Joan Fontaine obituary in “The Guardian”.

Her “Guardian” obituary by Veronica Howell:

It was hard to cast the lead in Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, filmed by Alfred Hitchcock in 1939. The female fans of the bestseller were very protective of the naive woman whom the widower Max de Winter marries and transports to his ancestral home of Manderley. None of the contenders – including Vivien Leigh, Anne Baxter and Loretta Young – felt right for the second Mrs de Winter, who was every lending-library reader’s dream self.

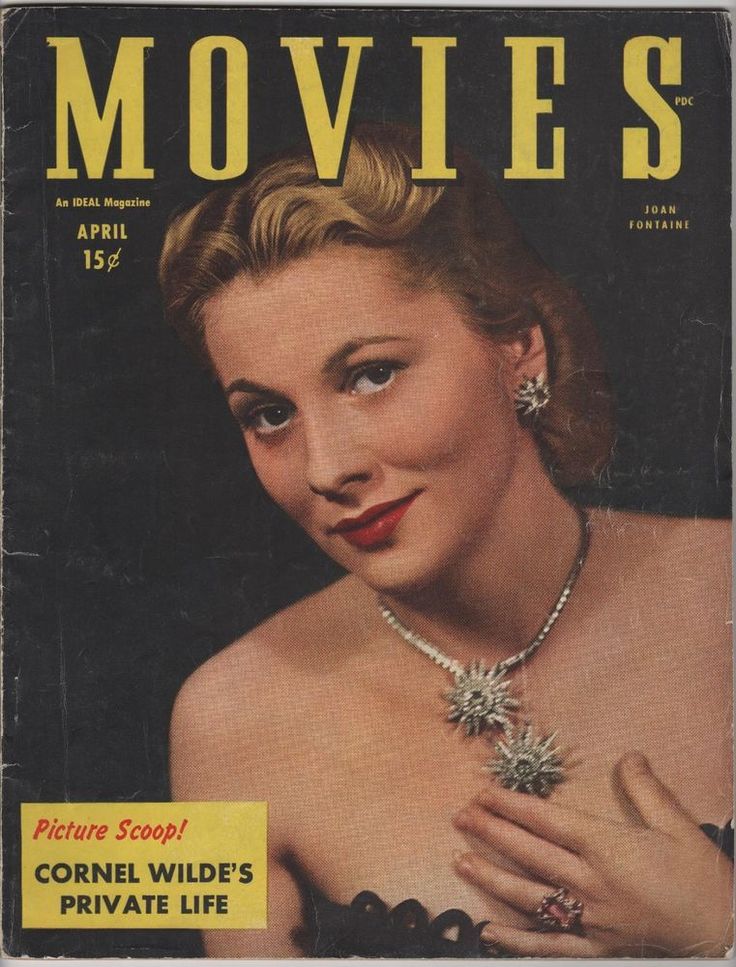

To play opposite Laurence Olivier in the film, the producer David O Selznick suggested instead a 21-year-old actor with whom he was smitten: Joan Fontaine. The prolonged casting process made Fontaine anxious. Vulnerability was central to the part, and you can see that vulnerability, that inability to trust her own judgment, in every frame of the film. The performance brought Fontaine, who has died aged 96, the first of three Oscar nominations.

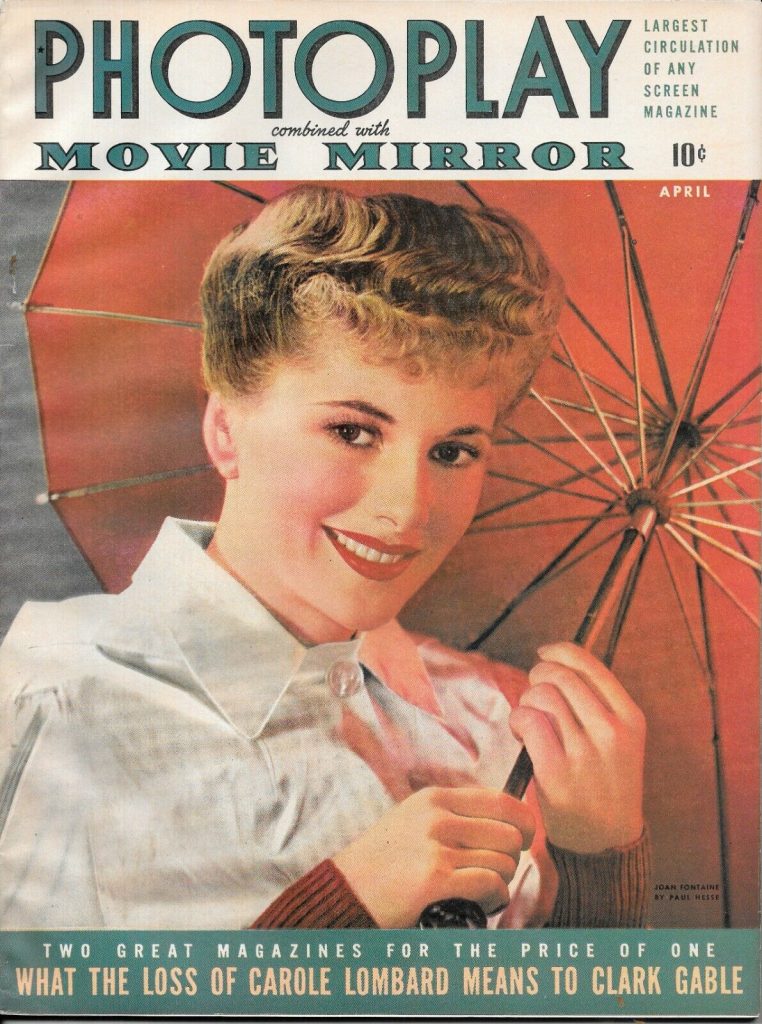

She was born Joan de Beauvoir de Havilland to British parents – Walter, a lawyer, and Lillian, an actor – in Tokyo, where her father was working. Her parents divorced when she was two and, along with her older sister, Olivia de Havilland, she grew up in California.

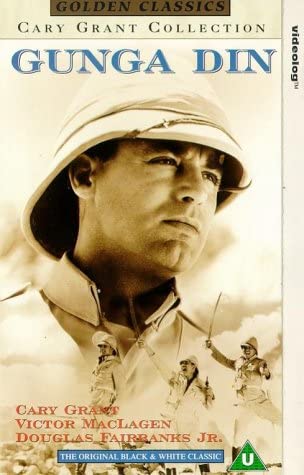

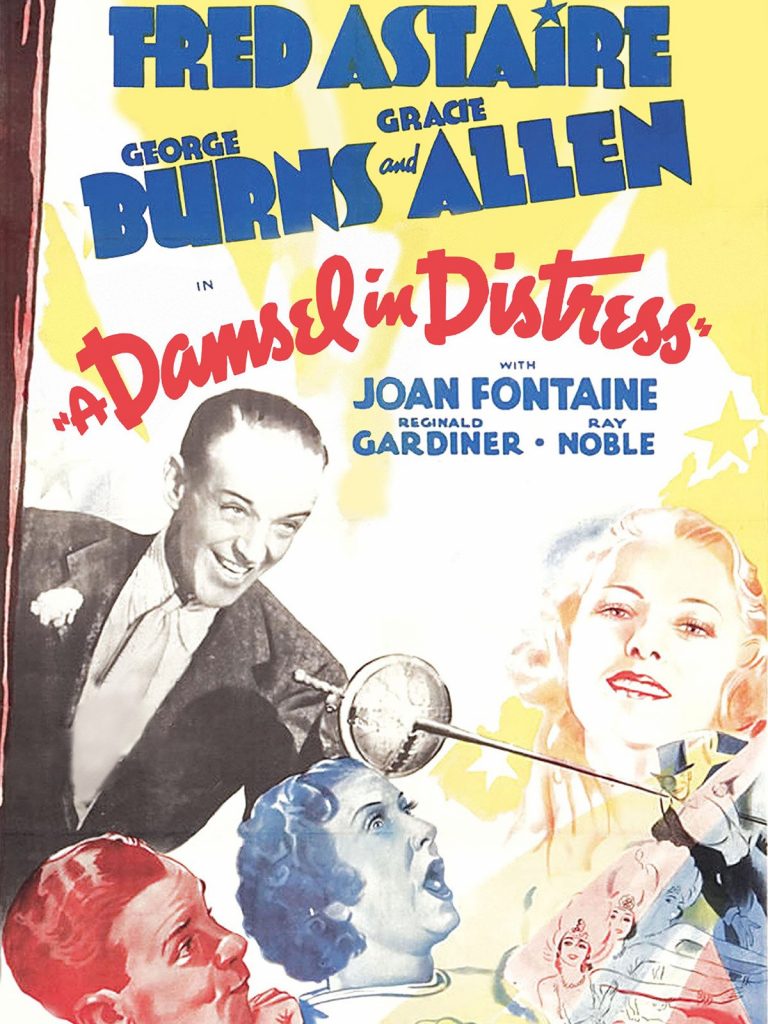

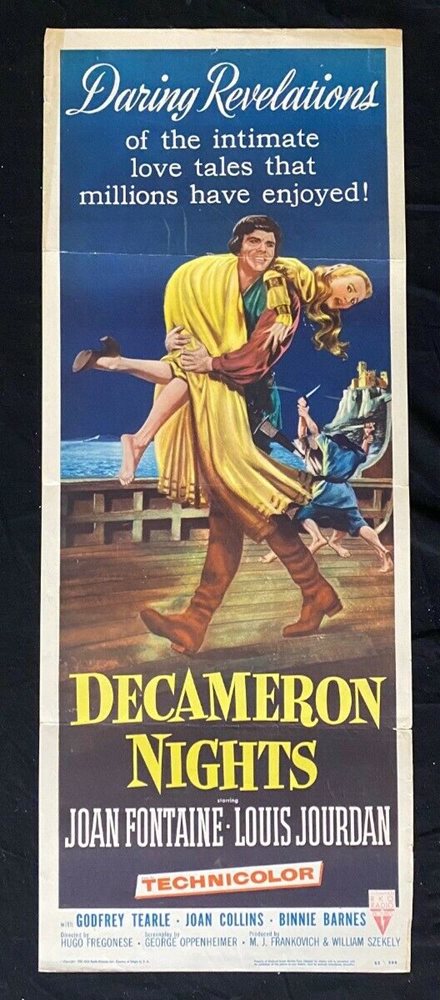

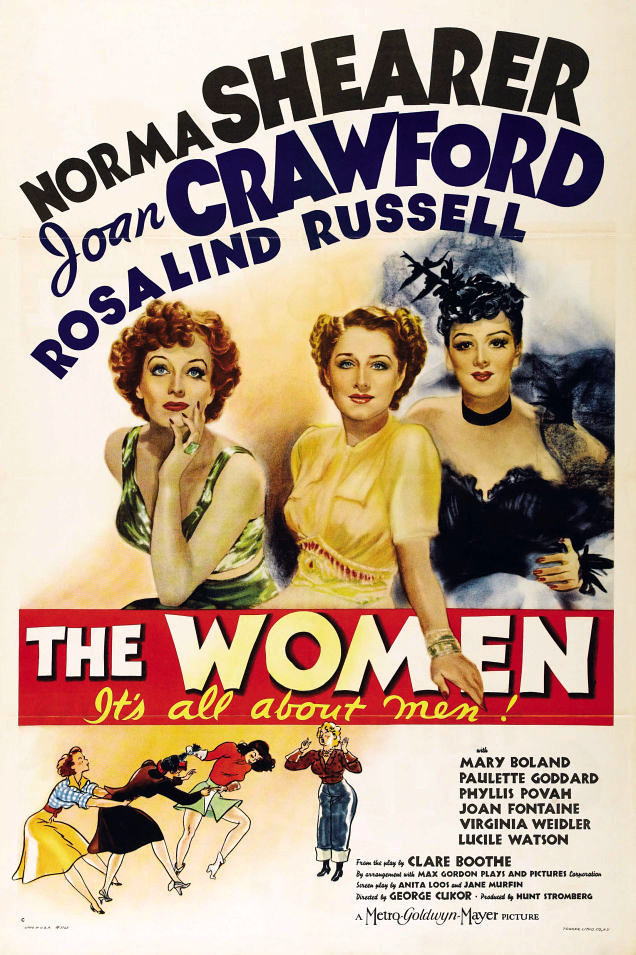

Olivia’s beauty won her lead roles on the arm of Errol Flynn, while Fontaine – who took her professional name from her mother’s remarriage, to George Fontaine – lagged behind. No less fine-boned but more tentative, Fontaine seemed somehow more British than her sister. She tried out on the West Coast stage and took small movie parts, advancing gradually in 1939 to be the dewy thing sighed over byDouglas Fairbanks Jr in Gunga Din and the dopiest of The Women in George Cukor’s film of Clare Boothe Luce’s Broadway play.

Meanwhile, De Havilland had been nominated for an Oscar for her performance in that year’s Gone With the Wind. Selznick seems to have intuited that Fontaine’s envy and distress about her more glamorous sibling would inform her playing of the chatelaine of Manderley.

The period from the late 1930s to the end of the second world war is usually seen as an era of ever stronger movie women: career gals, swell dames and tough cookies. But there was a genre of threatened-women films, too: not the physical threat of modern stalker/slasher films, but something subtler, where a woman is destroyed by her fears and insecurities about men and her social competence.

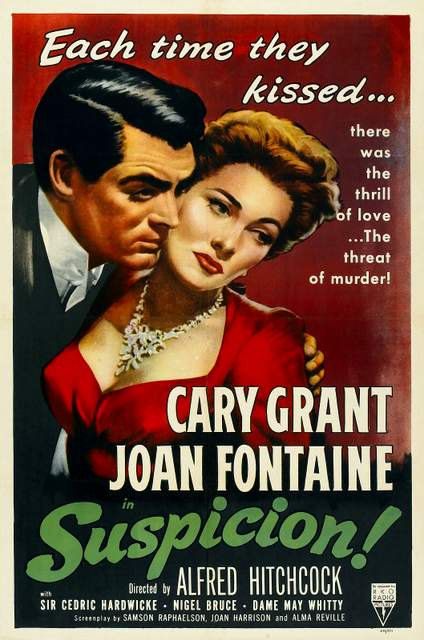

In Rebecca and in Suspicion (1941), Fontaine’s next film for Hitchcock, the heroines – although that’s rather too active a noun for them – marry men more exciting and worldly than they believe they are entitled to. In Rebecca, Fontaine is tempted to take her own life because she is made to feel unworthy of her husband (although he proves to be a lying murderer); in Suspicion she comes near to a breakdown because she believes that her husband (Cary Grant) is trying to murder her.

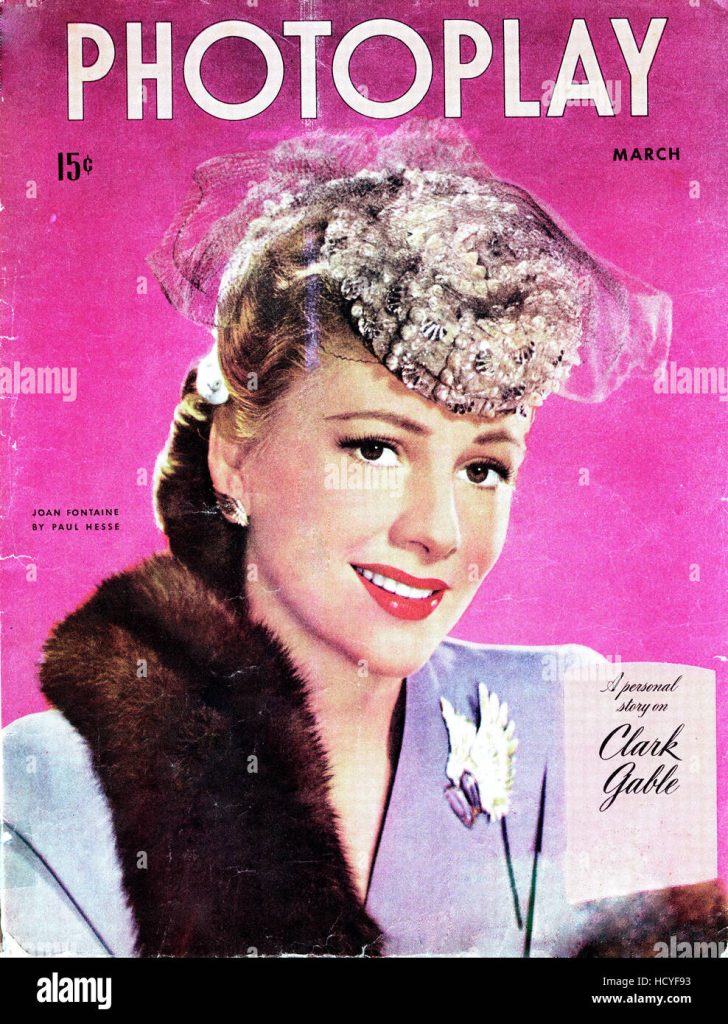

Fontaine had deserved an Oscar for Rebecca (she lost to Ginger Rogers for Kitty Foyle), but she won for Suspicion, beating De Havilland (nominated for Hold Back the Dawn). Rebecca had updated Charlotte Brontë, so it seemed fitting that Fontaine was cast as Jane Eyre, opposite Orson Welles as Mr Rochester, in a 1943 film directed by Robert Stevenson. She has the wary stubbornness all right, but not the soul afire under the alpaca frock.

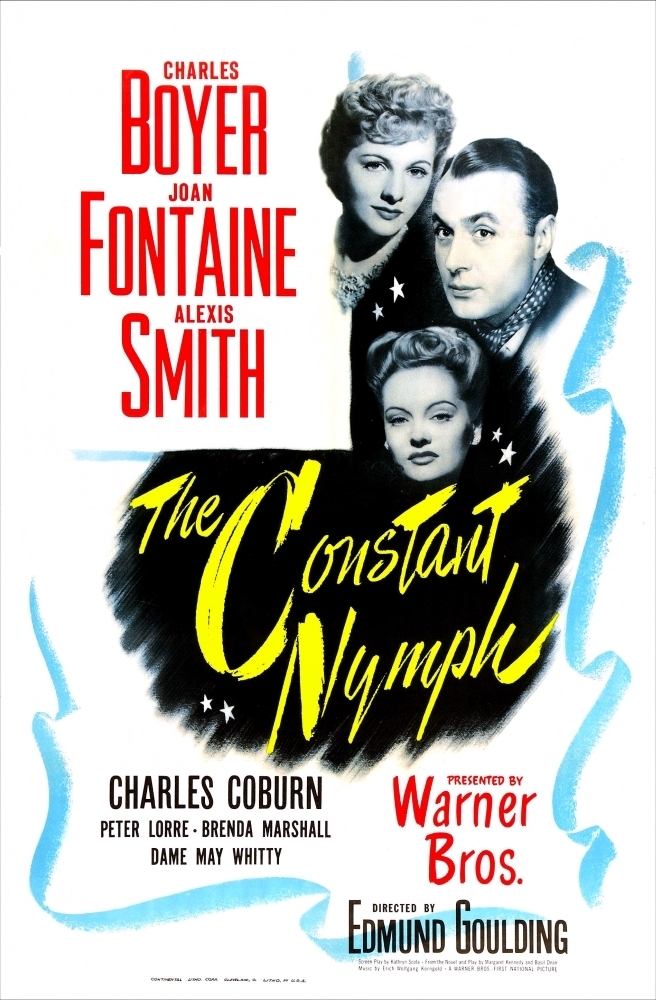

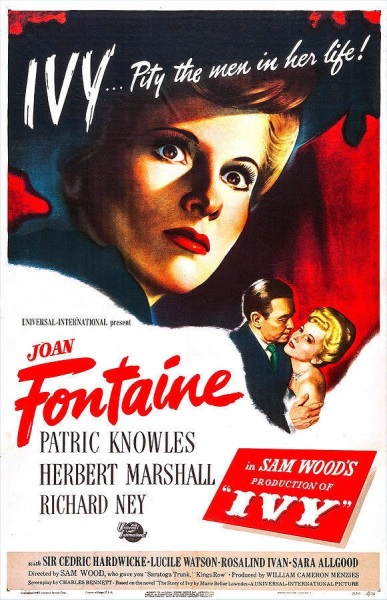

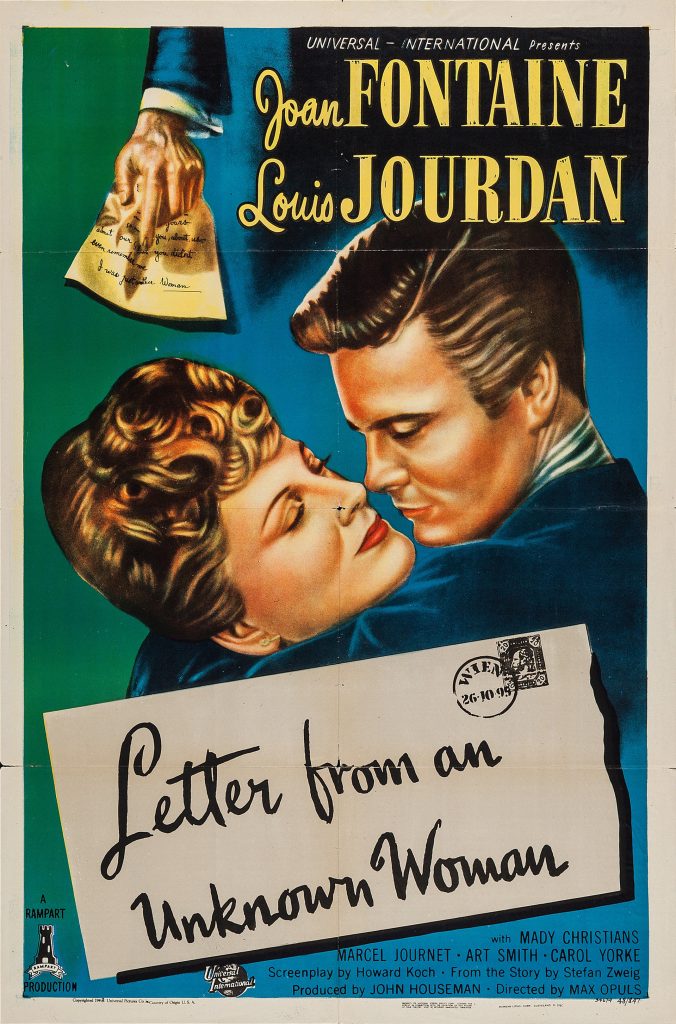

There was another Oscar nomination (for The Constant Nymph, 1943) and another Du Maurier adaptation, Frenchman’s Creek (1944). Her onscreen tension appealed to audience sympathy when she was young, and it could also be used, with skill, to suggest sinful scheming, as in Ivy (1947), in which she played a poisoner. But the best film she made was Max Ophüls’s Letter from An Unknown Woman (1948), in which her nervous romanticism was heightened into heroism. Her character had once adored a concert pianist neighbour and become one of his many conquests (and pregnant by him). She abandons her safe marriage and child for one more assignation with the weary creep – only to find he does not remember her. She is just another lovely face.

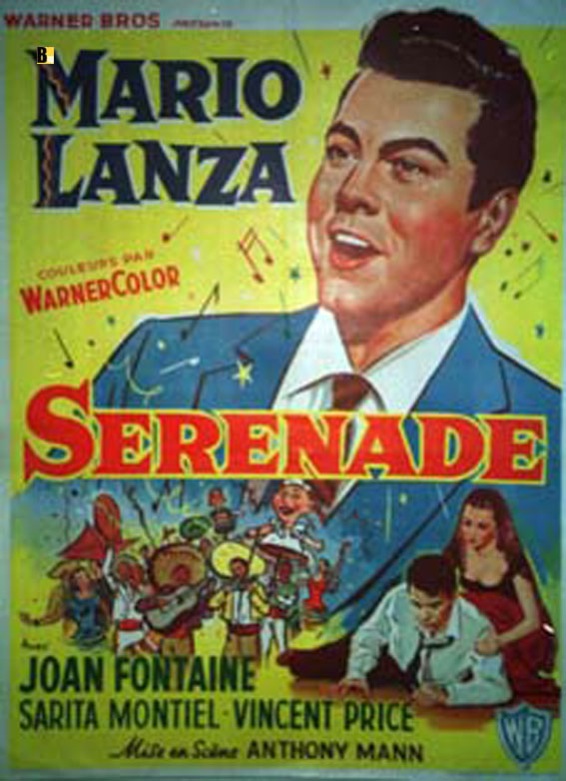

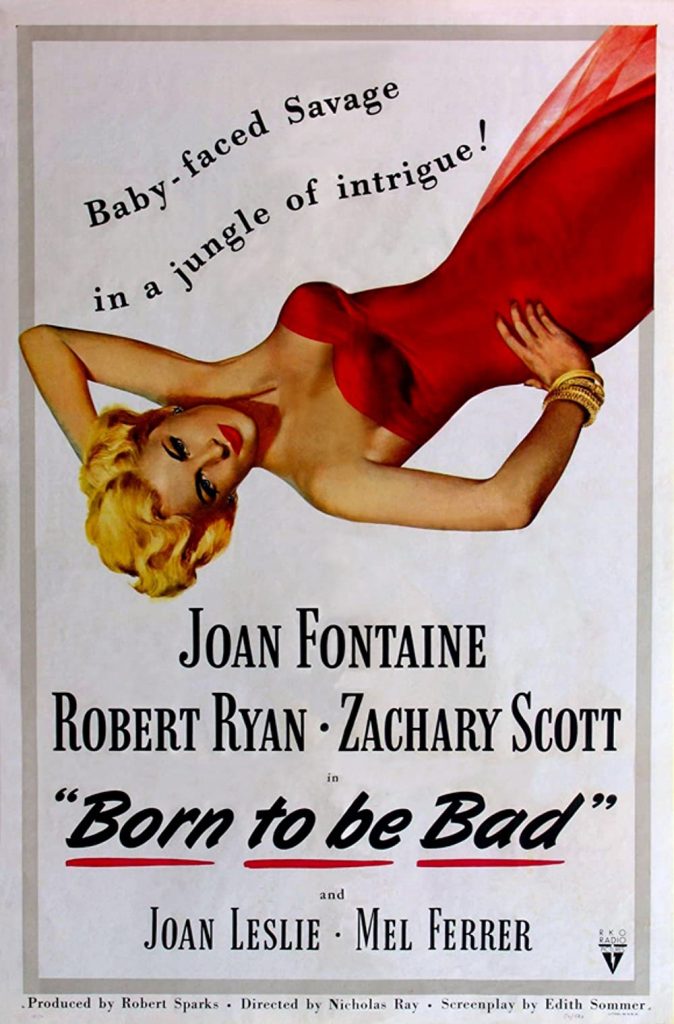

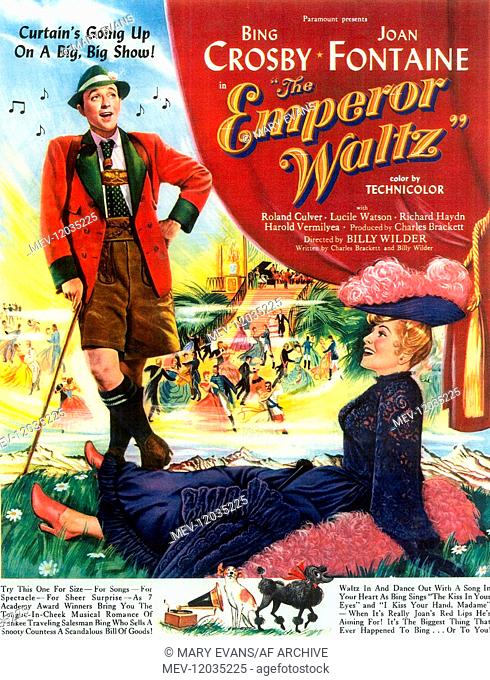

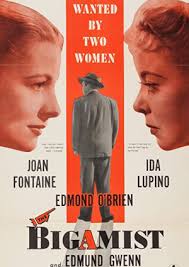

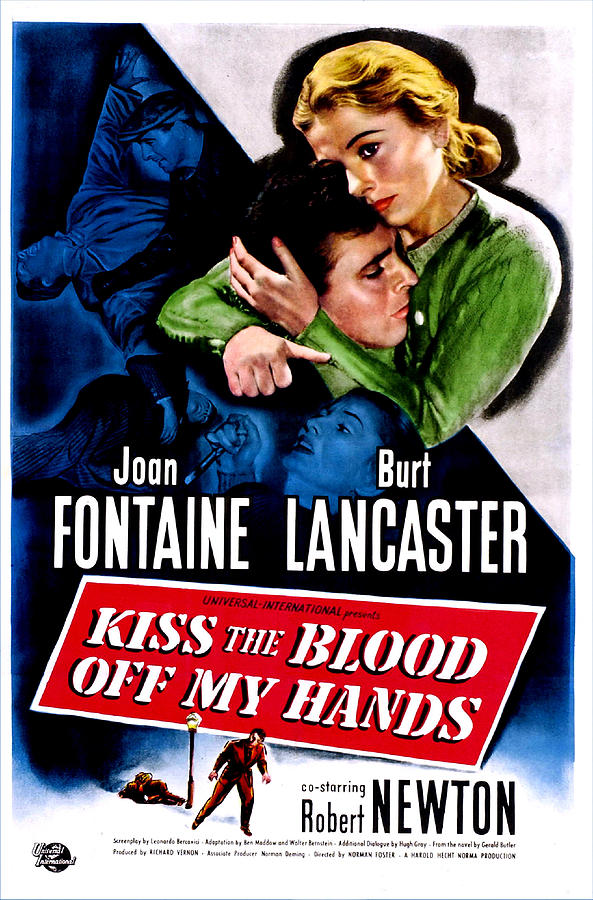

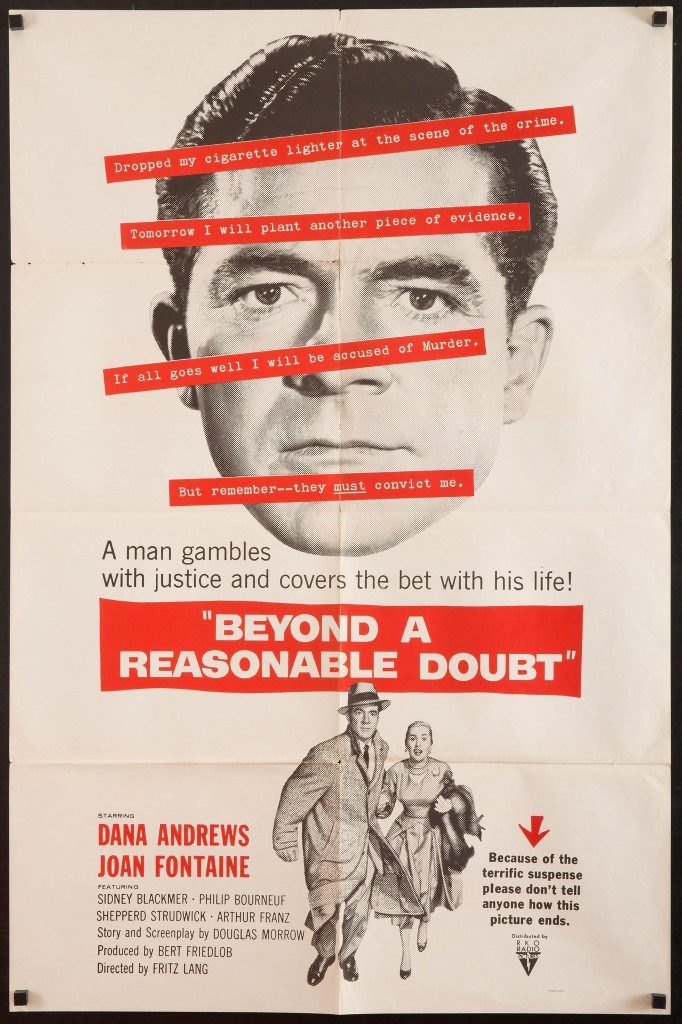

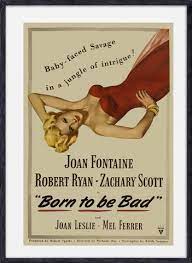

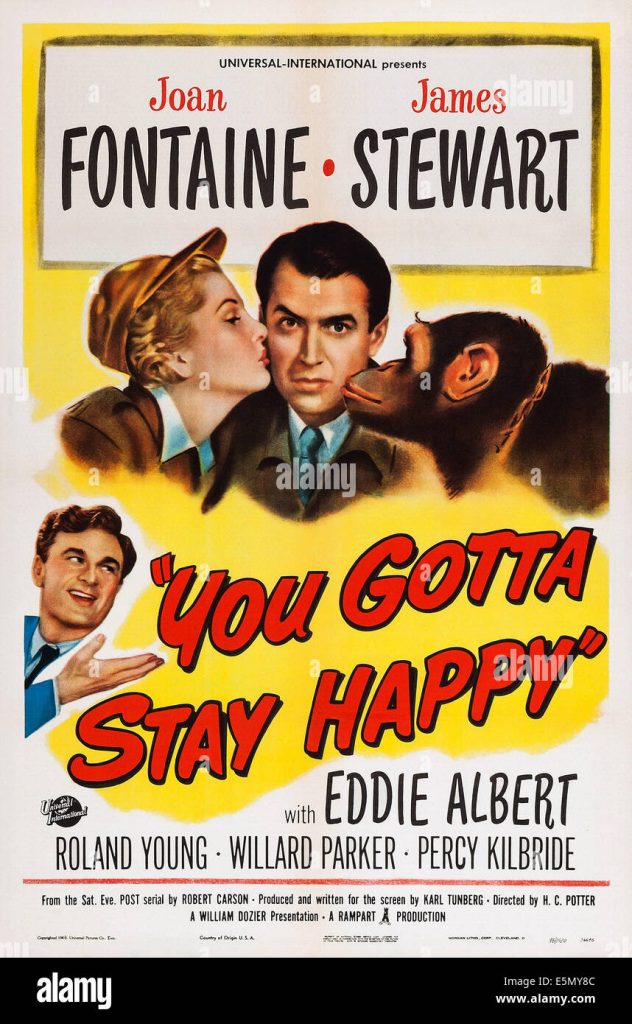

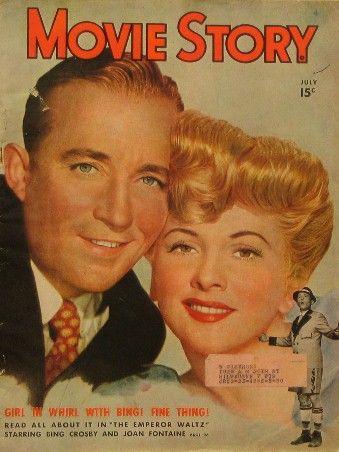

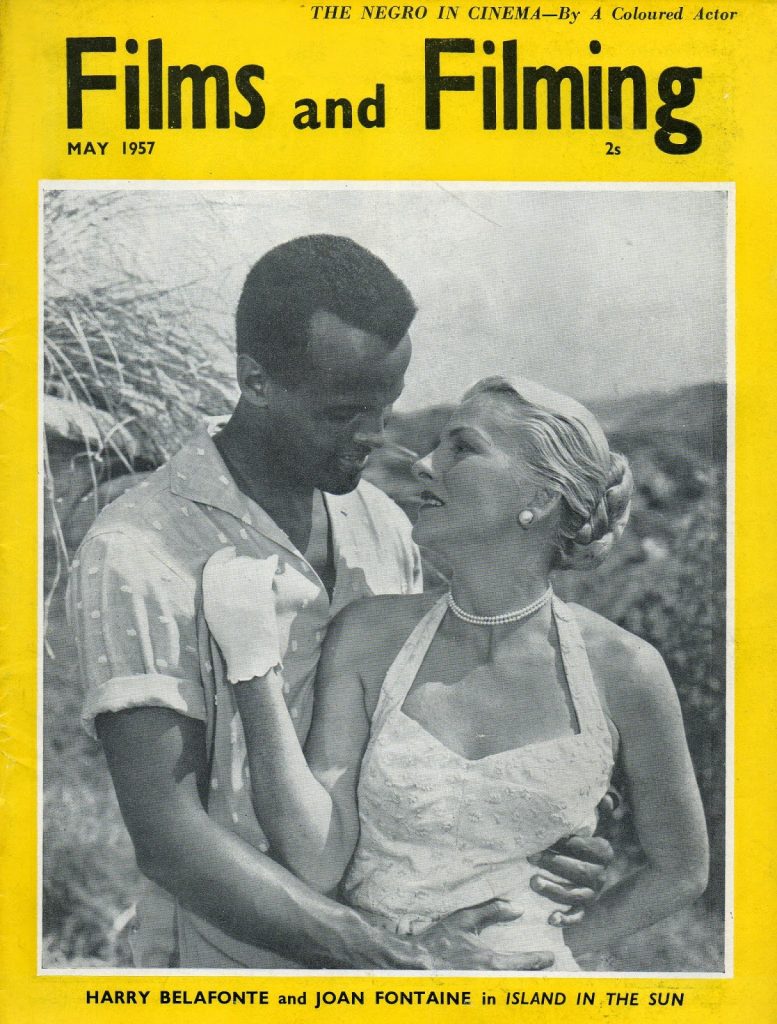

If, at this point, Fontaine had moved to, say, France she might have had 10 or 20 good years and films, clad in couture to flatter the physical sophistication she had achieved by her 30s. Instead, she was indifferent in Hollywood films by directors who should have made better – The Emperor Waltz (Billy Wilder, 1948), Born to Be Bad (Nicholas Ray, 1950), Serenade (Anthony Mann, 1956), Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (Fritz Lang, 1956) and Until They Sail (Robert Wise, 1957). There was a rather pearls-and-twinset Lady Rowena in the glum Ivanhoe (1952) – did she take the part to prove she could do what her sister had done so well in swashbucklers? – and a then shocking suggestion of an interracial affair with Harry Belafonte in Island in the Sun (1957). In her last major film she was the support – significantly, the sister – in F Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night (1962).

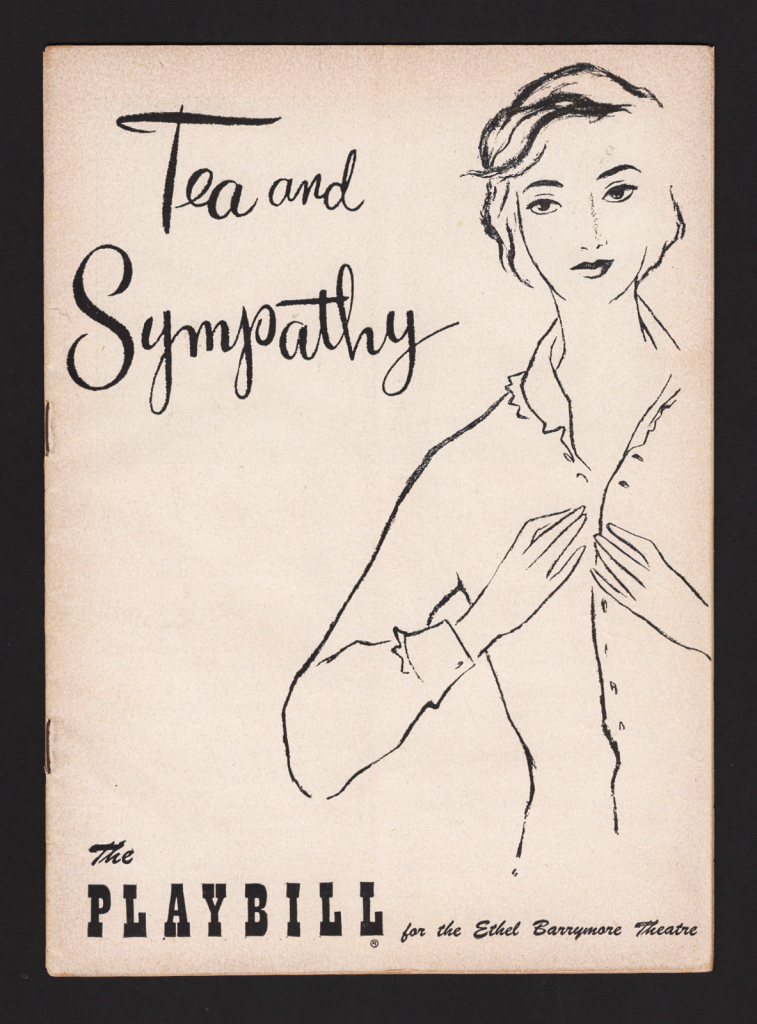

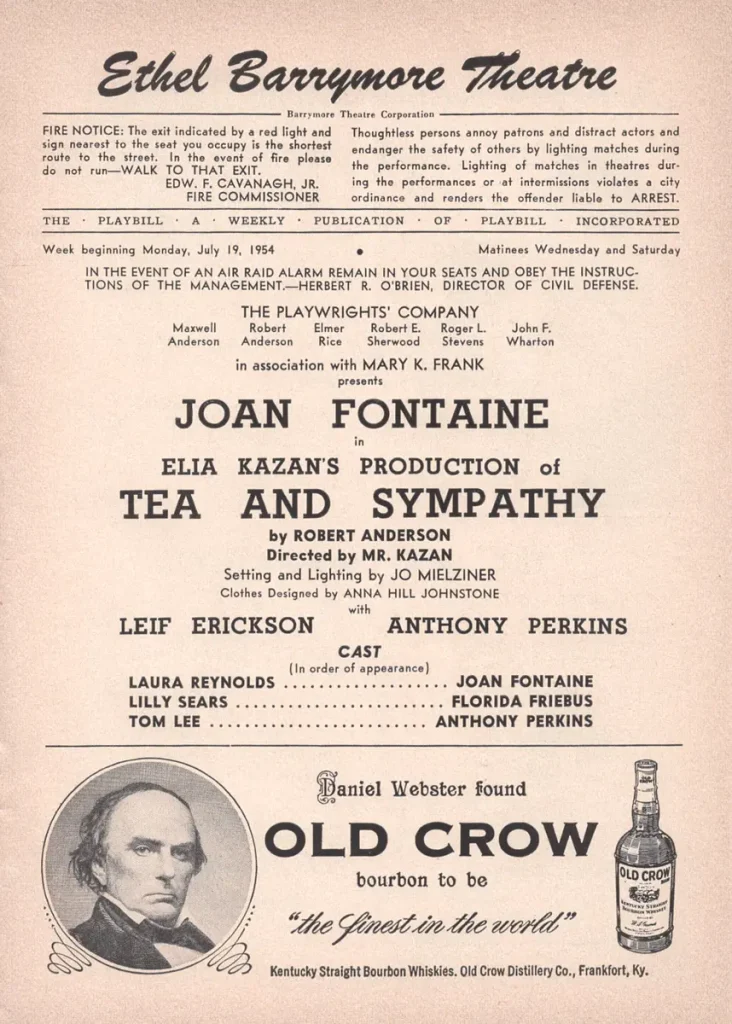

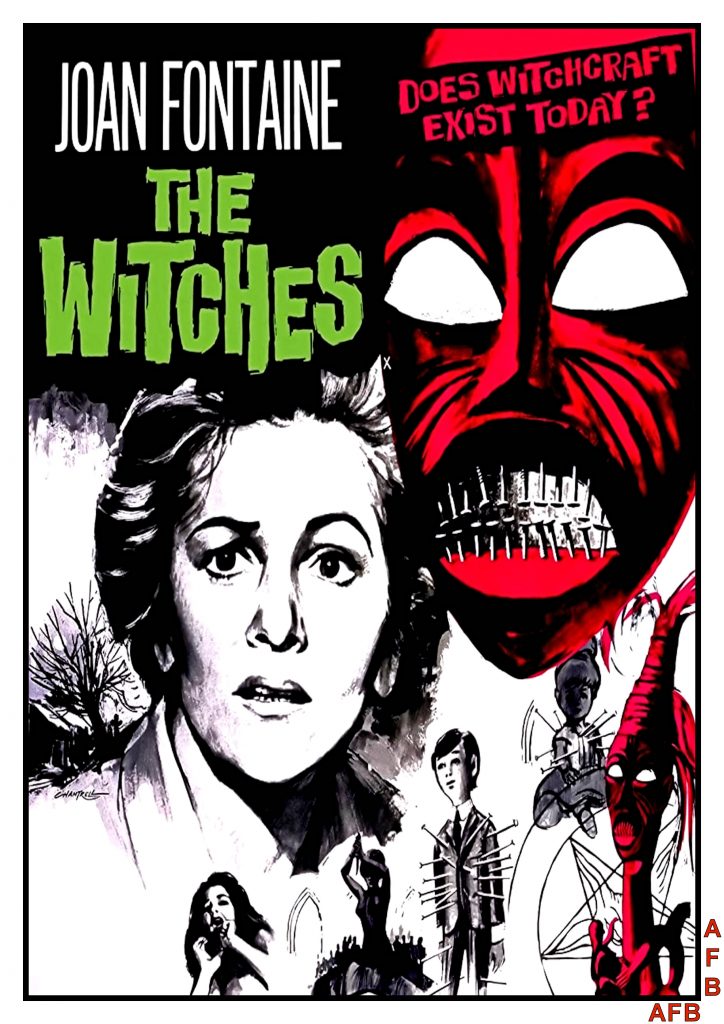

Fontaine appeared twice on Broadway as a replacement for current stars, in lieu of Deborah Kerr in Tea and Sympathy, in 1954, and succeeding Julie Harris in Forty Carats, in 1968, both parts closely linked to her introverted screen roles. She continued on stage, though never Broadway again, until she was in her 70s, and worked in television (most successfully a soap, Ryan’s Hope, in 1980) and TV movies, her last appearance being in Good King Wenceslas, on the Family Channel, in 1994.

In her autobiography, No Bed of Roses (1978), she was fearlessly honest about the fearfulness that had dominated all of Hollywood in her prime. Yet in her own life, Fontaine was a brave pilot of planes and balloons, and a deep-sea diver. She married and divorced four husbands: the actor Brian Aherne, the film producer William Dozier, the screenwriter Collier Young and the journalist Alfred Wright.

She is survived by her daughter, Deborah, from her second marriage, a grandson, and her sister.

This “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed here.