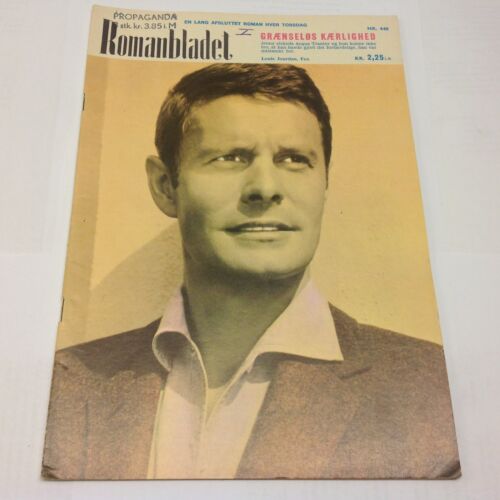

Louis Jourdan obituary in “The Independent”.

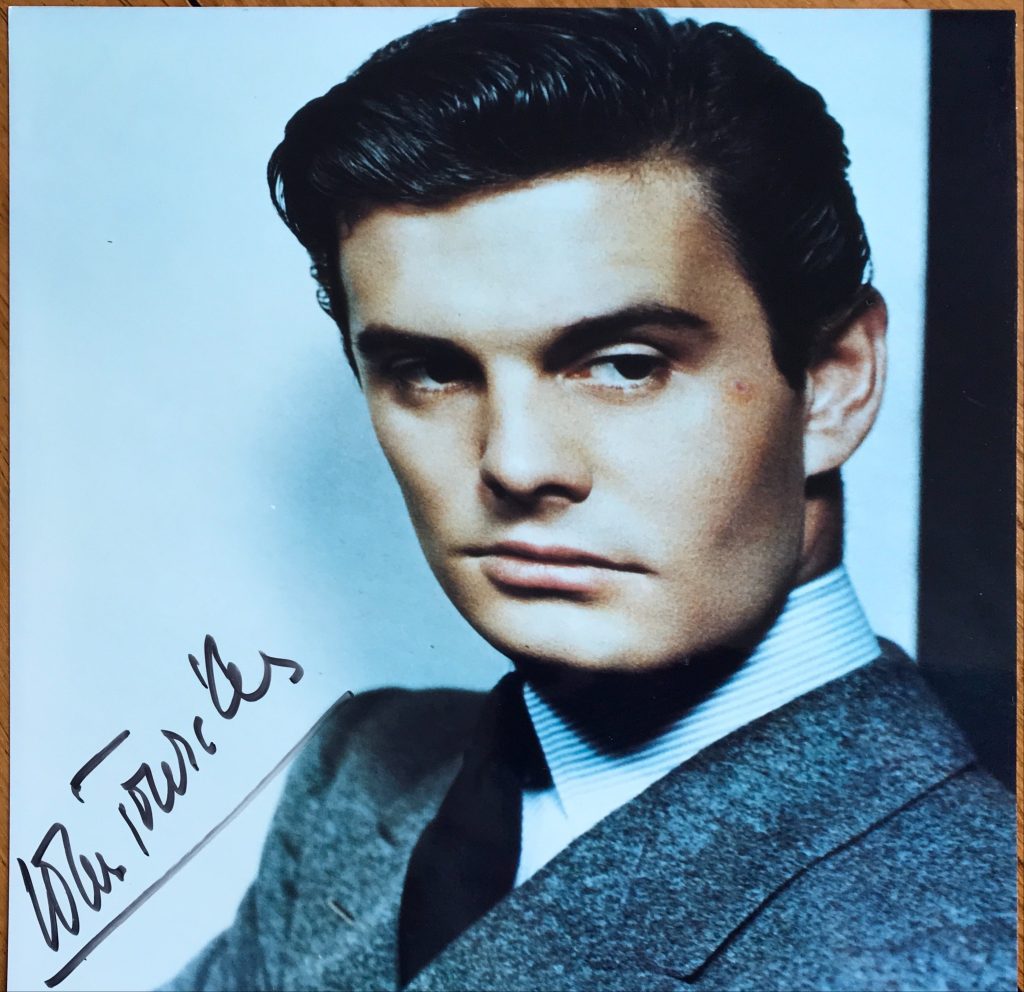

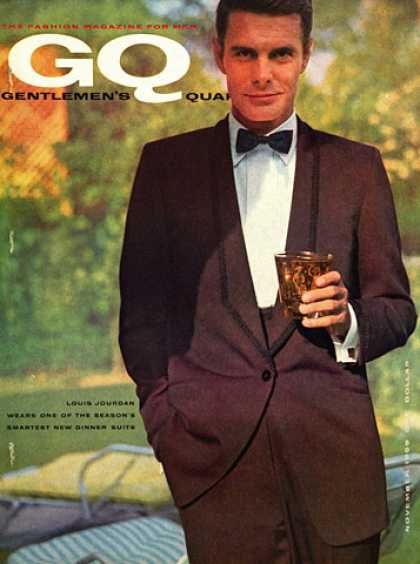

Good looks can be a mixed blessing for an actor. In the case of Louis Jourdan, the romantic star who died on Saint Valentine’s Day aged 93, they guaranteed him a career both in his native France and in Hollywood, but rarely in roles that moved him out of an audience’s comfort zone. A handsome devil to say the least, he was the absolute epitome of the suave, debonair, seductive Frenchman. The camera adored him, a creature of immaculate appearance and masculine finesse.

It was his role as the bon vivant enchanted by Leslie Caron’s flibbertigibbet debutante in Gigi (1958) that made him an international star. The film won nine Oscars and made Jourdan, who sang the title number, Hollywood’s favourite Frenchman. He was cast by producer Arthur Freed when Dirk Bogarde proved unavailable, Freed having delighted in Jourdan’s performance in Three Coins in the Fountain (1954) as the louche Prince Dino, a notorious womaniser whose girlfriends become known as “Venice girls” after he takes them to Venice for romantic trysts.

Born in Marseille in 1921 as Louis Robert Gendre, the son of hotelier Henry Gendre, he rubbed shoulders with the glitterati from an early age when his father ran a seaside hotel in Cannes and assisted in the running of an early incarnation of the city’s film festival. He was encouraged by the visiting stars, and although his father’s career moved the family to Turkey and England, the latter destination provided an excellent opportunity to master the English language. Back in France, he studied acting under René Simon at the École Dramatique, and upon graduating, took his mother’s maiden name of Jourdan.

He was spotted on stage in Paris by the screenwriter and director Marc Allégret, a prodigious talent-spotter who could also claim to have discovered Gérard Philipe, Roger Vadim and Michèle Morgan. Allégret gave him work as an assistant camera operator on a drama within a drama school, Entrée des Artistes (The Curtain Rises), in 1938, as preparation for his movie debut the following year in another story of actors finding the line between work and play blurring, Le Corsaire (The Pirate). Adapted from a play by Marcel Achard, the film offered Jourdan the chance to act opposite Charles Boyer, a French star in Hollywood who Jourdan would go on to emulate. It was a hotly anticipated project, but shooting was halted after a month as France mobilised for war, and the film was never completed.

He did get to act opposite another major star, albeit a fading one, Ramon Novarro, in his eventual film debut, La Comédie du Bonheur (The Comedy of Happiness) in 1940, before war put his career on hold.

During the war, his father was a prisoner of the Gestapo, while Jourdan and his brother were active members of the Resistance, printing and distributing leaflets. He refused to appear in films propagandising Philippe Pétain’s collaborationist government, a stand which made him rightly cherished when the French film industry rebuilt itself in the post-war years.

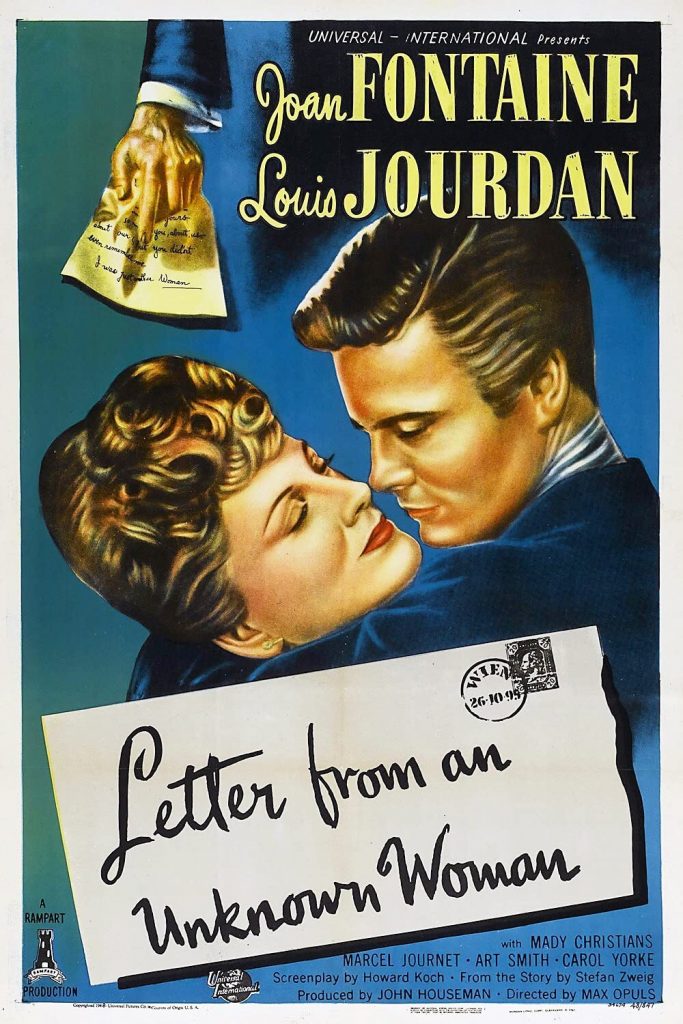

He left for Hollywood in 1946 at the invitation of David O Selznick, and made a good first impression as a man of mystery in the courtroom drama The Paradine Case (1947), a costly affair directed by Hitchcock and starring Gregory Peck. No aspiring movie star could have wished for better company to ride into town with, although the film turned out to be a disappointment. His much better second Hollywood film got him his name above the title and allowed him to add depth to another smouldering lothario: Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948), co-starring Joan Fontaine, is an affecting study of unrequited love that remains a powerful watch today. It was the work of another European in Hollywood, director Max Ophüls, which perhaps explains the skillful dodging of tuppeny novelette melodrama for delicate emotional exploration.

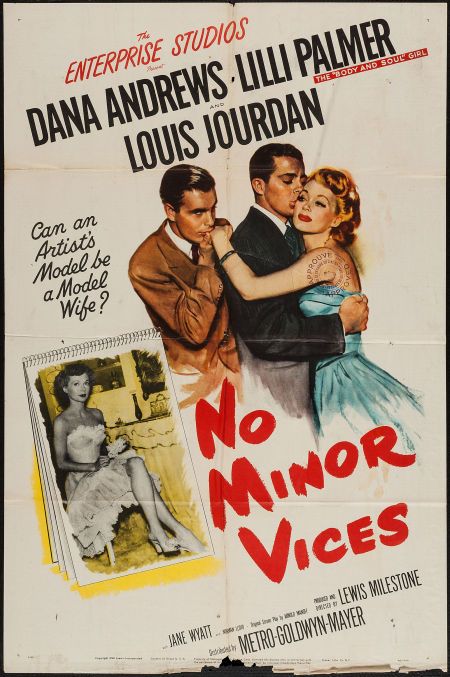

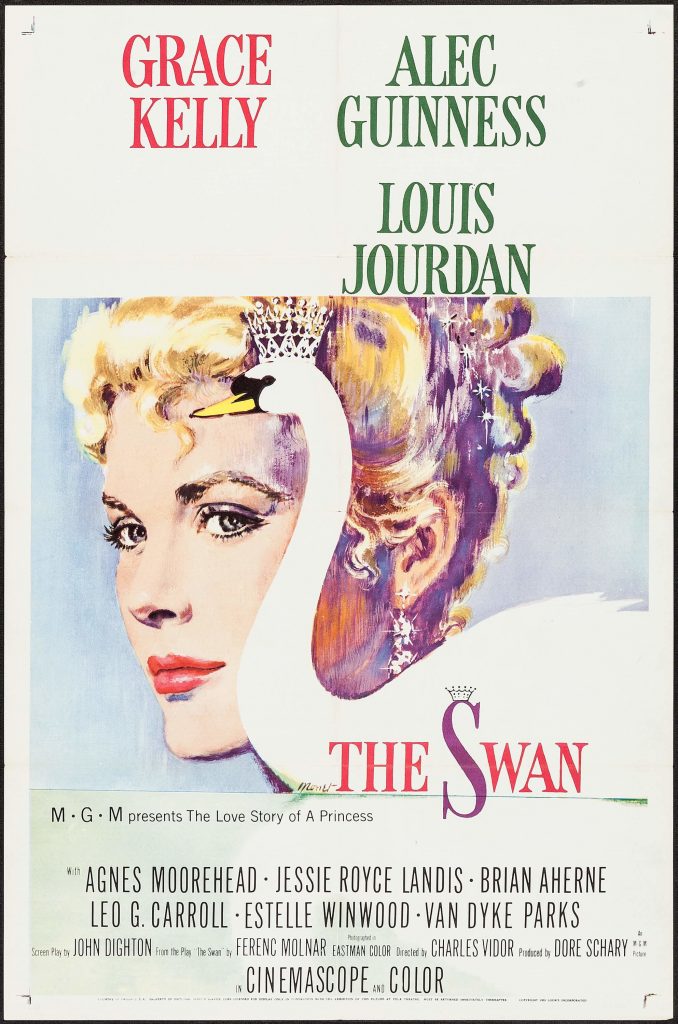

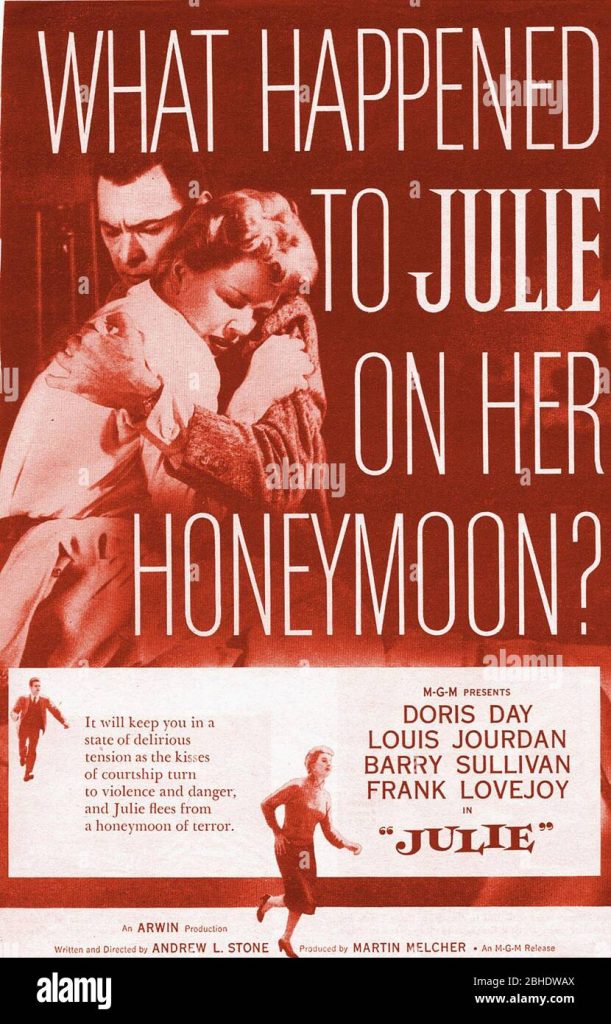

Louis Jourdan in ‘Gigi’ (Getty)He began to sense the perils of typecasting when appearing as the lover of adulterous Jennifer Jones in Vincente Minnelli’s Madame Bovary (1949), and in an attempt to break free of such roles, returned to France briefly, where he continued to play lovers, but of a slightly different style: the philandering was strictly for fun in Rue de l’Estrapade (1953) for instance, and his features lent themselves well to villainous roles when he played Doris Day’s psychotic husband in Julie (1956). However, he was by his own admission, “a star without a hit” until he surrendered to Three Coins in the Fountain (1954) and then Gigi (1958), which overwhelmed his attempts to break free of light romantic leads.

His Gigi co-star, Leslie Caron, remembered that he was “one of the handsomest men in Hollywood, but not comfortable with his image”, a predicament he shared with the aforementioned Dirk Bogarde. He regularly claimed he was “Hollywood’s French cliché”, in parts that involved “mostly cooing in a woman’s ear”, Gigi in particular making him world famous as “a colourless leading man”.

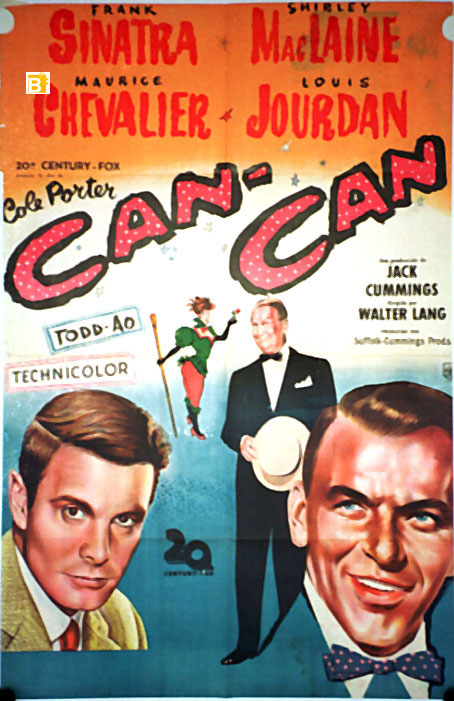

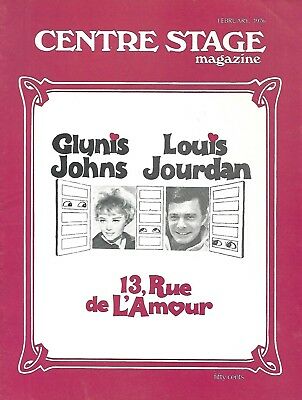

He remained a bankable star in Hollywood following the success of Gigi: he followed it up with another musical, Can-Can (1960), co-starring Frank Sinatra and Shirley Maclaine, but his most interesting work was generally to be found elsewhere. His Broadway debut, in the lead role for the Billy Rose stage adaptation of André Gide’s novel The Immoralist, at the Royale Theatre in 1954, was a bold undertaking: he not only played a gay man, but worked in between a brittle James Dean and his then lover, the intense Geraldine Page. The performance won him a Donaldson Award for Best Actor.

He made his American television debut starring in the detective series Paris Precinct for ABC in 1955, but it was a medium he fared better with in Britain, where he was occasionally cast much more imaginatively – on one occasion as the persecuting husband in Gaslight, opposite Margaret Leighton, for ITV in 1960, and for Lew Grade in 1975, playing De Villefort to Richard Chamberlain’s Count of Monte Cristo.

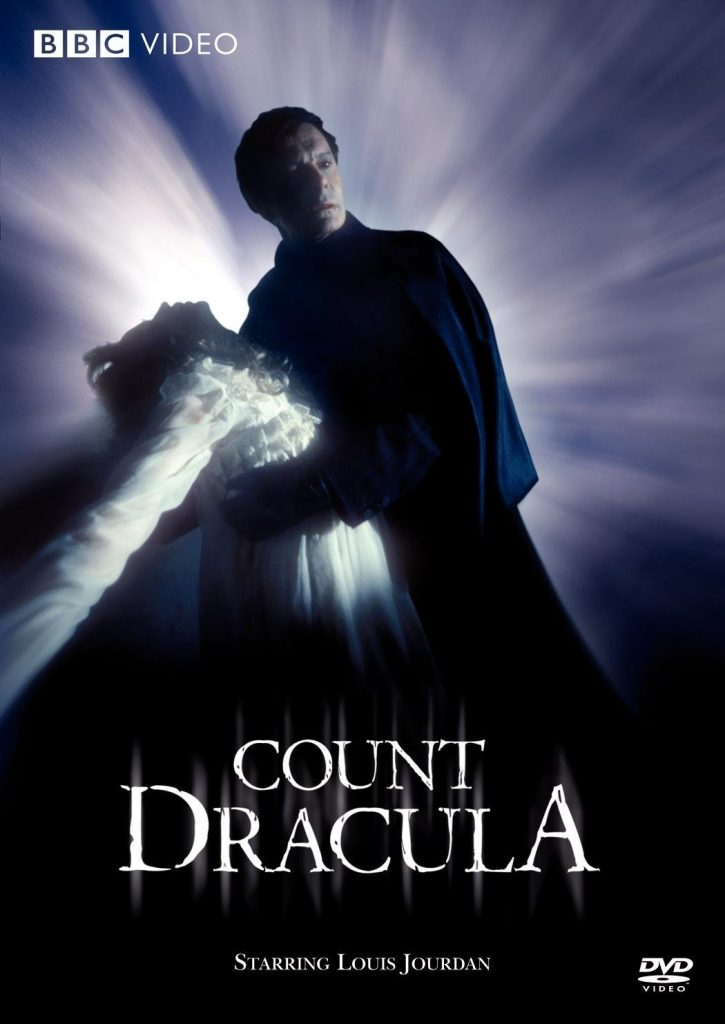

One of the most interesting moments in his career came when Philip Saville cast him as the lead in Count Dracula (1977), a weighty BBC dramatisation that remains one of the most faithful imaginings of the source material, coming just after Hammer Films had given up the ghost. Jourdan’s casting surprised the critics, but, speaking to the Radio Times in 1977, Saville explained that he saw Dracula as “a romantic, sexually dashing anti-hero in the tradition of those figures usually dreamed up by women… Rochester, Heathcliff… figures that can overpower a strong heroine, inhuman figures that can’t be civilised.” Ahead of the game in finding romanticism in vampirism, the drama occasionally lacks bite – but Jourdan remains one of the most interesting and original Draculas in screen history.

He was the best thing in Octopussy (1983), an otherwise lousy Bond film which even lacked a memorable theme song, and bowed out with a similarly suave villain in Peter Yates’s Year of the Comet in 1992, the year he retired. Sadly, few of the roles in his final years are much to speak of.

Although his career was plentiful, it was hamstrung by poor timing and monotonous casting. Nevertheless, he was always a pleasure to watch, a naturally appealing performer. Despite his lothario image, he remained married to his childhood sweetheart, Berthe (known by the nickname Quique) for 67 years, until her death last year. They had one son, who fell victim to drug addiction and died in 1981.

Whenever he spoke in interviews of his enduring marriage, his seductive but sincere voice and passionate conviction could, in Ophelia’s words, move the stoniest breast alive, and reminded one that he was a star of the kind that they just don’t make anymore.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.