Joseph Tomelty was a gifted actor and writer who hailed from Portaferry in Co. Down. In 1938 he became part of the Northern Ireland Players. He wrote many novels and plays but also began a career as a reliable character actor. His films of note include “Odd Man Out”, “The Gentle Gunman” and “A Kid for Two Farthings”. He died in 1995.

“The Independent” obituary:

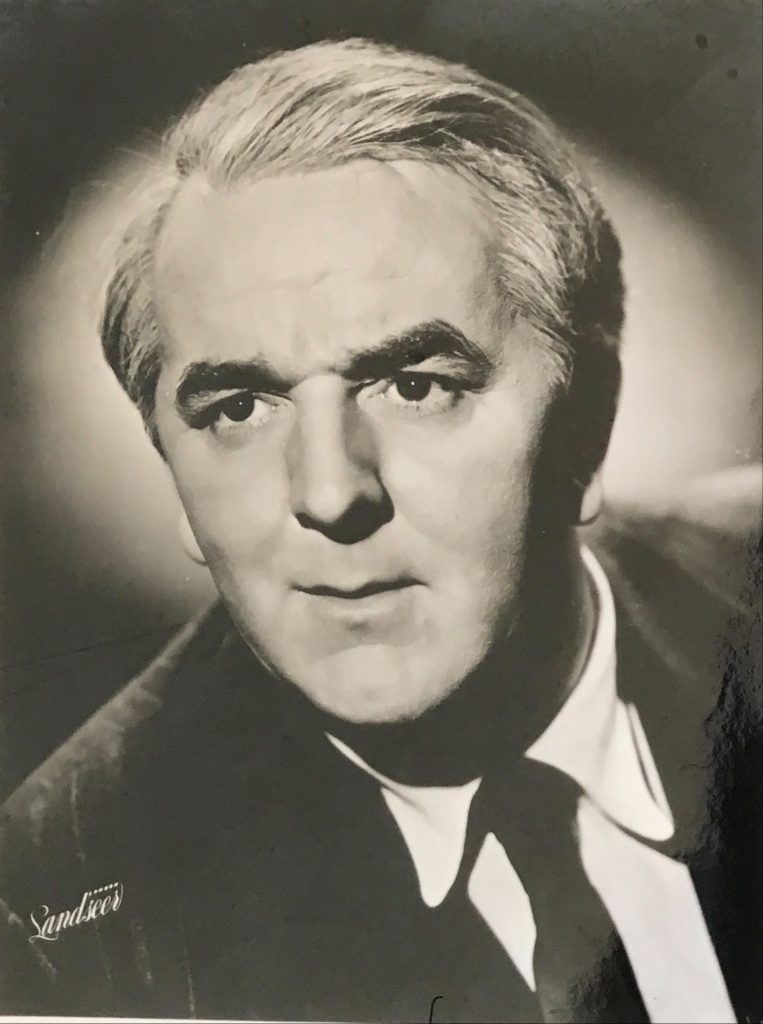

As an actor, playwright, novelist, short-story writer and theatre manager, over a professional career of only 16 years, Tomelty achieved an enviable success which crossed the borders of popular and critical acclaim, burning the image of his rugged, sensitive features, and distinctive white hair, across the sectarian divide into the common mythology of his chosen city of Belfast.

Tomelty was born in 1911 in Portaferry, Co Down – a small fishing village on the east coast of Ulster, and the setting for his most effective works. His father, James Tomelty, was nicknamed “Rollicking” because of his skill with the fiddle, and music became one of the strongest influences in the playwright’s work – three of his plays take their titles from traditional songs: The Singing Bird (1948), Down the Heather Glen (1953) and The Drunken Sailor (1954).

He left the local primary school, Ballyphilip, at the age of 12 and was apprenticed to his father’s trade as a housepainter. This involved classes at the Belfast Tech, and living in digs on the Catholic Lower Falls gave a peculiar authenticity to his second novel, The Apprentice, which follows the young Frankie Price out of a harrowing childhood into a chance of life. It remains a vivid and painful document of poverty of spirit and individual resilience; and the ghost of Frankie Price has haunted many of the novels and plays to come out of the north since.

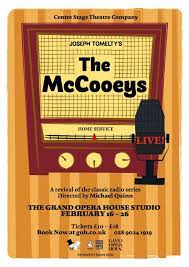

At this time too Tomelty met Min Milligan, who was to create many of his most memorable characters, including Aunt Sarah in his ground-breaking BBC radio series The McCooeys. He married her daughter Lena in 1942 and they had two daughters, both now in the theatre profession – Roma and Frances.

Tomelty had already been instrumental in forming the Group Theatre in Belfast in 1940 and had started writing the plays for St Peter’s Players and subsequently the Group, which were to establish him at the very heart of northern culture after the war – Barnum was Right (1938), Right Again, Barnum (1943) and the controversial The End House, premiered at the Abbey in 1944 when northern theatres wouldn’t touch it.

Association with what was known as “the Tomelty clique” – actors, painters and writers, including the young Brian Moore, who gathered at Campbell’s cafe in the city centre – was a liability in the terms of the Unionist establishments at the BBC and in government. The End House, dealing with a Catholic family under the Special Powers Act, was simply not produced, even at Tomelty’s own theatre, the Group. It received its Northern Ireland professional premiere only in 1993 as a highlight of the Belfast Festival at Queen’s.

It is here that the extent of Tomelty’s commitment to and investment in Belfast is apparent. At the same time as pursuing a successful acting career in British and Hollywood films (like Odd Man Out, Bhowani Junction and Moby Dick), writing plays as diverse as All Souls’ Night (1948) and Is the Priest at Home? (1954), and his first novel, Red is the Point Light (1948), he was providing 6,000-word scripts for each weekly episode of The McCooeys – a total in the region of 800,000 words over seven years. It is hard to overestimate the impact of that series. In his hands, an intended middle-class drama became a narrative of working-class life which invented “Belfast” as a popularly conceived city, and so influenced a generation that the death of its author has struck thousands as a personal loss.

If he chose Belfast because Belfast meant life and street comedy – an interesting thought – it was otherwise in his two most enduring works. Red is the Port Light deals with superstition, oppression and murder on the east coast of Ulster; it is beautiful, black and bleak. All Souls’ Night is a relentless tragedy of human greed and repression, a classic Irish drama which reaches its several moments of greatness with deep emotional power. It returns Tomelty to the obsessive sadness of his east coast and draws out an awesome bitterness tempered by an achieved poetic vision. There are few Irish plays to match it. Which makes all the more poignant the vicissitudes of his own life. During the run of Is the Priest at Home? in 1955, while filming in England, he was injured in a car crash. He was 43. He was unable afterwards to resume the many commitments of his career.

But it was by no means the end. He was awarded an MA for services to theatre by Queen’s University, Belfast, in 1956, the first actor to be so honoured; in the 1980s, his novels were reprinted by Blackstaff Press in Belfast; in 1991, the Arts Council of Northern Ireland commissioned a bronze bust to celebrate his 80th birthday; in 1993, an edition of his plays introduced his work to a new generation; and his plays continue to be produced in both amateur and professional theatre.

At his funeral, which began in the splendour of St Peter’s Cathedral, in Belfast, and ended on a windy hill in Portaferry, the people of the city turned out to mark his passing. A piper playing “The Singing Bird” to accompany the burial in his home townland of Ballyphilip marked also the end of an era in northern Irish letters.

Damian Smyth

Joseph Tomelty, actor, playwright, novelist, theatre manager: born Portaferry, Co Down 5 March 1911; married 1942 Lena Milligan (two daughters); died Belfast 7 June 1995.

Dictionary of Irish Biography:

Contributed by

Tomelty, Joseph (1911–95), actor and playwright, was born 12 March 1911 in Portaferry, Co. Down, son of James Tomelty, house painter and keen traditional musician, and Mary Tomelty (née Drumgoole). Apprenticed to his father’s trade from the local school Ballyphilip at the age of 12, he moved to Belfast to finish his training and attended classes at the city’s technical college, where an English teacher, a Mr Tipping, encouraged him to write. Employed in the Harland & Wolff shipyards, he lived in lodgings on the Lower Falls road and began to act in 1937 with an amateur company, the St Peter’s Players. They produced the first of his thirteen plays, ‘Barnum was right’ (1938), which was also broadcast on BBC radio in December that year. With others in his company, he helped found the Northern Ireland Players in the winter of 1938–9. They staged his play again in the Belfast Empire Variety Theatre in June 1939, with great commercial success. In 1940 the Players joined the Jewish Institute Dramatic Society – under the direction of Harold Goldblatt (qv) – and the Ulster Theatre to form the Group Theatre, resident in the Ulster Minor Hall in Belfast’s Bedford St. Tomelty was an actor and the general manager of the company from 1941 to 1952; he was also booking clerk, usher, doorman, and cleaner. His plays brought the vernacular life of the north to the stage; ‘The end house’ (1944) is a protest against the special powers act, with the idealist republican Seamus MacAstocker killed by police who think he is trying to escape custody. It was first performed at the Abbey Theatre, Dublin, on 28 August 1944. The audience, unsure of the play’s relevance, reacted to it as comedy; to add further insult, newspaper critics felt that it was not funny enough. Tomelty avoided explicit political commentary thereafter. ‘All souls’ night’ (1948) is a haunting tragedy first performed by the Group Theatre in September 1948. Its author played the lead role of John Quinn, the fisherman who loses two sons to the sea.

Red is the port light (1948) was his first novel and is the psychological drama of another sailor, Stephen Durnan, who survives a shipwreck only to marry the widow of the foundered vessel’s captain. A dark tale that ends in murder, it is entirely opposite to the radio serial ‘The McCooeys’ (1948–54), which he wrote and acted in for the BBC Northern Ireland Home Service. Requiring a script of 6,000 words every week, ‘The McCooeys’ played to huge audiences; Sam Hanna Bell (qv) remembered walking through the Co. Antrim village of Waterfoot on a summer evening and following that week’s story from house to house through open windows. Tomelty played the central role of Bobby Greer, the grocer who tells the family’s story. The apprentice(1953) is a Bildungsroman that concerns the growth of Francis Price, who shares the author’s trade – painting – and his stutter. Well-written, the novel is lyric and erotic; it brings the young urbanite Price to an appreciation of a wider life beyond the constricted Belfast he first knew. Tomelty left the Group theatre in 1951 to take the part of John Fibbs in a Tyrone Guthrie (qv) production of ‘The passing day’ (1936), by George Shiels (qv), for the Festival of Britain. The director David Lean noticed him, and a film career that had started with his role as the cabbie in Odd man out (1947) prospered. He played Doctor Brannigan in The gentle gunman (1954) with Dirk Bogarde and John Mills, and Dooley in Happy ever after (1954) with David Niven. Disaster struck when he took screen tests in 1954 to star with Ava Gardner in Bhowani junction. He suffered near-fatal injuries in a car crash that left him unconscious for weeks and unable consequently to write or act, with rare exceptions. But his earlier work did have continuing influence; John B. Keane (qv) wrote ‘Sive’ (1959) after seeing a production of ‘All souls’ night’ (1948) by the Listowel Drama Group in the late 1950s.

He lived in retirement after his accident for the remaining half of his life and died on 7 June 1995 in Belfast; he is buried in St Patrick’s cemetery, Ballyphilip. Contemporaries remembered him as a good-humoured, generous man whose career was prematurely ended. He married (1942) Lena Milligan and left two daughters. Recipient of an honorary MA from QUB in 1956 for his services to acting, he was the subject of a bronze bust by Carolyn Mulholland, commissioned by the Arts Council of Northern Ireland, in 1991.

Sources

Irish Booklore, i, no. 1 (Jan. 1971), 106; no. 2 (Aug. 1971), 226–34; Sam Hanna Bell, The theatre in Ulster (1972); Christopher Fitz-Simon, The Irish theatre (1983); Linen Hall Review, autumn 1984; D. E. S. Maxwell, A critical history of modern Irish drama 1891–1980 (1984); Hagal Mengel, Sam Thompson and modern drama in Ulster (1986); Joseph Tomelty, All souls night and other plays, ed. Damian Smyth (1993); Edna Longley, The living stream (1994); Ir. Independent, Ir. Times, 8 June 1995; Belfast News Letter, 8, 9 June 1995; Kevin Rockett, The Irish filmography (1996); Robert Welch, The Abbey Theatre 1899–1999 (1999); Gillian McIntosh, The force of culture(1999