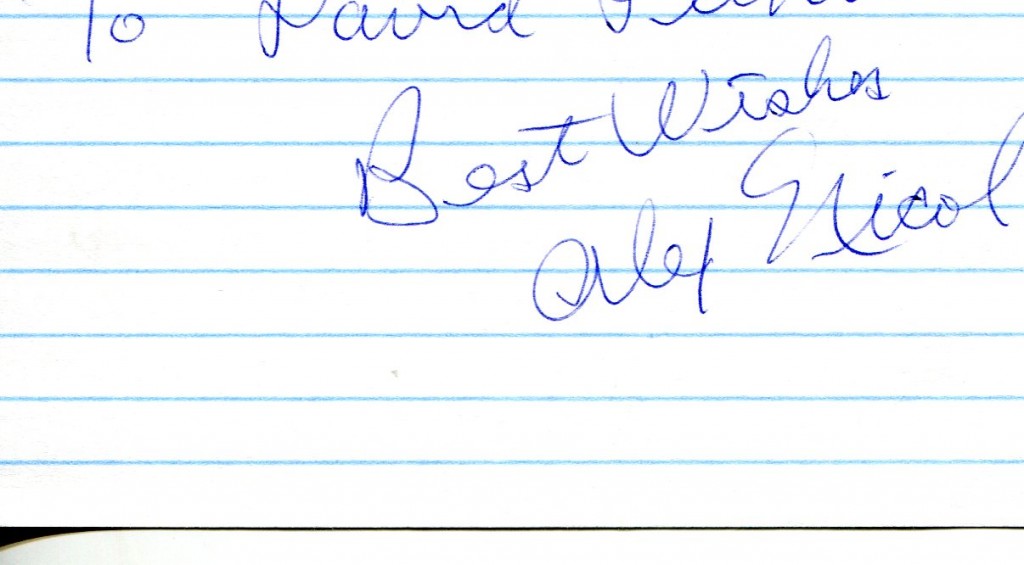

Alex Nicol obituary in “The Independent” in 2001.

His “Independent” obituary:

Alexander Livingston Nicol, actor: born Ossining, New York 20 January 1916; married 1948 Jean Fleming (two sons, one daughter); died Montecito, California 29 July 2001.

The actor Alex Nicol played occasional leading roles on screen, for which his fair-haired good looks and sturdy physique seemed to qualify him, and when, on stage, he played Brick in Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Williams wrote that Nicol captured the part exactly as he had conceived it. But it was as a character actor that he spent most of his career, with a particular flair for portraying villains with a weak or pathological nature, epitomised by his fine performance in the western The Man From Laramie. He also directed several films, and appeared frequently on television.

He was born Alexander Livingston Nicol Jnr, in Ossining, New York, in 1916, though when his movie career started 34 years later he was astute enough to adjust the year to 1919. “I was a little older than some of the other people under contract so I thought, ‘Well, I’ll cure that right now’,” he later confessed. His father was a prison warden at Sing Sing and his mother a head matron at a women’s detention centre, so it was ironic that he studied at the Fagin School of Dramatic Arts before joining Maurice Evans’ theatrical company, with whom he made his Broadway début with a walk-on in Henry IV Part One (1939).

His career was interrupted by a five-year spell in the army, in which he served with the National Guard and Cavalry Unit and attained the rank of Technical Sergeant, after which he enrolled at the Actor’s Studio. “With Evans, I was the least important member of the cast. I was learning my craft in public. Then it all got put on hold until the end of the war, after which I became one of the original members of the Actor’s Studio. Marty Ritt and Elia Kazan were running the Studio then.” Nicol returned to Broadway in a revival of Clifford Odets’ potent pro-union dramaWaiting for Lefty (1946), followed by roles in Sundown (1948) and Forward the Heart (1948).

He was part of the original cast of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s classic musical South Pacific (1949), playing one of the marines, but after a few weeks in the show he successfully auditioned to replace Ralph Meeker as the sailor Mannion in the hit playMister Roberts, and was also made understudy to the play’s star Henry Fonda:

But I never made it! He never missed a performance! Henry’s wife at the time killed herself during the run of the show and he still didn’t miss the performance. We were one minute from curtain time when Fonda walked in, in costume, and he just walked right out, hit his mark and played the performance as though nothing had happened.

(Fonda’s proprietorial approach to the part became legendary. After he heard that James Stewart had expressed a willingness to replace him when he left the show, he stayed with it for the entire three-year Broadway run and subsequent tour, a total of nearly 1,700 performances.)

While acting in Mister Roberts, Nicol was seen by the Universal director George Sherman, who was in New York to prepare The Sleeping City (1950), to be filmed entirely on location. He cast Nicol as a young doctor who commits suicide after stealing drugs to pay off gambling debts. “It was a very showy, flashy part,” said the actor. “The whole thing was shot in a really grim, Neo-Realist style.” Nicol was given a contract by Universal, and Sherman also directed his second film, Tomahawk (1951), in which he played a cavalry officer with a hatred of Indians.

Roles as a prisoner-of-war in Target Unknown (1951) and a trainee pilot in Air Cadet (1951) preceded Nicol’s first major part, co-starring with Frank Sinatra and Shelley Winters in the musical drama Meet Danny Wilson (1952). Winters wrote, “Alex Nicol was a very mature, menschie guy (for an actor). He was great fun and lovely to work with.” As the lifelong protector and best friend of a bumptious singer (Sinatra), Nicol handled a difficult part with conviction. However, in his next film he was cast as a heavy again, causing Loretta Young to be wrongly sent to prison, then blackmailing her on her release, in Because of You (1952), and he was a troublesome sergeant in Red Ball Express (1952), directed by Budd Boetticher. “A talented guy,” said Nicol, “but he was the only director in my whole career whom I couldn’t get along with. He had a very big ego.”

Nicol’s first starring role was opposite Maureen O’Hara in The Redhead from Wyoming (1953), a lacklustre western directed by Lee Sholem:

“Roll ‘Em Sholem” they used to call him. All he would say before every scene was “Roll ‘Em!” And then when you got to the end of the scene he’d say “Cut!” and then he’d look at the script clerk and say, “Did they say all the words?”, and if she said “Yes” then that was it. When the picture was over I went to the front office at Universal and asked to be released from my contract. They thought I was crazy. But I thought, “If this is my big break, then I’m not going very far.”

As a freelance, Nicol was directed by the former Actor’s Studio teacher Daniel Mann in About Mrs Leslie (1953) starring Shirley Booth and Robert Ryan. “The script wasn’t as strong as it might have been, but it was a great cast.” He returned to Universal (at a much larger fee than he had been getting as a contract player) to appear in two George Sherman films, Lone Hand (1953) andDawn at Socorro (1954). “George was really a fan of mine and always wanted to work with me, so he kept bringing me back to Universal.” Nicol then made three films in England, most notably Ken Hughes’s The House Across the Lake (1954), in which he was a failed novelist who becomes involved in crime:

It was a great script, and Sidney James, a wonderful actor, was in it, along with Hillary Brooke. Eventually I got back to the United States and I was glad to come back. Those British pictures kept me working, but they were really fast, really cheaply budgeted.

Anthony Mann directed Nicol in his role as a pilot in Strategic Air Command (1955), and it was Mann who then gave the actor his best- remembered role, that of the weak, psychopathic son of a patriarch rancher (Donald Crisp) in the darkly compelling western (allegedly inspired by King Lear) The Man from Laramie (1955), starring James Stewart. “Tony was very creative, great to work with, and I admired him.”

Jacques Tourneur’s Great Day in the Morning (1956) was another superior western, but it became apparent to Nicol that his Hollywood career was not progressing, and in 1956 he returned to Broadway to replace Ben Gazzara in the leading role of Brick, the former athlete who has become a guilt-ridden alcoholic in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. It brought the accolade from Williams and when the Broadway run ended Nicol starred in the tour.

He had the chance to create a role on stage when he was starred with Shelley Winters in the play Saturday Night Kid (1958), but it closed in Philadelphia without reaching Broadway and he returned to Hollywood where he made his first film as a director,The Screaming Skull (1958), in which he also starred:

I wasn’t doing the kind of films as an actor that I wanted to do, so I thought, “Well, I’ll try directing.” We shot the picture in six weeks and it did very well, so I was happy with that.

Nicol travelled to Italy when the director Martin Ritt gave him a role in Five Branded Women (1959), and while there he was offered parts in other European movies, so he settled there for two years with his family. (In 1948 he married the actress Jean Fleming and they had three children.)

We lived in Rome; God, it was beautiful. We did a lot of films very quickly, with backing from Italian and Yugoslavian finance sources. It was one of the happiest times of my life.

Returning to the United States in 1961, he played Paul Anka’s father in the thriller Look in Any Window (1961), then produced and directed a war film in Rome, Then There Were Three (1961), in which he co-starred with the American expatriate Frank Latimore. Subsequent acting roles included two spaghetti westerns, The Savage Guns (1962) and Gunfighters of the Casa Grande (1964), and Roger Corman’s gangster movie based on the life of criminal Ma Barker, Bloody Mama (1969), in which Nicol played the husband of Shelley Winters.

Nicol had made his television début in 1949 in Lux Video Theater. Other shows included Studio One, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Twilight Zone and The FBI, and he directed episodes of Daniel Boone and The Wild Wild West. The last film in which he acted was A*P*E (1976), an independent movie made by a friend of the actor.

In 1996 Nicol told the interviewer Wheeler Winston Dixon,

Starting in the 1960s, I started putting money aside to buy a couple of apartment houses, which was the smartest move I ever made because I’m living on that money now. I like it here in Santa Barbara, living in a rather elegant area. I’m winding up pretty much the way I wanted to.

Tom Vallance