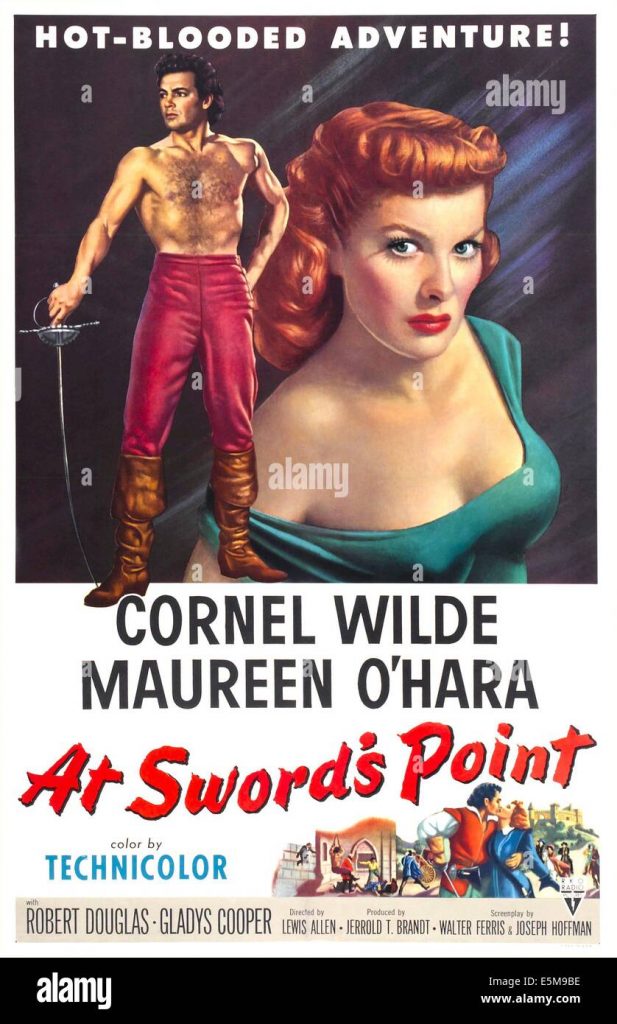

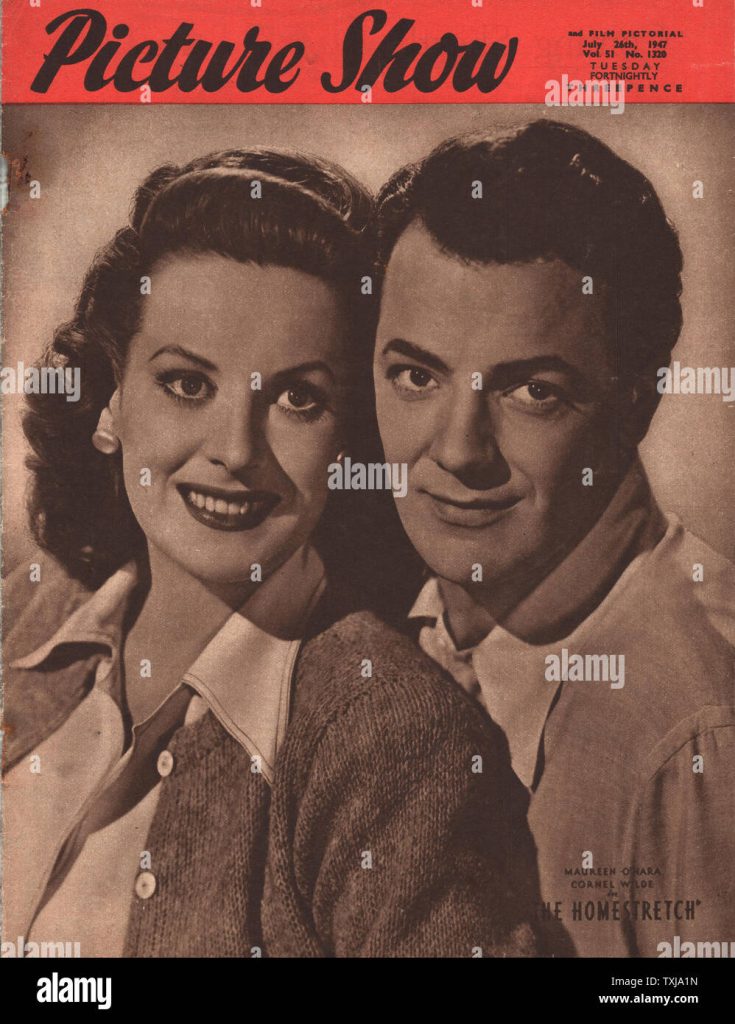

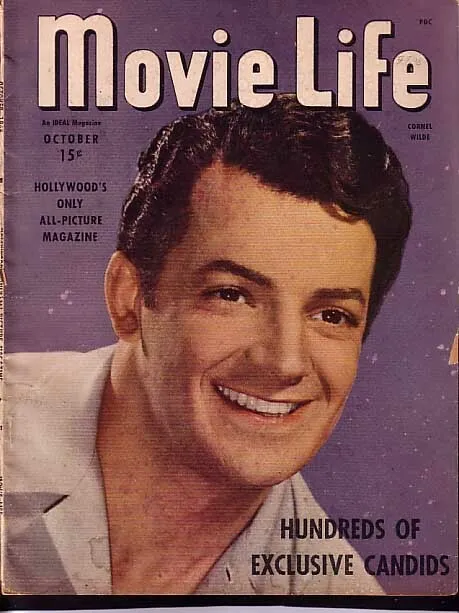

“Cornel Wilde became a competent producer/director/actor, but for years he was a sort of male Maureen O’Hara, confined to medium-budget swashbucklers and action melodramas. Like her, his acting career was at it’s peak in the 40s but unlike her, his charm was limited. Ditto his acting ability. In his marshmallow period, this hardly mattered but in the harsher days of the 50s he had to struggle. It is much to his credit that he staved off oblivion by becoming a director” – David Shipman in “The Great Movie Stars – The International Years” (1972).

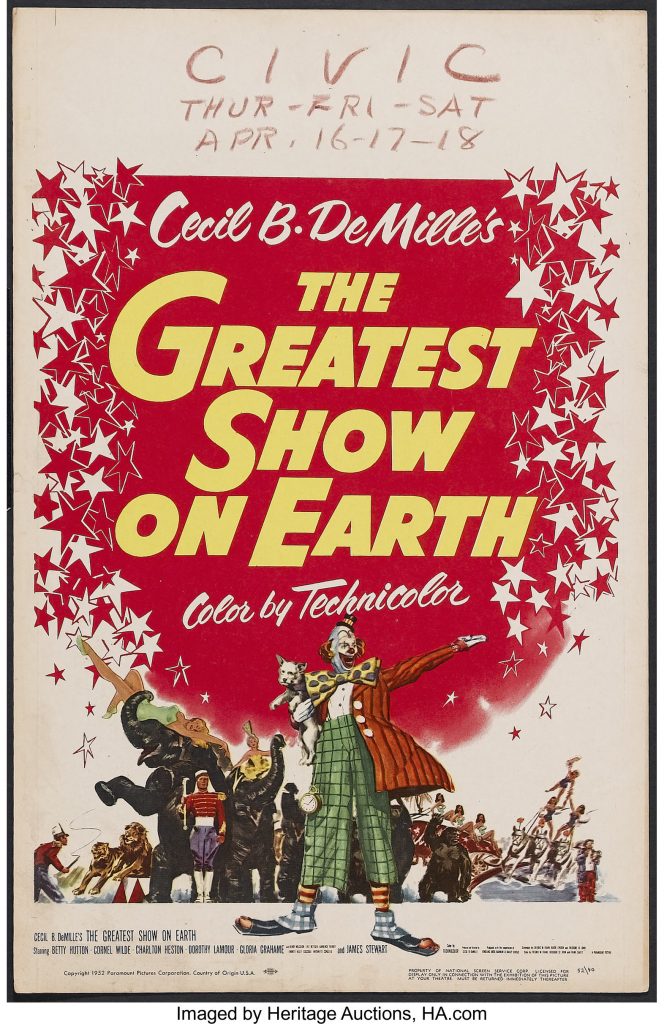

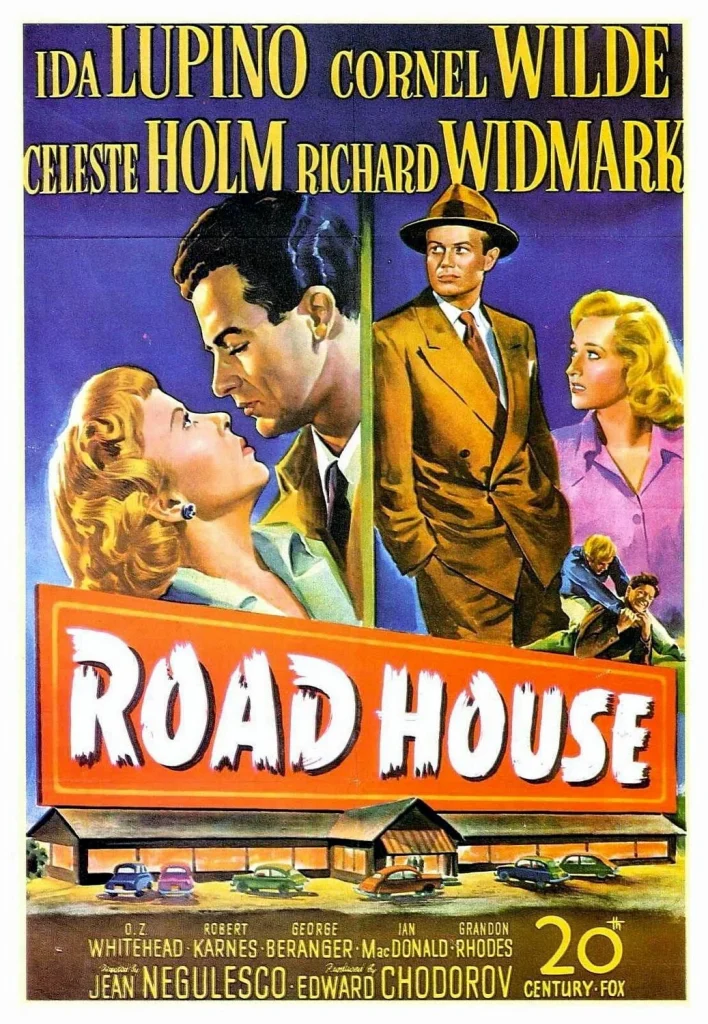

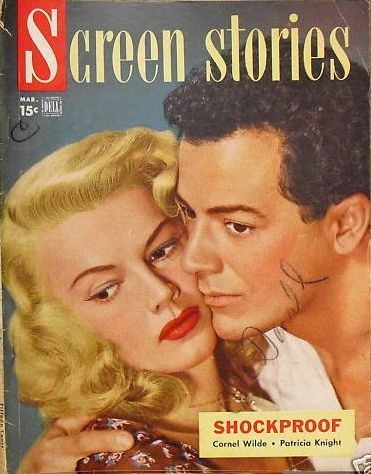

Cornel Wilde was born in 1912 in Hungary. The family moved to New York and he attended college in the city. Laurence Oliver cast him in 1940 in his production of “Romeo and Juliet” with Vivien Leigh. Wilde played the role of Tybalt. He was offered a Hollywood contract. He played many small roles until in 1945 he was cast as Chopin in “A Song to Remember” with Merle Oberon as George Sand. The film was a huge success and Wilde went on to make “Road House”, “The Greatest Show on Earth”, “Leave Her to Heaven” and “Shockproof” among others. Cornel Wilde died in 1989 at the age of 77.

His obituary in “The Los Angeles Times”:

Cornel Wilde, whose athletic abilities first brought him to Hollywood and whose elegant physique, good looks and dramatic talent kept him there for nearly 50 years, died in Los Angeles early Monday.

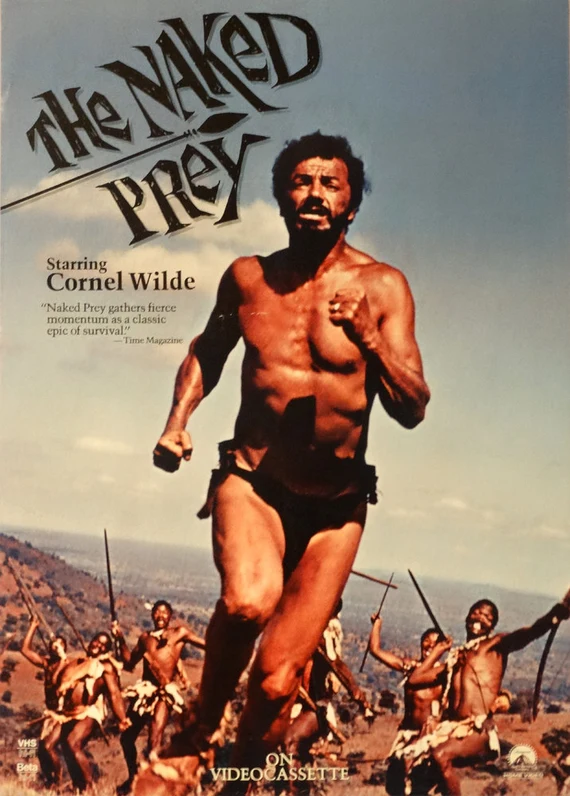

Wilde, whose film portrayals ranged from the romantic composer Frederic Chopin in “A Song to Remember” (for which he received an Academy Award nomination) to a hunter being tracked down by bloodthirsty African tribesmen in “The Naked Prey,” which he also directed, was 74. Wilde, who was admitted to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center on Sept. 2 suffering from leukemia, died shortly after midnight, said hospital spokeswoman Paula Correia. His son, Cornel Wilde Jr., and daughter, Wendy, were at his side.

During his long and varied career, which spanned the years 1940 to 1987, the aristocratic actor, writer and director was involved in more than 50 movies. “I realized long ago that I could not depend on luck to bring me success,” Wilde once said. “I worked hard, extra hard to improve my chance by increasing my abilities and my experience. It was my goal to accomplish, in my life, something of value and to do it with self-respect and integrity.”

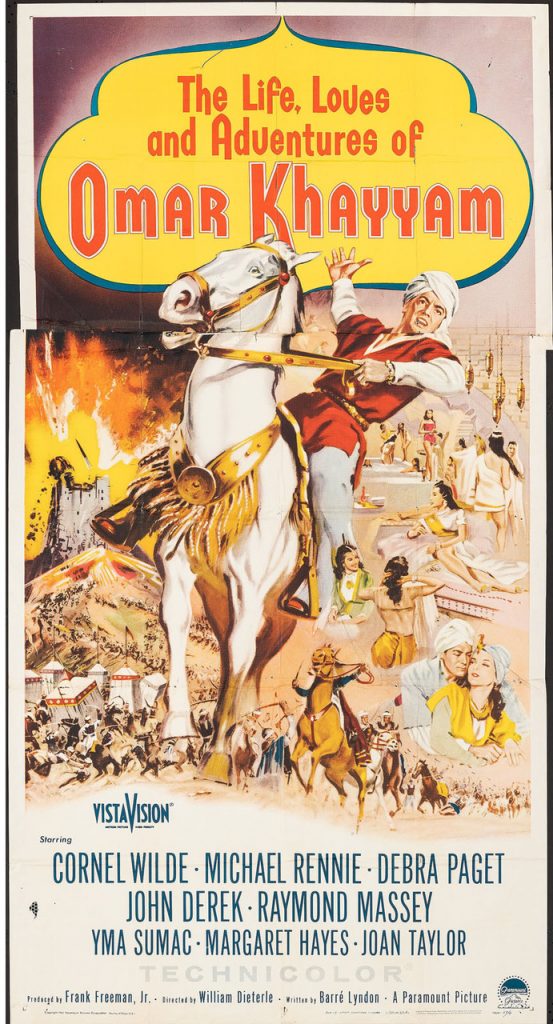

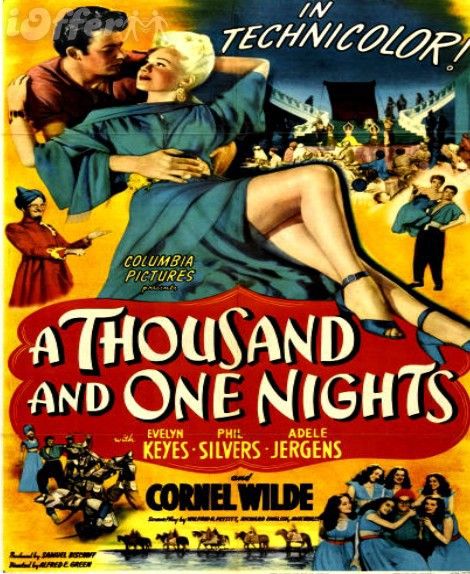

He made one of the first films ever dealing with environmental pollution (“No Blade of Grass” in 1970) and portrayed Revolutionary War spies, Omar Khayam, Constantine the Great, Robin Hood’s son and aesthetic protagonists ranging from the consumptive Chopin to the eccentric Lord Byron. He moved from studio to studio in quest of satisfying roles and from in front of the camera to behind it when he couldn’t find producers and directors who agreed with his point of view.

“Acting is not just ‘another day, another dollar,’ ” he told columnist Hedda Hopper as long ago as 1954. “If I hate a script or think it’s foolish or in bad taste, I’m miserable.”

A linguist with a command of Hungarian, French, German, Italian and Russian, he was born in New York City to Hungarian-Czech parents but spent much of his formative years in Europe, where he became interested in fencing.

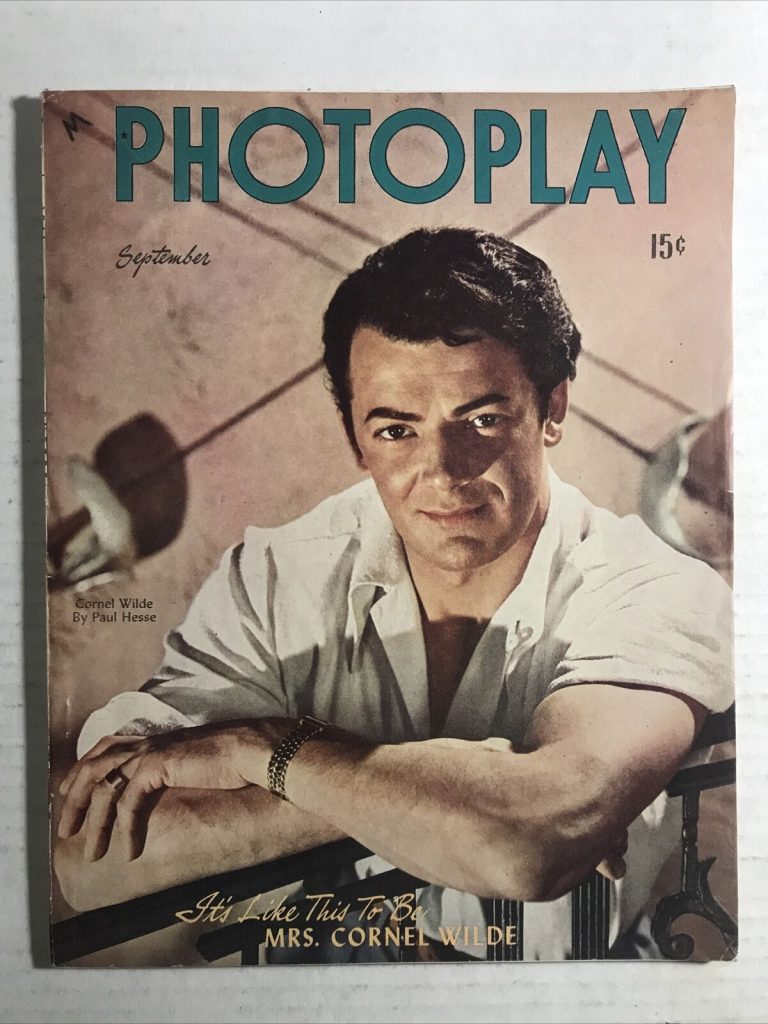

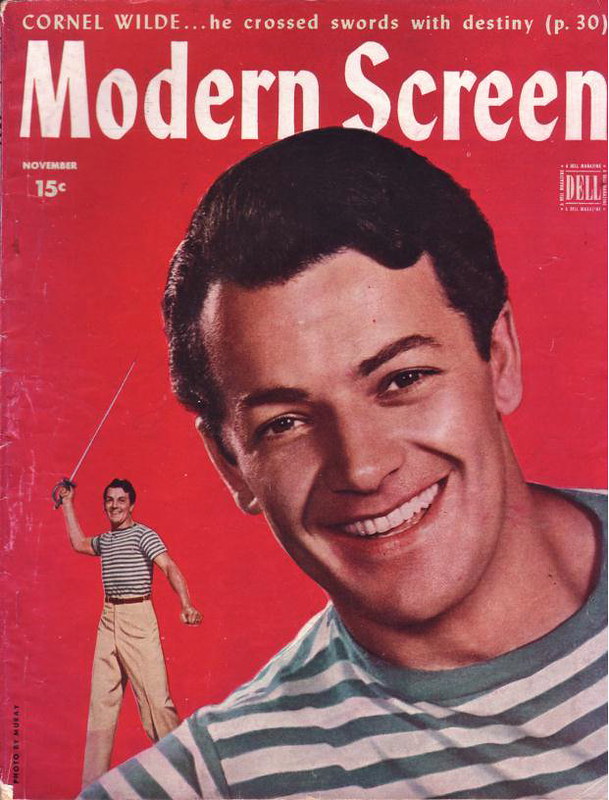

After his Hungarian father, who traveled Europe for a cosmetics firm, finally settled in the United States in 1932, Cornelius Louis Wilde studied at City College of New York, intending to become a physician. In 1935, he won a scholarship to Columbia University, where he hoped to study surgery but instead abandoned his classes after appearances in several stock theater companies whetted his interest in things dramatic. He also gave up his membership on the U.S. fencing team that was headed to the 1936 Berlin Olympics; yet it was his skill with a foil that would eventually lead him to Broadway and then to motion pictures.

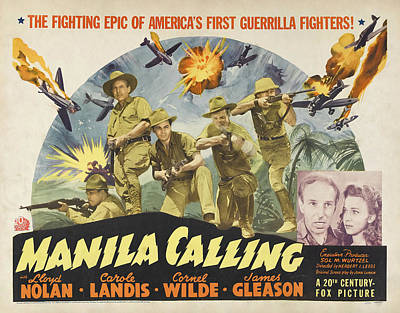

After several modest stage productions in New York and on the road, he was hired as a fencing instructor and featured player (Tybalt) in the Laurence Olivier-Vivien Leigh stage production of “Romeo and Juliet.” Because of the stars’ movie commitments, some of the play’s rehearsals were held in Hollywood and Wilde was offered, and accepted, a Warner Bros. contract. Originally he was cast as a heavy or lead in B pictures, but his dark good looks and a change in studios (to 20th Century Fox) earned him feature parts in such pictures as “Lady With Red Hair” in 1940 and “High Sierra,” in 1941, where he played an apprentice hoodlum to Humphrey Bogart.

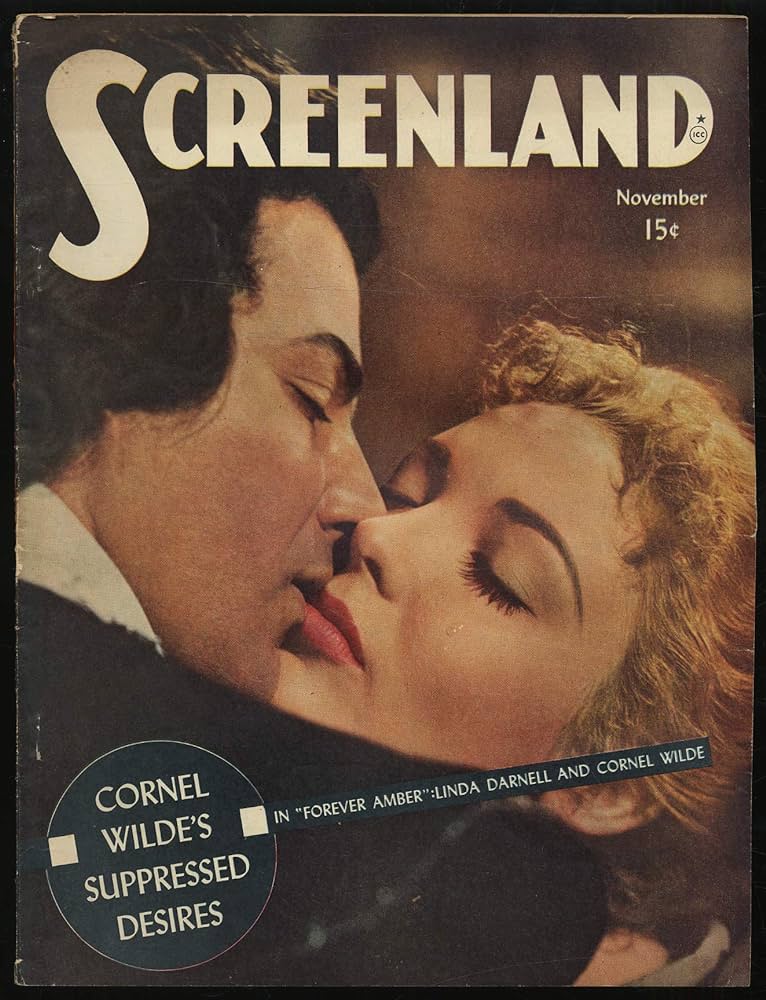

But it was as Chopin opposite Merle Oberon as George Sand that Wilde broke out of the pack. “When ‘A Song to Remember’ came along (1944), I begged for a test,” he told Hopper. “The powers that be wouldn’t consider it. ‘You’re too healthy’ (to play a tubercular musician).” Finally after three months of testing what Wilde described as “every other actor” in town, he was given the role and received an Oscar nomination. (One critic later said he grew paler and wanner with each reel while fingering an impressive sound track on a mute piano. The pianist off screen was Jose Iturbi.) But the success proved a Pyrrhic victory, for afterward producers came to consider him fit only for costume dramas.

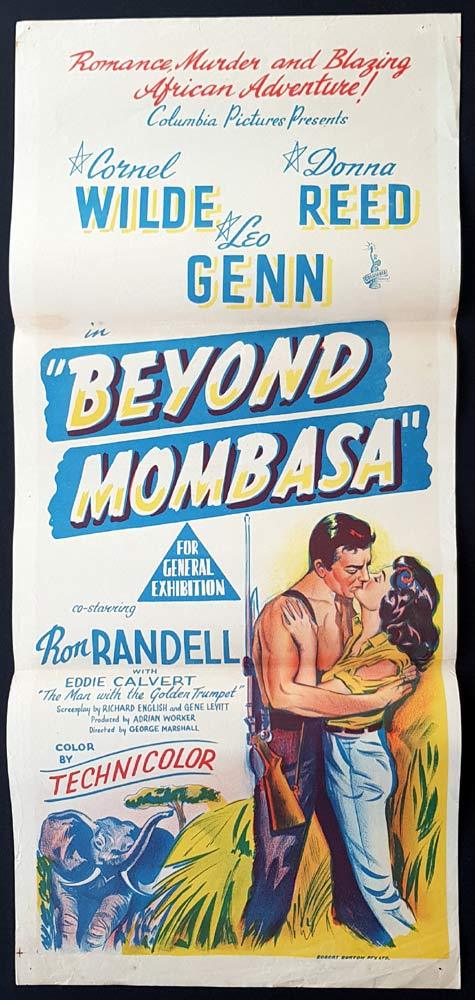

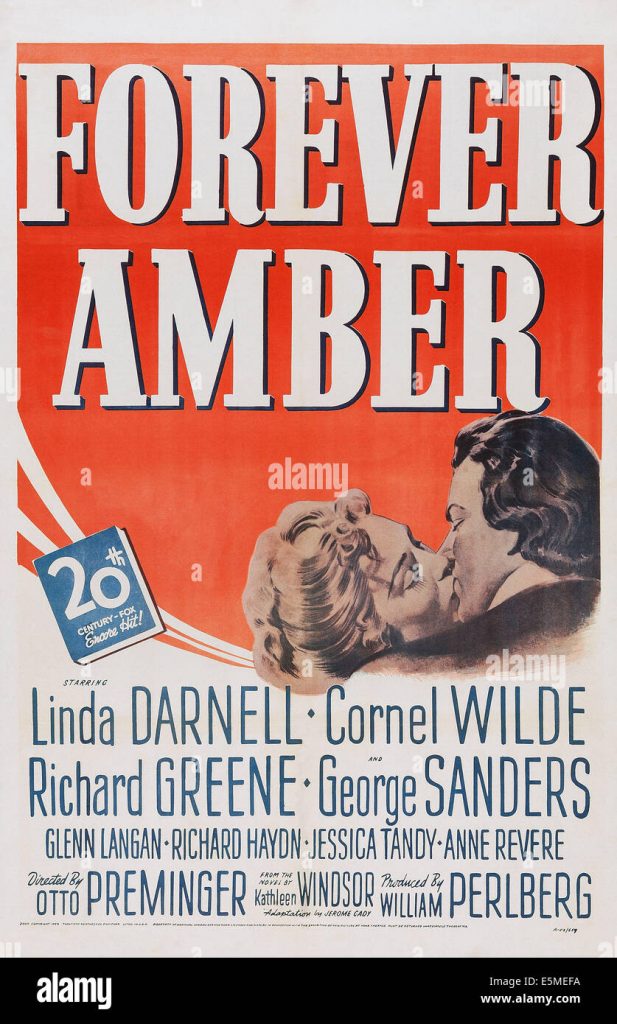

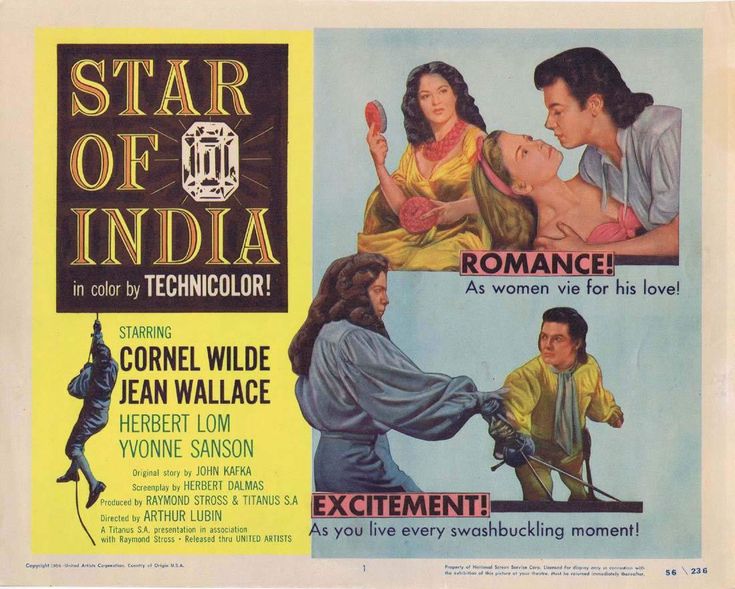

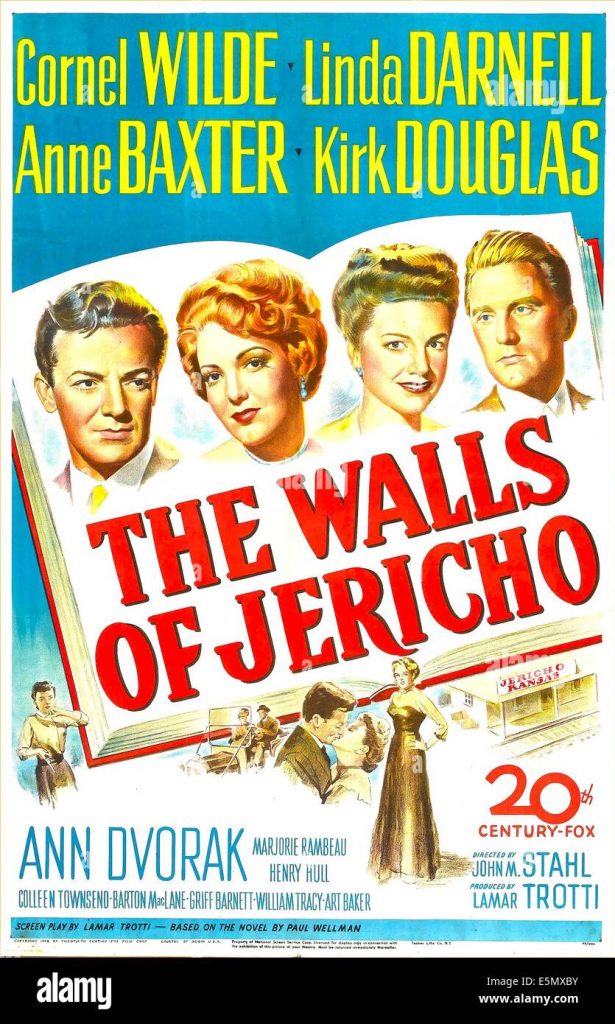

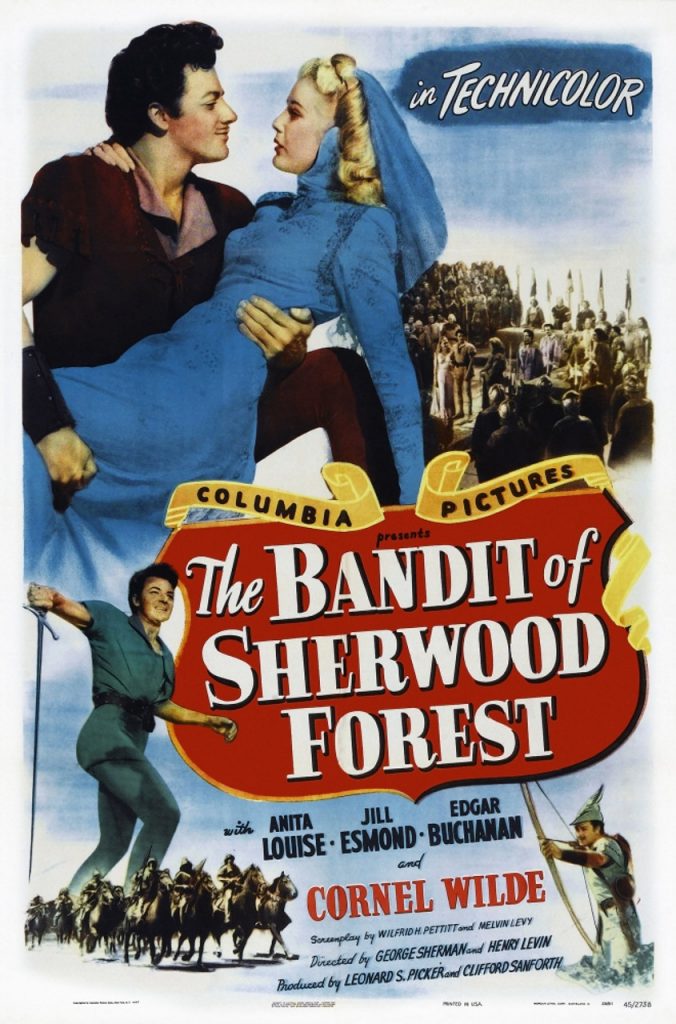

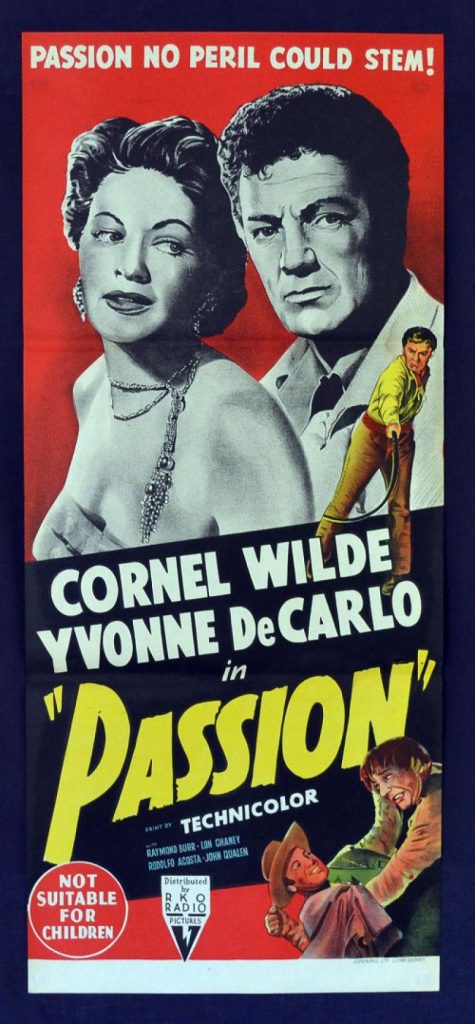

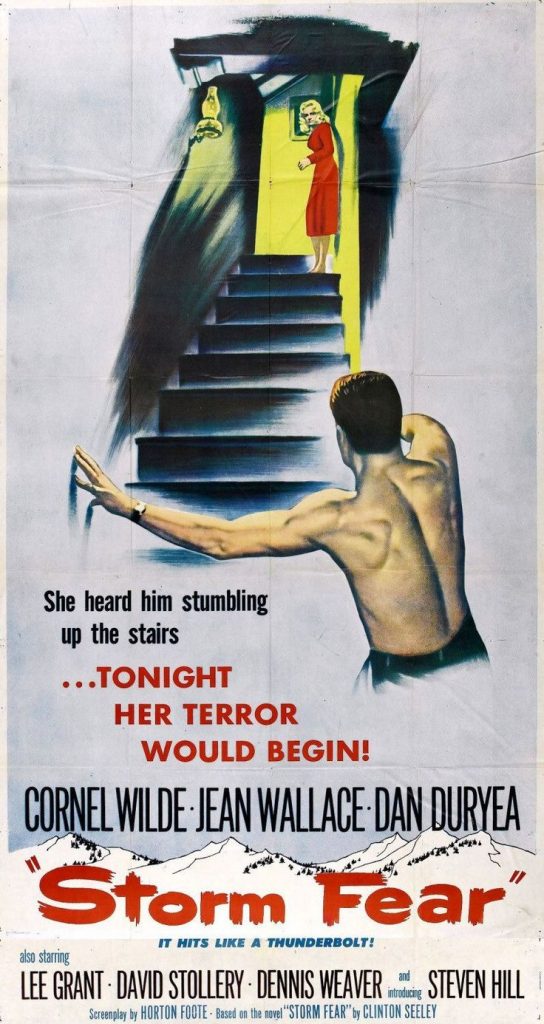

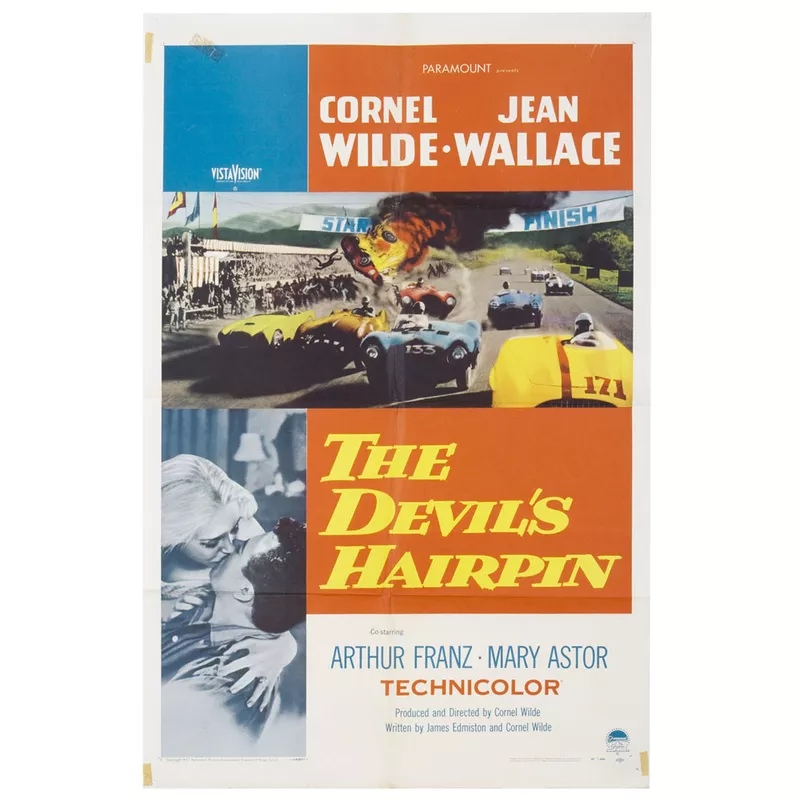

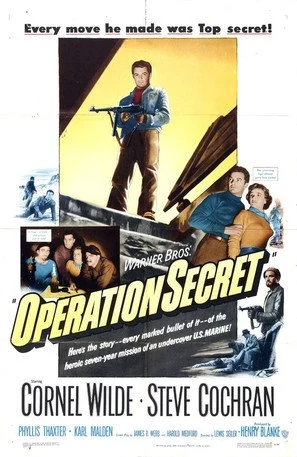

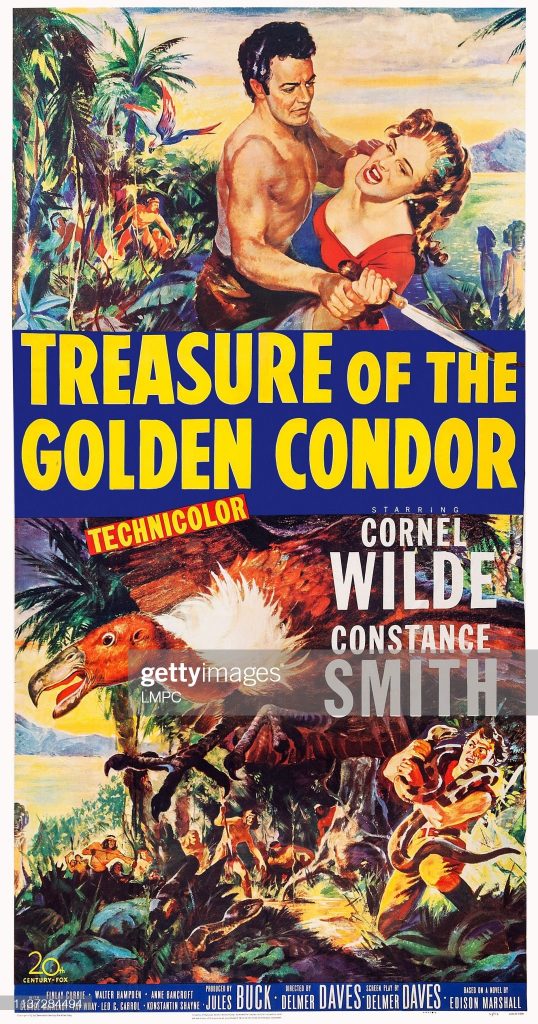

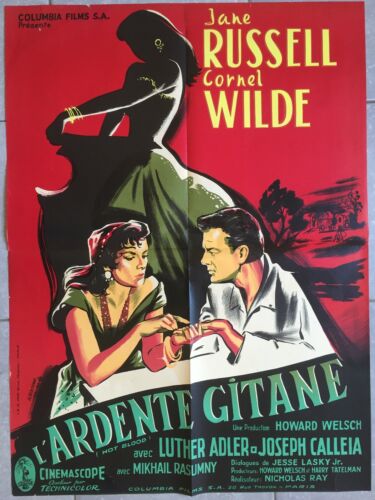

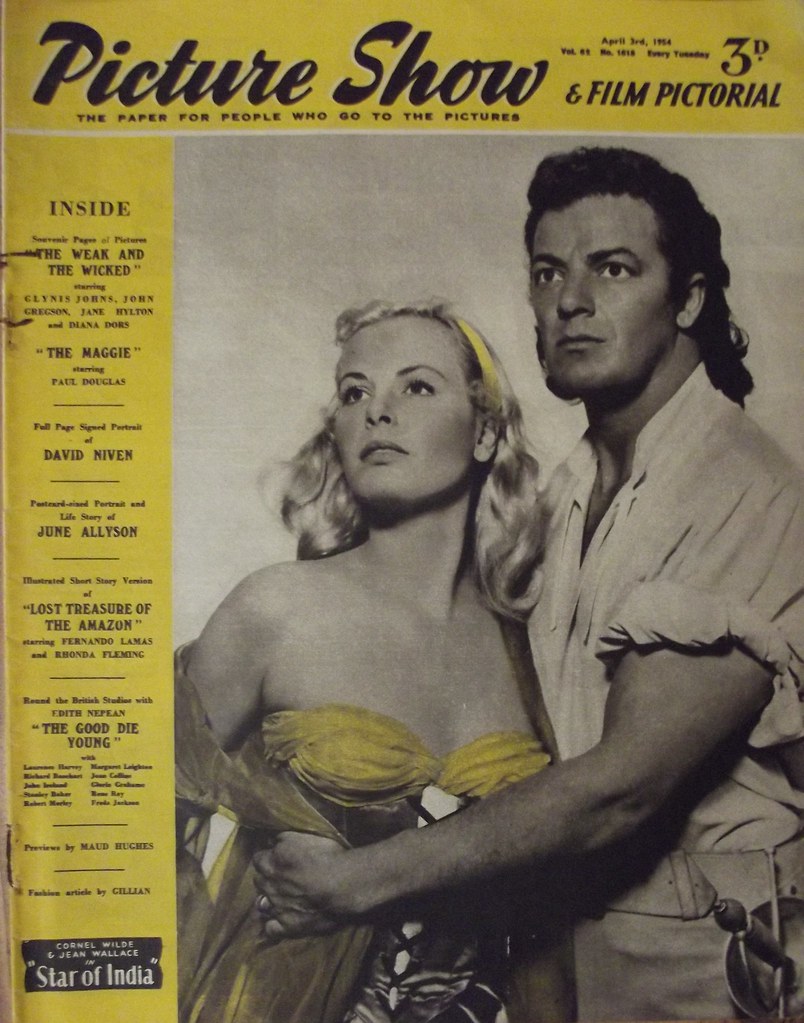

He stayed in costume for “The Bandit of Sherwood Forest” and “Forever Amber,” appeared in such melodramas as “Roadhouse,” and “The Walls of Jericho” and then made the Big Top classic “The Greatest Show on Earth” for Cecil B. Demille in 1952. But the roles had taken on what seemed to Wilde to be a certain unsettling sameness, and he abandoned what was at the time a $150,000-a-picture career to become a writer-producer-director. He formed, with his second wife actress Jean Wallace (they had performed together in “Star of India”), Theodora Productions, and in they 1955 produced “Storm Fear.” The other pictures he starred in, produced or directed included “The Big Combo,” “The Devil’s Hairpin,” “Maracaibo,” “Sword of Lancelot,” “Beach Red” and “The Naked Prey,” in which he spent most of the 94-minute film wearing a loincloth and brandishing a spear as savages pursued him as they would a lion.

Despite the plot’s naivete, it was nominated for an Oscar for its script.

The “Los Angeles” obituary can also be accessed online here.