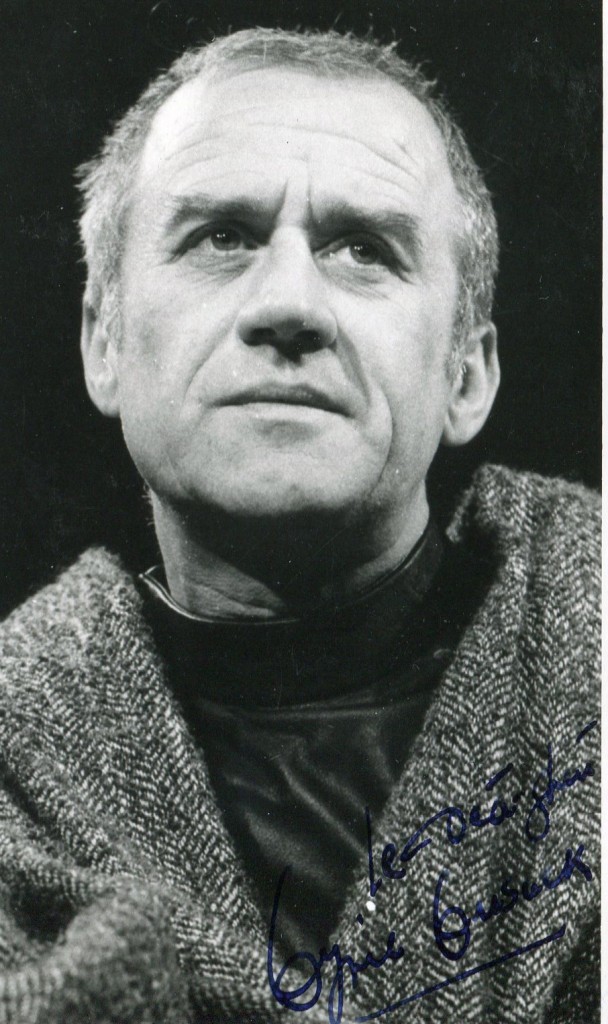

Cyril Cusack obituary in “The Independent”

Cyril Cusack was one of the great Irish actors of theatre and film. He was born in 1910 in fact in South Africa where his parents who were actors were touring in a play. He joined the famed Abbey Theatre in 1932 where he remained until 1945. He acted in over sixty productions and became a particular exponent of the work of Sean O’Casey. He formed his own production company in 1947. His first film was as a child in the 1918 silent film “Knocknagow”. His film career highlights include “Odd Man Out”, “THe Small Back Room”, “Gone to Earth”, “The Rising of the Moon” and “True Confessions”. This film he made in the U.S. in 1981 with Robert De Niro and Robert DuVal. His last stage performance was just a few years before his death where he appeared in “Three Sisters” with his own daughters Sinead , Sorcha and Cusack. His other daughter Catherine Cusack is also an actress. Cyril Cusack died in London in 1993 at the age of 82

.His “Independent” obituary:

ALL that was ever meant by the Irish theatrical tradition in the 20th century was embodied in the life of Cyril Cusack. Soft-voiced, thin-lipped, small-built, fey or sinister, gentle or chilling, poetical, musical, rueful, shy, he was by nature a quietist.

Yet he waved the banner of Irish drama with a loud loyalty to his beloved forebears, Shaw, Boucicault, Synge, O’Casey. He was born abroad, in South Africa in 1910, to an Irish father who was serving in the mounted police, and a cockney mother. But no one learnt better to understand the value and the vicissitudes of Irish fit-ups, those roving companies that strayed from village to village on a once-nightly basis.

He was a boy when his mother’s partner, the Irish actor Brefni O’Rourke, whom he later came to regard as his father, took him on. Cusack graduated in his twenties to the Abbey, Dublin. He played in over 65 of its productions in the early Thirties. He formed his own troupe, the Gaelic Players; and just before the Second World War gave Londoners a taste of his quality.

Not in the West End, of course. But at the minuscule Mercury in Notting Hill Gate, and at the now vanished ‘Q’ on Kew Bridge. Fringe productions we might call them now, but they drew the leading critics of the day to The Playboy of the Western World and The Plough and the Stars.

Here was an actor to reckon with: a melancholic, mischievous, courteous and so arrestingly Celtic, so steeped in his authors, that his Christy Mahon in Synge’s masterpiece – brimming with naive, elfin charm – and his young Covey in O’Casey’s tragi-comedy – a bantam-cock of impertinence – tingled with life and fun and finely controlled expressiveness.

They were to become his best- known parts. He had been playing them for years in Ireland, but they lit up those small west London stages: and even when he made a reputation in other roles, as the dying Louis Dubedat for instance in The Doctor’s Dilemma which brought him into the West End a few years later opposite Vivien Leigh, it seemed as if something of the Covey and of the Playboy informed his characterisation.

He loved Shaw and Shavian parts, and it grieved him as much as it grieved his admirers when on St Patrick’s Day 1942, a fortnight after the opening of The Doctor’s Dilemma, his acting went, to say the least, disturbingly fuzzy. He started introducing into Shaw’s dialogue lines from The Playboy of the Western World – having ‘dried up’, it was the only part he knew he could speak in a crisis – and his mind went blank.

Vivien Leigh also became confused; and the curtain had to come down. Whatever the facts behind a legendary occasion – had Cusack made too much of St Patrick’s Day far from home as the Blitz proceeded? was the wartime whisky bad? had he also got his understudy drunk? – both actors were dismissed. Cusack returned to Dublin to run the Gaiety Theatre with plenty of Shaw, Synge and O’Casey, including the premiere of O’Casey’s The Bishop’s Bonfire (1955).

He played Hamlet. He created a stir in Paris with his production of The Playboy, and in 1960 he won the International Critics Award for his productions at the Theatre des Nations of Arms and the Man and Krapp’s Last Tape. He also worked for the Royal Shakespeare Company and the new National Theatre, but it was his acting as Conn in the Abbey’s revival of Boucicault’s The Shaughran in a World Theatre Season at the Aldwych which proved his main achievement at the time because it provoked a most profitable revival of British interest in Boucicault which was to last for decades.

Cusack served the Dublin Theatre Festival faithfully every autumn. If his own version of The Temptation of Mr O (from Kafka) brought out his whimsicality unduly, his Gayev in The Cherry Orchard was a real charmer: and Londoners were grateful to be able to see his famous Fluther Good in The Plough and the Stars, at the Olivier Theatre in 1974, and his wonderfully sly and insinuative style as The Inquisitor in Saint Joan.

Back at the Abbey in the 1980s he was as moving as he had ever been as the father in Hugh Leonard’s autobiographical A Life, especially at the end when he whirled his umbrella at the audience, smiled wanly and with infinite pathos strolled off stage.

He never ceased to make films either in Britain or Hollywood because he was by nature a reserved actor with a marvellous eye for the telling detail. He seemed to specialise in modest little men: thoughtful, repressed, fey clerks, drunks, priests, dreamers.

His starving boy by the roadside in his first film, Knocknagow (1917), is a collector’s item, but his screen personality insinuated itself more strikingly into the atmosphere of Odd Man Out (1947), The Man Who Never Was (1956), The Waltz of the Toreadors (1962), The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965), Fahrenheit 451 (1966), The Taming of the Shrew (1967), The Day of the Jackal (1973) and True Confessions (1981).

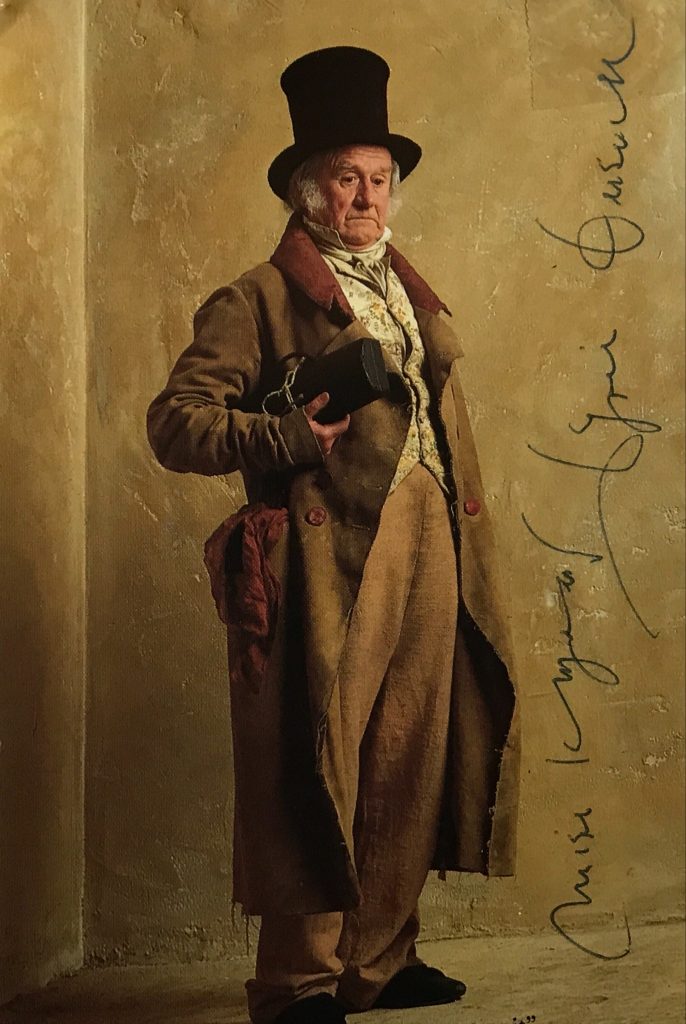

Small parts, of course, but apt to steal their scenes, though I never saw scenes more stirringly or comically stolen than at the Royal Court, in London, in 1990 in a transfer from The Gate, Dublin, of Adrian Noble’s staging of The Three Sisters.

Cusack was the last of the great Irish actor-managers and the father of a theatrical family, and the women of the title in The Three Sisters were played most affectingly by three of his talented children, Sorcha, Niamh and Sinead. But as the drunken army doctor Chebutykin, Cusack himself, with his asides and his sniffs, his murmurs and his stares, his timing, and his wry, ruminative smile, stole hearts with the subtlety and truth of his under-playing.

His “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.

TCM overview:

Gifted Irish stage performer, born in South Africa who made his film debut in 1917’s “Knocknagow”, but did not come into his own as a strong screen character actor until 1947 with Carol Reed’s “Odd Man Out”. With his quirky features, playful authority and an elfin face that sometimes registers melancholy or stern morality, Cusack most often portrayed clerics (“My Left Foot” 1989) but in “The Spy Who Came in from the Cold” (1965), he played the spy chief and in Truffaut’s “Fahrenheit 451” (1966), the book-burning fire chief. One of the most acclaimed stage actors of his generation, Cusack was famous for his association with Ireland’s national theater, the Abbey; he was at various times also affiliated with Old Vic and the Royal Shakespeare Company. Cusack also performed on Broadway, as in the memorable 1957 staging of Eugene O’Neill’s “A Moon for the Misbegotten” in which he starred opposite Wendy Hiller. Active in theatre administration and production as well, he managed the Gaity Theater in Dublin for a while in the 1940s and founded his own Cyril Cusack Productions in 1944. He is the father of actresses Sinead, Niamh and Sorcha Cusack with whom he co-starred in the 1990 Gate Theater of Dublin’s production of “The Three Sisters”.