Laurence Oliver. TCM Overview.

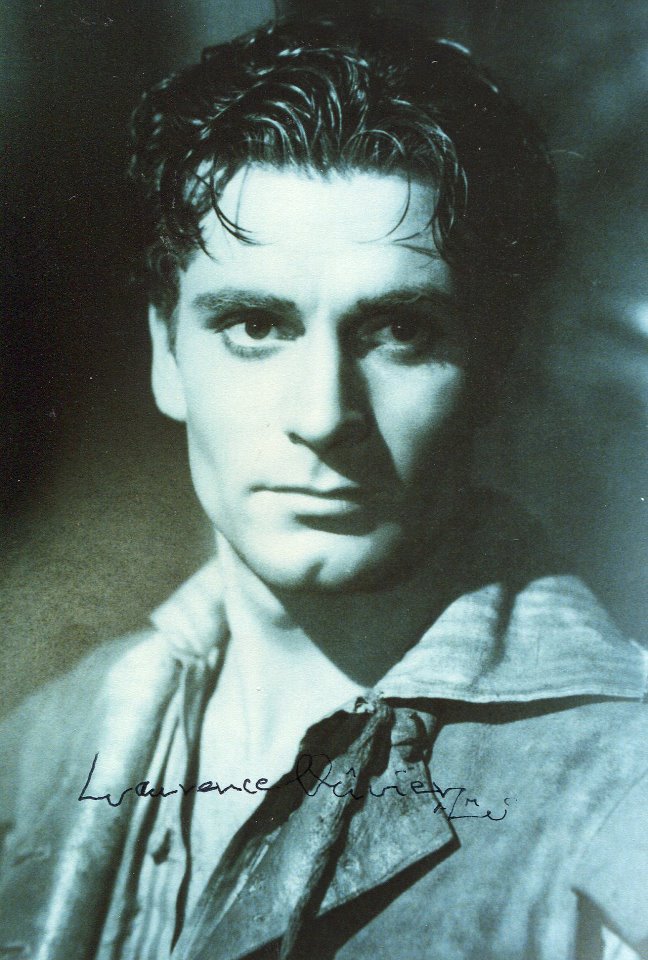

Laurence Oliver was born in 1907 in Dorking, Surrey. He acted with the Old Vic and made his film debut in 1930 with “Too Many Crooks”. In 1931 he spent a brief time in Hollywood where he made “Westward Passage” among others. By 1933 he was back pursuing his career in Britain. He venture back to Hollywood in 1938 to make “Wuthering Heights”, “Rebecca”, “Lady Hamilton and “Pride and Prejudice”. During World War Two he returned to Britain to enlist. His career soared to new heights with his “Hamlet” and he had a very prolific career on stage and screen both in Britain and the U.S. until shortly before his death in 1989.

TCM Overview:

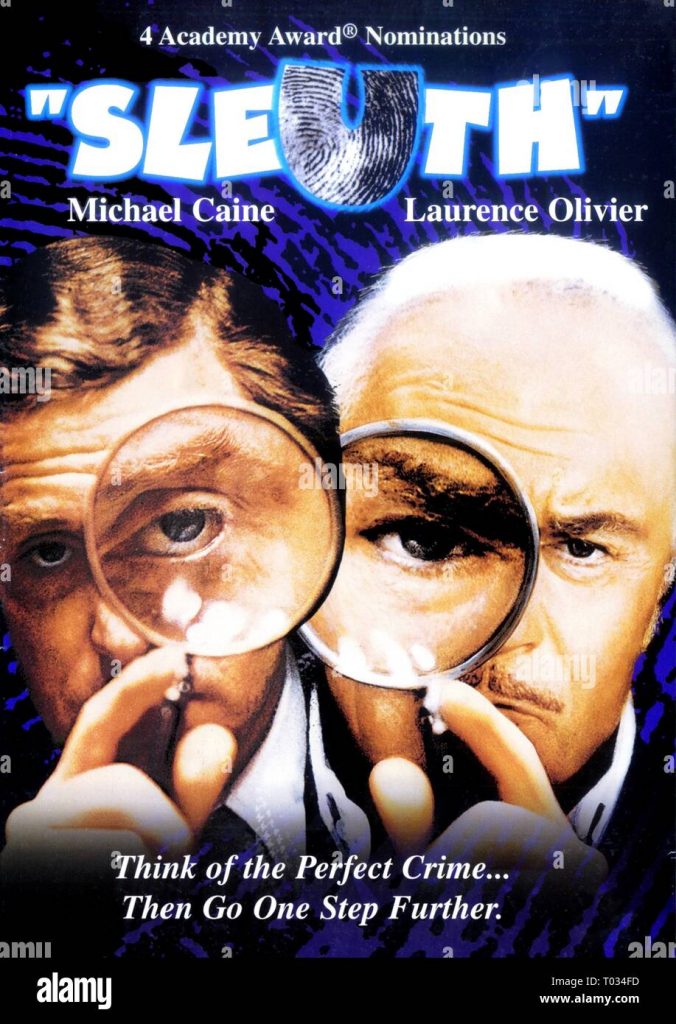

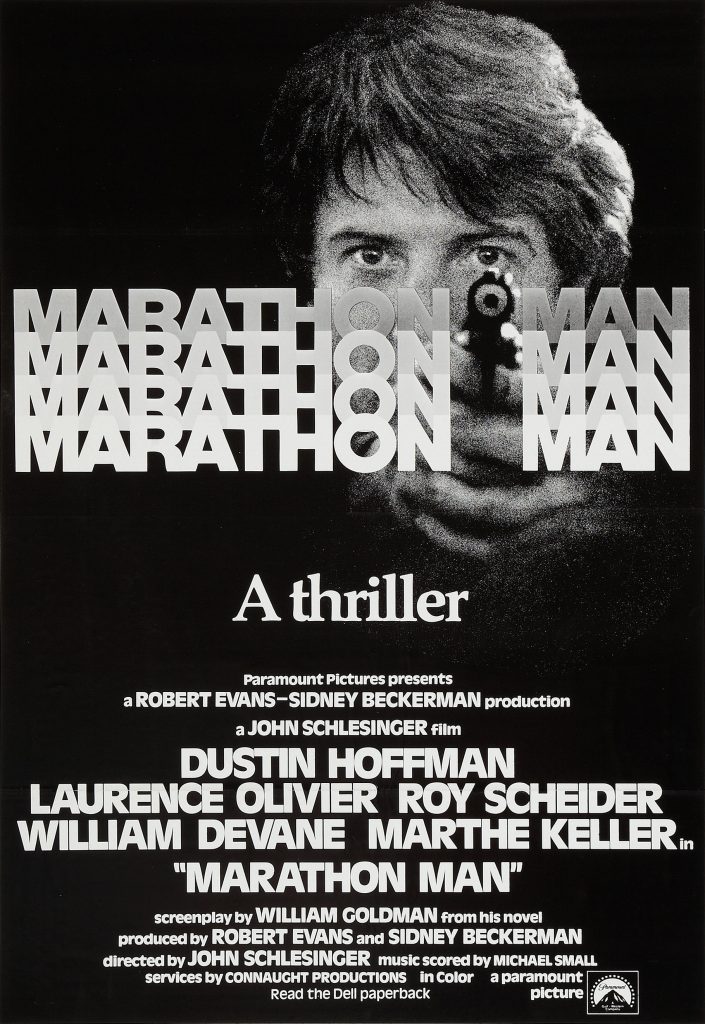

He was by wide consensus the greatest actor of the 20th century. In an age when the “legitimate” theater held firm to primacy over motion pictures, and classical theater over modern, Laurence Olivier crossed seamlessly between both, even bridging the gap between popular culture and the Shakespearean and classic drama canon of which he was master. His official, glamorized coupling with multiple Oscar-winner Vivien Leigh – “the King and Queen of the theater,” as contemporary Sir John Gielgud once dubbed them – proved far darker than the fairy tale advertised to the public, even as countless rumors swirled around his eclectic extracurricular relationships. His legacy as the definitive Heathcliff and Hamlet, his acclaim even a generation later as the vengeful cuckold in “Sleuth” (1972) and a ruthless Nazi doctor in “Marathon Man” (1976), would see him earn 14 Oscar nominations, three statues, five Emmys out of nine nominations, two British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) awards out of 10 nominations – only a few indicators of his titanic impact on his craft and indeed on Western culture.

He was born Laurence Kerr Olivier on May 22, 1907 in Dorking, Surrey, England, the third child of Agnes and Rev. Gerard Olivier – she a warm and doting woman, he an austere and stolid High Anglican minister. Gerard soon moved the family to the bleaker urban scape of London to minister its Dickensian slums, though his considerable inheritance afforded “Larry” a series of parochial schools, including All Saints Church’s “choir school,” which began refining his penchant for the arts, and saw him play Brutus in “Julius Caesar” at age 10. He would be devastated two years later when his mother died of a brain tumor. In 1922, the school company staged its version of “The Taming of the Shrew” at a Stratford-on-Avon Shakespeare birthday festival, with Olivier drawing mainstream raves for his shrewish Katharina (in true Shakespearean drag). He next attended St. Edward’s in Oxford, continued to display thespian talent and, upon graduation, his father advised he pursue a theatrical career.

At 17, he won a scholarship to the Central School of Speech and Drama, but soon began a two-year stint with the Birmingham Repertory Company. There, he met fellow thespians Peggy Ashcroft, Ralph Richardson and Jill Esmond, with whom he became enamored. They would all graduate to London’s West End theater district. Soon Olivier became a hot commodity, as evidenced by his lead in a garish, overambitious stage production of the French Foreign Legion adventure “Beau Geste.” In 1929, he crossed the Atlantic to make his Broadway debut in “Murder on the Second Floor,” reuniting with Esmond, who, upon his arrival, immediately agreed to his marriage proposal. They would marry in 1930. Also that year, Olivier scored a role in a new play, “Private Lives,” by playwright Noel Coward, who, by various accounts, either successfully or unsuccessfully proffered a sexual dalliance with Olivier, at any rate inaugurating a lifelong friendship. Esmond joined the play’s cast for an early 1931 Broadway run, which caught the attention of American film studios.

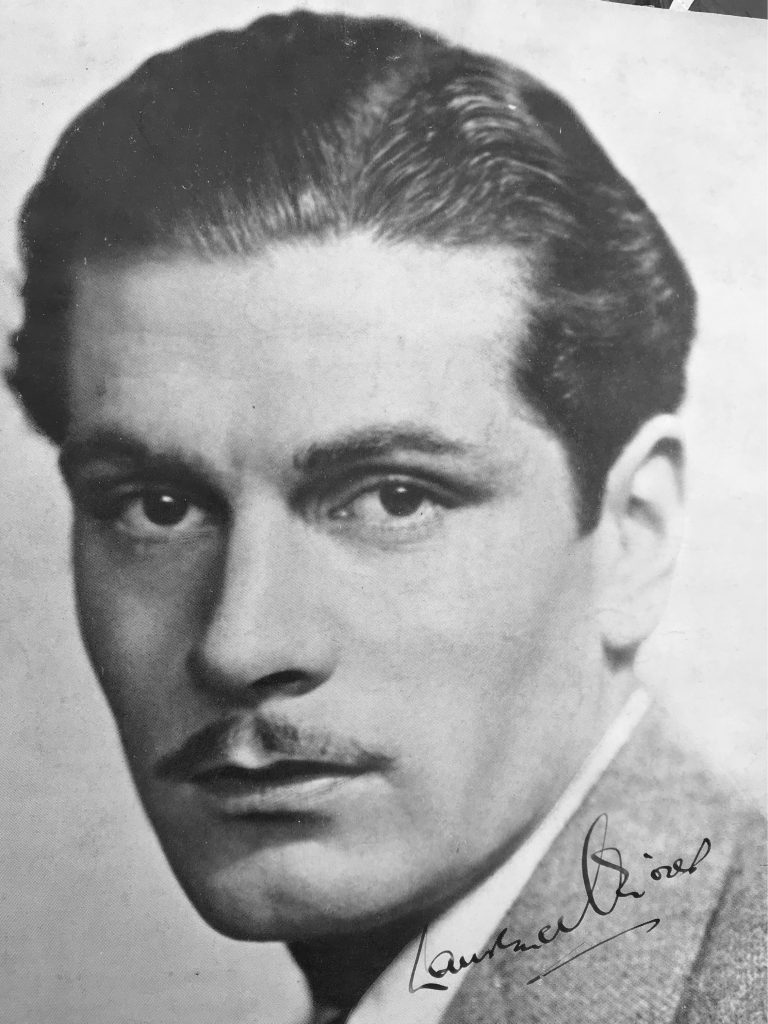

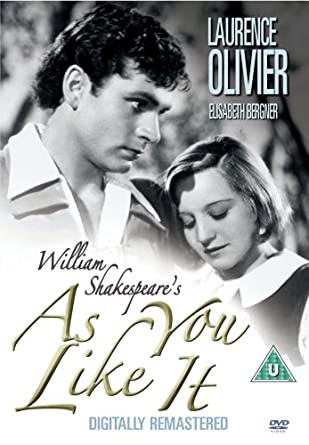

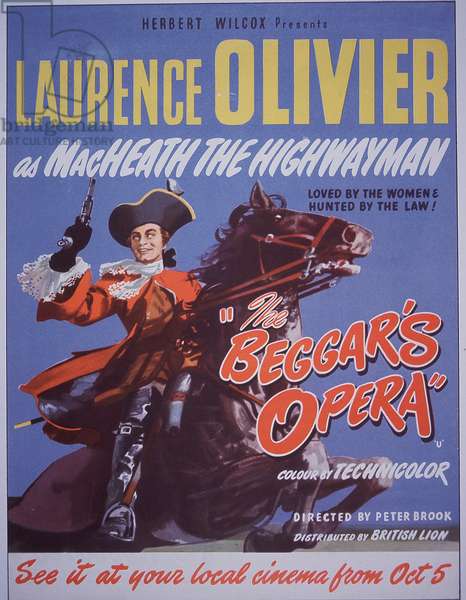

They lured the couple to Los Angeles, but Olivier’s three initial movies for RKO – he liked only “Westward Passage” (1932) – did little to set the box office afire. The couple returned to the U.K., where they made their only movie together, “No Funny Business” (1933). MGM would lure him back to Los Angeles, with a one-off project opposite Greta Garbo, but the studio’s grand dame intimidated and took an instant dislike to the newcomer so MGM fired him. Humiliated, Olivier returned to London and the stage with a string of hits, becoming a producer for the first time with the play “Golden Arrow,” co-starring his young Irish discovery Greer Garson, and in a 1935 staging of “Romeo and Juliet” with Gielgud that would run an unheard-of six months. Olivier and Gielgud would take on the unique task of alternating on the Romeo and Mercutio parts. Olivier wowed critics, eschewing the formal, lyrical approach to the Bard by playing Romeo with naturalistic, hormonal verve, which may have spilled over to a physical relationship with his Juliet, Peggy Ashcroft. But at this same time, he became a singular attraction to a young actress who had made it to the West End herself under the name Vivien Leigh.

Leigh, already married and a mother, famously pronounced she would one day marry Olivier, and Olivier himself later claimed that after seeing her breakthrough play “Mask of Virtue,” he experienced “an attraction of the most perturbing nature I have ever encountered.” They starred together in film producer Alexander Korda’s “Fire Over England” (1936), with Olivier playing an agent of Queen Elizabeth on a mission to Spain and Leigh portraying one of the queen’s ladies-in-waiting and his lover, which, as their fervent on-screen embraces betrayed, they had become in real life. Leigh aspired to Olivier’s mastery of classic theater. As the relationship intensified, she eventually picked up his famous fluency in unfettered blue language. Olivier’s persistent religious guilt complicated things, as did Esmond’s recent pregnancy, soon to bear a son, Tarquin – though she remained publicly amicable with both of them. In 1937, Olivier joined the venerable Old Vic theater as a featured star, beginning the year in its production of “Hamlet,” even as he managed to arrange the first tandem projects for himself and his lover: a staging of “Hamlet at Denmark’s Elsinore Castle in the summer, and a film, “Twenty-One Days” (1940), with the two playing lovers on the lam after he accidentally kills her estranged husband. Neither liked the latter, shelving it for three years, but at the end of the production, as news spread of Hollywood’s adaptation of the blockbuster novel Gone With the Wind, she famously prophesied she would play its protagonist, Scarlett O’Hara. Leigh and Olivier soon fessed up to and separated from their respective partners and, after his rare comedic turn with Merle Oberon and Ralph Richardson in “The Divorce of Lady X” (1938), he and Leigh headed to Hollywood – she to fulfill her prophecy and he to finally break through the film barrier as a romantic heartthrob.

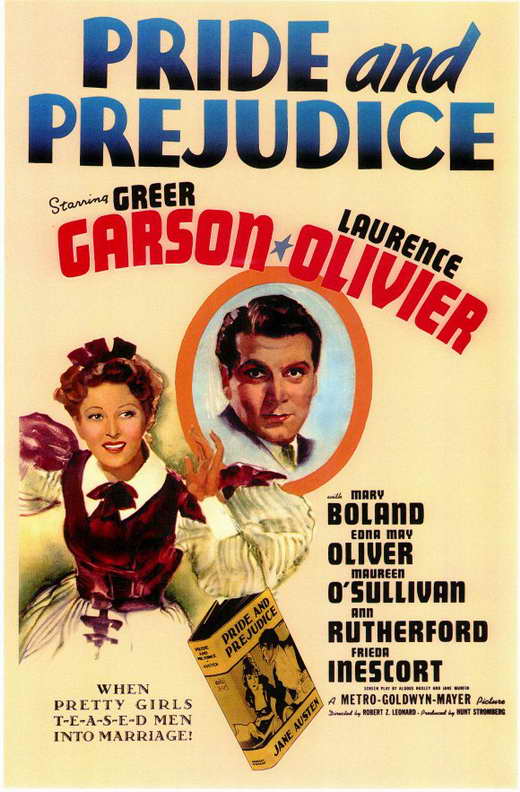

It would be Emily Bronte’s “Wuthering Heights” (1939), adapted for film by indie producer Samuel Goldwyn and director William Wyler, that made Olivier a household name across the Atlantic. He played Heathcliff, one-time stable boy spurned for his low breeding by his first love, Cathy (Merle Oberon), who returns years later as a successful, brooding man with his heart hard and set on revenge against his lost love and anyone who had mistreated him in the past. He would credit director William Wyler with teaching him the toned-down nuances of screen versus stage acting, turning in his first Oscar-nominated performance. At the same time, Leigh won Best Actress as Scarlett O’Hara for her work in “Gone with the Wind.” In 1940, their respective spouses agreed to divorce and to the delight of fans, Leigh and Olivier wed. Olivier would rack up two more hits: “Pride and Prejudice,” reuniting him with protégée Greer Garson in the film adaptation of Jane Austen’s witty Victorian parlor romance; and Alfred Hitchcock’s “Rebecca,” which had him as a sullen aristocrat with a new wife (Joan Fontaine) driven to dredge up the mysterious fate of his first spouse while confined to his gothic mansion. Olivier’s disquieted, simmering performance drew yet another Oscar nomination.

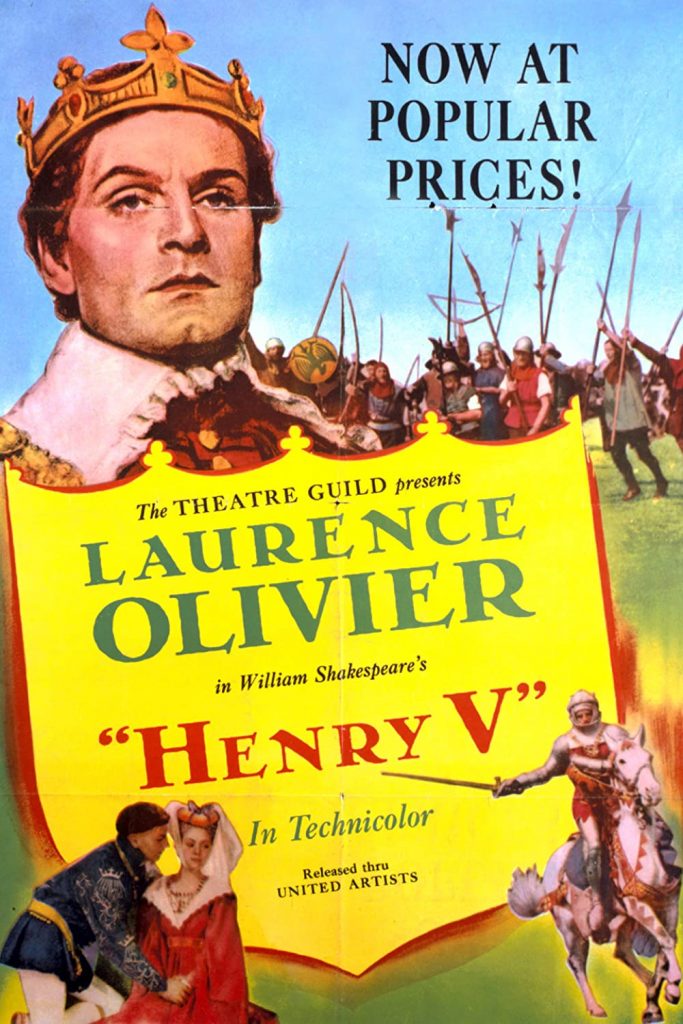

Olivier and Leigh returned to Britain to do another tandem picture for Korda, “That Hamilton Woman” (1941), which cast her as an unhappily married socialite and him as the British naval hero Horatio Nelson, which chronicled their illicit romance which became the great scandal of its time. Commissioned by the British government, he next mounted his most ambitious production, a Technicolor version of Shakespeare’s “Henry V” (1944). He produced, directed and starred in the critically acclaimed film, and his delivery of the famed St. Crispin’s Day speech became a rallying cry for the country’s ongoing war effort. The film’s 1946 U.S. release would earn him Oscar nominations for Best Actor and Best Picture, and though he won neither, his top-to-bottom helming of the project would earn him an honorary Academy Award in 1947. Also that year, King George VI knighted Olivier, making the couple “Sir Laurence and Lady Olivier.”

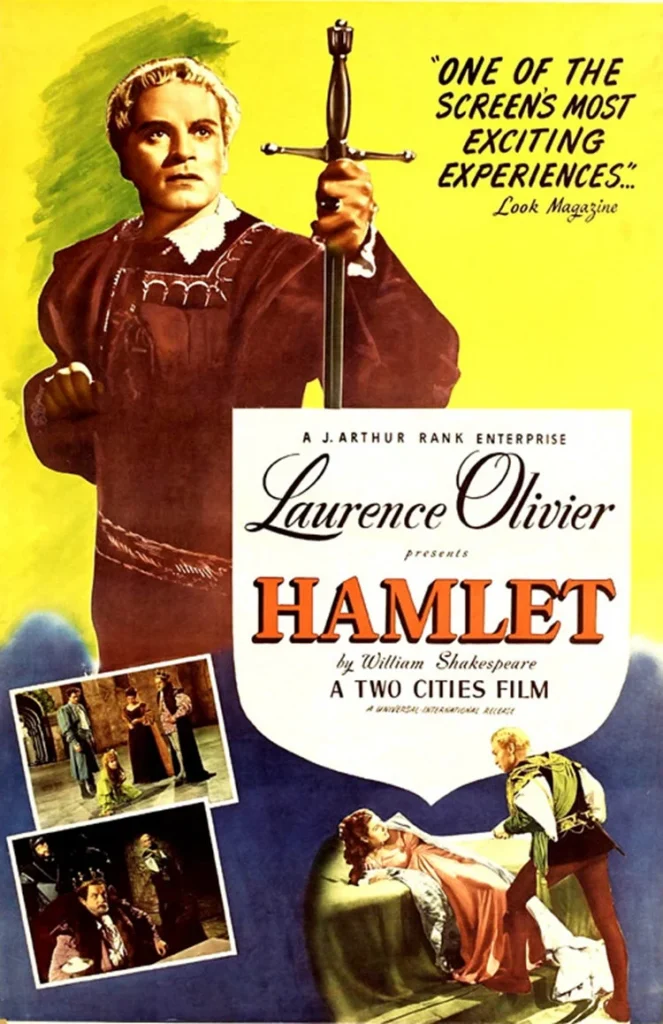

Despite the fairy tale mystique surrounding the legendary couple, all was not well in their household. Leigh increasingly suffered violent tantrums that she would not remember afterward, and to make matters worse, during production of “Caesar and Cleopatra” (1945) she suffered a miscarriage. Tuberculosis compounded her physical and mental health issues; she grew distant and jealous of Olivier’s successes and paranoid about his affairs, both imagined and real, at one point telling him matter-of-factly she was no longer in love with him. Seeking respite, Olivier strayed with any number of rumored partners even as he enabled her own long-term affair with actor Peter Finch, whom he hired for the Old Vic company after its 1948 tour of Australia. That year, he made history with his big-budget Shakespearean film adaptation of “Hamlet” (1948), in which he became the first director to direct himself to a Best Actor Oscar.

The Oliviers continued their stage collaborations; notably he directed her in the 1949 West End production of Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire.” He settled into a kind of caregiver role for his manic-depressive, bipolar wife, arranging a project of his own, the Wyler-helmed illicit-love tragedy “Carrie” (1952), to travel with her while she made “Streetcar” (1952) in Hollywood. Her co-star Marlon Brando later wrote he eschewed a tryst with Leigh out of respect for Olivier, but oddly, David Niven claimed in his autobiography that he witnessed Brando kissing Olivierat the couple’s mansion. (Though long a subject of rumor and controversy, Olivier’s third wife, Joan Plowright, would acknowledge his libertinism and bisexuality in a 2006 radio interview). Leigh was back with Finch in Ceylon in 1953 for the film “Elephant Walk” (1952) when she suffered a full-blown break, causing her to be hospitalized and be given a lifelong regimen of electroshock therapy, which would render her even more alien to Olivier.

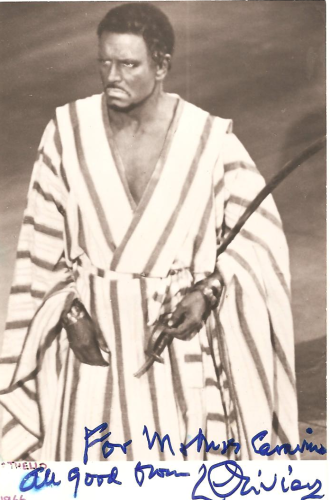

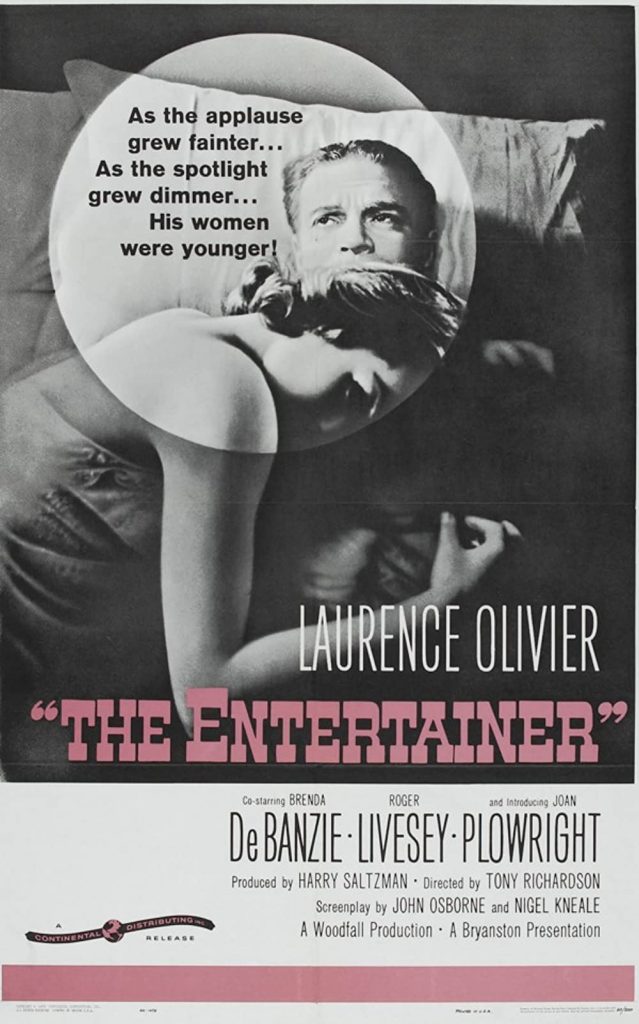

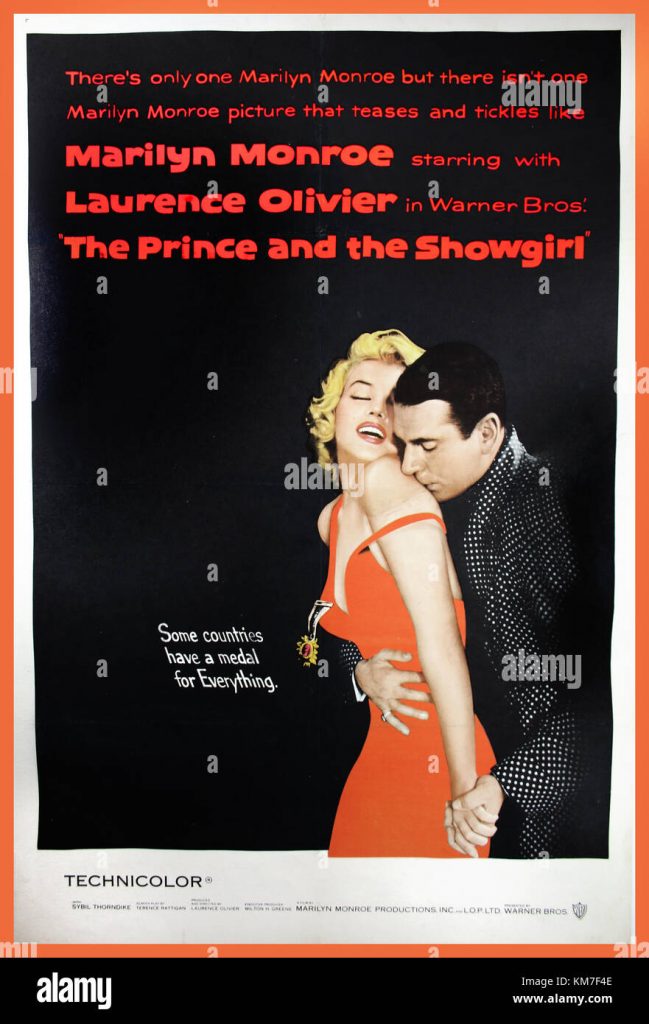

He earned another Oscar nomination for his villainous “Richard III” (1955), and followed it up with a Marilyn Monroe mismatched-pair fantasy, “The Prince and the Showgirl” (1957), which he also directed. Meanwhile, he had commissioned West End enfant terrible John Osborne to write him a drama that could contemporize his own image. Osborne produced “The Entertainer,” which had Olivier as an unpleasant, archaic song-and-dance man still working Britain’s crumbling dance-halls, metaphorical of an Imperial society in decay. He began a relationship with his onstage daughter, Joan Plowright. She would star with him in the 1960 film adaptation, which would earn Olivier yet another Best Actor Oscar nomination. He and Leigh would divorce that year, leading to Olivier and Plowright marrying in 1961. With the dissolution of the Old Vic company in 1962, he would soon oversee another regeneration called the National Theatre Company, with Olivier serving as its first director. Under his tenure, it would nurture a new generation of talent, including Michael Gambon, Derek Jacobi, Alan Bates and Anthony Hopkins. The National’s production of “Othello” would become the 1965 film, for which Olivier and his three co-stars would all win Oscar nominations.

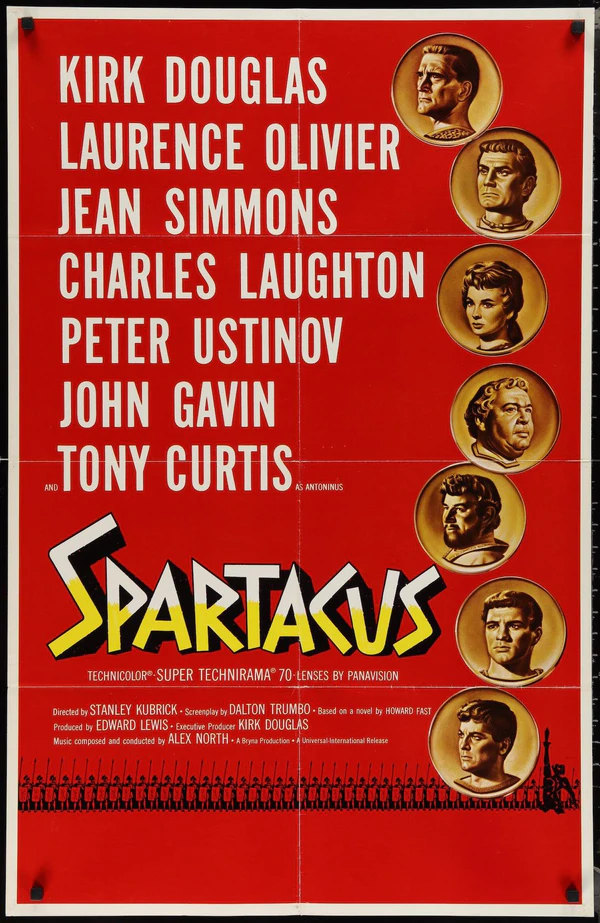

Olivier continued to be selective with film in the 1960s. His leading roles became less frequent but affecting, as with “Term of Trial” (1962), in which he gave a heartbreaking performance as a high school teacher whose life is turned upside down when a spurned student accuses him of seducing her; and his understatedly cool detective in “Bunny Lake is Missing” (1965). Olivier had also begun taking film-stealing supporting roles, in which he often played villains. He played Johnny Burgoyne, the dashing nemesis of the colonials Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster in George Bernard Shaw’s Revolutionary War drama “The Devil’s Disciple,” (1959); thwarted Douglas again as the scheming, draconian general Crassus in Stanley Kubrick’s epic “Spartacus” (1960); an Islamic would-be messiah in “Khartoum” (1966); a Soviet premier in “Shoes of the Fisherman” (1968); and, later, as the nefarious Dr. Moriarty in the revisionist Sherlock Holmes adventure “The Seven-Per-Cent Solution” (1976).

The late 1960s would begin a series of health crises for Olivier, starting with treatment of prostate cancer, but he would nevertheless be prolific in bringing the stage to mass media in the 1970s. He oversaw the translation of the National’s productions of Chekhov’s “Three Sisters” (co-starring Plowright) into a theatrical film and Eugene O’Neill’s “Long Day’s Journey Into Night” (1973) into a TV-movie for broadcast on ITV in the U.K. and ABC in the U.S, earning him an Emmy. However, he relinquished helm of the theater soon thereafter amid some contention with its board, just a few years before the company moved into the new Olivier Theater. In 1974, he barely survived the onset of the muscle disease dermatopolymyositis, but returned the next year with the TV-movie “Love Among the Ruins” (ABC, 1975), playing a barrister charged with defending a woman he fell in love with years ago, both now in their twilight years. Both he and Katherine Hepburn won Best Actor Emmys for a “special” broadcast. He would also bring Tennessee Williams’ “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” and William Inge’s “Come Back, Little Sheba” to NBC in 1976 and 1977, respectively.

His selective, age-adjusted cinematic outings brought continued accolades, notably three more Oscar nominations for his manipulative cuckolded husband in the cat-and-mouse thriller “Sleuth;” ice-blooded Nazi dentist, famously torturing Dustin Hoffman via check-up in “Marathon Man” (1976); and as a dry, unflappable Nazi hunter in “The Boys from Brazil” (1978). He received a second honorary Oscar the following year for his body of work. He also stood out as an old pickpocket shepherding the two smitten adolescents in Venice in “A Little Romance” (1979) and as the vampire hunter Van Helsing in the 1979 remake of “Dracula.” His work as Neil Diamond’s orthodox Jewish father in the remake of “The Jazz Singer” (1980), however, was viewed as overwrought and mawkish. He won another BAFTA Best Actor nomination for “A Voyage Round My Father” (1983) opposite Alan Bates, and won yet another Emmy that year for his turn as “King Lear” (ABC). Worried about his estate, he peppered his later years’ work with glorified cameos – some in projects he knew to be awful, as with “Inchon” (1981) and “Clash of the Titans” (1981), but others in higher-quality fare like “The Bounty” (1985). In 1984, the top awards for British theatrical awards were renamed the Laurence Olivier Awards. His infirmities became evident during the March 1985 Academy Awards telecast, when he capped the evening presenting the Best Picture Oscar, but inadvertently sidestepped the tradition of running down the nominees first and simply stated the winner, “Amadeus.” He appeared in the “Entertainer”-reminiscent Granada TV series “Lost Empires” (PBS, 1987) about the decline of U.K. vaudeville, for which he earned his last Emmy nomination, then made a final cameo as an old soldier in Derek Jarman’s stylistic “War Requiem” (1989). He died on July 11, 1989, at his home in Steyning, West Sussex. His burial at Westminster would rival British state funerals, televised nationally throughout the U.K.

By Matthew Grimm