Heather Sears obituary in “The Independent” in 1994

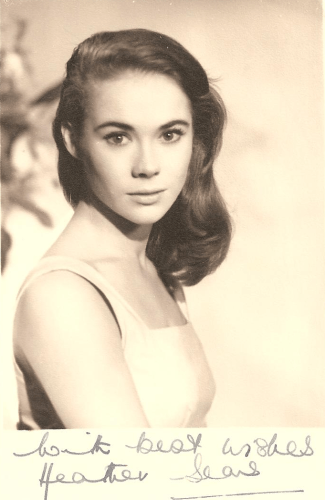

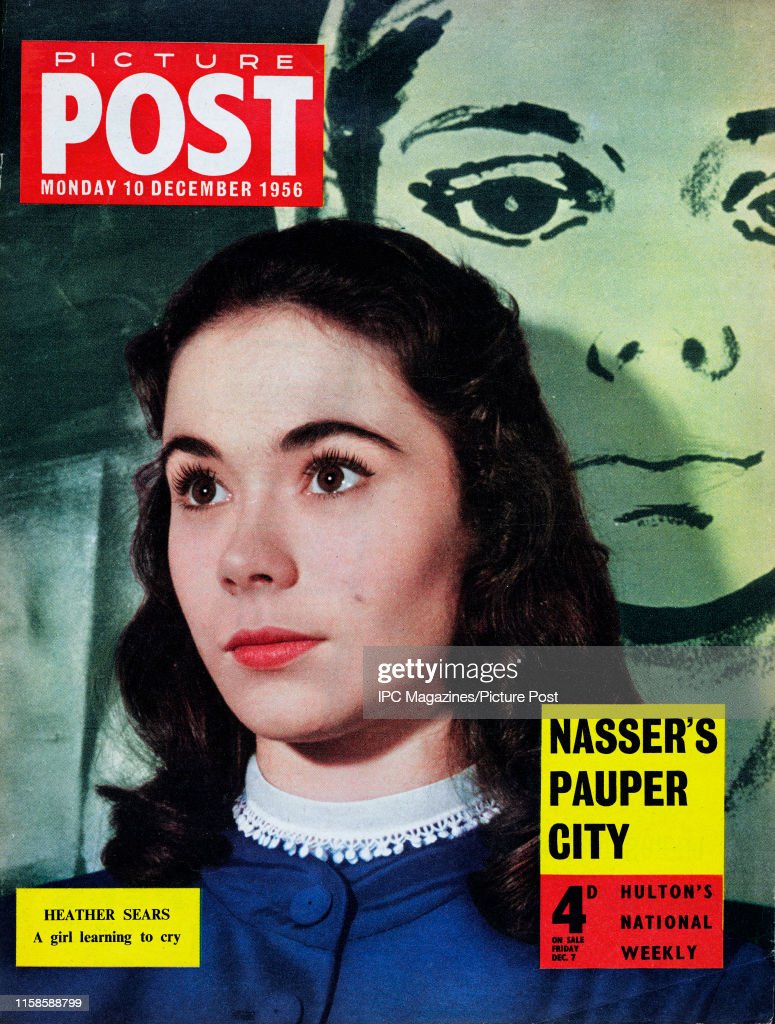

Heather Sears was very pretty and talented actress who had a sudden burst in British films in the late 1950’s which was not sustained. She made her film debut in a minor role with June Thorburn and John Fraser in 1955 in “Touch and Go”. At the age of 21 she won the title role in “The Story of Esther Costello” with Joan Crawford and Rossano Brazzi. Her most famous role was as Susan Brown opposite Laurence Harvey’s Joe Lampton in “Room At the Top”. She also starred in “Sons and Lovers” from the novel by D.H. Lawerence. Her film career had waned by the early 60’s and she concentrated on the stage with occasional roles on television. Heather Sears died in 1994 at the early age of 58.

Her “Independent” obituary:

HEATHER SEARS was a beautiful, intelligent and gifted actress with taste. The four virtues rarely come together. And she might have been a star, filling theatres and cinemas with her beguiling presence, never mind the brains, the talent or the taste, if she had not also been such a human being. It made no sense to her to try to raise a family and pursue an acting career at the same time. So the acting became increasingly spasmodic as the family grew; and that was no doubt wise of her maternally. But artistically?

Would she have risen to the top of her profession had she given up everything for art’s sake? That is the only question that can interest any serious student of acting; and the answer is probably not because her talent seemed to place her at the top from the word go.

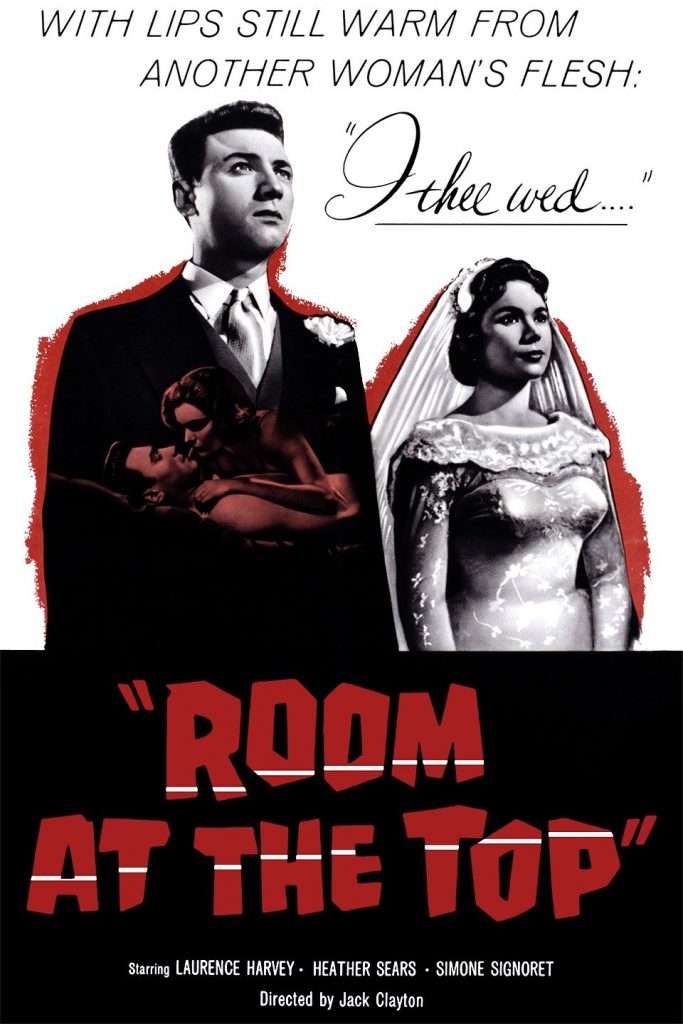

Some players are born great; others achieve greatness; and some have greatness thrust upon them. Sears struck most of us all of a heap from the start. She never seemed to have to strive. She had the looks, the charm, the personality, the warmth and, as we saw in the film Room at the Top (1958), the sense of irony to make a dullish, drippy, well-bred symbol of virginity as real and interesting as the much more sensually arresting role in the same film, played by the much more experienced Simone Signoret, as the rival object of Laurence Harvey’s social ambition and sexual fancy.

Would her acting have got much better had she practised it more assiduously? It wasn’t just in films that she first enchanted us. At the Royal Court in its heyday she was the third Alison in Look Back In Anger (to Richard Pasco’s wrathful Jimmy and Alan Bates’ Cliff). At the same theatre she made an admirable and typically warming Agnes in Giraudoux’s one-acter The Apollo de Bellac (again with Pasco and Bates), and in a Sunday night try-out, directed by John Dexter, of Michael Hastings’s Yes – And After, she also showed herself to be a player in whom a strong future could be foreseen.

She seemed to be well on the road towards it in Julien Green’s South (Lyric, Hammersmith), in which she nearly brought off the impossibly challenging part of a devoted girl who finally understood what had been happening to her beloved when he faced up to his homosexuality; and by then the world had seen her as Joan Crawford’s adopted deaf-mute daughter in The Story of Esther Costello (1957), and as Miriam Lievers in the film Sons and Lovers (1960).

So there was no doubt of it. Sears was a serious and compelling actress, but motherhood and family life intervened and in the next decade, though she worked in the film studios from time to time, she acted on the stage notably only twice. At Chichester she was the kitchenmaid in Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle, bringing up a child she had rescued from cruelty until its mother came to claim it; and in the West End she was the scattier of the two wives in Ayckbourn’s How The Other Half Loves (1970).

Not much of a record for an actress in her mid-thirties; but in the 1970s she more than made up for it when she felt free to return to the stage, even if the artistic atonement took place in that relatively unfashionable sector of the theatre – provincial rep.

You had to go to the Leicester Haymarket, one of the better-funded houses, to see her in Sophocles, Shakespeare, Farquhar, Goldsmith, Dostoevsky, Strindberg, Ibsen, Rattigan and Pinter. Just the kind of names you might expect to find in any serious-minded National Theatre’s repertoire – though she would have looked in vain for most of them on the South Bank – and just the place to prove herself the dedicated player we had suspected her to be 20 years earlier. Leicester was only an hour and a bit non-stop from St Pancras and her acting was always worth the journey, never more so than in 1979 in Ibsen’s Little Eyolf.

As the possessive, passionate wife of a man overwhelmed by guilt over the drowning of their crippled son, the actress conveyed with stillness and understatement all the pain and fear for the future of a marriage drained of warmth but sealed by cold duty. It was acting of a quality only Ibsen could provoke with his feeling for feminine character, and which only this actress in her renewed dedication to her art could, as a mother herself, deliver with such stirring, unaffected, emotional candour.

It made you feel she had indeed been born great.

Her “Independent” obituary can also be accessed here.

Article on Heather Sears from Tina Aumont’s website:

Petite and pretty with a mass of talent, the quiet and often beguiling Heather Sears had the power to shine on both stage and screen. And although she only appeared in 10 movies in her long (if sporadic) career, she managed to inject her characters with genuine warmth and emotion, leaving a haunting impression on many who saw her.

Sears was born on September 28th 1935, and, after attending drama school in London, won a contract with Romulus Films where she was mentored by director Jack Clayton. After minor bit parts in the 1955 Jack Hawkins comedy ‘Touch and Go’ and the Ronald Shiner cockney farce ‘Dry Rot’ (’56), Heather would land an early juicy role that would bring her to the attention of both the public and critics.

In 1957 Heather was hand-picked to play the title role in Jack Clayton’s production of ‘The Story of Esther Costello’, as a 15 year old girl rendered deaf, dumb and blind after a childhood accident (in a compelling opening scene). Joan Crawford was the caring socialite who takes Esther into her care and, although Sear’s performance was later overshadowed by Patti Duke’s faultless performance in ‘The Miracle Worker’, Heather was still excellent in a difficult role, and convincingly conveyed her character’s initial struggle to communicate. Though at times overly melodramatic, it was a very good movie and earned Sears a BAFTA for Best Actress, and much international praise. After filming, Heather married the movie’s art director Tony Masters, and they would remain together until his death in 1990.

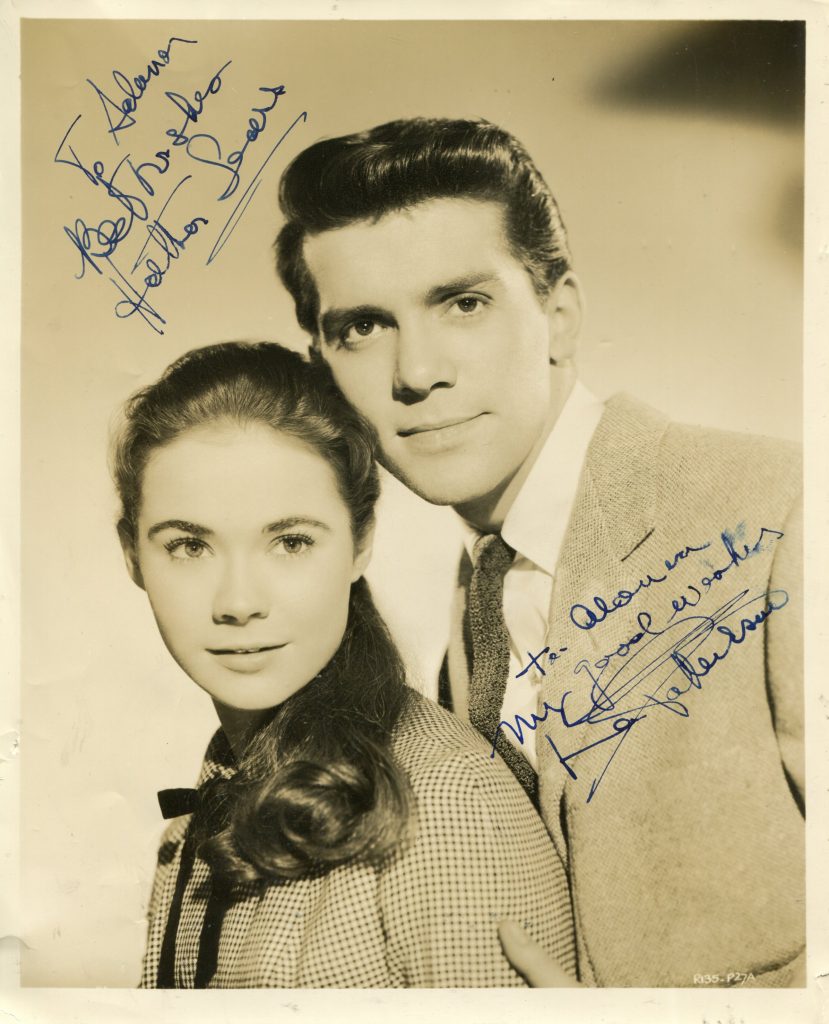

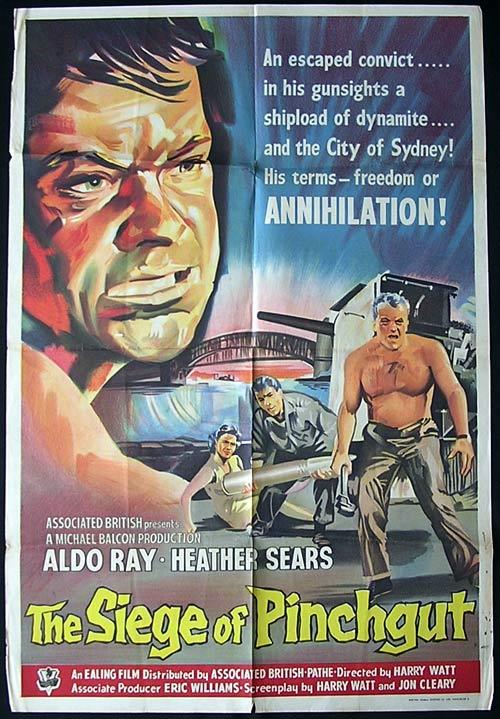

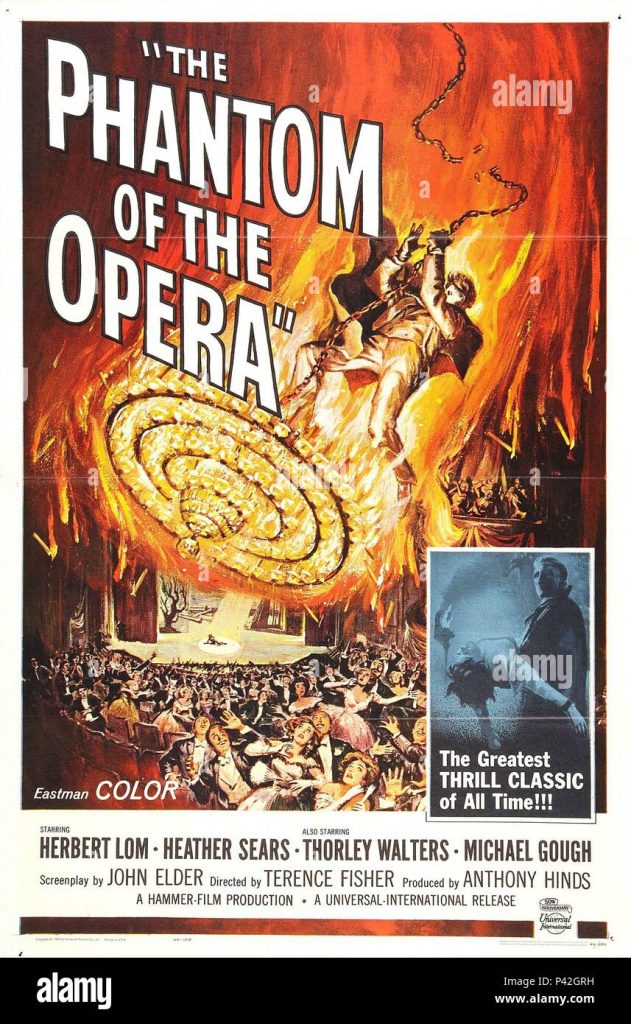

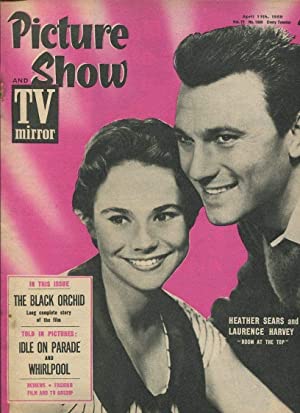

It would be Sears’ next film role though, that she is probably best remembered for, as the loving and naïve Susan Brown, the spoilt daughter of Donald Wolfit’s imposing industrialist, in Jack Clayton’s blistering drama ‘Room at the Top’. Laurence Harvey starred as Joe Lampton, an ambitious young man with big dreams, whose affair with a married woman (played wonderfully by an Oscar-winning Simone Signoret) resulted in tragic consequences. A deserved classic of British cinema, it’s still a powerful and devastating movie, and one that ushered in a new wave of realism. Travelling to Australia, Heather made the very good crime picture ‘The Siege of Pinchgut’ (’59) playing a caretaker’s daughter who’s taken hostage by Aldo Ray’s escaped convict. Largely forgotten in the UK, it remains something of a classic in Australia. Another good role came the following year in Jack Cardiff’s sensitive drama ‘Sons and Lovers’ (’60), as the academic friend of Dean Stockwell’s artistic yet browbeaten teenager. She was abducted again, this time in Hammer’s 1962 remake of ‘The Phantom of the Opera’, as the rising opera star Christine Charles, who’s fixated upon by Herbert Lom’s Phantom.

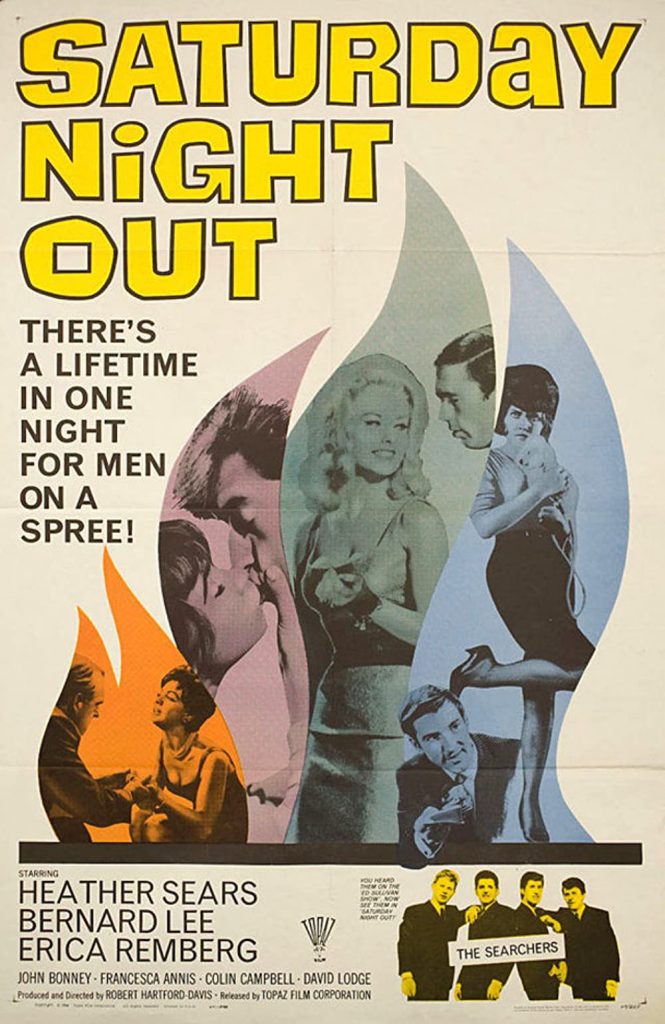

Heather’s last film role of note came in the 1964 gothic horror ‘The Black Torment’, starring as Lady Elizabeth Fordyke, the new bride of John Turner’s Sir Richard Fordyke, a Lord who has been accused of murder by local villagers. Busy raising a family, only periodic TV appearances followed, including the series ‘The Informer’ (’66-7) as disgraced barrister Ian Hendry’s wife. In the 1970’s Sears returned to the theatre, starring in both the Classics as well as plays by Alan Ayckbourn and Harold Pinter. On television, she appeared in a 1974 remake of ‘Great Expectations’, playing the orphan Biddy who befriends young Pip. After a couple of more television guest spots, Heather’s final screen role was in the obscure 1989 movie ‘The Last Day of School’.

Married to Tony Masters for over 30 years, and with 3 sons, Heather Sears sadly died of multiple organ failure, on January 3rd 1994. She was only 58. A genuine talent, Heather managed to leave her mark in some impressive Black & White pictures, and gave outstanding performances in a couple of unforgettable ones.

Favourite Movie: Room at the Top

Favourite Performance: The Story of Esther Costello