

Once again, life was to take a fortuitous turn for Constance. She won a small part playing an Irish maid in the film The Mudlockin 1950, receiving £20 per day for five weeks. In four short years, she had come a long way from a position as a housemaid for £2 a week. She was spotted in this film by Darryl Zanuck, a legendary Hollywood mogul and co-founder of the movie studio 20th Century Fox. He took a close interest in her – whether his intentions were purely professional is unknown – and championed her as an undiscovered star. She was granted a seven year contract with the studio and placed opposite Tyrone Power in The House in the Square, to begin shooting in London in 1950. The movie was a big, all-star production, and the media fanfare began early.

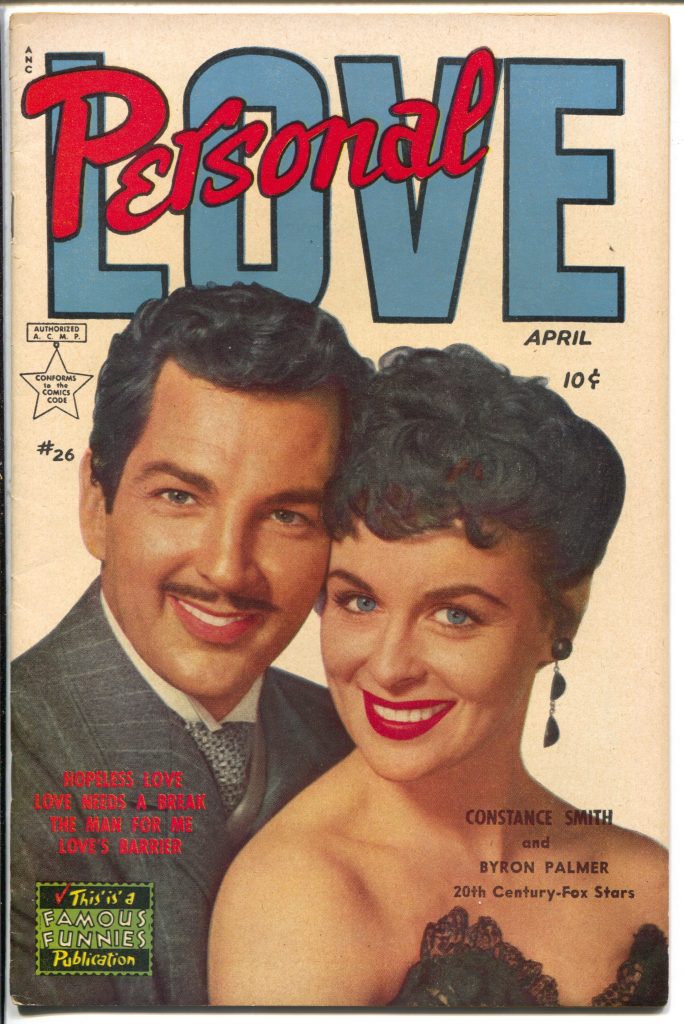

However, the young, untrained actor struggled to perform alongside experienced heavy-weights such as Power. Midway through filming she found herself unceremoniously dumped from the picture, losing all the publicity and career momentum it had brought. The studio cited illness, and replaced her with Ann Blyth, reshooting all her scenes at a rumoured cost of £100,000. Constance was devastated, but found comfort on the shoulder of a successful British actor named Bryan Forbes (best known for directing The Stepford Wives, 1975), whom she married in 1951.

Back in Hollywood, she found herself packaged and presented as a beautiful but feisty Irish ‘colleen’, the new Maureen O’Sullivan (remembered as Jane in the Tarzan movies). Whether acting on her own volition or that of the studio’s, Constance had an abortion just before Christmas of 1951. 20th Century Fox paid the $3,000 fee.

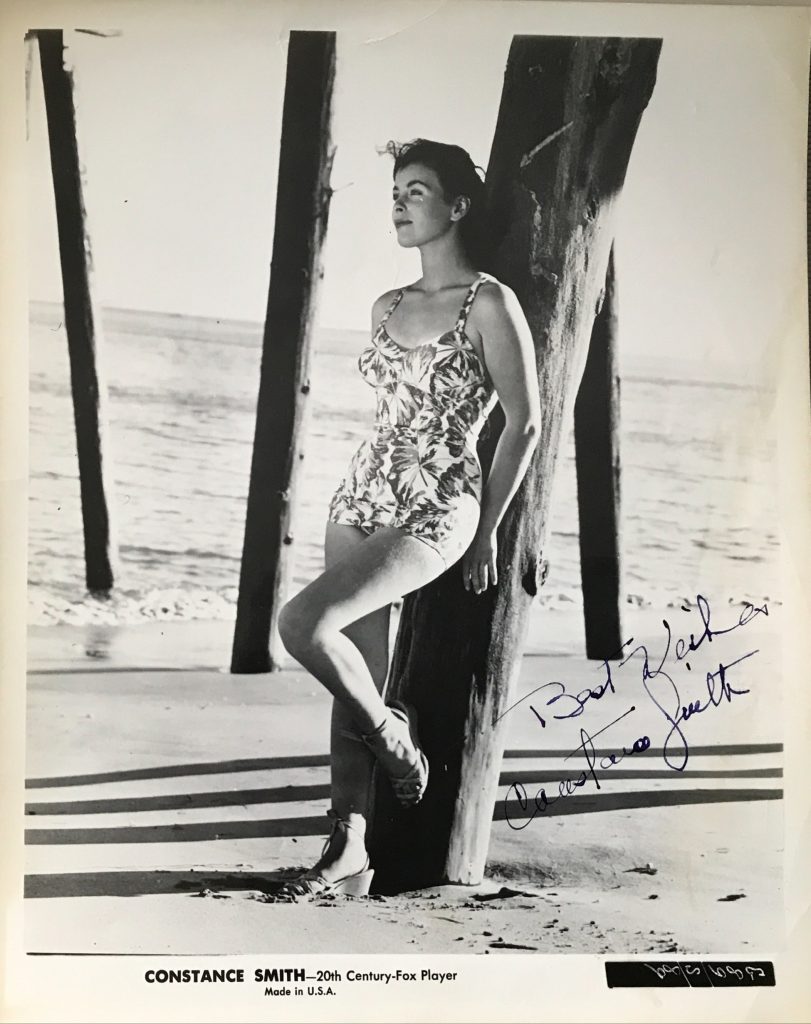

Her marriage failed soon after, but her career was steady. She shot a number of films, receiving praise for her sensuous, noirish performances from fellow actors (Jack Palance referred to her as the ‘Dublin Dietrich’) and the occasional breathless review from critics. One paper, in the parlance of the time, noted that she possessed “a pair of the nicest gams to ever leave the Old Sod.” In 1952 she was invited to present a trophy at the Annual Academy Awards.

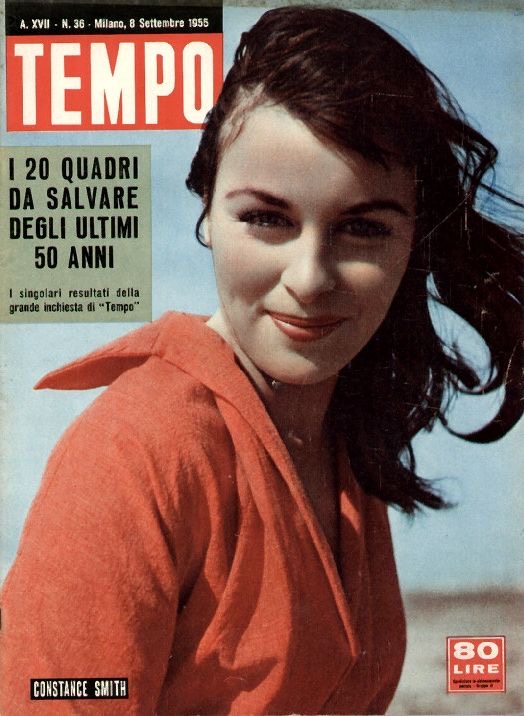

Having parted company with 20th Century Fox, she signed with Bob Goldstein in 1954, who promptly put her to work filming the thriller Tiger in the Tail, in London. Frustrated by the lack of first-rate roles, she left for Italy in 1955, casting off her rebel charm to reinvent herself as the descendent of Irish aristocrats. There, she met an Italian photographer named Araldo di Crollolanza and married him a year later, at the age of twenty-eight. His father – a Fascist senator who had served under Mussolini – reportedly disinherited his son upon learning of the union, even going so far as to refer to his new daughter-in-law as a ‘barefoot Irish peasant’. She made four films in Italy, but her career began to falter and she took an overdose of sleeping tablets in 1958. Her husband left her and she returned to England.

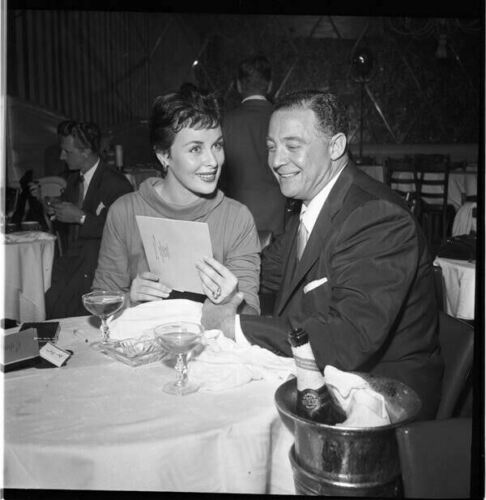

In 1959 she met Paul Rotha, a married man of fifty-two and a much-celebrated filmmaker and writer. They couldn’t have made a more different pair; a neat, precise and serious Englishman, who fell in love with a tempestuous, free-spirited and creative Irishwoman. Theirs was a predictably fiery relationship, only made more difficult by their mutual propensity for hard drinking. They shared similar socialist-leaning political beliefs though, both avowedly anti-fascist and anti-imperialist. Constance was no longer acting, but she remained well-known in film-industry circles in London. She was, one contemporary noted, ‘an intelligent man’s Elizabeth Taylor’.

Together, she and Rotha travelled to Germany to research a documentary on Adolf Hitler’s life. There, they met close aides to the dictator, as well as survivors of the concentration camps. She was said to be greatly affected by this experience.

In 1961, the couple visited Constance’s birthplace, calling to the house on Wolfe Tone Street in Limerick. They were greeted with much fanfare by Constance’s former neighbours, many of whom clamoured for photographs and autographs. The purpose of the visit, Rotha told reporters, was for research – he intended to write a book on his Constance’s life, entitled ‘A Weed in the Ground’, a project which failed to materialise.

Back in London, the couple’s relationship was growing increasingly turbulent. Their fights were frequent and quite often physical; after one altercation Rotha’s face was so badly bruised that he had to postpone an overseas trip. In 1961 a particularly nasty row very nearly turned fatal when Constance stabbed Rotha, leaving him lying on the floor of his flat, bleeding heavily. She also tried to slash her own wrists.

Rotha recovered from his extensive injuries, and supported his lover during her trial in 1962. In court, Constance’s defence team made much of her poverty-stricken childhood, her failed movie career and her traumatic experience in post-war Germany. She was given a three month sentence, and upon her release from Holloway Prison she was met at the gates by Rotha.

They were reunited, but the period was not a happy one. They sold their story to a tabloid newspaper, which salaciously reported their living together out of wedlock. Constance’s mental health deteriorated and she spent time in psychiatric care. In 1968, she stabbed Rotha again, this time sinking a steak knife into his back. The court placed a restraining order against Constance but again, Rotha stood by her. They eventually married in 1974, some fifteen years since they had first met. It was to be her third and final marriage.

Time in prison hadn’t quietened her demons however, and Constance was back in Holloway Prison in 1975, for yet another stabbing offence. While she made a half-hearted attempt to leave Rotha, she quickly returned to him, and together, they descended into a spiral of alcohol abuse, poverty and physical violence. The once highly-respected author and filmmaker took to charging visitors £50 for interviews, along with a bottle of Scotch for himself and Vodka for his wife.

By 1978 they were effectively homeless, and Constance had taken a job as a hospital cleaner. Around this time, after almost twenty years together, the couple broke up. Rotha wrote at the time, “my wild Irish wife has finally left me, gone God knows where.”

Constance Smith’s final act was slow to play out, despite the fiercely harsh circumstances of the latter years of her life. She lived for a while in destitution, losing toes to frostbite and drinking on the streets of Soho. She spent the next two decades on a miserable carousel of psychiatric hospitals, hostels and homelessness, before eventually dying of natural causes in Islington in 2003.

She lived through a fascinating era of modern history; born in the infancy of the Irish Free State, she found herself living in a Blitz-ravaged London a year after VE Day. She went on to work with black-listed artists during the infamous Red Scare in Hollywood and married the son of a Fascist Senator in Italy. She worked with one of Britain’s best-known documentary makers and interviewed survivors of the Holocaust. The life of Constance Smith is more interesting, more dramatic and more poignant than any Hollywood blockbuster. Perhaps it was just too much, too soon for the girl from Wolfe Tone Street.

In her book, Ruth Barton writes perhaps the most sympathetic and understanding epitaph for the Irish actor who flew too close to the sun. Constance, she writes, was, like many almost-stars of the period, “overwhelmed by an unforgiving system for which their background left them unprepared.”

Today, Constance Smith is fondly remembered by those neighbours for whom she signed autographs in 1960, and her memory is maintained by Ms Barton and her fellow academics, by interest groups such as the Limerick Film Archive and by artists like Kate Hennessey.

If you happen to pass Ms Hennessey’s mural on Clontarf Place, stop for a moment and cast your eyes upwards. Among the many Limerick women celebrated there, you’ll find the dark-haired, smiling face of Constance Smith, just a stone’s throw from her family home.

Dictionary of Irish biography:

Constance Mary (1928–2003), actor, was born in January or February 1928 in Limerick. Her father, a Dublin native who had served in the British army during the first world war, was working on construction of the Ardnacrusha power station; her mother Mary was from Limerick. On completion of the station in 1929 the family moved to Dublin; her father died soon thereafter. One of seven or eight children, Constance was reared in extreme poverty in a one‐room flat in Mount Pleasant Buildings, Ranelagh, and was educated at St Louis convent primary school, Rathmines. She worked in a local chip shop, an O’Connell Street ice‐cream parlour, and as a domestic servant. A blue‐eyed brunette, strikingly beautiful from a young age, in January 1946 she won a special prize in the Dublin film star doubles contest (as Hedy Lamarr), on foot of which she was screen-tested by the Rank Organisation, and signed to a seven‐year contract. Moving to London, she was groomed in etiquette, poise, and acting technique in the Rank acting school (the so‐called ‘charm school’). She first appeared on screen in an uncredited, but eye‐catching role, as a cabaret singer in the underworld classic Brighton rock (1947); she was engaged for a time to the film’s director, John Boulting. Though never cast in a Rank film, she appeared in several independent productions, including Room to let (1950), as the daughter of a landlady whose mysterious new tenant turns out to be Jack the Ripper. About 1950 she was sacked by Rank, supposedly for objecting to criticism of her Irish accent; she also resisted the studio’s efforts to change her name.

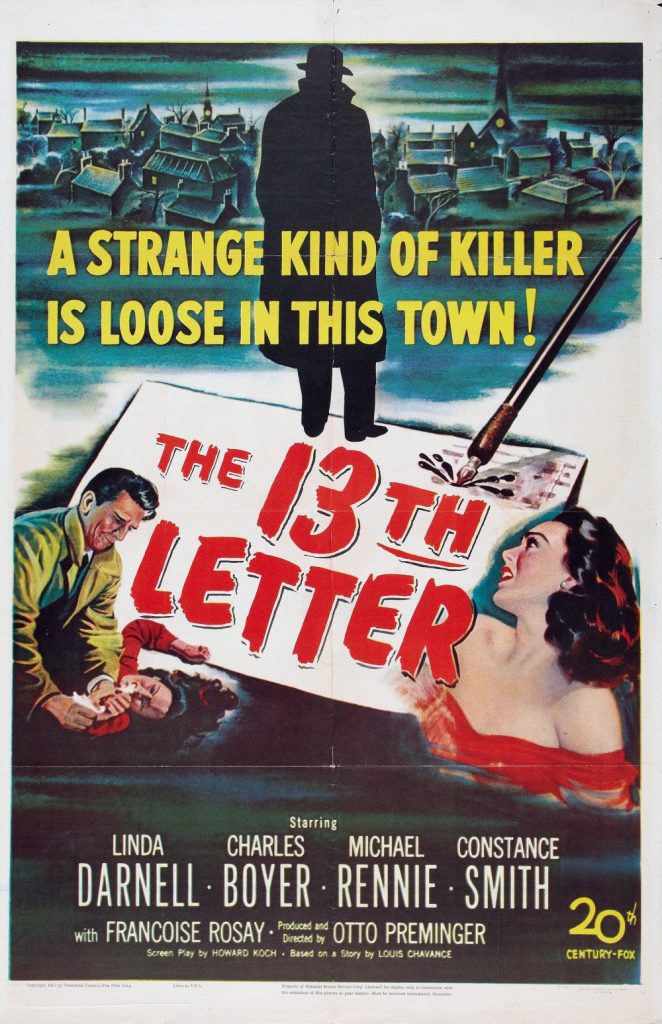

Her vivacious performance as an Irish maid in The mudlark (1950) attracted the attention of Darryl Zanuck, head of production at Twentieth Century Fox, who signed her to a seven‐year contract, and vigorously promoted her as his Emerald Isle discovery. En route to Hollywood, she worked on location in Canada in Otto Preminger’s impressive film noir The 13th letter (1951), as the wife of a hospital doctor (played by Charles Boyer) in a small Québec village, who is suspected, on the basis of poison‐pen letters, of an adulterous involvement with a newly arrived English doctor (played by Michael Rennie). Cast in a coveted role opposite Tyrone Power in The house in the square (1951), she returned to London for filming, but was soon embroiled in studio politics, and uncomfortable in a part too demanding for her experience and skills. After six weeks on set she was abruptly dropped, her role was recast, and her scenes re‐shot.

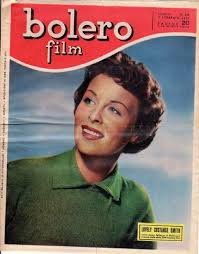

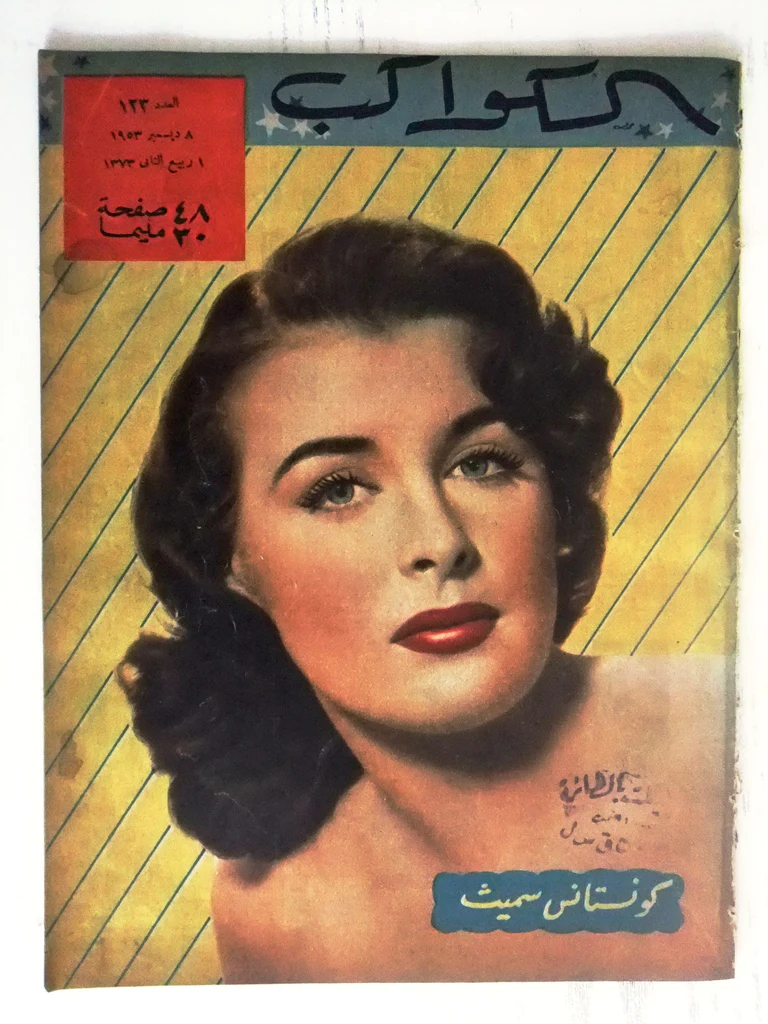

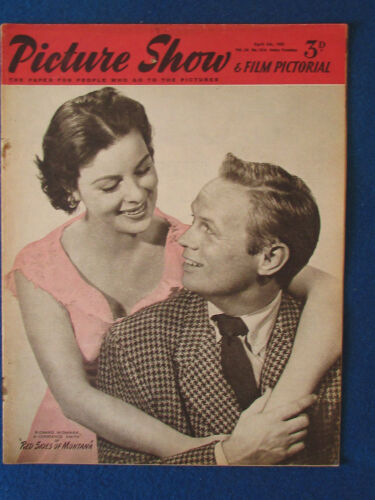

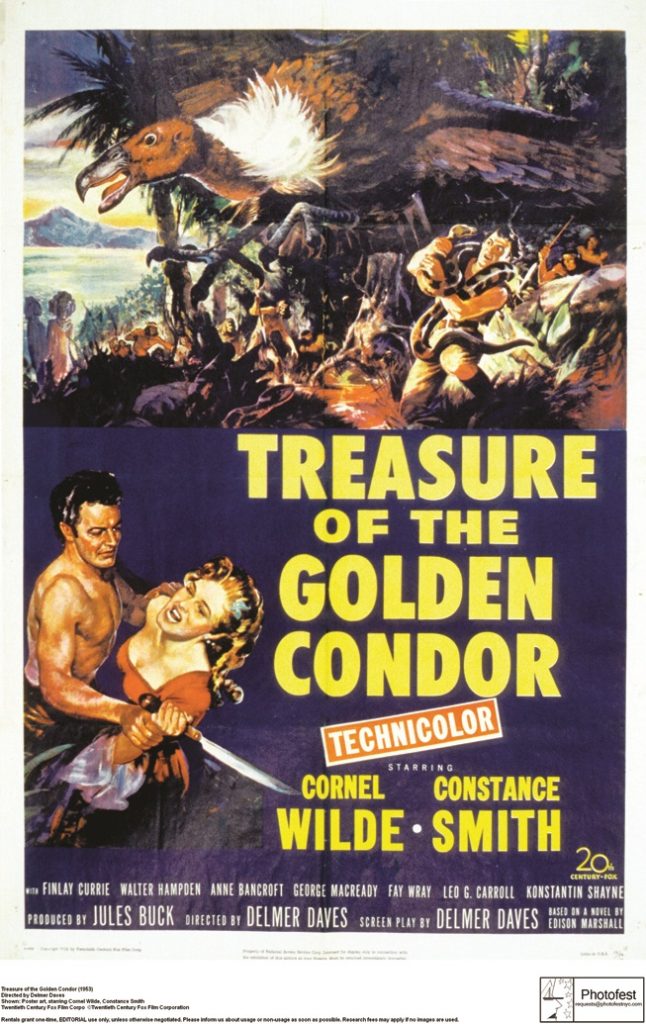

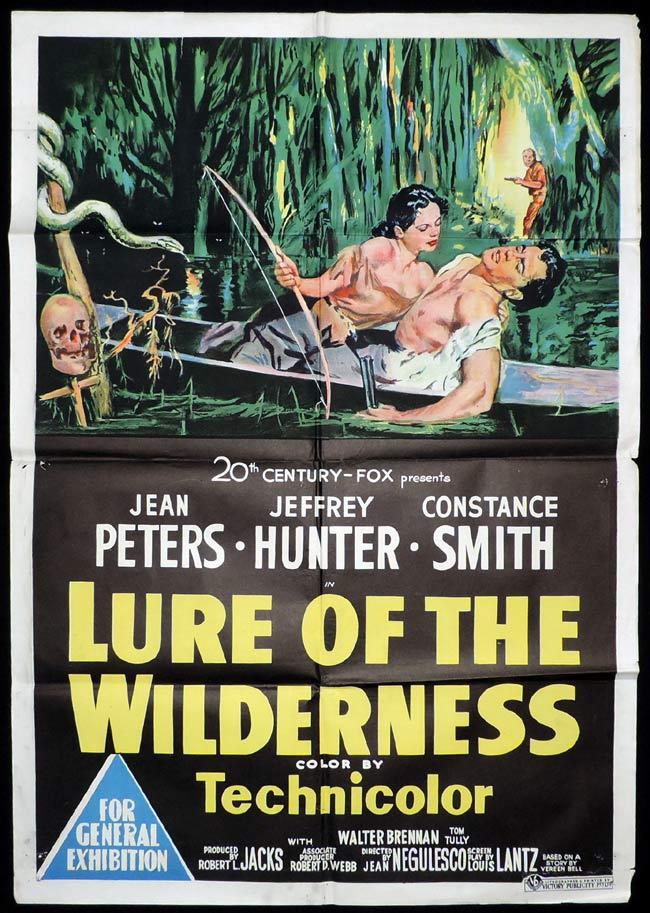

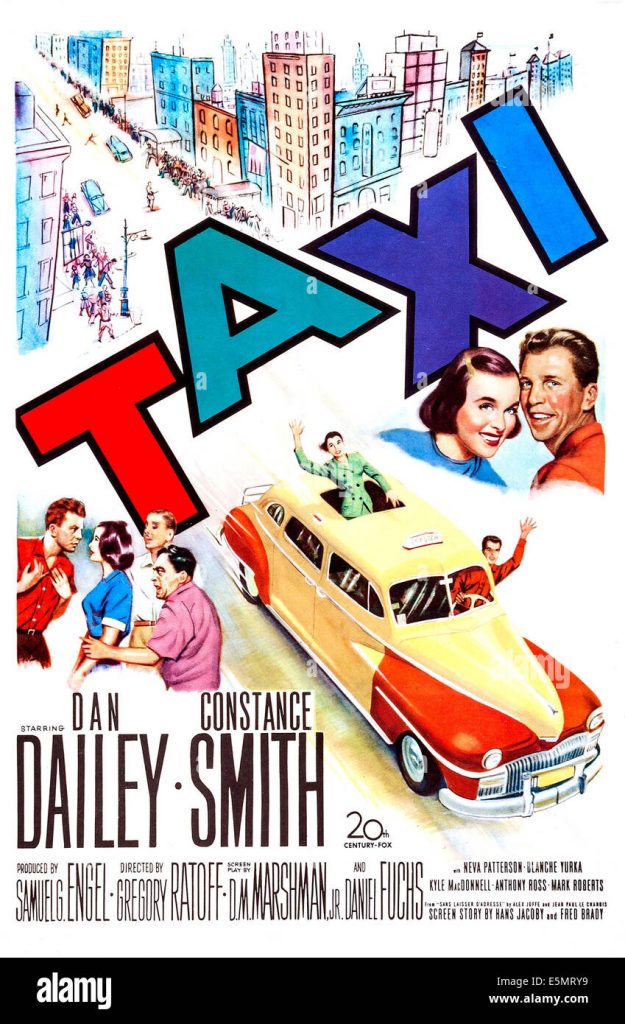

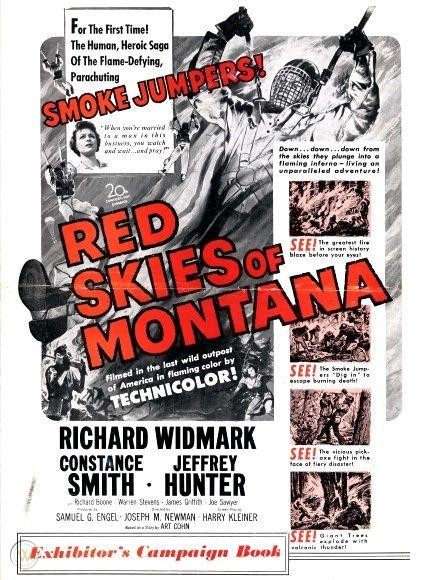

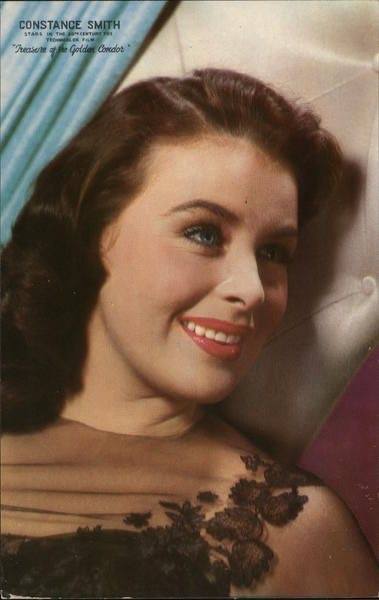

Despite this setback, for the next few years she was cast by Fox in starring roles opposite some of the studio’s leading male actors. Nonetheless, her own star status seems to have been generated more by intensive studio publicity than by the quality or success of her movies. She appeared on the cover of Picturegoer, the leading British film magazine of the period (March 1951), and was a presenter at the 1952 Academy awards ceremony. Her image was that of a spirited, innately rebellious individualist, unafraid to defy studio manipulation – qualities attributed by the entertainment press to her Irish ethnicity. One industry colleague remembered her as ‘the intelligent man’s Elizabeth Taylor’ (Barton, 117). Her credits included Red skies of Montana(1952), as the wife of the chief of a crew of forest‐fire‐fighters, played by Richard Widmark; Lure of the wilderness (1952), with Jeffrey Hunter; Treasure of the golden condor (1953), opposite Cornel Wilde; and Taxi (1953), as a newly landed Irishwoman assisted by a New York cabdriver in searching for the American husband who abandoned her. She gave a lively and rounded performance in Man in the attic (1953), another take on the Ripper legend, as the showgirl niece of the murderer’s landlord and his wife, a role that highlighted her singing and dancing talents. Her co‐star, Jack Palance, suggested that she be billed ‘the Dublin Dietrich’, and some reviewers detected her potential as a live nightclub performer.

By 1954 she had left Fox; it is possible that the mental instability and problems with alcohol that would later become obvious were already afflicting her career. She appeared with Richard Conte in an intriguing noir, The big tip off (1955), and made two films in London: Tiger by the tail (1955), as the reliable English secretary of an American journalist pursued by gangsters, and Impulse(1955), as a seductive femme fatale. Her star waning, in the latter 1950s she made five films in Italy, where she was promoted as a brunette Grace Kelly. Giovanni dalle bande nere (The violent patriot) (1956), a costume swashbuckler, played the USA drive‐in circuit. Her last film was La congiura dei Borgia (1959).

Smith married firstly, after a whirlwind romance in London (1951), Bryan Forbes , an aspiring British actor, and later a successful screenwriter, director, novelist, and memoirist. Though he followed her to Hollywood, the marriage had broken by the end of the year, but not before Smith had succumbed to studio pressure and terminated a pregnancy by abortion. The couple divorced in 1955. She married secondly, in Italy (1956), Araldo Crollolanza , the photographer son of a former fascist senator (who opposed the match and disinherited him); the marriage failed by 1959. In the latter year Smith began a relationship with Paul Rotha (1907–84), a leading British documentary filmmaker, film historian, and critic, whose portfolio included two films of Irish interest: No resting place (1951), a fiction film about Irish travellers, and Cradle of genius (1958), a short documentary on the history of the Abbey theatre, which received an Oscar nomination. Smith accompanied Rotha to Germany and Holland during research and filming of a documentary on the life of Adolf Hitler (1961) and a fiction film based on the Dutch wartime resistance (1962). The couple shared leftist, anti‐imperialist political convictions, and a passion for jazz music; Smith painted, and cultivated her interest in the fine arts, while Rotha contemplated writing a book about her life and casting her in films. Ominously, they also shared an addiction to heavy drinking; ferocious rows, often physically violent, became a commonplace. In December 1961 Smith knifed Rotha in the groin and slashed her own wrists in their London flat; pleading guilty to unlawful and malicious wounding, she served three‐months’ imprisonment in Holloway. Defence counsel at her trial referred to two previous suicide attempts, and described her as ‘a poor but beautiful girl who was squeezed into a situation of sophistication and fame when emotionally quite unable to cope with it’ (Times, 12 Jan. 1962).

For the next two decades Smith and Rotha continued their turbulent, on‐again, off‐again relationship, marked by mutual alcoholism, unemployment, increasing financial hardship, episodes of domestic violence, and Smith’s repeated suicide attempts, and admissions to psychiatric hospitals and halfway hostels. During intermittent periods of recovery, she worked as a cleaner and (incredibly) in childcare. After stabbing Rotha in the back in 1968 she received three‐years’ probation; another stabbing in 1975 resulted in a second term of imprisonment. The couple, who married in 1974, did not break up permanently till 1979. In the early 1980s Smith was living destitute and homeless in London; former colleagues would see her, virtually unrecognisable, drinking in Soho Square. The few friends who attempted to retain contact lost track of her in the mid 1980s. She is reported to have died of natural causes 30 June 2003 in Islington, London