Maureen Swanson obituary in “The Guardian” in 2011.

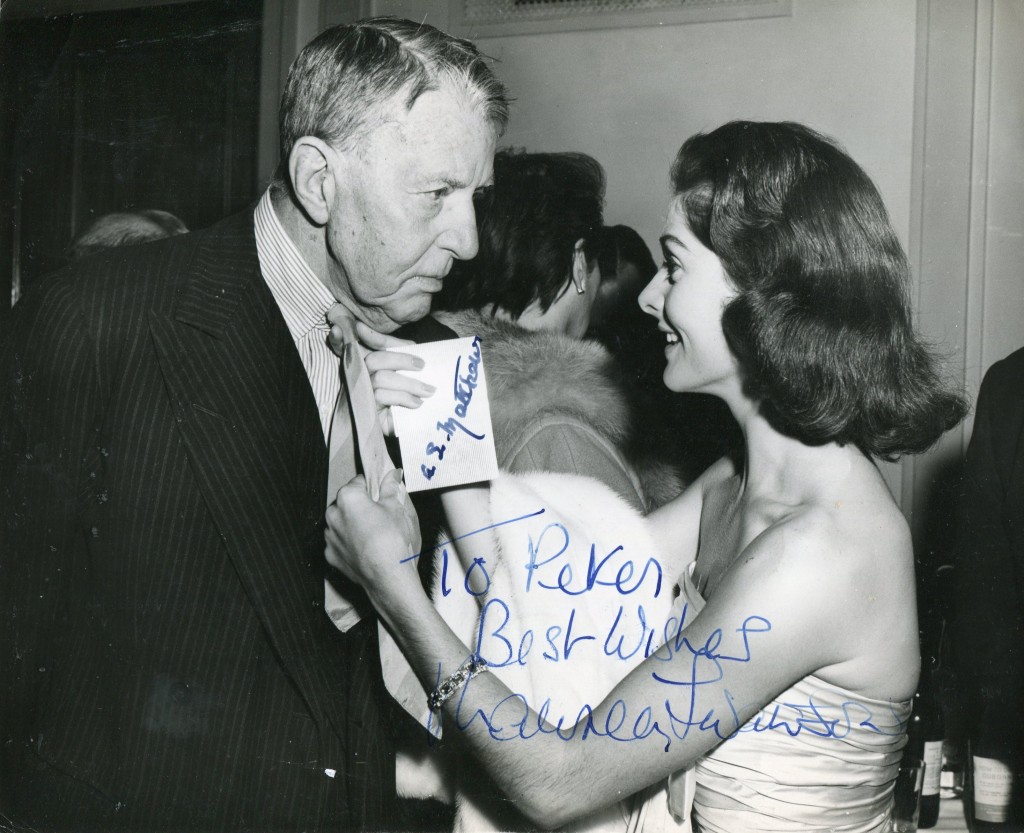

Never having had the chance to justify her initial build-up as “the next Vivien Leigh”, the svelte brunette Maureen Swanson, who has died of cancer aged 78, deserved much better than she was given in the 1950s by the Rank Organisation, to whom she was under contract. Although Swanson was not a graduate of the much-maligned Rank Charm School, she was, to her chagrin, often referred to as a “Rank starlet”, which implied that she was merely on screen in order to look glamorous. But unlike Rank charmers such as Diana Dors, Joan Collins andBelinda Lee, Swanson was not a “naughty” sex symbol, but more of a “good girl”.

She might have gone on to better parts had not her marriage in 1961 to William Ward, Viscount Ednam (later the 4th Earl of Dudley) terminated her acting career for good. The role of Countess of Dudley, and mother of six children, five of them girls, would take up most of her time.

Swanson was born in Glasgow and educated at a convent school there, before going to Paris to study ballet. She soon won a place at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School and then the company itself, for which she had a featured role in The Haunted Ballroom, choreographed by Ninette de Valois. This gave her the chance, aged 19, to take over the important dancing role of Louise in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, in 1951.

Swanson was brought to the attention of the director John Huston, who was making Moulin Rouge (1952) at Shepperton Studios in England. He cast her in the small but significant role of the aristocratic girl who rejects a proposal of marriage from Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (José Ferrer), telling him no woman will ever love him, which prompts him to leave his childhood home in despair to begin a new life as a painter in Paris.

After Moulin Rouge, which earned more money than Lautrec made from all his paintings in his lifetime, Swanson gained even wider international exposure in MGM’s first CinemaScope feature, the spectacular Knights of the Round Table (1953), shot in England. Swanson played the gentle wife of Lancelot (Robert Taylor), who has to contend with the more voluptuous Ava Gardner as Guinevere.Swanson appeared in more modest British fare such as Valley of Song (1953), a charming Romeo and Juliet-type story of a feud over choir singing between two families in a south Wales village. Swanson, with a convincing Welsh accent, had some poignant moments as she pines for her sweetheart (John Fraser).

Her first film under contract to Rank, A Town Like Alice (1956), was her best by far. It covers how a small group of women and children were force-marched through Malaysia by the Japanese during the second world war. In the film, Swanson, the youngest and prettiest of the women, flirts with any available man and even goes off with a Japanese officer.

The Spanish Gardener (1956) tells of a stuffed-shirt British diplomat’s concern about losing the love of his young son, who is closer to his gardener than to him. Swanson plays the girlfriend of Dirk Bogarde, in the title role, slightly mitigating the homosexual subtext, though the fact that both of them play Spaniards with cut-glass English accents is rather disconcerting.

Swanson gets sung to and kissed by Norman Wisdom between all the slapstick in Up in the World (1956), as a maid in a country manor where he is the clueless window cleaner. Her final film was the period adventure story, Robbery Under Arms (1957), set and shot in Australia, where she is effectively furious as a woman scorned. The following year, she made an exquisite Cecily Cardew in the ITV production of The Importance of Being Earnest (1958).

Although Swanson retired from show business completely in 1961 to marry into the English aristocracy, heavily publicised libel cases made sure she was not entirely out of the public eye. First, in 1987, the countess, who had accompanied Princess Michael of Kent on a semi-official visit to the United States, won £5,000 in libel damages from the Literary Review for a review of a book about ladies-in-waiting which, she claimed, had made her out to be a greedy and vulgar woman. In 1989 she won damages from the publishers of a book which suggested she was one of the women procured by Stephen Ward, who was charged with living on the immoral earnings of Christine Keeler after the Profumo scandal. She again accepted damages after Keeler referred to Swanson as being “one of Stephen’s girls” in her 2001 book The Truth at Last. In fact, Swanson had dated him 10 years before the scandal.

Swanson is survived by her husband and children.