Marlon Brando obituary in “The Guardian” in 2004.

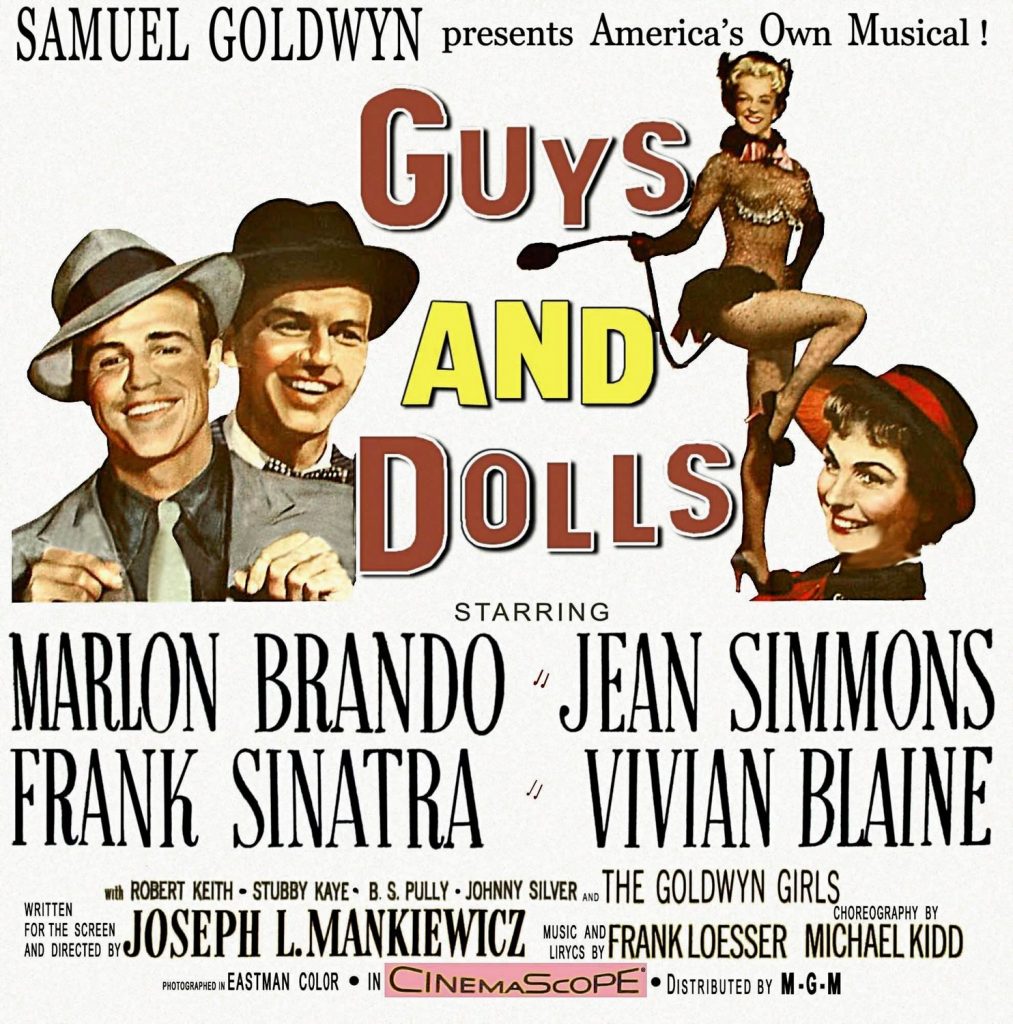

Marlon Brando is regarded as one of the best cinema actors to grace the screen. He was born in 1924 in Omaha, Nebraska. His sister Jocelyn had commenced an acting career. Marlon went to Broadway in his late teens. He became the toast of Broadway for his part as Stanley Kowaski in Tennessee William’s “A Streetcar Named Desire”. He made his film debut in Fred Zinnemann in “The Men” in 1950. He repeated his Broadway performance in the film version of “Streetcar” in 1951 with Vivien Leigh. He won the Oscar twice for “On the Waterfront” and for “The Godfather”. His other fine performances include “Guys and Dolls”, “Desiree”and “Sayonara”. Marlon Brando died in 2004.

“Guardian” obituary:

He was only an actor, and as he pointed out actors are no more than dishonest entertainers, frauds, pretenders, liars – he could be relentlessly hard on himself. But was it then any defence that he acted so seldom, that he had deserted the stage he had himself brought to life, or that he had come to regard movies with the hurt feelings of a Kong, hiding in his lair, unwilling to make a cheap spectacle of himself for those exploiting showmen? Why trust acting or films, he sometimes said, for these things emerge from the pit of our corruption. Not that he had made himself, as an alternative, a model of quieter, domestic virtues. By his own gloating, but tortured, confession, he was a career womaniser, a glum joke as a husband, and sometimes pitiful as a father. Anything else? Why, yes, of course, he was a hulk, a wreck of obesity and self-indulgence, a hideously fat man – he who once had been so beautiful he altered our idea of maleness.

It can be no surprise that, at the age of 80, Marlon Brando is dead. Rather, it must speak to his will and need that he lived so long, so out of shape and humour. And he was also so resentful of the world, and so scornful of himself, that it is hard to measure lost happiness. The man who published his autobiography Songs My Mother Taught Me, in 1994, was already cynical to the point of nihilism, a tease and a trickster, yet always most mocking of himself. To read that book was to be disturbed at how little he liked himself, no matter the conventional armour of vanity in a grand actor. He could be very vain and very foolish – in part because of the opening they provided for self-loathing later. He did his book for money, and then he ranted against people who were so mercenary. But he needed money for his broken family – and he had never made or kept as much as lesser actors – one son in jail, another child on her way to suicide. A godfather in legend, he was confused in life. You could hear the howls of grief between the lines – yet he had denied himself, and us, a Lear. And Falstaff, and Vanya, and so on.

Yet he was the American actor of modern times, and of the second half of the 20th century, someone who was regularly placed in that small circle of the finest actors, the most potent and dangerous actors who could take a role and their audience into emotional territory that no one had anticipated. What was most remarkable about Brando was that unquestioned eminence rested on so few films and on just one historic stage performance.

Born in Omaha, Nebraska – the state that produced Montgomery Clift, Henry Fonda and Fred Astaire – he was only 23 when he brought Stanley Kowalski to life in A Streetcar Named Desire in 1947. It had not been a comfortable life. He was the child of two drunks, the father domineering, miserly, a womaniser but unloving, the mother creative but weak, broken and helpless. He had grown up feeling unloved and untrusting, hating authority, strong men and needy women. Yet it was far from the worst life imaginable, and it would be wrong to see the youth as wounded. There was, from the outset, a rebelliousness, an ego and an intricate self-pity determined to be wronged. And in that wronging he found energy.

Other people could only fall in with their casting in his drama. For though Brando worked sparingly, he was an actor or a player in his own life, a chronic instigator of intrigues, and a character who lived to find a way of being hostile or difficult with others.

He was educated at Libertyville high school in Illinois and then sent to Shattuck Military Academy. There he was expelled for indiscipline – that had been his plan. He went to the Dramatic Workshop of the New School for Social Research in New York in 1943, and studied with Stella Adler, yet he never filled the role of a determined, dedicated actor. On the contrary, he boasted of the chanciness of his career, his laziness, and a deep indifference to acting as art or vocation. But he got parts in I Remember Mama (1944), and Truckline Cafe and Candida in 1946.

He was amazingly beautiful – there is no other way of saying it, or denying its vital thrust in what happened. He had huge eyes, a wide, deep brow, an angel’s mouth, with the upper lip crested. And he could speak softly, like breathing, so the mouth scarcely moved. But he was as male as a wild animal; hunky, husky, sensual, and incoherent or rhapsodic, depending on which style worked best with the young woman of the moment.

Irene Selznick, the producer of A Streetcar Named Desire, had thought of John Garfield or even Burt Lancaster for Stanley. But she had seen Brando in Ben Hecht’s A Flag Is Born in 1946 and had been “galvanized by his power … however risky, he was bound to be interesting”. Elia Kazan, the director, wanted Brando because he knew the actor’s radiance would keep Stanley from being just a villain, the trampler upon Blanche Du Bois’s fragile bloom.

It was left to the playwright, Tennessee Williams, to decide. Brando went to see Williams who was living on Cape Cod. When he got there, both the electricity and the plumbing were out. The actor repaired them both, and then did a reading, with Tennessee taking the other parts. It was 10 minutes before they called Kazan and Selznick and told them yes. Williams wrote to his agent, Audrey Wood: “It had not occurred to me before what excellent value would come through casting a very young actor in the part. It humanises the character of Stanley in that it becomes the brutality or callousness of youth rather than a vicious older man. I don’t want to focus guilt or blame particularly on any one character but to have it a tragedy of misunderstanding and insensitivity to others. A new value came out of Brando’s reading which was by far the best reading I have ever heard. He seemed to have already created a dimensional character, of the sort that the war has produced among young veterans.”

There was a sub-text, too, for why Streetcar worked so well. Williams was gay. There was a latent sense in which Blanche was a male surrogate, the spirit of refinement and gentility, confronted by a far more brutal and modern male force. But Kazan was a devout heterosexual, and a director of the new breed that needed to find himself in the work. So he identified with Brando’s Stanley and a crude upstart vitality reducing the pretentious lady to his own level. The play surpassed its text in production, and in some profound way 1947 was ready for every fantasy that was appealed to.

Because of the special details of casting and production, Streetcar was revealed as one of those especially American works, in which energy encounters refinement, and in which the role of gender was suddenly complicated. It was an early glimpsing of a bisexuality that many people were as thrilled by as they were alarmed. But no one quite knew what was happening that first night – December 3 1947 – except that they had been poleaxed.

The audience stood. The curtain calls lasted half an hour. Jessica Tandy played Blanche Du Bois, and she was universally admired. But Brando changed the culture.

As Kazan saw it, Brando had changed the play – audiences liked Stanley more or as much as Blanche (it was only later that Streetcar became a play about Blanche). A kind of rutting force was let loose, a feeling of native American force. Brando was seen on stage half-naked (he had a flawless torso then), discarding a sweaty T-shirt, alive, urgent, unruly and golden. People of both sexes fell for him at the same moment as a classical male persona had been explored or layered, and only Brando could have held the human beast and the brooding angel in balance. It began to be possible for the American hero to be beautiful, and not just handsome.

That insurrectionary actor never again worked on stage once the heady run of Streetcar was over. There would be no Hamlet, no Coriolanus, no Antony (on stage). This was an actor who never did Chekhov or O’Neill – over the years, imagine him in three of the roles from Long Day’s Journey Into Night, or why not four? He never did Pinter, Hare, Shepard or Mamet. Never again elected to be there pretending, just a matter of a few feet away, in the same electric space and air as the audience.

Why? He was not a heartfelt actor, he said, and he was certainly not charitable. There was a mean streak in Brando, a cunning country boy’s lust for money and fame and adulation – all the poisons he would turn from in horror once he had tasted them. So he went to Hollywood and became a movie actor – it was what Stanley would have done; it was also the quicker way for someone who wanted to despise himself. In 1950 came The Men.

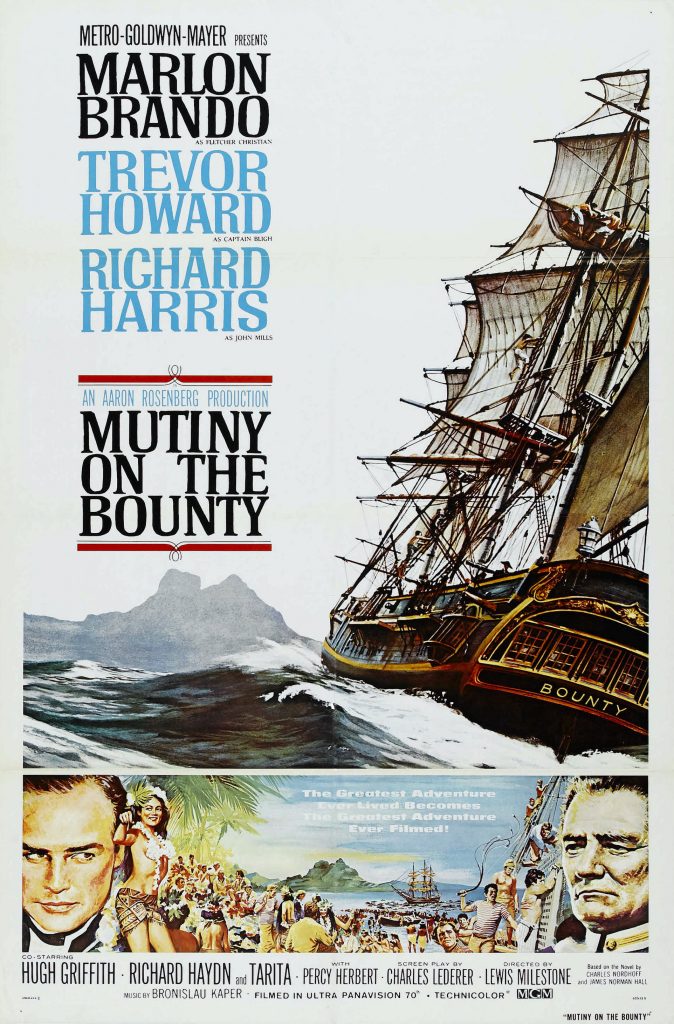

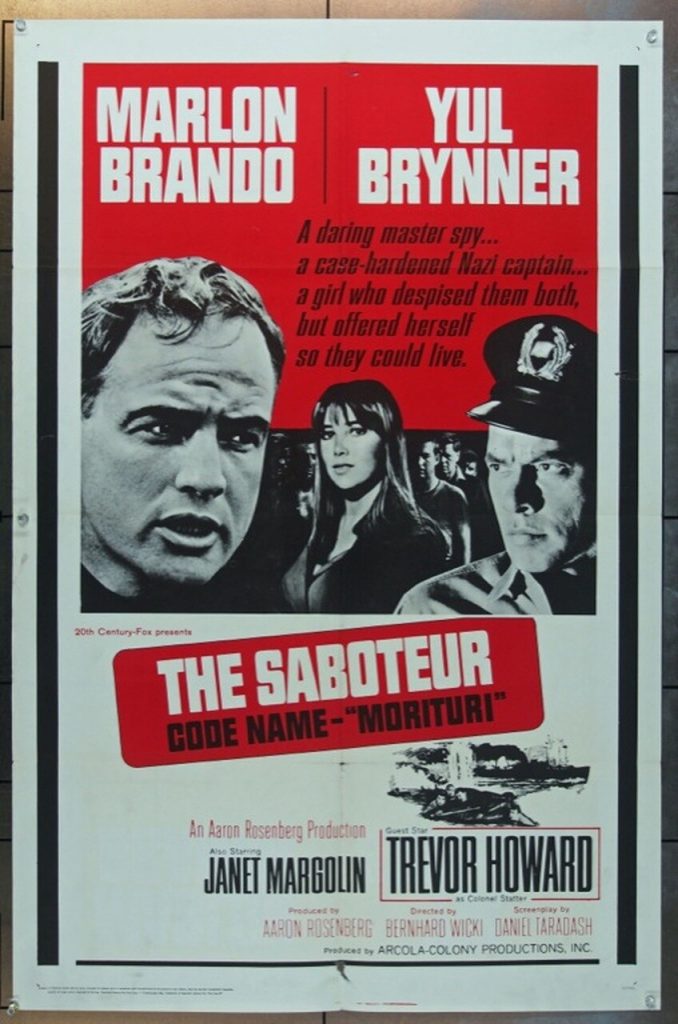

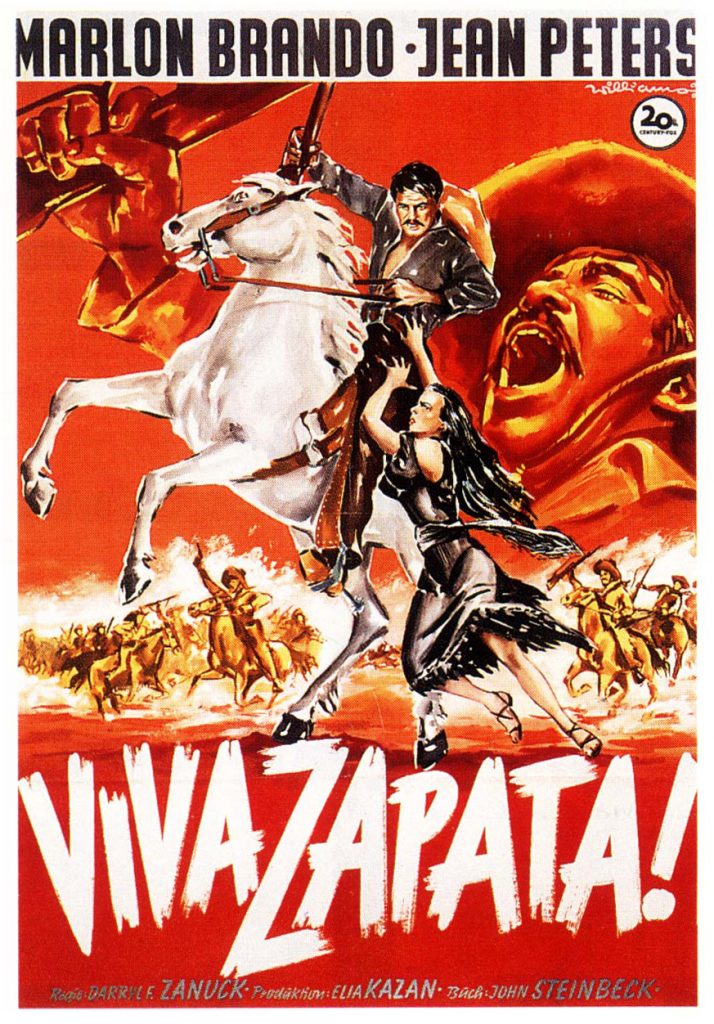

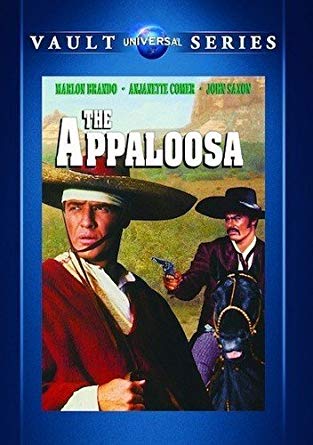

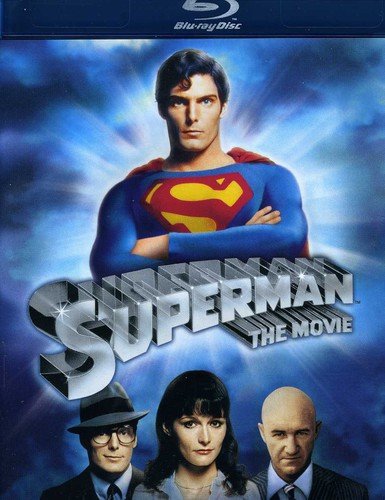

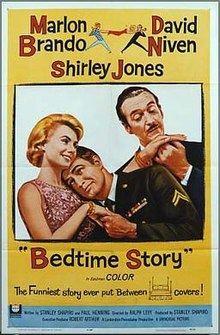

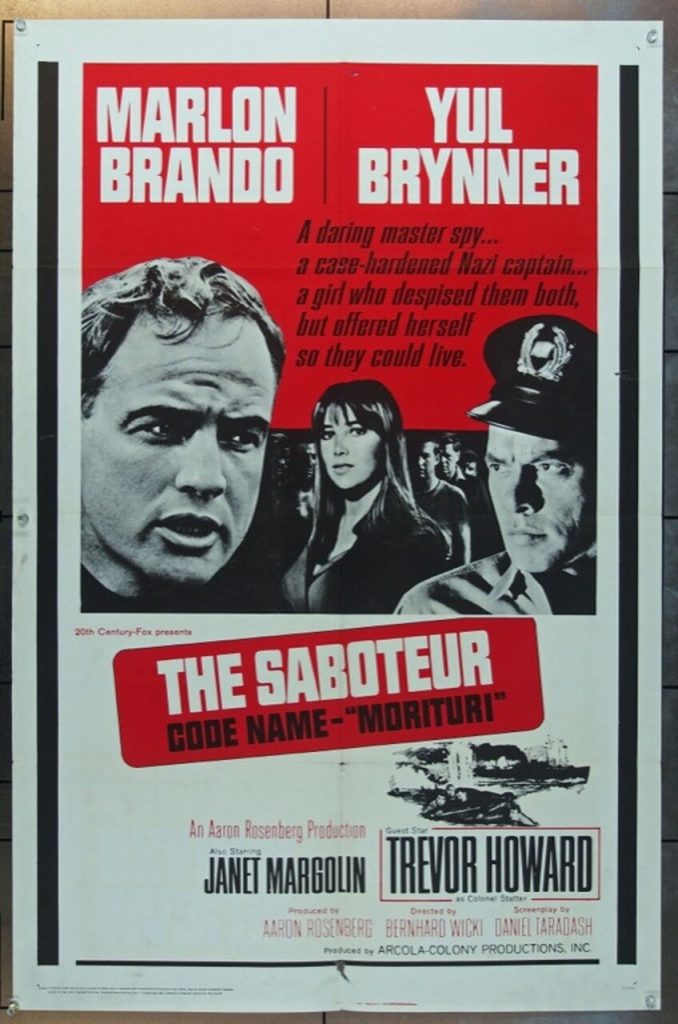

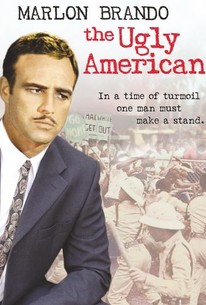

Of course, that was far from ruin. But one might as well say, without apology or explanation, that most of the film work he did was shameful junk, ill-chosen, slapdash and devoid of soul. Get ready, it is a long list and included: Désiree (1954); The Teahouse Of The August Moon (1956) Sayonara (1957); The Young Lions (1958); Mutiny On The Bounty (1962); The Ugly American (1963); Bedtime Story (1964); The Saboteur Codenamed Morituri (1965) Appaloosa (1966); A Countess From Hong Kong (1967); Candy (1968); The Night Of The Following Day (1969); The Nightcomers (1971); Superman (1978); The Formula (1981); Christopher Columbus (1992). That is a lot of rubbish to clean out in the search for gold – and it must be pointed out that Brando, quite early on, had unusual power in determining his own projects.

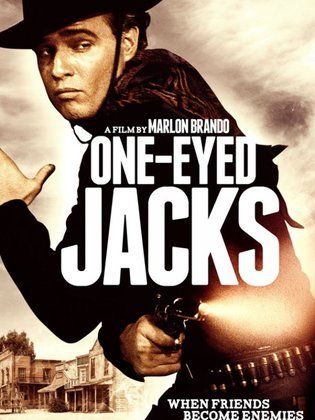

He is the great actor, and the idol of a generation of actors who have been directors, producers and the arbiters of their own careers. Brando directed once – on One-Eyed Jacks (1959) – before boredom and sourness took over, but seldom had the patience, the stamina or the courage to be master of his own fate. Instead, he liked to be seen as the victim of a malign, stupid system, for that came to the aid of his tricky mixture of indolence, disbelief and hypocrisy. Still, a lesser actor – Paul Newman, say, only a few months younger – built up a far more consistent body of work than Brando dared.

That said, there are films, or passages from films, that explain the way so many people felt – not least Newman, Jack Nicholson, Warren Beatty, Dustin Hoffman, Al Pacino, Robert De Niro … and so on, to the bottom of the page. Nearly every American actor since has moved through his own work mindful of Brando’s record and potential.

He was doing pictures early, in an age when William Holden, Kirk Douglas, Burt Lancaster and John Wayne were the rage. Their style was clearcut, confident and unambiguous. So it meant all the more that Brando’s acting was made, palpably, out of indecision – in pauses, aborted gestures, frustrated eloquence, and a feeling of the enormous, untidy accumulation of experience that could not just deliver on “Action!” He was laughed at for this: comedians did Brando impersonations. But the new attitude – Method or beyond Method – was the future. Every young actor, from James Dean on, and every rock singer, from Elvis down the line, was affected by Brando’s pent-up inwardness.

He was a paraplegic in Fred Zinnemann’s The Men – the first role that defined his affinity with frustration. He reprised Stanley in Kazan’s film of Streetcar (1951) – with Vivien Leigh instead of Tandy, in a censored version, but still our nearest to a record of 1947. He was the hero in Viva Zapata! (1952), and a fine, if unprofound, Antony in Joseph Mankiewicz’s Julius Caesar (1953).

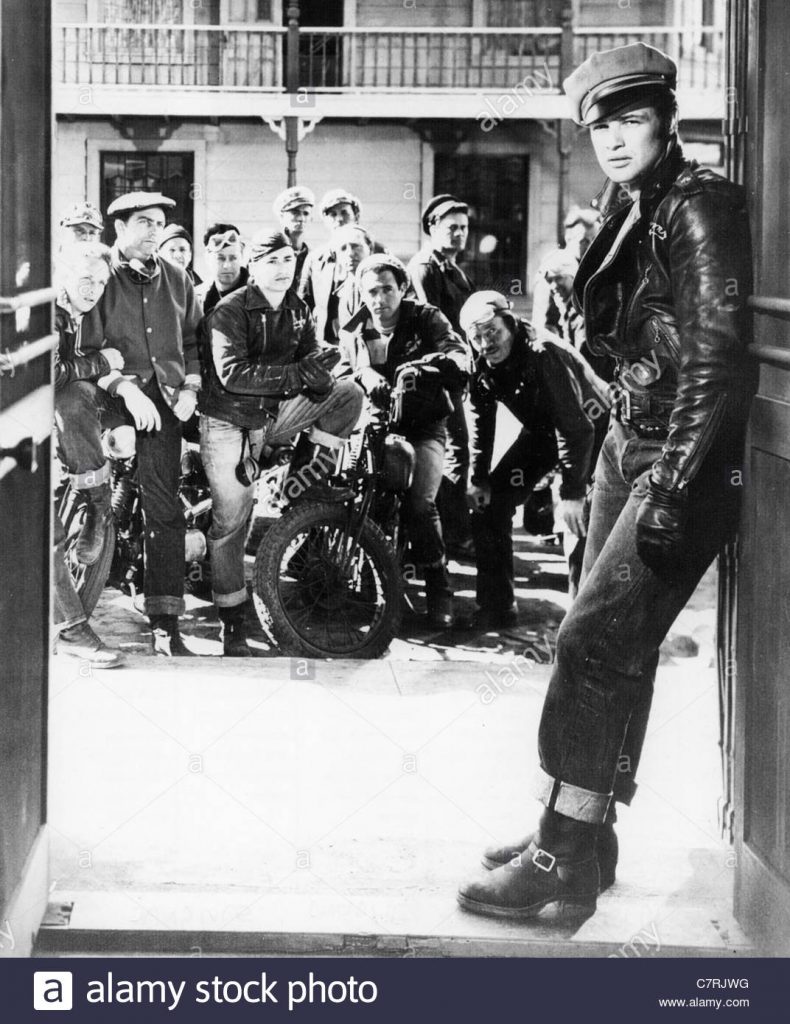

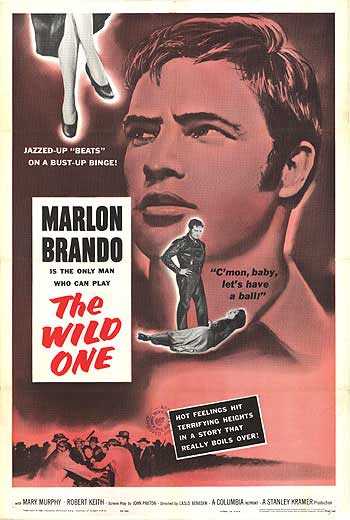

John Gielgud (Cassius) beheld him, and then invited Brando to come to England for a season of plays they would do together – Brando declined, and lived on to see the noble creative vitality of Gielgud, working, working. Brando was Johnny the biker in The Wild One (1953), a very camp figure, a gay icon, but a sulky kid who, when asked “What are you rebelling against?”, knew young America’s cool answer, “What have you got?”

Then, in 1954 he was the ex-boxer, the one who could have been a contender, in On The Waterfront, that curious apologia for informing made by Kazan and Budd Schulberg after they had testified to the House Un-American Activities Committee. Brando got an Oscar for that film after being nominated four years in a row – for Streetcar, Zapata, Julius Caesar and Waterfront. The film doesn’t wear too well. Too much of it looks like Actors’ Studio guys pretending to be dockers and lowlifes. But Brando’s deliberately battered beauty was as poignant as the self-discovery in a dumb kid that he had let himself be used too often.

That was his first period, his youth, and it is fascinating to note that it ended as James Dean arrived on the scene. They met, warily. Dean was younger, hungrier – and Brando had been offered the role that Dean played in East Of Eden; indeed, Kazan had wanted Brando and Montgomery Clift as the brothers. Brando felt older, more experienced, both tired and bored by the fame of being an idol. He diversified – that’s where the trouble started. He was amusing doing Sky Masterson in Guys And Dolls (1955), where he sang and danced like an old boxer anxious not to rip his new suit. But too many of the films were beneath him, and too many of the attempts to dress up and do an accent were patronising.

He was superb, with Anna Magnani and Joanne Woodward, in Sidney Lumet’s The Fugitive Kind (1960) – from Tennessee Williams again – a truly neglected picture. In One-Eyed Jacks, he could not see beyond the mean-spirited vengefulness of the story; he shot miles of footage and gave up on the editing. Some have made a cult of the film, but it is inert and pretentious.

And so his career became a mystery. There were inexplicably wasteful projects, and then suddenly the authentic actor was back – in The Chase (1966), Reflections In A Golden Eye (1967), or in 1969 in the very adventurous Burn! (also released as Queimada). That picture was made by Gillo Pontecorvo in Latin America, and it cast Brando as an English adventurer in the service of corrupt imperialism. It was a picture made out of political conscience and in defiance of Hollywood, and it is well worth pursuing.

By 1970 or so, the man was a mess and a figure sinking beyond the cultural horizon. He lived a good deal in Tahiti. He had acquired three marriages – to Anna Kashfi (Anglo-Indian), Movita Castenada (Mexican) and Tarita (Tahitian). There were many more affairs, and he was the father of at least 11 children. He liked to seduce married women, then abandon them. He would humiliate husbands and sometimes he exulted in a kind of mutual sexual degradation. Equally, there were women who said he was a magical lover and an enormous influence on their lives. There was also the feeling that as an actor he had become so unpredictable and wayward as to be out of control.

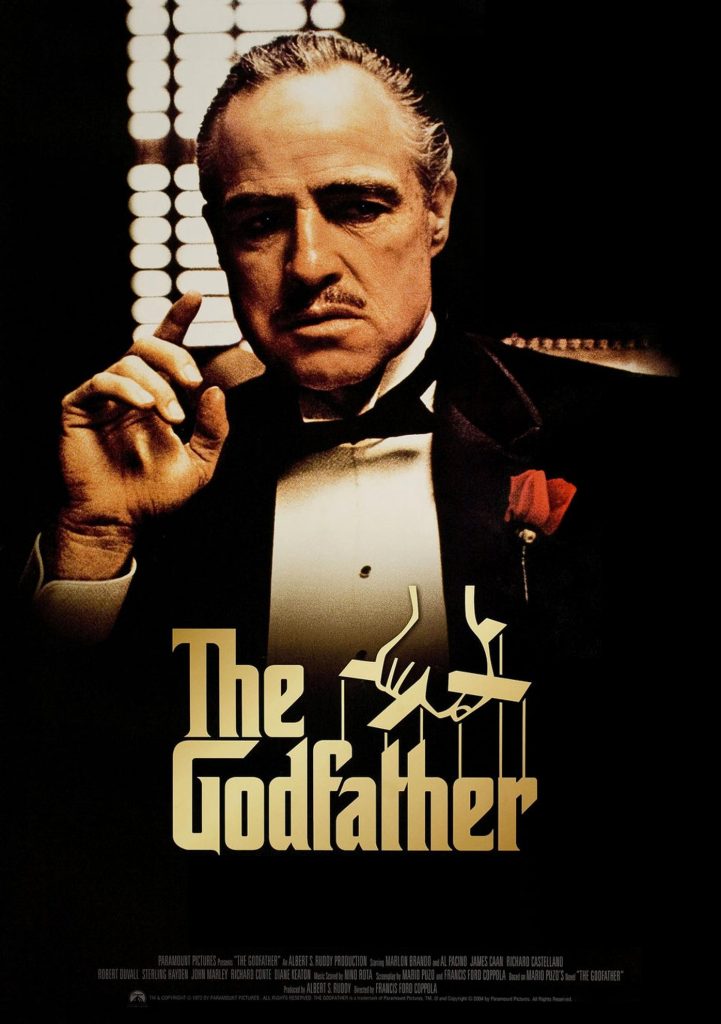

Then in two years, close to the age of 50, he grabbed at work so extraordinary that he secured his reputation – and made his subsequent vanishing all the more tragic. He did two films, one entirely conventional, the other so radical it risked being banned. In The Godfather (1972), he was Vito Corleone, that old standby – a master criminal and the rock on which family is built. It was not a difficult part for him, once he had got the look, the voice, and the cotton wool in his mouth. But the film was a smash hit (his first such success) and Vito was a model of the new American ambiguity: a killer, a pioneer of criminal method, and a man with a sense of love, duty and respect. His boys and followers – James Caan, Al Pacino, Robert Duvall, John Cazale – attended to him like disciples with their master. He won a second Oscar and sent an alleged Apache maiden to refuse it, with a long speech about American abuse of native Americans. The maiden wore buckskins and false eyelashes; it turned out she was some kind of actress.

And then he agreed to do Last Tango In Paris (1972) for Bernardo Bertolucci – the last dissolute, shabby, vile act of the former angel, a role that mined his own past (because he let it), that depended on his own great fascination with sex and its power, as well as his tormented feelings towards women. And he did it casually, without the vibrato of “this is hugely dangerous and difficult”. If anyone doubts Brando’s greatness, see this film and absorb the sheer absent-mindedness of the performance – he is so deeply into his role that he exposes only a fraction of the man’s life. He seems not on show, yet we see more of human nature than film has ever prepared us for. In Last Tango, the “has-been” suddenly appeared 10 miles ahead, not even bothering to smile at all the rare, new places he had been. The film is lacerating, but Brando’s pain in character is subdued by the achievement of the acting. Yet the whole thing was sly and subversive, for it whispered, see, see what you have been missing.

The missing became greater still after Last Tango. He worked far less often. He began to put on fearsome weight. He let it be known that the world and its audiences hardly deserved him. But he made grotesque monetary demands for the nonsense of Superman.

And in a film like The Missouri Breaks (1975) – with Jack Nicholson, the latest next Brando – he kept changing his character, as if to ridicule such things. The result was hilarious – we have always seen too little of Brando the comic – but neither Nicholson nor director Arthur Penn could keep up with his whims.

Equally, on Francis Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1977), Brando added to the hideous burdens of that production by imposing himself as a terribly overweight and under-prepared actor, determined to philosophise about the part and the picture, ready to embark on profuse improvisations and diversions. The result was not pretty or effective – and it was less than generous to the director who had made The Godfather with him.

He made four films then in 15 years, with only the gentle, amusing The Freshman (1990) and Don Juan De Marco (1994) in the plus column. In the latter, he was a sleepy, dreamy psychotherapist fascinated by Johnny Depp’s claim to be Don Juan, and brought back into merry contact with his wife, played by Faye Dunaway. Though a love scene between them was played in near dark, there was little attempt to mask Brando’s bulk, and every sign of his abiding skill.

But his family life was chaotic and destined for the courts and the tabloids. He gave occasional interviews in which he sneered at the process and seemed to glory in his own monstrousness. When he came to write his autobiography, he remarked publicly on the idiocy of publishers paying so much money – and he even had a plan once to have several women from his life do a chapter each, over which he would preside as silent, taunting pasha.

The autobiography is neither helpful nor appealing, though its account of his early years is fresh and intriguing. Peter Manso published a very lengthy biography, Brando (1994), that gave all too rich a portrait of the ugly manipulation of much of his life. Will there ever be a book that “explains” the man? I doubt it. He was a tragedy of his own wilful, self-abusive resolve. He was a complex masquerader in life’s unwinding and that form challenged him so much more than the texts for plays or films. There might one day be a great novel founded on a figure like Brando. But there is reason to suspect he preferred to leave mystery, wreckage and a confounded public. In all of which he succeeded.

Acting does date. It is already a cause for perplexity that John Barrymore was once passionately regarded as the greatest of American actors. Brando’s Method persona was parodied from the outset, and his true Stanley is now “remembered” by very few people. But we will have The Men, Zapata, On The Waterfront, The Fugitive Kind, The Chase, The Godfather, Last Tango … it is enough, I suspect, for him to become as representative of cinema as Garbo, Chaplin and Mickey Mouse. And as the travail and melodrama of the awkward life passes, so we can look at the movies and recall that we were young, once, when Marlon Brando was doing such things. It was often veiled, supercilious and sinister, but on screen he made us an offer we couldn’t refuse.

· Marlon Brando, actor, born April 3 1924; died July 1 2004

His obituary by David Thompson in “The Guardian” can be accessed here.