Celia Johnson tribute in “The Guardian”

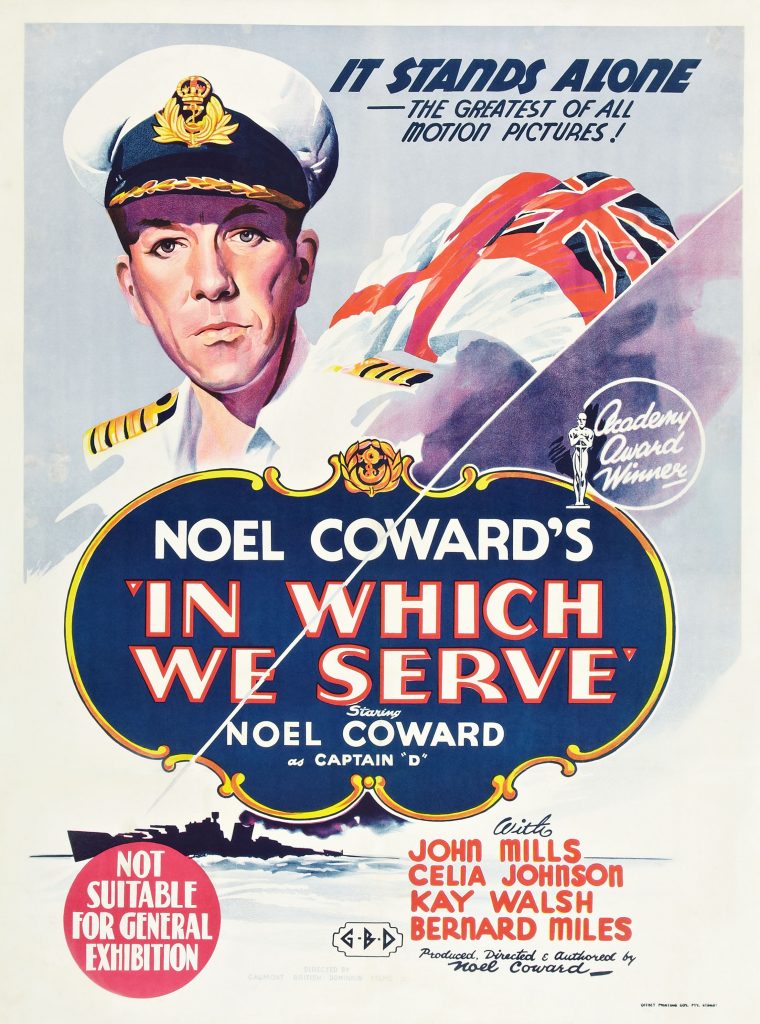

Who can ever forget Celia Johnson in her silly hat rushing around the home counties train stations in post-war Britain trying to escape the romantic inclinations of Trevor Howardin “Brief Encounter”. She was nominated for an Acadmey Award for her performance. Primarily a stage actress she made relatively few films but some of them are now regarded as classics including ther afore mentioned “Brief Encounter”, “This Happy Breed”, “A Kid for Two Farthings” and “The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie”. Celia Johnson died in 1982. She was a consummate actress.

“Guardian” tribute:

Celia Johnson died in her prime – at the age of 73. There was no other actress on the English stage whose career reached its zenith, a luminous Indian summer on both stage and television, in middle and old age. She defined to perfection a social type occupying the entrenched territories of middle and upper-middle class gentility, whose crisp, understated manners and stringent lack of sentimentality she conveyed to the manner born. Yet she did not simply serve as a comprehensive guide-book to or map of a contracting portion of England. She incarnated qualities both of restraint and of passion; she knew everything about high English comedy whose airs of distraction and self-absorbed remoteness she conveyed so sharply in Coward’s Hay Fever and Ayckbourn’s Relatively Speaking; more surprisingly she was able in old age to act indelibly roles of high tragic velocity and pathos, and obliterated all sentimental nuances from the plays of William Douglas-Home.

It was after the 1945 film Brief Encounter where, grief-struck but tight-lipped in a railway station, she gave a regretful adieu to adultery without savouring its joys, that she became a surprise star. Who then would have imagined this light elegant comedienne, who had won the admiration of du Maurier in the Thirties, could convey all the nuances of erotic passion with such conviction and discriminating restraint? For in the first 15 or so years of her theatrical career, which had begun in 1928, she had played a succession of bright young things in period pieces. Brief Encounter brought the theatrical reward of St Joan at the Old Vic. The critic Kenneth Hurren, applauding the “immensely moving” nature of her performance, noted with approval that she had chosen to stress the saintly rather than the peasant-like aspect of the rare girl. It was to be followed three years later by an Old Vic Viola and the quietly suffering Olga in Three Sisters, to Ralph Richardson’s Vershinin.

It seemed as if she were poised to become one of our leading classical actresses, discarding the light comic roles with which she had earlier dealt. But it was not to be. She had married the author and explorer Peter Fleming, and had three children. Home and domestic life exerted a greater hold upon her than the theatre: she told me when I talked with her a fortnight ago that she never really enjoyed acting on stage and submitting herself to the rigour of nightly performance.

Throughout the Fifties and the early Sixties, she was fitfully and briefly seen on stage. But Laurence Olivier, never particularly willing to enlist players of his generation to the National, called her in 1964 to play opposite him as the neurasthenic Mrs Solness in Ibsen’s Master Builder. Her parched, wrenching performance of the woman was akin to an announcement of her unused powers. She had arrived again. Michael Billington was among those who praised her first Shakespearian performance for 20 years, applauding the way in which she was “not the usual wilting voluptuary but a distraught, untidy maternal figure caught up in events beyond her comprehension.” She regretted, she told me, that she had not played more Shakespeare. John Gielgud, a great admirer, suggests that a most unsuccessful early performance as Juliet damaged her chances of being such an ingenue.

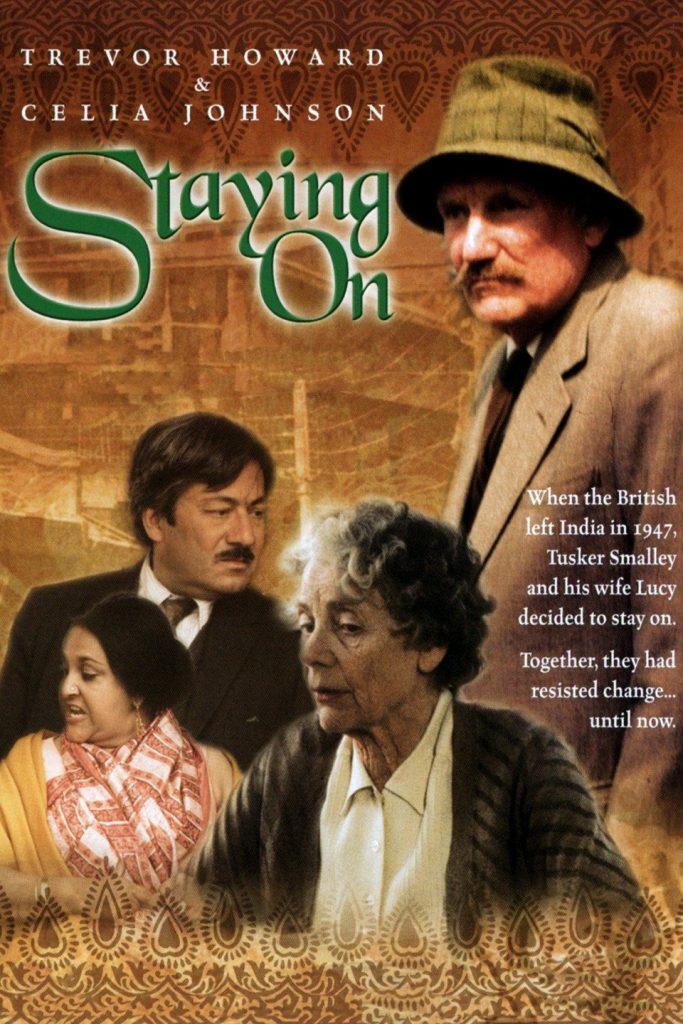

In the last decade also she became quite simply the finest television actress of her generation, coming to the medium with huge enthusiasm and scaling down her performance to comply with the range and subtleties of the screen. Her Mrs Alving in Ghosts, Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont, the wife in Graham Green’s The Potting Shed, and opposite Trevor Howard again in an adaptation of Paul Scott’s Staying On were quite remarkable for their vehement emotional clarity and tragic intimations.

The above “Guardian” tribute by Nicholas de Jongh can also be accessed online here.