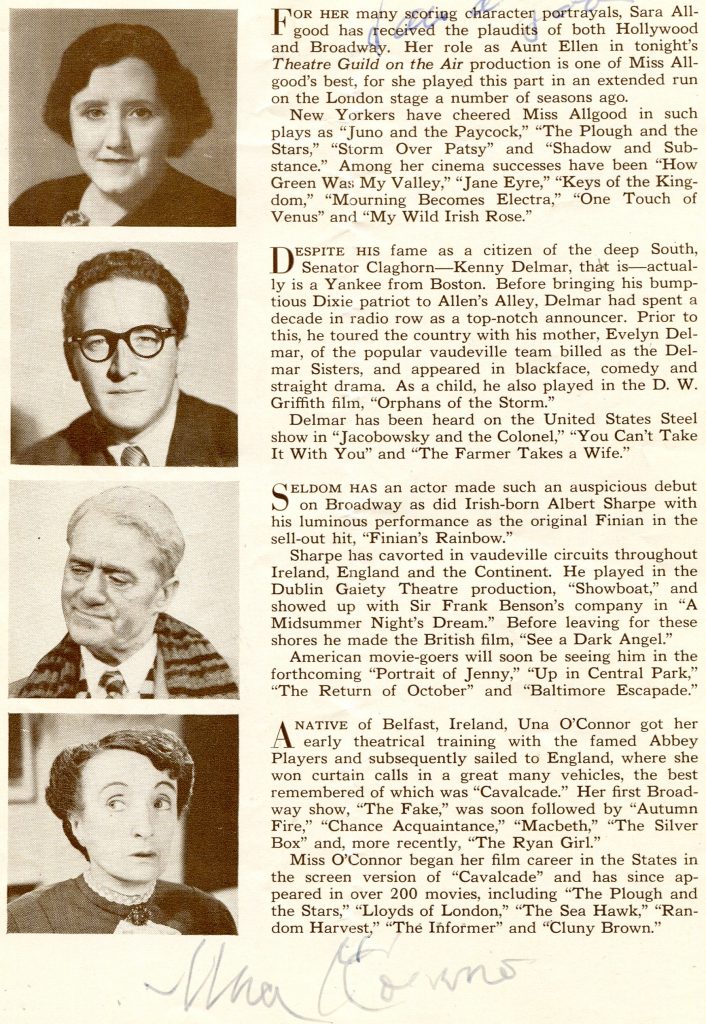

Un’s O’Connor (Wikipedia)

Born to a Catholic nationalist family in Belfast, Ireland. Although her mother died when she was two, her father was a landowner farmer, insuring that the family always had income from family land. He soon left for Australia and McGlade was brought up by an aunt, studying at St. Dominic’s School, Belfast, convent schools and inParis. Thinking she would pursue teaching, she enrolled in the South Kensington School of Art.

Before taking up teaching duties, she enrolled in the Abbey School of Acting (affiliated with Dublin‘s Abbey Theatre). She changed her name when she began her acting career with the Abbey Theatre. One her earliest appearances was in George Bernard Shaw‘s The Shewing-Up of Blanco Posnet in which she played the part of a swaggering American ranch girl. The production played in Dublin as well as in New York, opening 20 November 1911 at the Maxine Elliott Theatre, marking O’Connor’s American debut. By 1913 she was based inLondon where she appeared in The Magic Jug, Starlight Express (1915-16 at the Kingsway Theatre), and Paddy the Next Best Thing. In the early 1920s she appeared as a cockey maid in Plus Fours followed in 1924 by her portrayal of a cockney waitress in Frederick Lonsdale‘s The Fake. In a single paragraph review, an unnamed reviewer noted “Una O’Connor’s low comedy hotel maid was effectively handled.” The latter show also played in New York (with O’Connor in the cast), opening 6 October 1924 at the Hudson Theatre. A review of the New York performances of The Fake recounts details of the plot, but then mentions

…two players of more than ordinary excellence. In the third act of The Fake occurs a scene between Una O’Connor and Godfrey Tearle, with Miss O’Connor as a waitress trying a crude sort of flirtation with Mr. Tearle. He does not respond at all and the longing, the pathos of this servant girl when she has exhausted her charms and receives no encouragement, is the very epitome of what careful character portrayal should be. Miss O’Connor is on the stage for only this single act, but in that short space of time she registers an indelible impression. Rightly, she scored one of the best hits of the performance.

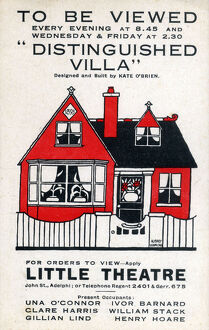

These two plays in which she portrayed servants and waitresses appear to have portended her future career. Returning to London, she played in The Ring o’ Bells (November 1925), Autumn Fire (March 1926), Distinguished Villa (May 1926), and Quicksands of Youth (July 1926). When Autumn Fire toured the U.S., opening first in Providence, Rhode Island, a critic wrote: “Una O’Connor, who plays Ellen Keegan, the poor drudge of a daughter, bitter against life and love, does fine work. Her excellence will undoubtedly win her the love of an American public.”

She made her first appearance on film in the 1929 Dark Red Roses, followed by Murder! (1930) directed by Alfred Hitchcock, and an uncredited part in To Oblige a Lady (1931).

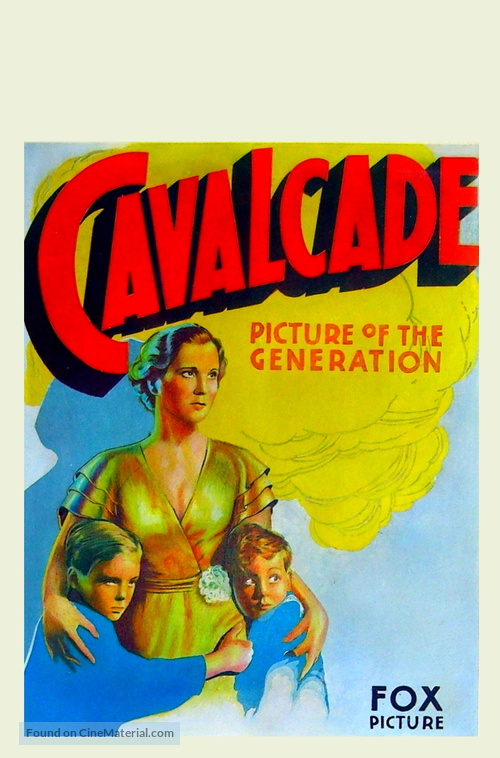

Despite her lengthy apprenticeship she had not attracted much attention. British critic Eric Johns recalled meeting her in 1931 in which she confessed “I don’t know what I’m going to do if I don’t get work…The end of my savings is in sight and unless something happens soon, I’ll not be able to pay the rent.”[ Her luck changed when she was chosen by Noël Coward to appear in Cavalcade at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1933. Expressing surprise that Coward noticed her, Coward responded that he had watched her for years and wrote the part with her in mind. She portrayed an Edwardian servant who transforms herself into a self-made woman. When the curtain came down after a performance attended by Hollywood executives, they exclaimed to each other “We must have that Irish woman. That is obvious.” Her success led her to to reprise her role in the film version of Cavalcade, and with its success, O’Connor decided to remain in the United States.

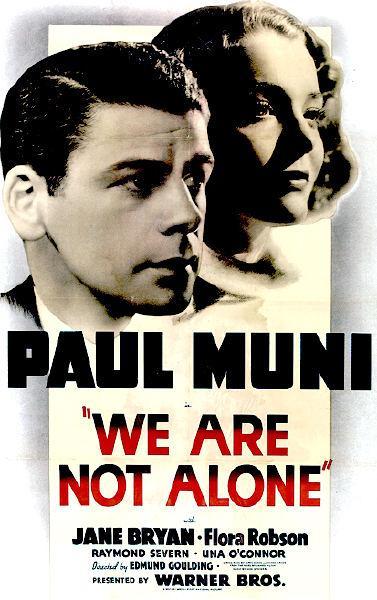

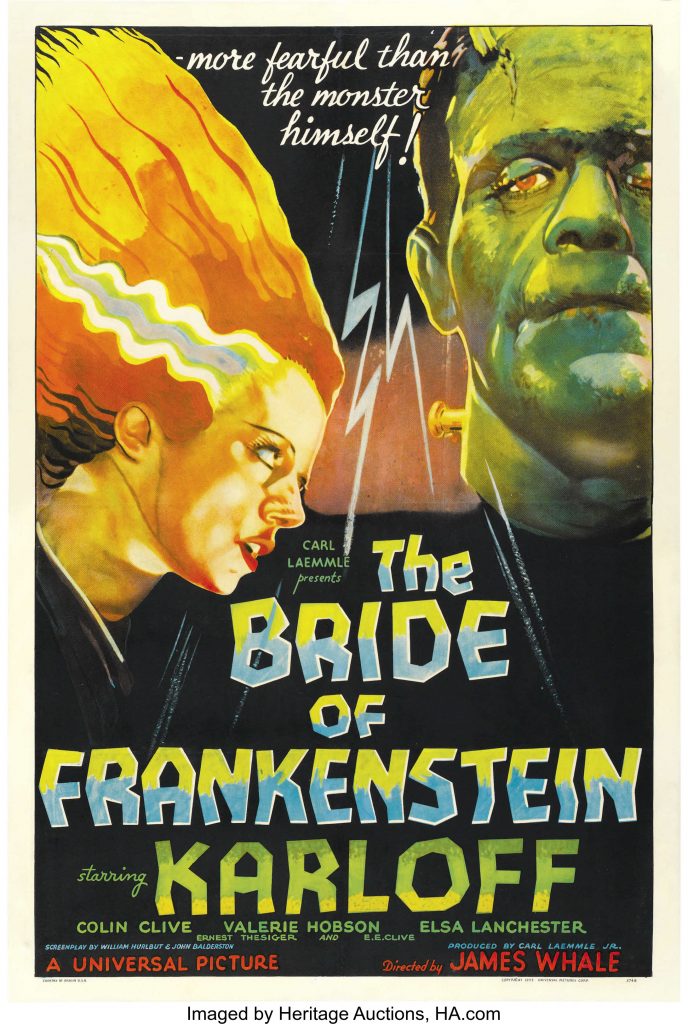

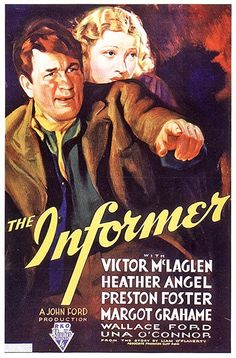

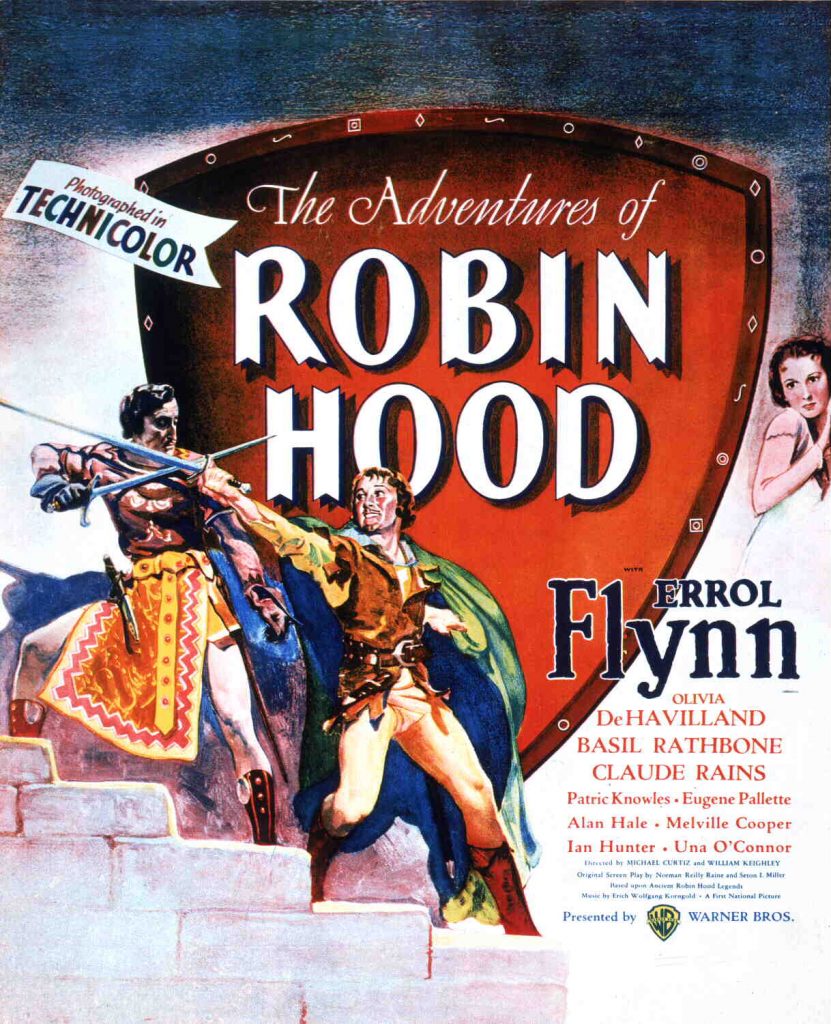

Among O’Connor’s most successful and best remembered roles are her comic performances in Whale’s The Invisible Man (1933) as the publican’s wife and in Bride of Frankenstein (1935) as the Baron’s housekeeper. She appeared in such films as The Informer (1935). Feeling homesick, in 1937 she went back to London for twelve months in the hope of finding a good part but found nothing that interested her. While in England she appeared in three television films. After her return to America, the storage facility that housed her furniture and car was destroyed in one of The Blitz strikes, which she took as a sign to remain in America.

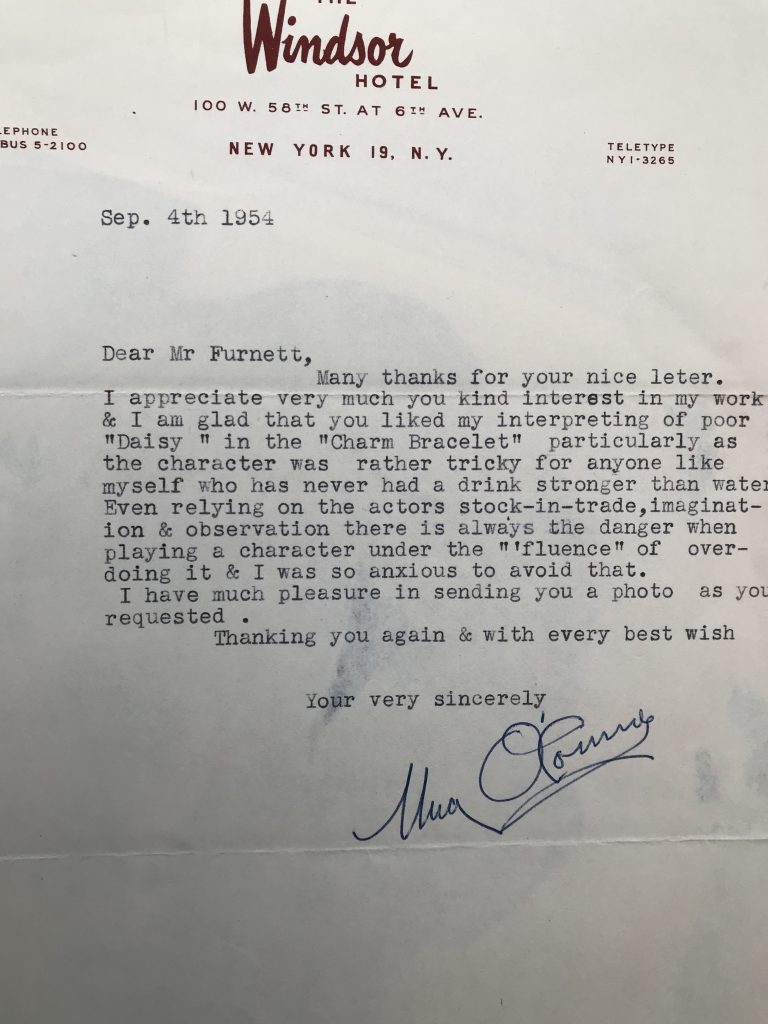

Her film career continued notably with The Bells of St. Mary’s (1944). She also appeared in supporting roles in various stage productions and achieved an outstanding success in the role of “Janet McKenzie”, the nearly deaf housemaid, in Agatha Christie‘s Witness for the Prosecution at Henry Miller’s Theatre on Broadway from 1954–56; she also appeared in the film version in 1957, directed by Billy Wilder. As one of the witnesses, in what was essentially a serious drama, O’Connor’s character was intended to provide comic relief. It was her final film performance.

After a break from her initial forays in television, she took up the medium again by 1950. In 1952 she was able to state that she had been in 38 production that year alone. In a rare article that she authored, O’Connor called working in television “the most exacting and nerve-racking experience that has ever come my way. It is an attempt to do two things at once, a combination of stage and screen techniques with the compensations of neither…” Noting that many actors dislike television work, O’Connor said that she liked it because it allowed her to play many parts. She lamented that preparation for television work was too short a period for an actor to fully realize the depths of role characterization, but that it showed an actor’s mettle by the enormous amount of work needed. “Acting talent alone is not enough for the job. It requires intense concentration, an alert-quickmindedness that can take changes in direction at the last minute…” O’Connor concluded presciently: “It sounds fantastic and that is just exactly what it is, but it also an expanding field of employment that has come to stay. As such it is more than welcome here, where the living theatre seems determinedly headed the opposite way.”

Reportedly she was “happily resigned” to being typecast as a servant. “There’s no such thing as design in an acting career. You just go along with the tide. Nine times out of ten one successful part will set you in a rut from which only a miracle can pry you.”

Her weak heart was detected as early as 1932, when her arrival in America began with detention at Ellis Island because of a “congenital heart condition.” By the time of her appearance in the stage version of Witness for the Prosecution she had to stay in bed all day, emerging only to get to the theater and then leaving curtain calls early to return to her bed. Her appearance in the film version was intended to be her last.

Eric Johns described O’Connor as

…a frail little woman, with enormous eyes that reminded one of a hunted animal. She could move one to tears with the greatest of ease, and just as easily reduce an audience to helpless laughter in comedies of situation. She was mistress of the art of making bricks without straw. She could take a very small part, but out of the paltry lines at her disposal, create a real flesh-and-blood creature, with a complete and credible life of its own.

She admired John Galsworthy and claimed to have read all his works. She once said “Acting is a gift from God. It is like a singer’s voice. I might quite easily wake up one morning to find that it has been taken from me.”

Mini biography on Wikipedia can be accessed here.