Marlene Dietrich was born in Berlin in 1901. She began her career in German silent film and then won international acclaim as Lola-Lola in “The Blue Angel” with Emil Jannings. The popularity of the film led to offers from Hollywood and Dietrich went to the U.S. in 1930. She had a contract with Paramount Studios and her first Hollywood film was “Morocco” opposite Gary Cooper. Her most famous movies include “Shangai Express” with Anna May Wong, “The Garden of Allah” with Charles Boyer and “Knights Without Armour” with Robert Donat. In later life she had a very successful career as a concert performer. She had a late career movie success with “Witness for the Prosecution” with Tyrone Power. On retirement she went to live in Paris and became reclusive in her later years. Marlene Dietrich died in 1992 at the age of 90. Her website can be accessed here.

Daily Telegraph obituary in 1992.

Celebrated for her roles in The Blue Angel and Destry Rides Again, she appeared in 50 films between 1923 and 1964. She was the last well-known survivor of the Kaiser’s Germany.

Her theme tunes – Falling in Love Again, Johnny, The Boys in the Back Room and Where Have All the Flowers Gone? – haunted generations; her rendering of Lilli Marlene became as popular as that of Lile Andersen which was the favourite of British and German troops in the Second World War.

Husky-voiced and fair-haired, with heavily-lidded eyes, she displayed a cool ‘don’t care’ expression of world-weary disillusion. In an age when stardom is transitory, she proved enduring.

Marlene Dietrich was a postmistress at dispensing her own dangerous blend of glamour and carried through life the aura of Berlin’s smoky decadence.

Blonde, Teutonic, with high-chiselled cheekbones, she mesmerised her audiences by innuendo, letting her vacant eyes drift over the room, pulling in her heavily magenta-ed lower lip, displaying all the artifice of languor.

Famed for playing prostitutes in films, her world was never one of convention. She yearned for all that was artificial.

As a singer she was a polished performer, alternatively lazy in mood and powerfully aggressive, almost paramilitary. Her delivery of Johnny was both breathy and erotic and she manipulated the microphone in a manner nothing less than sexual.

No one who saw her spectacular entrance down the winding staircase of London’s Café de Paris in the 1950s is ever likely to forget it. Sparkling from head to foot with no shortage of white mink, she did not so much descend as glide down like a serpent, disdainful, glamorous, a little threatening.

Far from modest, Dietrich relished a record of the applause at these performances. One evening she played this to Noël Coward, explaining: ‘This is where I turn to the right . . . Now I turn to the left.’ When the first side ended, she threatened to turn the record over. Coward erupted: ‘Marlene, cease at once this mental masturbation]’ Marlene Dietrich was born in Berlin on Dec 27, 1901, the younger daughter of a Prussian officer, Louis Dietrich, and his wife, Josephine Felsing, who came from a family of jewellers. She spent part of her childhood in Weimar.

Her father died in 1911 and her mother, who then married Eduard von Losch, a Grenadier colonel, played a big part in her life. She was brought up in the Germanic tradition of duty and discipline. The theatre was in her blood from the start; she worshipped Rilke, read Lagerlof and Hofmannsthal and knew Erich Kästner by heart.

She was keenly musical and learned the violin. From 1906 to 1918, she attended the Auguste Viktoria School for Girls in Berlin. At the end of the First World War, she was enrolled in the Berlin Hochschule fur Musik but stayed only for a few months.

The family soon fled to the country, where her stepfather died. In 1919, she entered the Weimar Konservatorium to study the violin. She hoped to become a professional violinist but a damaged wrist destroyed this hope.

In 1920, Marlene was back in Berlin. The next year she auditioned for the Max Reinhardt Drama School and played the widow in The Taming of the Shrew.

A string of minor parts followed. Marlene lived in virtual penury, worked in a glove factory and acted and danced. It was a depressing way of life.

In 1923, she played Lucie in The Tragedy of Love, on the set of which she met her husband, Rudi Sieber. It was by no means love at first sight but Marlene began by being in great awe of him. They married and had a daughter, Maria (born in 1925).

The marriage did not last. Sieber was overshadowed by Dietrich, who described him as a ‘very, very sensitive person’. She bought him a farm in California where he dwelt with his animals, a mistress (until she went mad), her blessing and her financial support; he died in 1976.

In the late 1920s, Dietrich acted and filmed in various productions in Berlin, including I Kiss Your Hand, Madame.

In 1930, she was discovered by the Viennese director, Josef von Sternberg, who detected in her the raw sexuality of a seductive vamp and brought her to fame in his film The Blue Angel. Von Sternberg transformed her from a rather brawny girl with the slight air of a female impersonator into a creature of glamour.

Even in The Blue Angel, as she sits on the barstool as the seductive temptress Lola-Lola, luring the salivating professor to his doom, her legs appear more well covered than is now considered fashionable. Von Sternberg recognised the conflict within her: ‘Her personality was one of extreme sophistication and of an almost childish simplicity,’ he wrote.

Originally Dietrich had been rejected for the part as ‘not at all bad from the rear but do we not also need a face?’ But then von Sternberg saw her by chance in the Georg Kaiser play ZweiKrawatten. She was gazing bored at the action on stage and he was drawn to her disdain and poise.

Despite her success, UFA did nor renew her contract and so she signed with Paramount and emigrated to Hollywood. There she made several memorable films for von Sternberg.

Morocco, in which she played a cabaret star in love with a French legionnaire (Gary Cooper), included a scene in which Dietrich, dressed as a man, plants an unchaste kiss on a girl’s mouth in a café. The film brought massive fame and Marlene contrasted the adulation she received off camera to the virtual martyrdom she endured under von Sternberg’s precise and relentless direction.

Dishonoured followed, in which she played an Austrian spy, who fixed her make-up in the reflection of an officer’s sabre and applied her lipstick while a German officer ranted at her. The firing squad then shot her dead.

She was described as a ‘vamp with brains and humour’ and was paid pounds 50,000.

Von Sternberg was harshly criticised in his later films for presenting Dietrich in a series of lavish films in which she was little more than a clothes-horse, bedecked in black lace, feathers and jewels – Shanghai Express, Blonde Venus, The Scarlet Empress and The Devil is a Woman.

These criticisms von Sternberg repudiated. Dietrich displayed a mixture of self-love and outward tenderness, her egoism and Germanic ruthlessness belied by a sweetly feminine mouth and high, serene forehead. In 1933, at von Sternberg’s suggestion, she played Lily Czepanek in Song of Songs for Reuben Mamoulian. Von Sternberg ended his association in 1935 (following which his career floundered).

He concluded: ‘When we first met, her pay was lower than that of a bricklayer and, had she remained where she was, she might have had to endure the fate of a Germany under Hitler.’ Whatever the pains of the association, it had been a rewarding one.

Dietrich’s association with von Sternberg was the subject of an analytic study, In the Realm of Pleasure, concerning von Sternberg, Dietrich and the ‘masochistic aesthetic’.

The author, Gaylyn Studlar, concluded: ‘Dietrich is frequently mentioned as an actress whose screen presence raises questions about women’s representation in Hollywood cinema. She has also acquired her own cult following of male and female, straight and gay admirers.

‘The diverse nature of this group suggests that many possible paths of pleasure can be charted across Dietrich as a signifying star image and across von Sternberg’s films as star vehicles.’

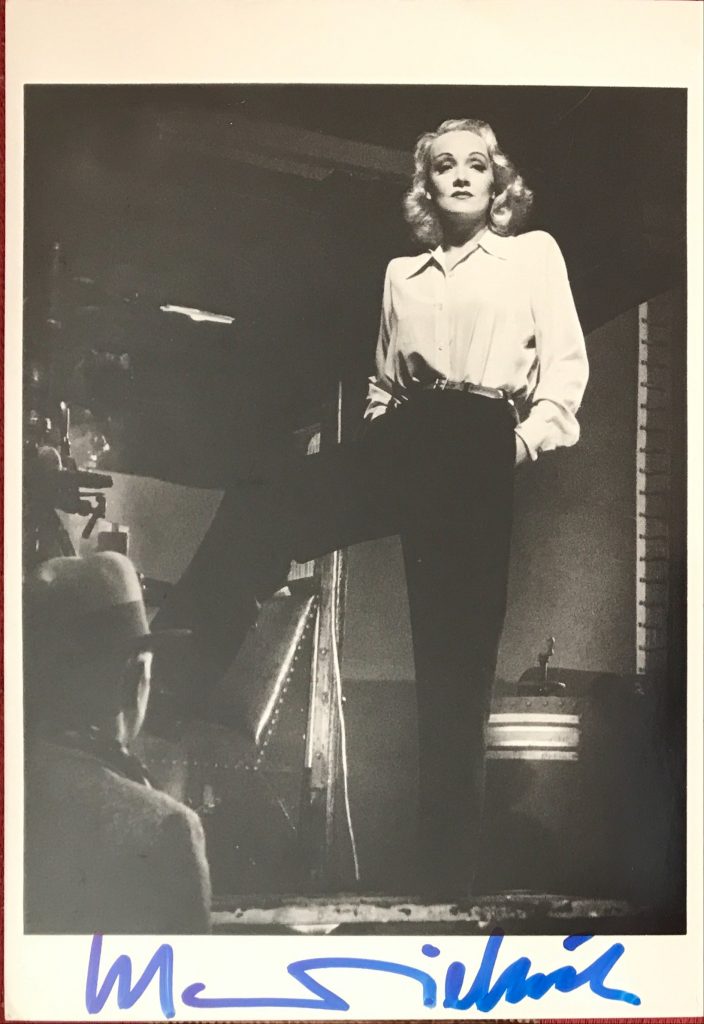

Kenneth Tynan also pursued this theme in a celebrated profile of the star: ‘She has sex but no particular gender. Her ways are mannish: the characters she played loved power and wore slacks and they never had headaches or hysterics. They were also quite undomesticated. Dietrich’s masculinity appeals to women and her sexuality to men.’

Inevitably, the arrival of Dietrich was seen in Hollywood as that of a blonde Venus in the vanguard of Garbo, the Sphinx. There was some similarity in the style of the films (Mata Hari then Dishonoured, Queen Christina in comparison to The Scarlet Empress).

It was generally accepted that if any rivalry existed, Garbo won without effort. A remarkable composite photograph by Steichen exists portraying Dietrich and Garbo together but, if they ever met, it was an unsatisfactory encounter.

At the behest of Mercedes de Acosta, with whom both were romantically linked, they made the wearing of slacks by females fashionable. In 1936, Dietrich starred opposite Cary Grant in Desire and then played in The Garden of Allah, Knight Without Armour and Angel. In 1939, came her energetic portrayal of Frenchy, the Wild West saloon keeper in Destry Rides Again.

This classic included Dietrich’s spirited wrestling with James Stewart, and she gave tongue to the evocative song The Boys in the Back Room, while bestriding the bar.

In the early years of the Second World War, there were more films for more directors. Meanwhile, in Germany Hitler destroyed all but one copy of The Blue Angel and went to great lengths to try to lure Dietrich to his cause.

But in 1943 she assumed the honorary rank of Colonel in the American Army and made radio broadcasts and personal appearances on behalf of the American war effort. In 1944, she joined the United States Overseas Tour and paid extensive visits to the Allied troops in Europe.

Dressed in an elegant version of military uniform, her blonde hair as flowing and feminine as ever, her mission was to boost morale, to entertain and to encourage Allied victory. There is film footage of Dietrich greeting the Fifth Army with a jaunty ‘Hello, Boys]’ and congratulating them on their singing.

Jean-Pierre Aumont was a fellow actor she met in wartime Italy and who was destined to become a lifelong friend. He summed up her role: ‘In the eyes of the Germans, she is a renegade who serves against them on behalf of the American Army. They wouldn’t hesitate to shoot her.

‘Under the veneer of her legendary image, Marlene Dietrich is a strong and courageous woman. There are no tears. No panic. In deciding to go sing on the field of battle, she knew the risks she was taking and assumed them courageously, without bragging and without regrets.’

Dietrich’s line was that her former countrymen had fallen under the tyranny of Hitler and that this evil must be removed. Jean Cocteau was sad that in the early post-war years she never sang Falling in Love Again in the original German in fear of being associated with the Germany of 1940.

Of her war-work, she said: ‘This is the only important work I’ve ever done.’

The elder sister Dietrich never mentioned (Elisabeth) was incarcerated in a prisoner-of-war camp in Germany and her mother died in 1945. Marlene returned to America after the cessation of fire. She was awarded the Legion of Honour and the American Medal of Freedom.

Dietrich made many further films, including Billy Wilder’s A Foreign Affair, Hitchcock’s Stage Fright, and Witness for the Prosecution for Wilder. In this she played two roles, one a Cockney, her unlikely accent coaxed by a despairing Noël Coward.

She also appeared in Touch of Evil for Orson Welles and Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg opposite Spencer Tracy. In 1956, she contributed a memorable cameo to Mike Todd’s Around the World in 80 Days, perched on a stool Destry-style.

Dietrich also ran her own radio spy series, Café Istanbul, on America’s ABC Network. But it was as a singer that her later career blossomed.

By now in her early 50s, she began by compèring a Madison Square benefit arranged by her daughter. Out of a wish not to sit on an elephant, she took the role of ringmaster in top hat, tailcoat and tights. This white tie look was to be a lasting trademark.

Dietrich made her debut at the Sahara, Las Vegas, in 1953 and the next year took London by storm at the Café de Paris. She was always glamorously dressed and accompanied by an orchestra of 22 men.

Thereafter she made long tours all over the world, invariably accompanied by Burt Bacharach. Though she relied heavily on Bacharach, whom she described as her ‘arranger, accompanist and conductor’, she was always her own agent.

In 1960, Dietrich made a controversial return to Germany where she was greeted by a bomb on one side and Willy Brandt on the other. She toured Israel the same year and visited Russia in 1964.

In 1967, she made her debut on Broadway. Dietrich’s one-woman show carried on until the late 1970s when accidents recurred with startling frequency.

She broke so many bones that comedians used to mimic her, singing ‘Falling off stage again . . .’ Finally, she broke her thigh in Sydney in 1976 and gave up.

As Dietrich grew older, she seemed to defy the passing years. Cecil Beaton watched her 1973 Drury Lane performance on the television and dissected her ruthlessly: ‘Somehow she has evolved an agelessness.

‘The camera picked up aged hands, a lined neck and the surgeon had not be able to cut away some little folds that formed at the corners of her mouth.

He had, however, sewn up her mouth to be so tight that her days of laughing are over . . .’

Beaton admired her dress, her ‘huge, canary yellow wig’ and her showmanship: ‘She has become a mechanical doll, a life-size mannequin. The doll can show surprise, it can walk, it can swish into place the train of its white fur coat. The audience applauds each movement, each gesture, the doll smiles incredulously – can it really be for me that you applaud? ‘Again a very simple gesture – maybe the hands flap – and again the applause, and not just from old people who remembered her tawdry films but the young find her sexy.

She is louche and not averse to giving a slight wink, yet somehow avoids vulgarity.

‘Marlene is certainly a great star, not without talent, but with a genius for believing in her self-fabricated beauty, for knowing that she is the most alluring fantastic idol, an out-of-this-world goddess or mythological animal, a sacred unicorn.’

Beaton attributed her success entirely to perseverance and an ability to magnetise audiences into believing she was a phenomenon, just as she has mesmerised herself into believing in her own beauty. An experienced critic of such creatures, Beaton could find no chink in her armour.

Despite himself, he sat enraptured. He almost concluded that she was ‘a virtuoso in the art of legerdemain’ but then he wrote: ‘ ‘You know me,’ Marlene is fond of saying. Nobody does because she’s a real phoney. She’s a liar, an egomaniac, a bore.’

It was to the music of Falling in Love Again that Dietrich bade the world a spirited farewell in Paris: ‘Je dois vous dire adieu, parce que c’est fini.’

Sparkling in sequins and surrounded by flowers, she glided off stage, bowing low, clenching and unclenching her hands as though casting a spell over the audience, returning for more applause and, finally, clinging to the curtain.

At length, she disappeared behind it by degrees with a parting wave to the besotted audience.

Her last film appearance was in 1978 as the glamorously veiled Baroness von Semering in Just a Gigolo with David Bowie, in which she intoned the title song. She was still high cheekboned but the power had gone from her voice.

The myth of Marlene lived on and the rumours of her loves – with Jean Gabin, Ernest Hemingway and others – were long discussed. She moved between her apartment in the Avenue Montaigne and a flat at 993 Park Avenue. In her ABC book, she declared: ‘A man at the sink, a woman’s apron tied around his waist, is the most miserable sight on earth.’

As for pouting, she wrote: ‘I hate it but men fall for it, so go on and pout.’

Dietrich was not only a star. She was a nurse to many friends, a cook to her grandchildren and, in reality, there was much about her that was hausfrau-ish. Kenneth Tynan described her as ‘a small eater, sticking to steaks and greenery but a great devourer of applause’.

She was the author of an unforthcoming book of memoirs, in which she finally rejected the world: ‘What remains is solitude.’

In the years of her retirement, there were rumours that Dietrich was drinking or in a home. Ginette Spanier, the directrice of Balmain, suggested that she dine in a neighbouring restaurant and that they have a tame photographer on hand to record her evening out to show that all was well.

Spanier worried that Dietrich might not be equal to the challenge but, on the night in question, the Teuton emerged from her building as glamorous as ever. When the photographer approached, she pushed Spanier firmly out of the picture to ensure she was portrayed alone.

Every time the world thought they had heard the last of her, she was either photographed at an airport or issued a curious statement to the press.

Then, in 1984, she agreed to make a documentary film with Maximillian Schell (her co-star in Judgment at Nuremberg), without appearing on camera, her voice overriding the visual images in a mixture of German and English, ‘three days this and three days that,’ as she put it.

In that film, she was dismissive of many of her old films, judging them ‘kitsch’; she rejected women’s lib as ‘penis envy’; maintained that women’s brains weighed only half a man’s and declared: ‘Well, I’m patient and I’m disciplined and I’m good.’

In extreme old age, she remained in her Paris apartment and many friends from the past were bitter when their telephone calls were answered by Dietrich pretending to be the maid.

Jean-Pierre Aumont was a favoured friend, who submitted to many hours of telephone conversation, and occasionally took her out to tea at the Plaza Athenee opposite her apartment.

She rose at six, could sometimes be seen early in the morning, draped in Indian shawls, walking a tiny dog, accompanied by a minder. But officially she was never seen and, after Garbo’s death, became the world’s most celebrated recluse, existing on a diet of champagne, autographs, reading and the telephone.

Yet the lingering image must forever be her descent of the Café de Paris staircase, the club specially adorned with cloth of gold on the walls and purple marmosets swinging on the chandeliers and Noël Coward intoning his gracious, if clipped, introduction: Though we might all enjoy Seeing Helen of Troy As a gay cabaret entertainer, I doubt that she could Be one quarter as good As our lovely, legendary Marlene