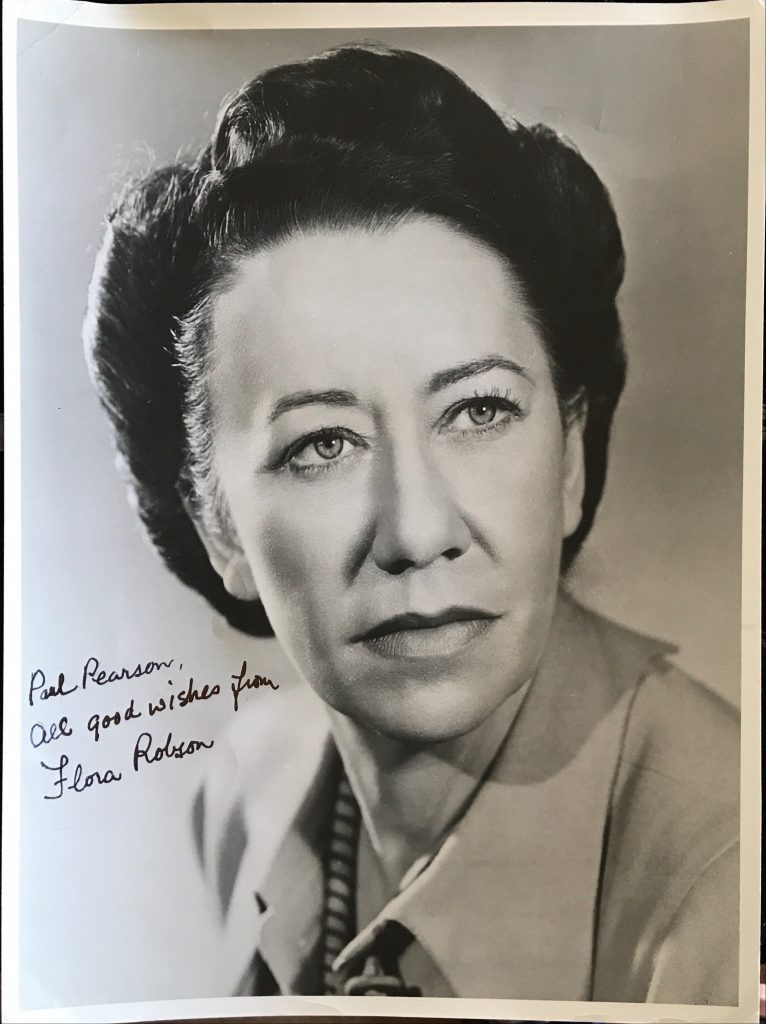

“All the great stars have a quality which cannot be exactly pinned down. You can say that Flora Robson has a beautiful speaking voice, but how do you define that stillness, that urgent inner momentum, the flick of humour, the smile that can light up a room – the combination of all four? Perhaps the clue to her art is in the stillness, always an indication of confidence, of an artist having mastered his art. It would have been her wish, it is known, to have been beautiful but she is much more interesting than most of her contemporaries. She has played a wider spectrum than most actresses but is in the end better in sympathetic parts. – David Shipman – “The Great Movie Stars – The Golden Years”. (1970)

Flora Robson was a magnificent character actress who made many films in Britain and in Hollywood from the 1930’s to the 1970’s. Although she played wifes and mothers, she seemed especially effective as single women e.g. her housekeeper Ellen Dean in the 1939 version of “Wuthering Heights” and Muriel Manningford in “2,000 Women”. She was created a Dame of the British Empire in 1960. Flora Robson died in 1984. Her obituary in “The New York Times” can be accessed here.

TCM Article:

In the 1930s, a British film fan magazine wrote, “Although she has a strong personality of her own, she has always kept the faculty, comparatively rare in film stars, of losing her own identity in the role she is playing. For this reason, she may never be a great star, in the ordinary sense. But her characterizations will live in your memory long after those of the more conventional type of screen star have been forgotten.” Had Flora Robson been beautiful, she would have been a major star; but while her talent made her worthy of stardom, her 5’10″stature and plain features forever relegated her to the ranks of the truly great supporting actresses. Her true vocation was the stage.

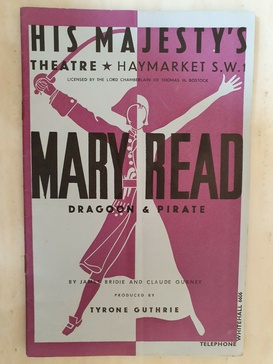

Born Flora McKenzie Robson in South Shields, Durham, England on March 28, 1902, she was one of eight children born to a former ship’s engineer and his wife. Her talent for recitation became apparent at the age of six and after attending Palmers Green High School, her father paid for Robson to study at the famed Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, where she won a Bronze Medal in 1921. Following graduation, she performed in the West End, making her debut in Clemence Dane’s Will Shakespeare, but after two years of regional theater, the financial instability of acting led her to take a job as a welfare officer in a Shredded Wheat factory for several years. While there, she organized theater productions for the workers.

She returned to acting in 1929 (ironically at the start of the Great Depression) by joining the Cambridge Festival Theatre and in 1931 had secured a position at the Old Vic in London, where her career took off. Now one of England’s top stage actresses, she moved to an apartment at 19 Buckingham Street, across the hall from the great American singer/actor Paul Robeson and his wife. In January 1933, Robeson approached Robson about co-starring with him in Eugene O’Neill’s play about an interracial marriage, All God’s Chillun’. Director Andre Van Gyseghem wrote, “Robeson was Jim and the result was terrifying in its intensity. Time and time again directing Flora and Paul I had the feeling of being on the edge of a violent explosion. I had touched it off, but the resulting conflagration was breathtaking. They literally shot sparks off each other. Seldom have I seen two performers fuse so perfectly. It was so intimate and intense that I felt, at times, I should apologize for being there. Watching it was sometimes more than one could bear at such close range. Robeson’s technique was not Flora’s. She was an expert actress with tremendous emotional power. She absolutely hushed audiences as she stripped the meager soul of Ella. But her technically superb performance found a perfect foil in Robeson’s utter sincerity.” Dame Sybil Thorndike, who attended the play, later wrote “When I saw Flora, I thought to myself, here we have the making of one of England’s greatest tragic actresses. Flora was not beautiful in the conventional sense; in fact she was rather plain. But she took the role of Ella beyond racial themes and portrayed the devastating love/hate relationship between the couple to the point that it was almost too painful to watch.”

Robson’s fame as a theater actress brought her to the attention of British filmmakers. Her first film, A Gentleman of Paris (1931) did not make a big splash, nor did the other three films she made in 1932. It was in 1934, when she was a bona fide theatrical star, that Robson began her real film career by playing a queen. It would almost become typecasting for her. In The Rise of Catherine the Great (1934), she played the Russian Empress Elisabeth, which led to her being chosen to play Queen Elizabeth I in Alexander Korda’s Fire Over England (1937), co-starring Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. Of the role Robson wrote, “Provocative, aggressive, possessive and perhaps a bit temperamental, Elizabeth was every inch a queen. She was essentially a woman of action, and that is just the kind of women I like best to portray. Whether they are characters of actual history, or folk-lore or of pure fiction, such women whose lives and work were more important than their loves aremuch more in tune with our modern ideals and tempo of life than many of the silken sirens who have figured as the heroines of sexy and sentimental film in the past.”

Hollywood came calling after Robson’s fiery portrayal of Elizabeth. Among them, Samuel Goldwyn, who wanted Robson for his Wuthering Heights (1939) once more co-starring her with Laurence Olivier. 1939 saw Robson in no less than five films, both in the United States (We Are Not Alone as Paul Muni’s wife) and England (Poison Pen). The latter was Robson’s only starring role, as the writer of poison pen letters who might be a murderer, and it was promoted with the following advertising copy, “The name of Flora Robson at the head of the cast is a sure sign that this is something very much more than a mere recital of horror and tragedy. This is one of the few opportunities the screen gives of seeing England’s finest emotional actress.”

Robson found acting for the screen to be vastly different than the stage: “The slightest touch of self-consciousness on the screen shows. I’ve learnt from bitter experience. In the theatre one feels the audience. One overacts. But the camera, like a huge eye a yard away, snaps up everything. [Famed Hollywood cameraman Hal Rosson helped me to overcome the inevitable theatrical exaggeration and to eliminate certain small mannerisms of expression which, while perfectly natural on the stage, were little short of grotesque when translated to the screen. I knew of course that the camera demanded much less emphasis of facial expression than the stage, but I had not realized that it required under-emphasis, that is, less than would be natural. Everything like this has to be entirely eliminated for the camera, and you must even speak with as little lip movement as possible.”

Although war had broken out in Europe, Robson remained in the United States, where she accepted a role on Broadway in Ladies in Retirement (1940), with rehearsals to begin after once more portraying Queen Elizabeth on the screen. This time, she was cast opposite Errol Flynn in Michael Curtiz’s The Sea Hawk (1940), beating out such competition as Gale Sondergaard, Geraldine Fitzgerald and Judith Anderson. It was to be the second of a two-picture deal with Warner Bros., but the film ran into delays and she accepted a role in the George Raft film Invisible Stripes (1939). The Sea Hawk finally went into production and despite the many stories of Flynn’s bad behavior on the sets of his films, Robson remembered him fondly. “We hit if off from the beginning. He was naughty about his homework. I told him that because he couldn’t remember his lines it would hold up the picture and I would be delayed going to New York to do a play. When I told him this, he was very kind and learned his lines to help me: the work went so fast we were finished by four in the afternoon on some days. I remember Mike Curtiz saying to him, ‘What’s the matter with you? You know all your words.'”

Robson’s lifelong preference for the stage over film work puzzled movie executives. “The people [in Hollywood] find it very difficult to understand the English actor’s off-hand attitude towards the film industry.” That attitude led her to turn down the role of Mrs. Danvers in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940) because she wanted to return to the stage. Once the run of Ladies was over, she returned to London in 1941 and remained there until the end of the war, doing theater. She returned to Hollywood in 1945 to play the role which gave her the only Academy Award nomination of her career, Saratoga Trunk (1945) opposite Ingrid Bergman. It was an odd role for Robson, that of a scheming mulatto slave and it required her to act in makeup that was close to blackface. Other films in the 1940s included Caesar and Cleopatra (1945), once more with Vivien Leigh and Michael Powell’s Black Narcissus (1947). However, it was her stage work that was the most important, especially her legendary performance as Lady Macbeth in 1949 and as Paulina in John Gielgud’s 1951 production of The Winter’s Tale. As a Shakespearian actress, it was said she “took Shakespeare’s utterances on her lips with a natural dignity and beauty.”

Robson’s career continued throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s with her accepting the occasional film, as in 55 Days at Peking (1963) playing the Dowager Empress Tzu-Hsi ; and Murder at the Gallop (1963), one of the very popular Miss Marple films starring Margaret Rutherford. There was also television work, both in the United States and Britain. By 1969, Robson, now in her late 60s had retired from the theater, but not before being honored with a CBE (Commander of the British Empire) from Queen Elizabeth II, which was elevated to a DBE in 1960, making her “Dame Flora Robson”. This last was in recognition of her many unpublicized charitable works. She also had the distinction of having a theater named after her: The Flora Robson Theatre in Newcastle, England. Her homes in Brighton were designated with plaques after her death as well as the doorway of the Church of St. Nicholas in Brighton, where she attended.

Flora Robson ended her career with television movies and mini-series including Gauguin the Savage and A Tale of Two Cities (both in 1980), with her last appearance as one of the Stygian Witches in Clash of the Titans(1981), also co-starring Laurence Olivier. She died in Brighton, England on July 7, 1984.

by Lorraine LoBianco

The above article can be also accessed here.