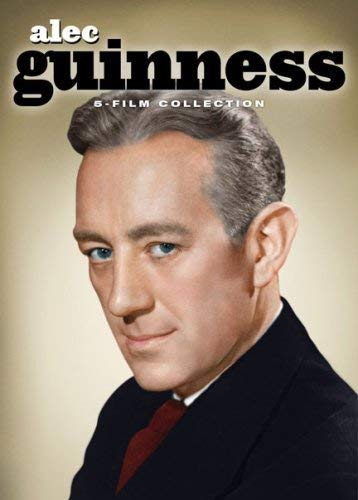

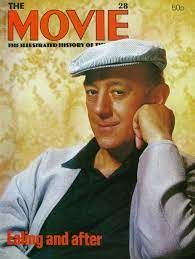

“Apart from Oliver, none of the serious highly regarded top-drawer British actors has had such a successful career in films as Alec Guinness. He has been in many very popular films,most of them enhanced by his performance. His versatility has been a byword over the past 30 years and perhaps it is the diffidence in his character which has prevented him from being a really magical actor” – David Shipman in “The Great Movie Stars – The International Years”. (1972).

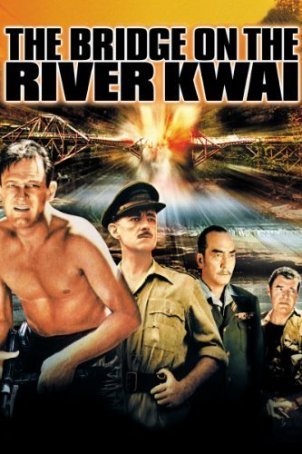

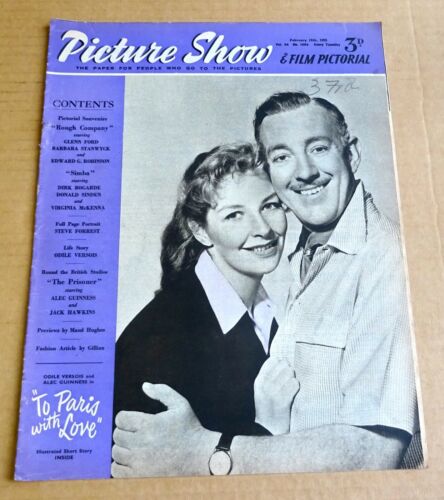

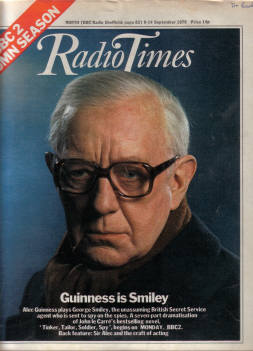

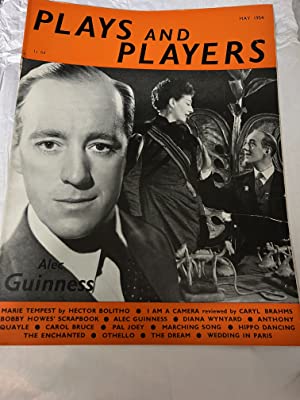

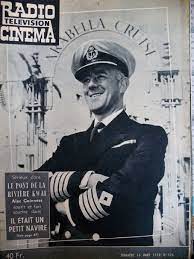

Alec Guinness was one of the most distinguished British screen actors ever. His first screen role was as Herbert Pocket in “Great Expectations” and then went on to play Fagin in “Oliver Twist”. Both of these films were directed by David Lean and Guiness made several films with Lean over the years including “The Bridge on the River Kwai”, “Laurence of Arabia”, “Dr Zhivago” and “Passage to India”. He won an Oscar for his performance in “Kwai” but he was dreadfully miscast as an Indian in “A Passage to India”. He won critical acclaim for his performance on television in the series “Tinker, Tailor, Spy” as George Smiley. Alec Guinness was also an accomplished write and had several books published. He died in 2000 at the age of 86.

Tom Sutcliffe’s”Guardian” obituary:

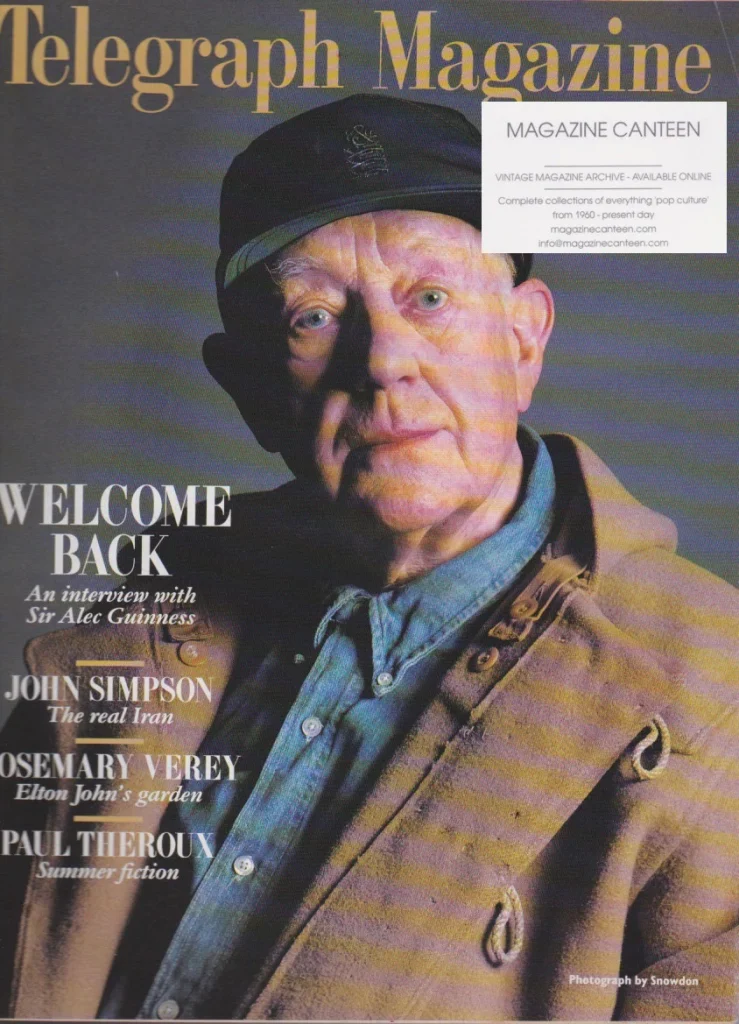

Sir Alec Guinness, who has died aged 86, was one of the best known and loved English actors of the 20th century. He was also a profoundly unostentatious and reserved man, and although he undertook a great variety of roles, all were informed at heart with the wisdom of the sad clown. It was this spiritual severity, together with those cool, clear, wide-open eyes, capable of melting on screen to the most reassuringly serene of smiles, which lent his performances force and authenticity.

In his later career, Guinness became something of an icon of spirituality and enlightened human understanding – especially after playing Obi-Wan Kenobi, in Star Wars (1977), with a notable and profound emotional charge. Subsequently, he was bemused to find himself being consulted as an agony uncle by American students, as a sort of substitute for CS Lewis. More important for him personally, his Star Wars contract guaranteed 2% of the profits, though the role had been much reduced, and he had nearly left the production.

The resulting financial security made this already fastidious actor even choosier about live stage roles. After Star Wars he was in just two West End plays, and was an unusual and sensitive Shylock at Chichester in 1984.

But Guinness was not the first great actor to find the ability, and the inclination, to learn parts after 70 much reduced. He had already avoided the theatre for six years when he came to star as TE Lawrence in Terence Rattigan’s Ross in 1960. More than any other English star of his generation, he was equally at home on stage, in film and on television – where he had an Indian summer as John Le Carré’s spymaster, Smiley, in the BBC’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1979) and Smiley’s People (1981-82) .

Guinness had an impecunious childhood, with a modest boarding-school education at Pembroke Lodge, in Southborne, and Roborough, in Eastbourne. At 18, he got a job as a junior copywriter in Arks Publicity, an advertising agency.

In his discreet autobiography, Blessings In Disguise (1985), he describes how the acting bug had bitten him. On the recommendation of John Gielgud, who assumed he was related to brewing and money, he got in touch with the formidable and eccentric Martita Hunt. She was, he noted, the first woman he had met who wore silk trousers and painted her toenails, and she coached him to audition for a Leverhulme scholarship at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. But Rada were not giving the award that year, so he enrolled at the Fay Compton studio for as long as his money lasted, and then rapidly went to work in the London theatre. He made his debut at 20, walking on in Libel! at the Playhouse.

In his unpretentious and beautifully written book, Guinness exorcised a long-suppressed anxiety about his origins. He was, he made clear, illegitimate – his name a mystery, his father probably called Geddes, the circumstances of his conception vague. His mother was Agnes Cuffe, and he was registered as Alec Guinness de Cuffe.

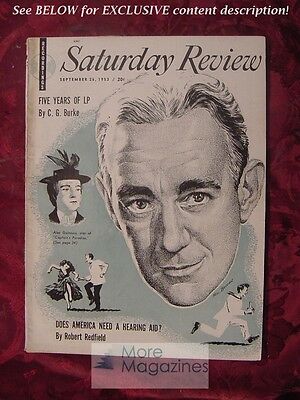

Finally, the question of his birth did not matter to him, but in the beginning it must have. A reluctance to expose himself, an almost neurotic discretion, was famously the mark of both his professional and his personal style. In a 1953 monograph about him, the critic, Kenneth Tynan, wrote: “Were he to commit a murder, I have no doubt the number of false arrests following the circulation of his description would break all records.”

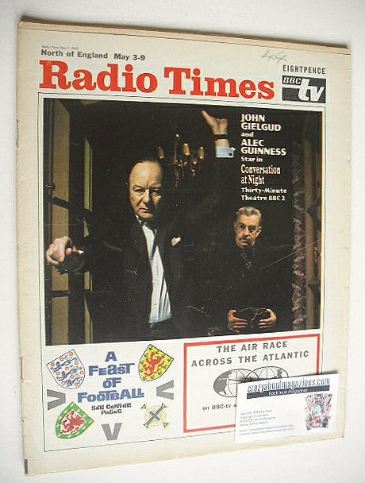

While still only 20, Guinness was a flowery Osric, in Gielgud’s Hamlet at the New Theatre. Thereafter, until the outbreak of the second world war, his career alternated between working with Gielgud, or with Tyrone Guthrie at the Old Vic, where he impressed with a modern-dress Hamlet in autumn 1938. Even the Sunday Times’s formidable critic, James Agate, conceded that Guinness’s refusal to play the role in a traditional way had “a value of its own”.

Guinness always denied having any technique as an actor – or knowing what technique might be. Yet he was proud of his gift. A favourite story, which he told quite often, concerned his time in The Seagull, in May 1936, playing the small part of Yakov. The director Komisarjevsky, a big influence, was convinced that he was pulling a rope to open the little stage curtains for the play within a play in the first act. But, as Peggy Ashcroft pointed out to Komis’s chagrin, there was, in fact, no rope.

For Guinness, the purpose of acting was to make believe. The theatre was an act of faith, whose object was to tell the inner truth about situations and feelings, not to embroider falsehood with trickery and display.

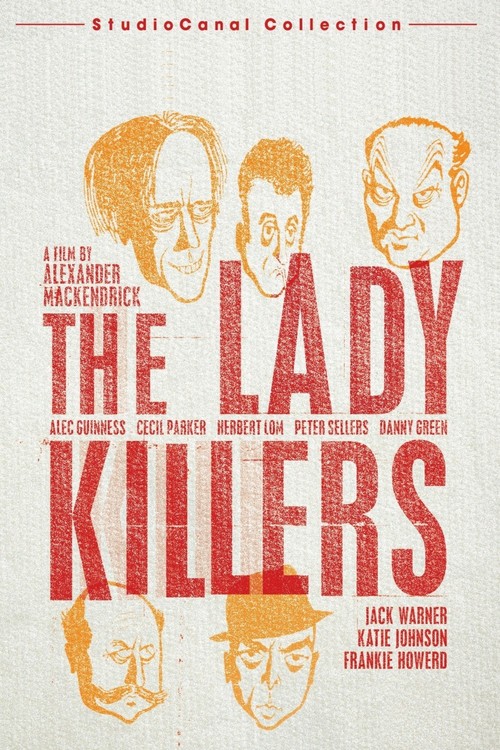

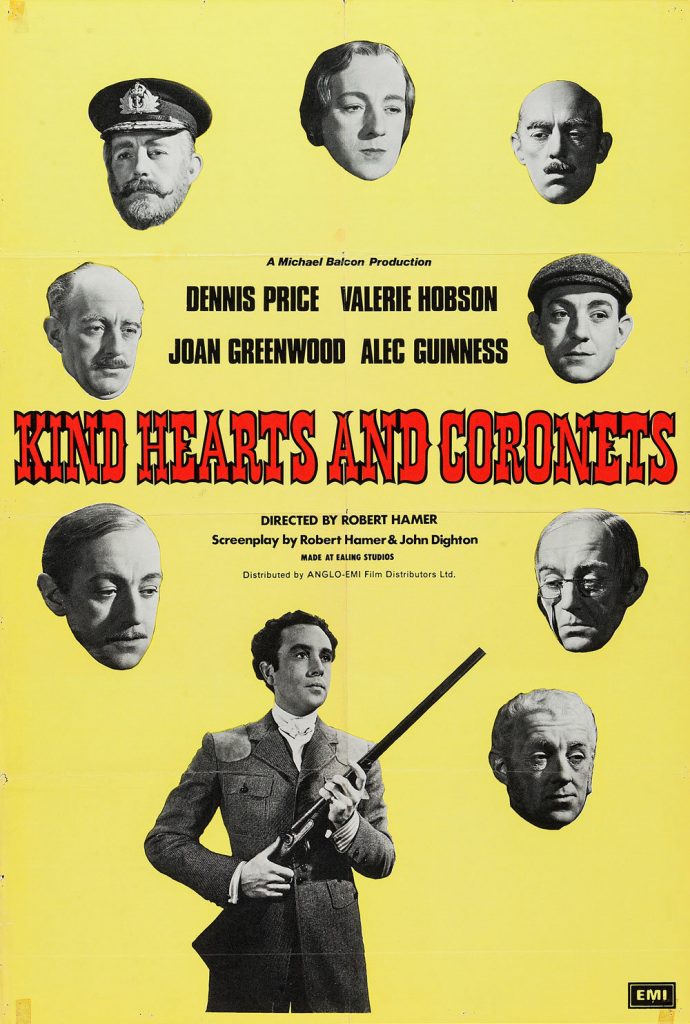

He was a master of disguise, as he demonstrated in the Ealing comedy Kind Hearts And Coronets (1949), with a multiplicity of roles. But the Kind Hearts gallery of family victims was consciously broad brush. Guinness was an actor, not an entertainer or vaudevillian like Peter Sellers, who specialised in pretence and adopting other personas. The spiritual core of his inner conviction remained the same – whatever game of actorish disguise he might play.

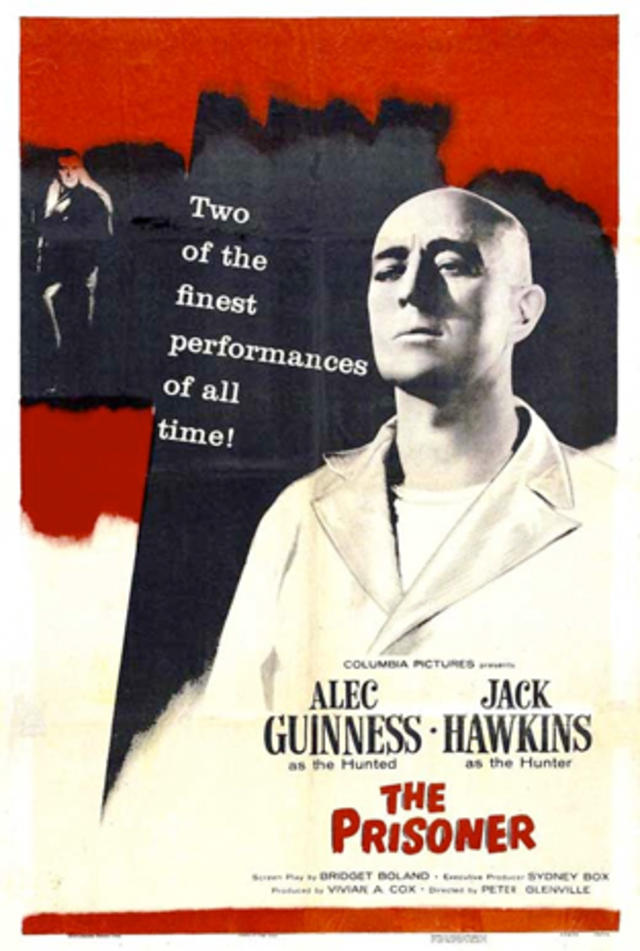

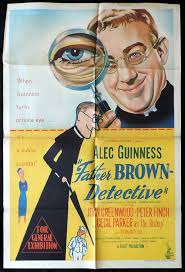

Guinness’s conversion to Roman Catholicism followed an episode in France during the 1954 filming of Father Brown, in which he was GK Chesterton’s cheery cleric-cum-detective. Walking back in the dark to the station hotel of a village near Macon, and still wearing his cassock, his hand was seized by a small boy, a complete stranger, who called him “Mon père” and trotted along beside him chatting in French. Despite his phony credentials as a cleric, Guinness felt strongly that the reality of this trust was important. When his 11-year-old son Matthew was temporarily crippled with polio, he had taken to dropping in on church and praying.

As an actor, Guinness had acute and particular tastes, an infallible instinct for the apt moment, the ideal tone, the canny strategy. When he was Fool, to Laurence Olivier’s unsuccessful King Lear (1947), he explained to me once, the irritating (to Olivier) fact that he, Alec, had the lion’s share of the reviewers’ favour was a direct consequence of Larry’s actor-managerish vanity.

“Every time Larry came on stage, the lights went up in his vicinity. All I had to do was just stay very close to him.” Guinness, of course, could not fail to be noticed – if only because he was doing so little so well.

He knew his own vulnerabilities and exploited them with courage. That lent the danger to his best performances. He had resented, for instance, the Oliviers’ assumption, in the mid-1930s, that he was Gielgud’s boyfriend. Not because he could not have been, or was ashamed or offended to be cast in that role, but because he was not, and they had no reason to assume it. In 1938, Guinness became a scrupulous husband and father – though his sexuality was complex.

Typically, he did not balk at playing the transvestite criminal Mrs Artminster in Wise Child (1967), with the then glamorous-looking Simon Ward. His Lawrence, in Ross, rang dangerously true to self. Being mixed-up, discreet, acutely intelligent and voraciously well-read fuelled the neurotic, but muffled, engine that drove him as an artist.

Being so private a personality let Guinness bring out the normally hidden interior aspects of Harcourt Reilly, in TS Eliot’s The Cocktail Party. He played this role at Chichester, Wyndham’s and the Haymarket in 1968 and 1969, as well as in Edinburgh and New York in 1950. His radio reading of Eliot’s Four Quartets were spellbinding. He was perfect material for Alan Bennett’s Old Country (1977) and Habeas Corpus (1973). In the latter, he devised – and performed alone – a typically self-revealing dance at the end.

Tynan’s fine portrait of him misinterpreted the diffidence and humility. Guinness, Tynan wrote, “never will be a star in the sense that Olivier is . . . He does everything by stealth . . . He will illumine many a blind alley of subtlety, but blaze no trails . . . His stage presence is quite without amplitude; and his face, except when, temporarily, make-up transfigures it, is a signless zero.” The suggestiveness, the wish to avoid being domineering, was a different sort of contract with the audience’s imagination. Guinness also wielded glacial fierceness and terror with unchallengeable authority.

His greatness did without Olivier’s showmanship, Ralph Richardson’s abandoned cussedness or Gielgud’s resonant lyricism. Tynan admired, but was inclined to patronise, Guinness’s poetry and versatility. At 24, in 1951, the critic was engaged by Guinness as Player King, in his second Hamlet. Guinness invested much amour propre in this production. Tynan called it “Hamlet with the pilot dropped”, and said it was cast with “exuberant oddness”.

Yet, ironically, its failure turned out to be a major factor in Guinness’s career, leading him away from the classics and Shakespeare into films, ultimately television, and new plays. Tynan found Guinness less potent in the classical arena because he expected actors to perform like concerto soloists.

I did not see Guinness’s inspirational Richard II, for Ralph Richardson’s Old Vic company, at the New Theatre (now Albery) in 1947. But his Macbeth at the Royal Court (1966) was certainly a quiet, clipped tragic victim, without the expected sexiness and physicality.

In fact, Guinness was an actor for a new theatrical style, subtle and undecorated. From the 1960s, in the West End, he mostly created roles in brand new plays, rather than challenging memories of Gielgud, Richardson or Olivier. He might have been a marvellous and unusual Lear, but, when he took the role on radio, it was underwhelming. Though his work in Alan Bennett’s plays was superb, he was far less inclined at the end of his career to accept risks as Gielgud – secure in a theatrical dynasty – famously did with Harold Pinter, David Storey and Julian Mitchell.

He was always a bit of a social upstart in an English theatre world full of great families, a self-made actor with no advantages, dependent on a very spiritual stillness and charisma. When I first met him in the mid-1970s, he had a slightly grand shyness off-stage. Yet, of all the great British stage actors, his was the busiest film career, for which his modest way of acting was flawless.

Guinness was not just an actor. He was good at drawing and did a really charming, diffident design for his own Christmas cards each year. Like Caruso, he was a natural at caricatures, especially of himself. His handwriting was beautiful. He was a very able author. Just before the war, his stage version of Great Expectations – later the basis of David Lean’s film – had been directed by George Devine.

His adaptation of The Brothers Karamazov, directed by Peter Brook in 1946, marked his return to the stage, as Mitya, after war service in the Royal Navy. He had joined as a rating in 1941, been commissioned in 1942 and commanded a landing-craft ferrying supplies to the Yugoslav partisans. He also appeared in the West End during the war, in Rattigan’s Bomber Command play, Flare Path.

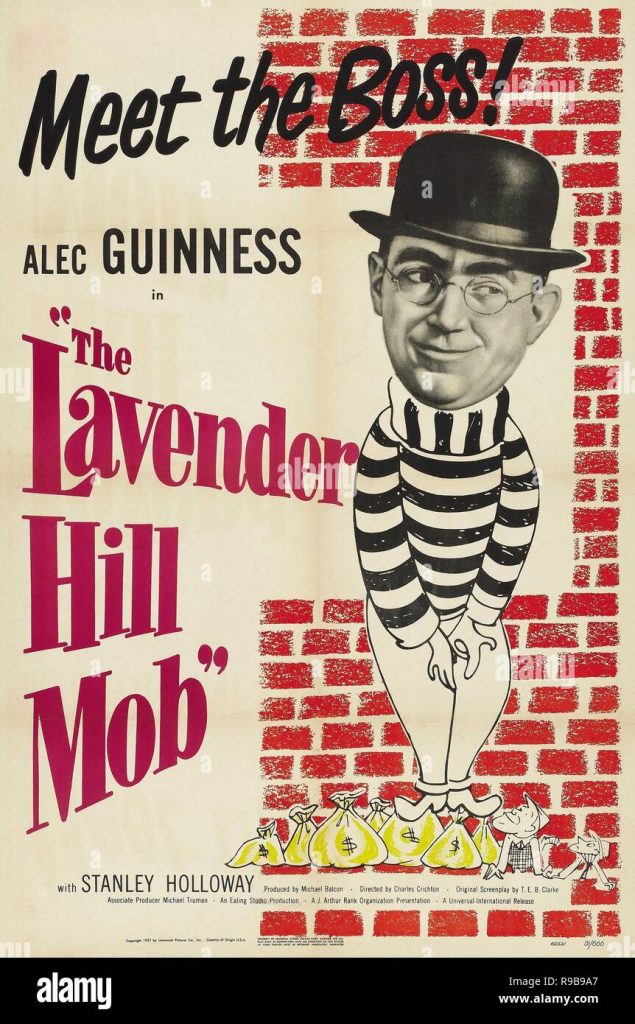

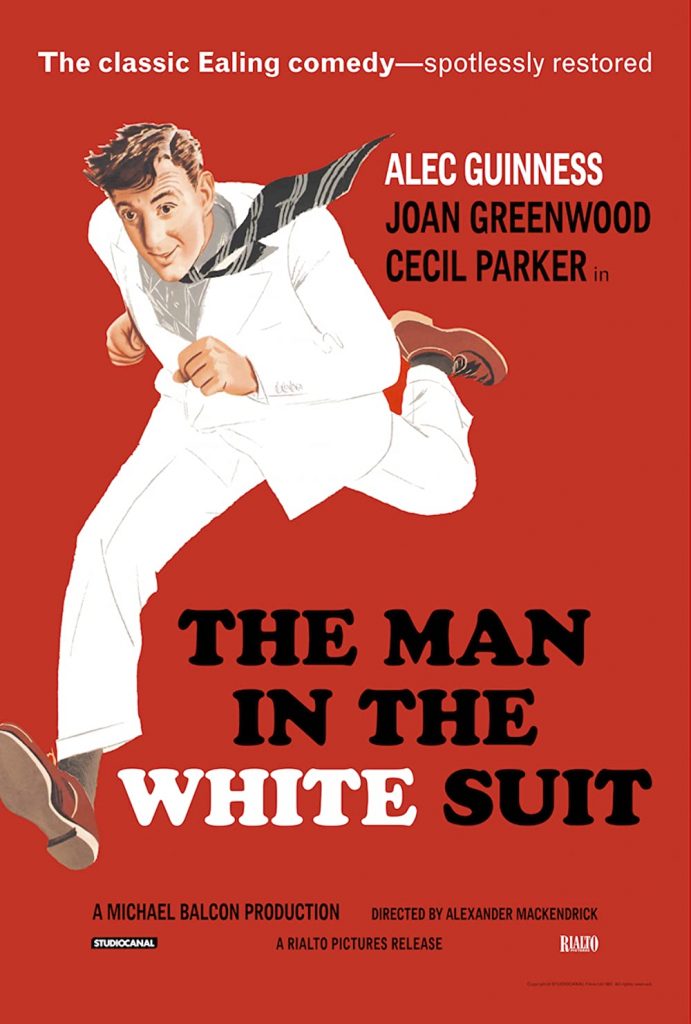

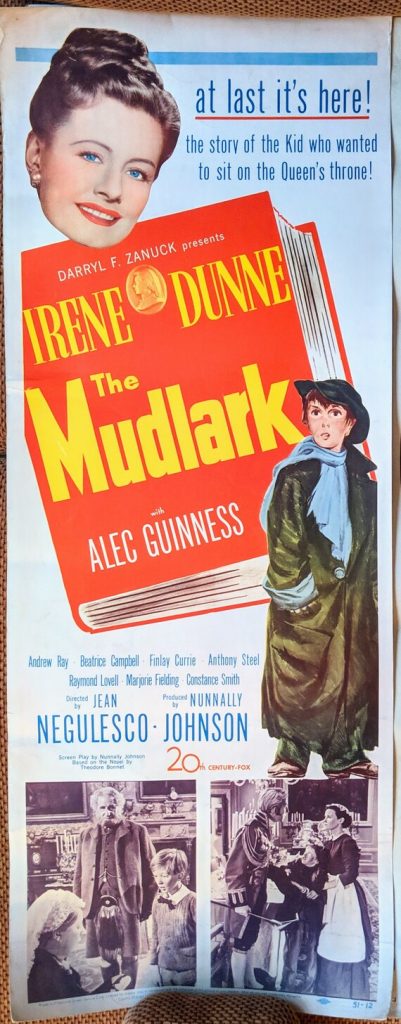

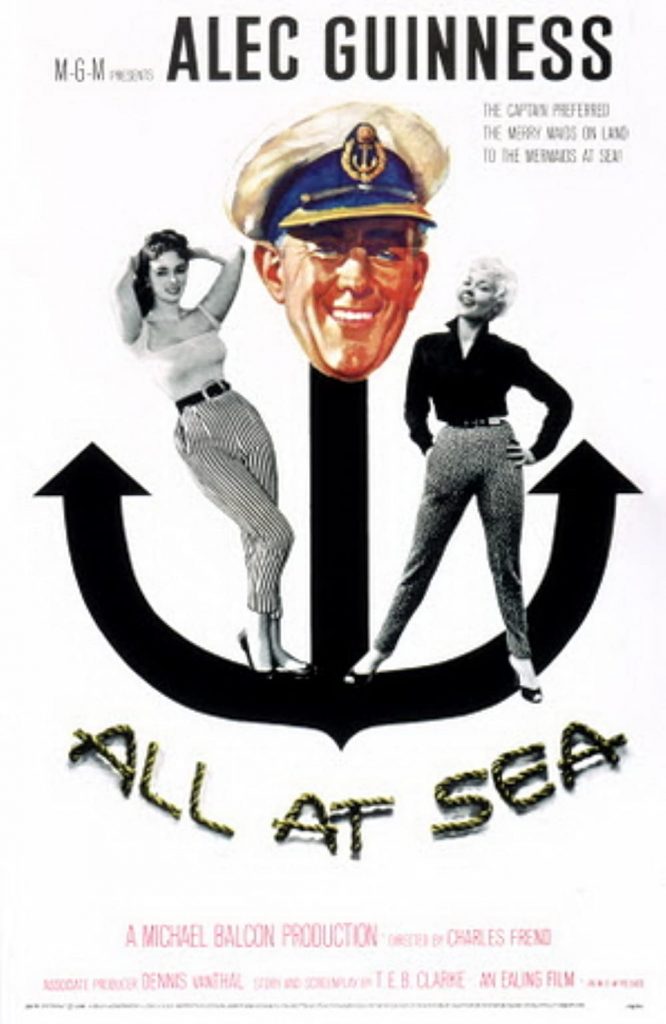

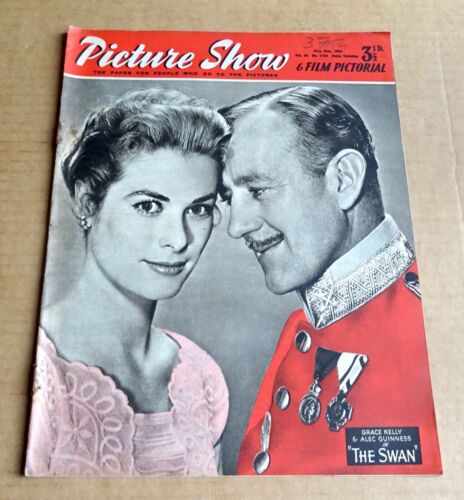

After playing Herbert Pocket, in Lean’s Great Expectations (1946), and Fagin, in Oliver Twist (1948), Guinness went on to a series of glorious Ealing comedies – perhaps most memorably as the bankteller-turned-robber Henry Holland in Charles Crichton’s The Lavender Hill Mob (1951), for which he was nominated for an Oscar, and as the criminal Professor Marcus, in Alexander Mackendrick’s The Ladykillers (1955).

His greatest film role was probably Colonel Nicholson, in Lean’s The Bridge On The River Kwai (1957), where his quintessentially English stiff upper lip under dreadful Japanese maltreatment and, eventually, obsessive unreasonableness, won him a best actor Oscar and numerous other prizes.

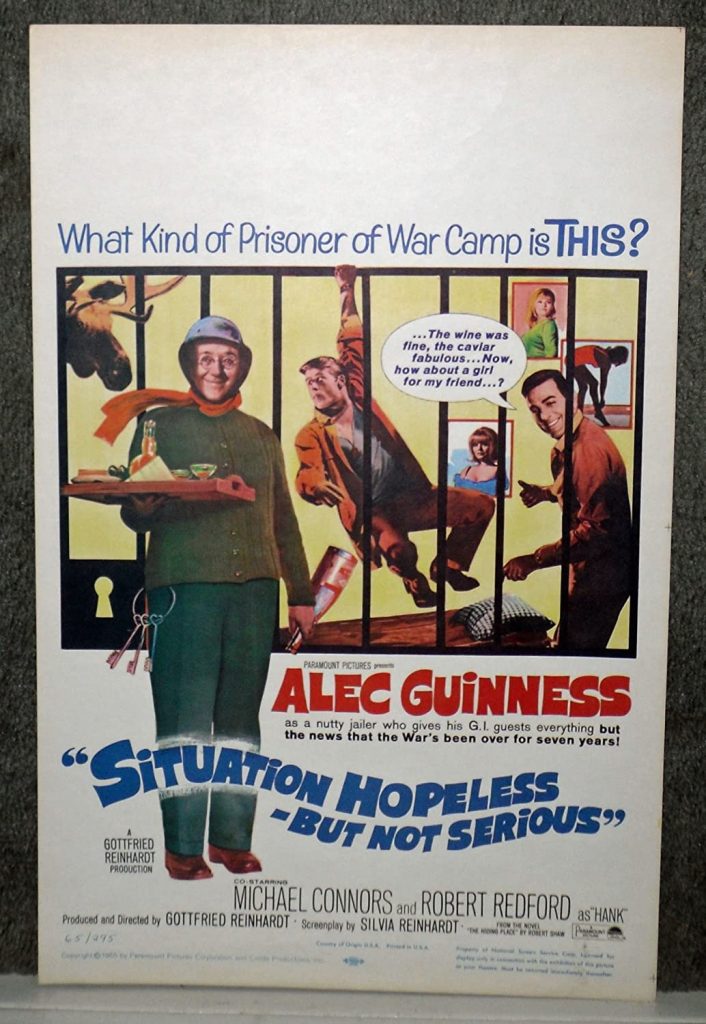

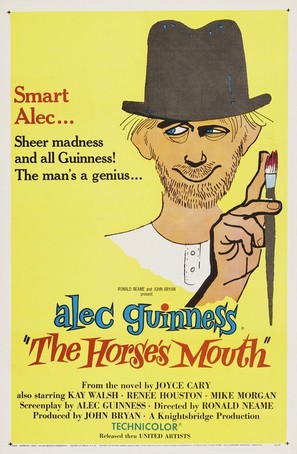

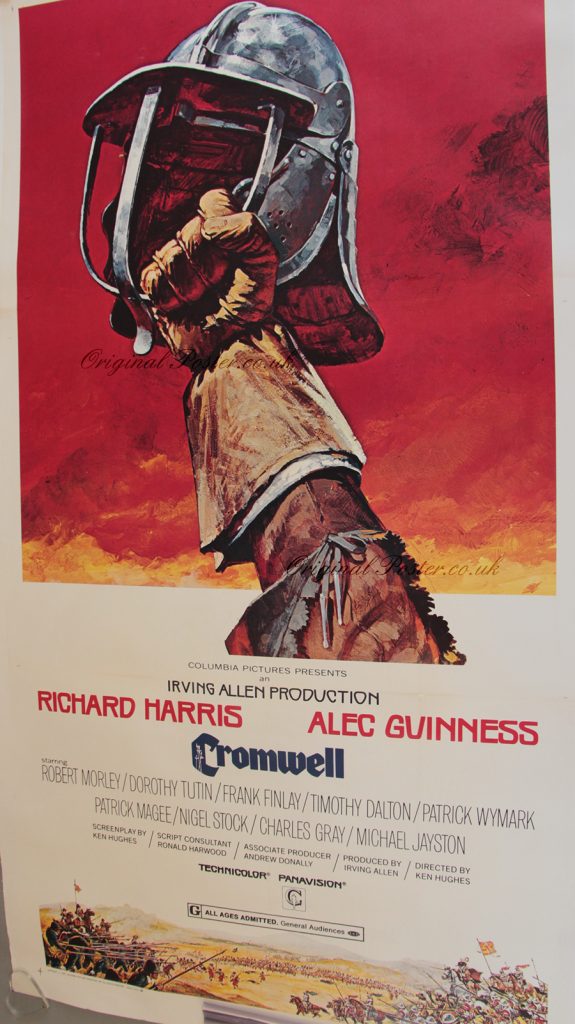

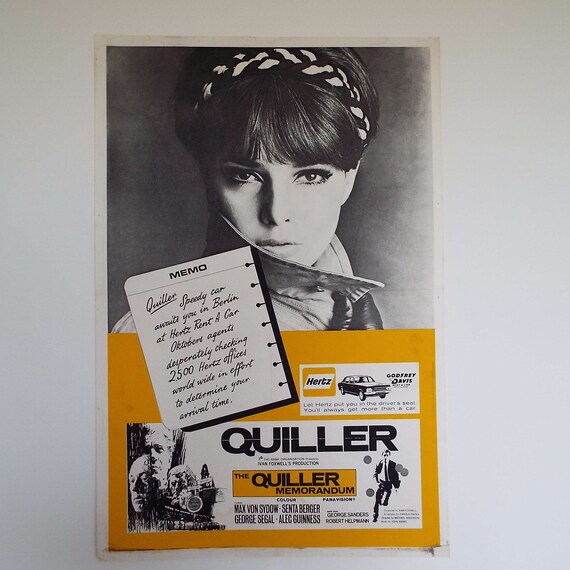

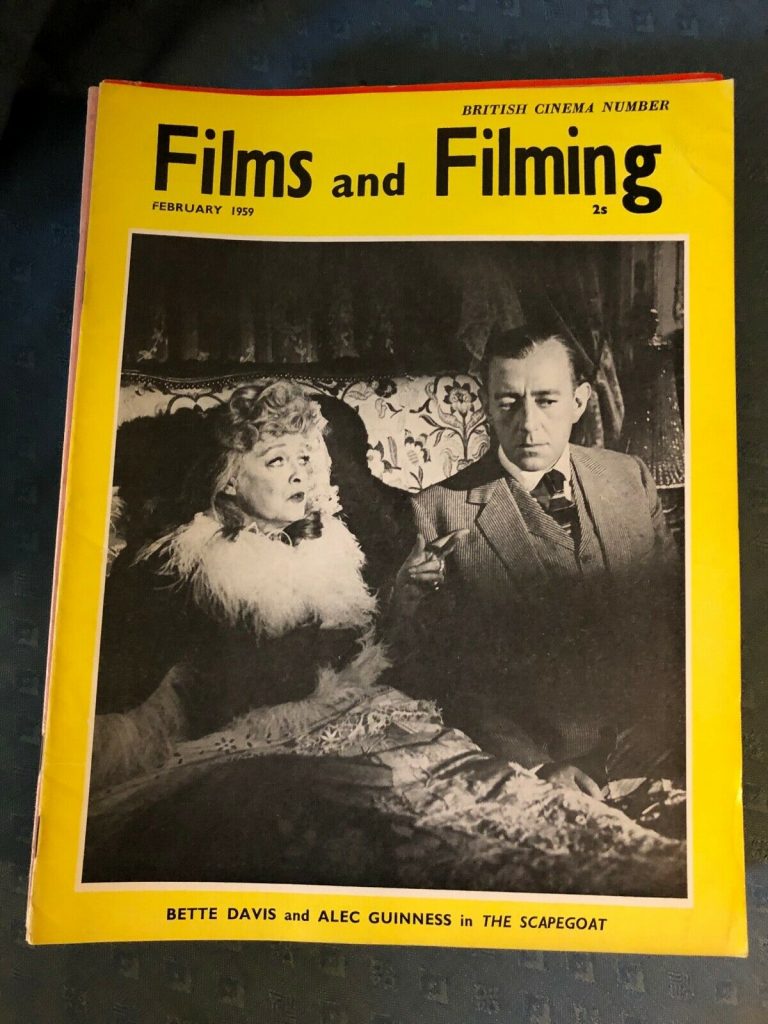

Further work included the artist Gulley Jimson, in The Horse’s Mouth (1958) – another Oscar nomination – with his own screenplay based on Joyce Carey’s novel. In 1959, he starred in Carol Reed’s Our Man In Havana, and a year later gave a brilliantly unpleasant Scottish impersonation of an irascible soldier in Tunes Of Glory. It was not followed by many more good film starring roles, and Guinness settled mostly for lucrative supporting parts in films like The Quiller Memorandum (1966), The Comedians (1967) and Cromwell (1970).

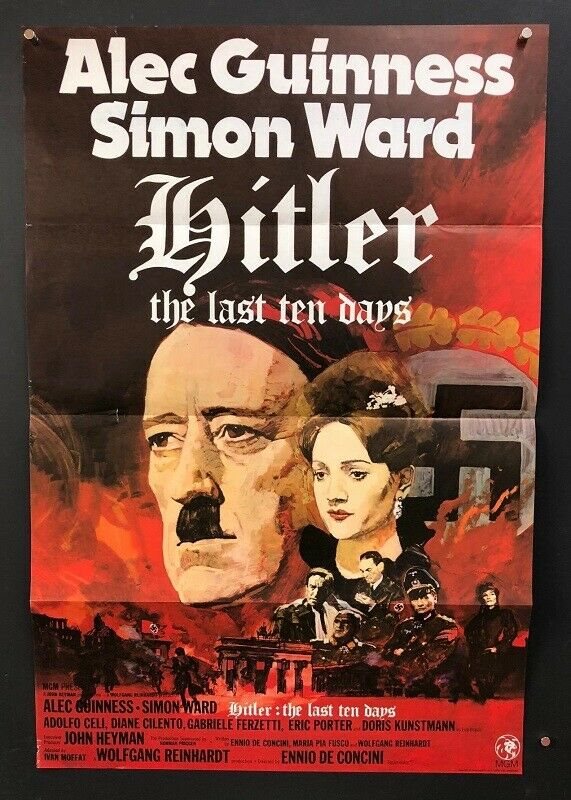

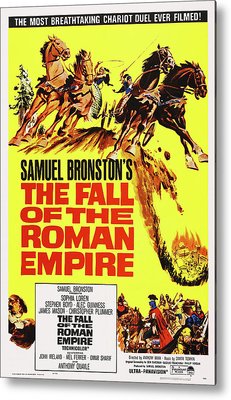

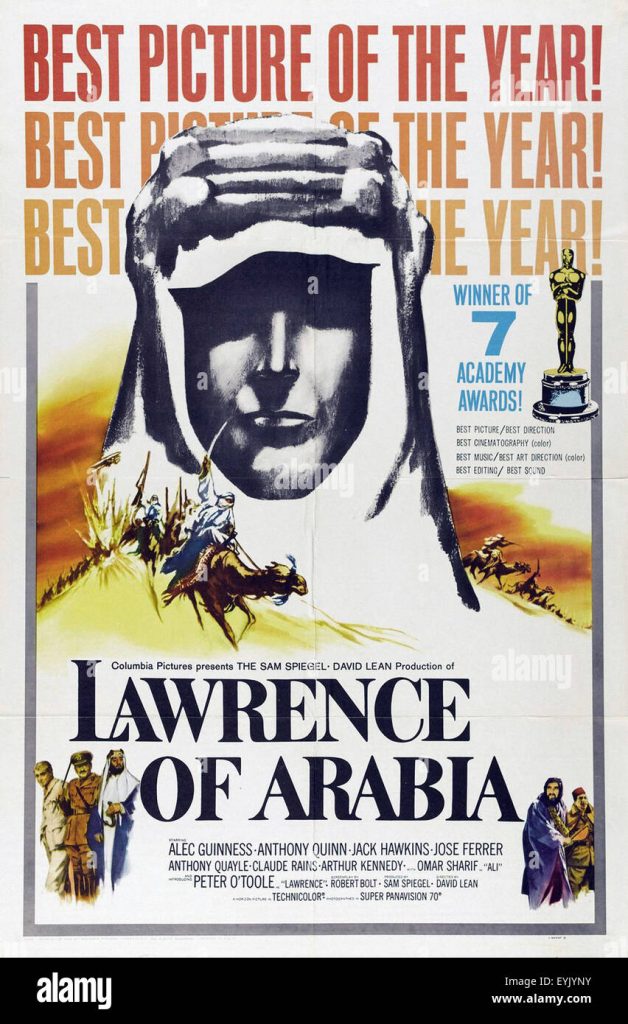

Yet some of those supporting roles were distinguished – Prince Feisal, in Lean’s Lawrence Of Arabia (1962), General Yefgrav Zhivago, in Doctor Zhivago (1965), and Professor Godbole, in A Passage to India (1984). In Anthony Mann’s The Fall Of The Roman Empire (1964), Guinness’s Marcus Aurelius was one of the film’s few redeeming features.

He was again nominated for an Oscar with Star Wars (1977), and six years later appeared in its sequel, Return Of The Jedi. Yet another Oscar nomination followed his appearance as Dorrit, in Christine Edzard’s epic adaptation of Dickens’s Little Dorrit (1988).

At the end of the 1970s, he achieved a new fame with his television appearances in the BBC2 adaptations of Le Carré’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and Smiley’s People. These works were effectively his screen monument, and for which he achieved Bafta awards.

Guinness was a charming, fascinating and elusive companion. He did not enjoy playing the star, though he liked the respect he got when visiting famous restaurants. From the mid-1950s, he lived in a modest way outside Petersfield, in Hampshire, with a large garden that much occupied his wife, Merula, whom he had married in 1938.

He had a small circle of particular friends, many outside the theatre. For years, he and Merula were close to Rachel Kempson and Michael Redgrave. If one visited him in his dressing room in the West End in the 1970s, one might find a surprisingly broad collection of people there, many of whom were never destined to discover what the others’ link with the great actor might be. He preferred to keep his friends separate; he was a one-to-one person.

He liked good food and drink. His favourite London hotel was the Connaught, with its superb cuisine. He was not a club man. He was knighted in 1959 and made a Companion of Honour in 1994.

Anybody outside his immediate circle was intrigued by the Guinness enigma. But the reserve through which that attractive generosity and warmth powerfully shone was, for him, an impenetrable and necessary protection.

He is survived by Merula and his son, Matthew.

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

A “Guardian” article by Xan Brooks on Alec Guiness’sbest movies can be found here.