Vera Lynn

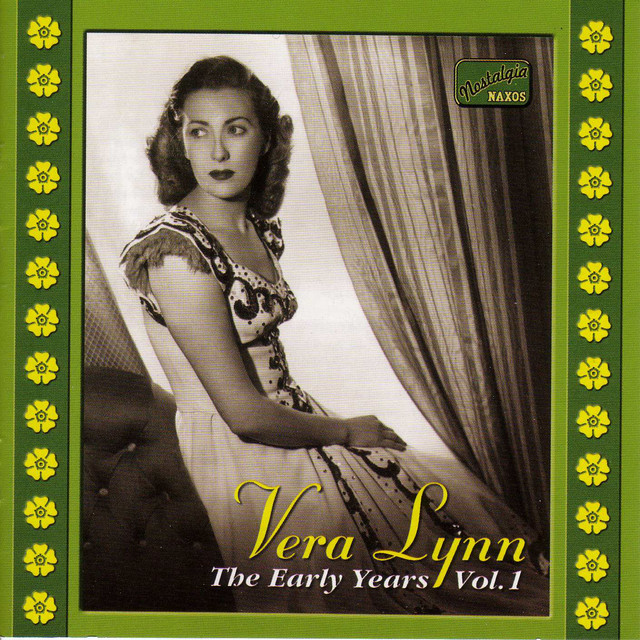

The magnificent Dame Vera Lynn became in 2009 the oldest living artist to have a Number 1 album chart at the age of 92.

The Forces Sweetheart of World War Two published her autobiogaphy in 2010 and has given several television performances which show her genuineness and gentleness.

She made three films in the 1940’s, the most popular been “We’ll Meet Again” in 1942 with the beautiful Patricia Roc.

A boxed set of these three movies has just been rele

ased on DVD in 2010

Interview with Dame Vera Lynn in “Saga” magazine can be accessed here.

Dame Vera Lynn obituary

Singer known as the ‘Forces Sweetheart’ whose recordings of We’ll Meet Again and The White Cliffs of Dover shaped the national mood in wartime Britain

Dave LaingThu 18 Jun 2020

At the start of the second world war, Vera Lynn, who has died aged 103, was an up-and-coming dance band singer. By 1945, this working-class young woman had become a symbol of the British wartime spirit, with a status comparable to that of the patrician prime minister, Winston Churchill. After the war, her friend Harry Secombe liked to joke that “Churchill didn’t beat the Nazis. Vera sang them to death.”

Lynn’s iconic status as the “Forces’ Sweetheart” was due to the success of her radio series, Sincerely Yours, which linked the soldiers at the front with their loved ones at home. In 1944, she visited the troops in Europe, the Middle East and Asia, which kindled her lifelong commitment to the welfare of veterans, especially those of the Burma campaign. Above all, her celebrity was due to her hit songs. Such numbers as We’ll Meet Again and The White Cliffs of Dover caught and moulded a national mood, despite the harsh criticism her crooning style provoked from some politicians and BBC managers.

After VE Day, Lynn resumed her career as a variety artist and recording star, but her association with wartime Britain remained central to her identity and reputation throughout her long life. Until very recently, Lynn was a prominent presence at commemorations of the war. Her place at the heart of national life was officially recognised when she was made OBE in 1969, a dame in 1975 and a Companion of Honour in 2016; her 100th birthday, in March 2017, was marked by the release of a new album and a concert in her honour at the London Palladium. Equally, she became part of popular culture as cockney rhyming slang made her synonymous with gin, chin and skin (as in cigarette papers), she was hymned by pop singers of later generations including Pink Floyd and Ian Dury, and she was the subject of numerous comic impersonations, something she tried unsuccessfully to control through court action in the 1950s.

She was an unlikely candidate for the role of national heroine. Born in the penultimate year of the first world war, she was the second child of a working-class family who lived in a small apartment in East Ham, east London. Her father, Bertram Welch, had various jobs, including working as a plumber and docker. Her mother, Annie, was a dressmaker.

Vera’s vocal talent was evident from a very early age. After singing at family parties, she made her public debut at a local working men’s club aged seven, billed as a “descriptive child vocalist”. Adopting her grandmother’s maiden name, Vera Lynn soon joined a juvenile concert party, the Kracker Kabaret Kids.

In 1932, still only 15, she was signed up by Howard Baker, a bandleader and agent, who supplied dance bands for functions throughout the East End of London. A brief period with Billy Cotton’s band followed, culminating in a week’s engagement in Manchester, from which Cotton sent Vera home. He later described this as “the worst day’s work I ever did”. Cotton’s loss was the pianist Charlie Kunz’s gain. Vera sang with his band on BBC broadcasts.

Unusually for the time, Kunz gave Lynn free rein to choose the songs. She visited music publishers in Denmark Street, London’s Tin Pan Alley. There Vera met Walter Ridley, of the Peter Maurice company, who not only found songs for her but undertook to transpose them to a suitable key for Lynn’s unusually deep voice, which was variously described in the press as a “rich contralto” and “a freak mezzo-soprano with an irresistible sob”.

From 1937 to 1940, Lynn worked with another top bandleader, Bert Ambrose, who was impressed by her enunciation of lyrics. She toured variety theatres with the Ambrose Octet and took part in broadcasts for the BBC and for Radio Luxembourg, in a show sponsored by Lifebuoy soap. There was also a debut television broadcast from Alexandra Palace in 1938. The following year, she recorded We’ll Meet Again for the first time, shortly before a newspaper columnist claimed she was selling more records than either Bing Crosby or the Mills Brothers.

Advertisement

Her growing success was reflected in the growth of her fan mail and in her increasing salary. In 1938, she was able to move her family to a new house in Barking and to buy a fur coat and her first car, an Austin 10.

In 1939, a new saxophonist joined the Ambrose orchestra. Harry Lewis soon showed his admiration for Vera and in 1941 they were married. Very soon afterwards, the band felt the full impact of the war as Lewis and others volunteered for military service. As members of the RAF they set up the Squadronaires, a dance and jazz group that continued after the cessation of hostilities. Lewis was to give up his career in the late 1940s to become Lynn’s personal manager. He became well known for answering the phone with “What do you want her for?”

By 1941 Lynn was a star in her own right and she left Ambrose to begin a solo career. She soon found work on the variety theatre circuit, beginning at Coventry Hippodrome, often topping the bill working with only a piano accompanist.

At this time, BBC producers were seeking new ideas for the Forces Programme, which had been established to broadcast to the British expeditionary force. Howard Thomas, later a pioneer of commercial television, proposed a format that would be “a letter to the men of the forces in words and music”. Lynn had previously been voted “No 1 forces sweetheart” by Forces Programme listeners and was an ideal choice to read and sing such a letter. To quote the music historian Paul du Noyer, “she was not a glamorous sex-bomb pandering to the lonesome soldiers’ lower instincts. Instead she aroused a wistful yearning for the idealised fiancee.”

It was an immediate success. Up to 2,000 messages were received each week from domestic listeners from which Lynn read out a small sample. She also sent out signed photographs and brief letters to servicemen at the front. This occasionally led to misunderstandings, as when she was accosted by a wife who had found a letter to her absent husband and accused Lynn of stealing him.

Above all, Sincerely Yours was about Lynn’s voice and her songs. Three songs came to embody the wartime spirit and became indelibly associated with her. Yours (recorded in 1941) was a straightforward song of love and fidelity; We’ll Meet Again (1939) expressed a mood of fervent optimism and was described by Lynn as a “greetings card song: a very basic human message of the sort people want to say to each other but find embarrassing actually to put into words”; and The White Cliffs of Dover (1942) was intensely patriotic – despite having been composed by Americans.

While Sincerely Yours had exceptional audience numbers, behind the scenes at the BBC controversy raged. A committee minute noted that the assembled members deplored Sincerely Yours but “noted its popularity”. The opposition to the show was part of a wider dislike of crooners, whose vocal style was held to be over-sentimental and tinged with Americanisms. Male crooners were especially denigrated but Lynn was in the eye of the storm because her show attracted such a large listenership. It was attacked in parliament as liable to undermine the morale of British fighting men. One MP went further in criticising Lynn’s speaking voice as “refaned cockney”. She was stung into responding that “millions of cockneys are fighting in this war”.

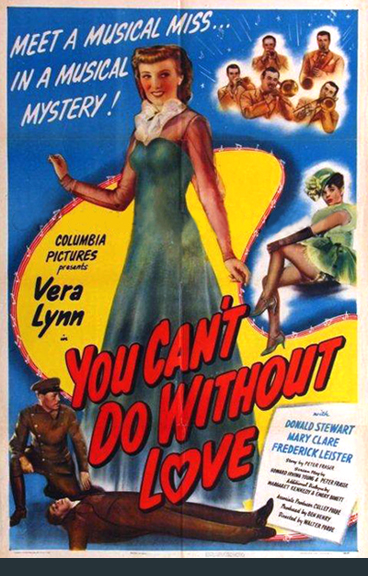

So great was her public profile that she starred in three films between 1942 and 1944. They traded on Lynn’s persona, to the extent that We’ll Meet Again and Rhythm Serenade borrowed titles of her songs. All had wartime themes as a backdrop to lightweight romantic stories, which did not fulfil the promise of the title of the third, One Exciting Night. While they served their morale-boosting purpose, Lynn did not pursue a career in cinema after the war.

The most affecting phase of her wartime career came in 1944 when she volunteered to travel abroad for Ensa, the organisation set up to provide entertainment for the forces. The five-month trip took in concerts and hospital visits in the Middle East, India and finally Burma. The weeks she spent with troops in this relatively forgotten theatre of war remained with her for the rest of her life and she became the most ardent advocate for the remembrance and care of veterans of the 14th Army who fought in Burma.

In the changing conditions of peacetime, Lynn faced competition from new and sometimes younger rivals, such as Anne Shelton, Dorothy Squires, Eve Boswell and Petula Clark, all of whom made rival recordings of new songs in the 50s. She remained in demand for variety theatre tours and starred in the long-running London Laughs with the comedians Jimmy Edwards and Tony Hancock in 1952-54. But she was not offered work by BBC radio for several years because in 1949 the head of variety, Michael Standing, told her that “sob stuff” was outmoded. A few years later he was quoted as “still looking for the new Vera Lynn”.

In the meantime, Lynn made broadcasts for Radio Luxembourg. Several of these shows were recorded with an audience of RAF servicemen, who occasionally joined in the chorus of a song. That combination was repeated on bestselling Decca recordings, billed as “Vera Lynn with Soldiers and Airmen of HM Forces”. Among these were Auf Wiederseh’n Sweetheart, The Homing Waltz and The Windsor Waltz. The first of these inspired the title of the 80s sitcom Auf Wiedersehen, Pet. The disc was listed in the first published British hit parade in the New Musical Express in 1952 and topped the American charts, selling over a million copies there. Her biggest hit in Britain was My Son, My Son, co-written by the trumpeter Eddie Calvert, which reached No 1 in 1954.

With the arrival of commercial broadcasting in 1955, Lynn was given her first television series and in the following year the BBC invited her back with a two-year exclusive contract to include both television and radio appearances.

Unlike some of her contemporaries’ careers, Lynn’s continued to prosper despite the arrival of rock’n’roll and, later, the Beatles. During the 60s and 70s, she made frequent concert performances, recordings and television appearances. For many of these, including two nostalgic LPs of “Hits of the Blitz”, she reprised her wartime and 50s favourites, but she was briefly persuaded to record contemporary songs such as Lennon and McCartney’s Fool on the Hill and Jimmy Webb’s By the Time I Get to Phoenix, and to make an album in Nashville. Several CD reissues of her recordings have been made, including the No 1 album We’ll Meet Again: The Very Best of Vera Lynn (2009) and Unforgettable (2010), which included three previously unreleased tracks from the 40s.

https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/T5C4meGkNyc?wmode=opaque&feature=oembedVera Lynn sings We’ll Meet Again in the musical film of the same name (1943)

A prominent feature of Lynn’s career was her commitment to charities, including several that support ex-service personnel and others concerned with polio, breast cancer, blindness and cerebral palsy. A trust for children with cerebral palsy was set up in her name and continues to support a school near Lynn’s home in West Sussex.

In 1995, Lynn made her final official public performance at a VE Day anniversary event at Hyde Park. Even afterwards, she attended second world war commemorations, sometimes giving a speech, as at the 2005 VE Day event at which Katherine Jenkins, Lynn’s preferred successor as the forces’ sweetheart, performed We’ll Meet Again. Jenkins later recorded the song to add to Lynn’s original. Their virtual duet was included on the 2014 CD release, Vera Lynn – National Treasure.

Three days before her 100th birthday, she released Vera Lynn 100, featuring new orchestrations of her best-known songs alongside her original vocals. She was joined on the album by the British singers Aled Jones, Alexander Armstrong and Alfie Boe. Her birthday was also marked with a projection of her face on to the white cliffs of Dover. The album went to No 3, making her the first centenarian to enter the UK charts, and charted again in May this year following the 75th anniversary celebrations of VE Day, which were also marked by a duet between Jenkins and a hologram of Lynn at the Royal Albert Hall, and the re-release of We’ll Meet Again.

The Queen invoked the spirit of the song as she addressed a nation in coronavirus lockdown in April, assuring Britons “We will meet again”, and echoing Lynn’s own message to fans in March: “In these uncertain times, I am taken back to my time during World War II, when we all pulled together and looked after each other. It is this spirit that we all need to find again to weather the storm of the coronavirus.”

Harry died in 1998. She is survived by her daughter, Virginia.

Vera Lynn (Vera Margaret Welch), singer, born 20 March 1917; died 18 June 2020

Dave Laing died in 2019