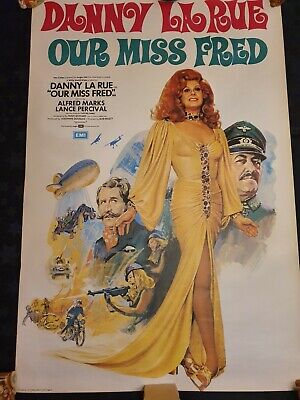

Danny La Rue was born Daniel Carroll in Cork in 1927. When he was six, his family moved to London. He served in the British Royal Navy as a young man. He began performing in nightclubs in the late 1950’s and soon had built up a following for his a female impersonations. He was very popular in the 1960’s and had his own nightclub. In 1972 he starred in his only film “Our Miss Fred”. Danny La Rue died in 2009 at the age of 81.

His “Guardian” obituary:

Danny La Rue, who has died aged 81, flouted the usual showbusiness rule that, to be funny, every female impersonator needed to have an obvious suggestion of –hobnailed boots beneath a long frock. In a variation on this tradition, he appeared attired in sequinned dresses, but immediately said “wotcher, mates!” in a gruff voice. Yet what La Rue achieved was to replace a traditionally derisive mocking of women, that showed them as faintly grotesque, with glitter and elegance. He did it to such an extent that, apart from his height of over 6ft, he might easily have been a beautiful woman trying her luck with saucy jokes and sentimental songs. He became the first performer for many years to base his entire career on impersonating women.

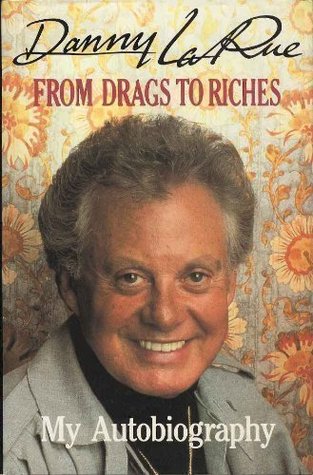

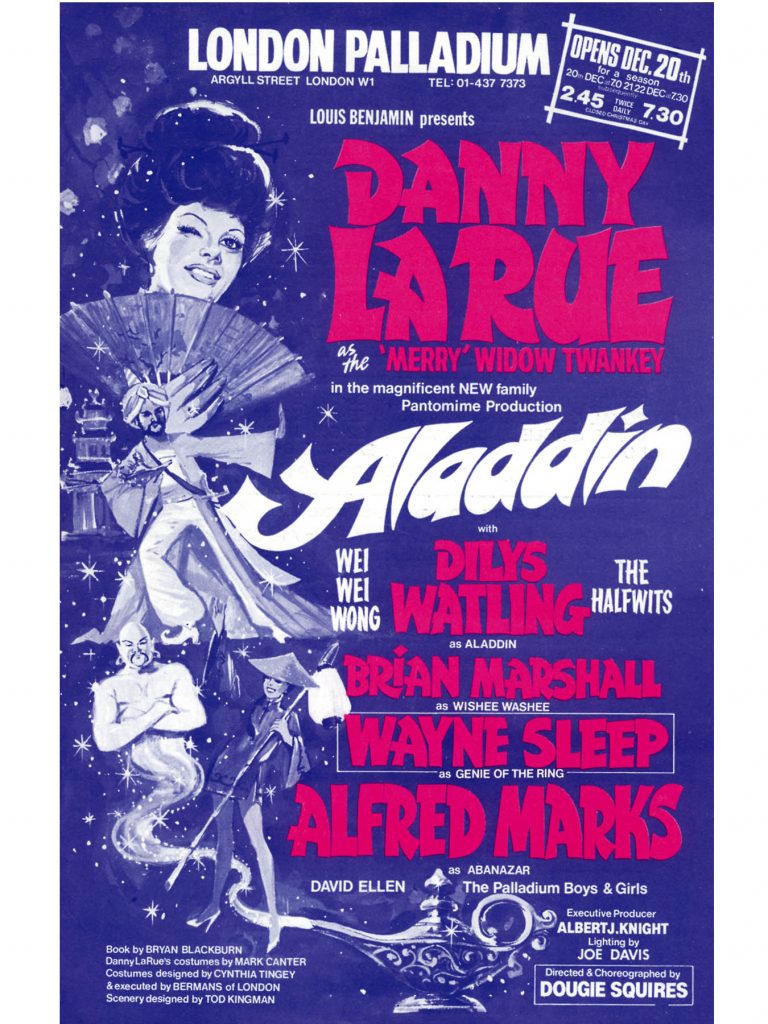

“Vulgar, yes, but there is nothing crude about me,” was his guiding maxim, as he flounced around variety stages, clubs, pierheads and pantomimes, doing a dozen changes a show, sometimes with stylish but over-the-top dresses which cost £5,000 each. At his peak, in the 1970s, he was earning the equivalent of £2m a year, and had four homes, a Rolls-Royce and an entourage of 60. La Rue was never a gay icon, nor a butt of the feminist movement, which sometimes surprised him. His core audience was, in fact, blue-rinsed ladies of a certain age who sent gushing letters congratulating him on his awards: showbusiness personality of the year in 1969, theatre personality of the year in 1970, 25 years in show business award in 1976 and entertainer of the decade in 1979. They wrote saying how much they admired his legs or his self-manufactured rubber bosom, presumably because they identified with him and were comfortable with his act – though it sometimes included raucous jokes which, coming from anyone else, might have caused deep offence. He got away with it, he claimed, because everyone knew that everything he did and said was just a pretence: he regarded himself as an actor.

Although Paul Scofield tried to –persuade him to act in “legitimate” –theatre, and Laurence Olivier wanted him to play Lady Macbeth, La Rue did not risk trying to escape his limitations. He would explain that taking off –Marlene Dietrich, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Bette Davis and Joan Collins, or Sophie Tucker singing My Yiddisher Mama, was acting enough. As a cabaret perfomer, he could be decidedly risqué, earning himself the nicknames Danny La Rude and Danny La Blue. Offstage, he could also be reckless and get away with it. Once, he was appearing at a London club and in a –Coventry pantomime simultaneously. At the same time, the royal family were asking for an increase in the civil list. When the Duke of Edinburgh, visiting La Rue’s show, asked him if he was doing it for the cash, La Rue replied that it seemed to be all the fashion. A Guardian critic said in the 1960s that La Rue’s material was “dirty night-club jokes for drunks and bored people and other actors, and yet it is truly cleansing and cathartic”. To which a reader from Hampstead – not usually regarded as the centre of La Rue’s core audience – inquired acidly whether the critic was “going through a period of severe mental strain”. The reader –obviously regarded La Rue’s material as neither filthy nor psychologically significant, just funny. This was the received opinion throughout a long career which, he said, was sustained by discipline and application.

Born Daniel Patrick Carroll in Cork, Ireland, La Rue was the youngest son of a Roman Catholic cabinet-maker, who had five children. La Rue never knew him. His father went to New York in the 1920s with the idea of bringing his family over later, but died before this could happen. Danny was then 18 months old. His mother, whom he described as his life’s inspiration, decided to compromise by seeking the family’s fortunes in England. She lived in Soho, central London, struggling on her widow’s pension and wages as a seamstress to provide for the large family, while young Danny attended schools in London and then, evacuated from London during the blitz, in Exeter. One day he found his mother in tears because she didn’t know where the money for his new school uniform was going to come from. On leaving school, he earned £1.50 a week in a –bakery; wartime rationing was in place and he was allowed to take cakes home as a perk. He got a job in Exeter as a window-dresser, then moved back to London, doing the same job for an Oxford Street store.

Called up for the Royal Navy, he made his first stage appearance, aged 18, as a native girl in a comic send-up of the serious play White Cargo. John Gielgud saw it in Singapore and told La Rue that he should take his ability to make people laugh more seriously. Once he left the navy, he did so. An old naval friend told him about auditions for an all-male chorus in the show Forces Showboat. Harry Secombe was in the same show.

Forces Showboat went on tour for months, but La Rue saw little point in dressing up as a woman in the –provinces. It didn’t seem to be getting him anywhere, so he returned to the Oxford Street store and initiated lunch-time fashion shows. Then the promoter Ted Gatty persuaded him to do a West End revue in drag. He would do it, said La Rue, as long as it were not under his real name. When he arrived for rehearsals he found that Gatty had already given him the name Danny La Rue. The producer Cecil Landau saw the show and got La Rue a two-week slot at Churchill’s club in Mayfair, which turned into a three-year engagement as top of the bill. La Rue spent the 1950s appearing on stage, often in –pantomimes staged by the impresario Tom Arnold. He also appeared in cabaret in clubs with such success that, in the early 1960s, he opened Danny’s, his own club in Hanover Square, which lasted nine years.

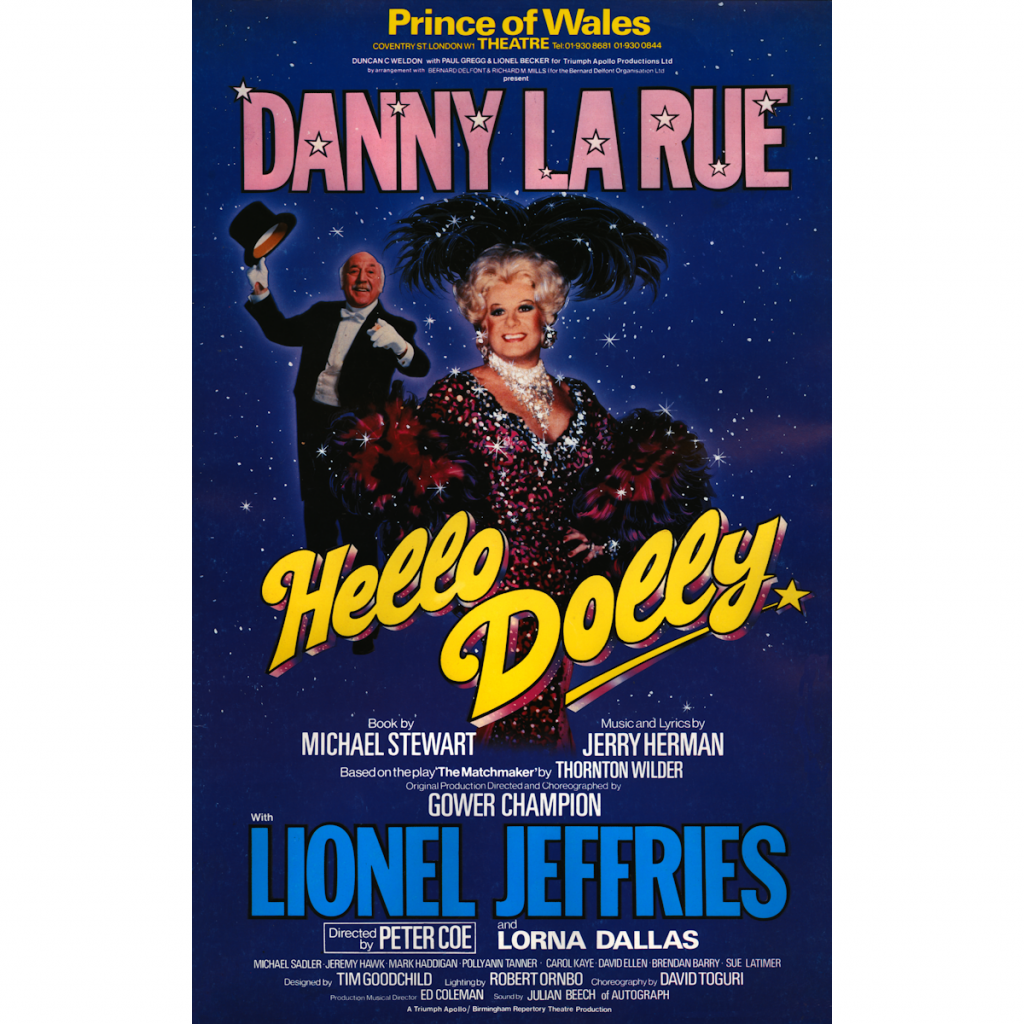

This was in contrast to a later business venture, in the 1970s: restoring the derelict stately home Walton Hall near Stratford-upon-Avon, which he had bought for £500,000 – much of his considerable savings. He poured the rest into restoration and turning it into a hotel and arts centre, only to find that the two Canadian managers were conmen who had left him with a pile of unpaid bills, for which La Rue was legally responsible. The day after his 56th birthday, La Rue’s company went into voluntary liquidation and he was forced to sell his home in Henley to pay off the debt. It got worse. In 1984 he took the lead in Hello, Dolly! which was critically panned and closed soon after. Later that year, his manager of 30 years, Jack Hanson, whom he described as “the love of my life”, died of a stroke. La Rue drank himself to sleep every night until a –psychic told him that his pet dog was the reincarnation of Hanson. Taking –further comfort from his Catholic religion – he kept a little shrine by his –bedside – La Rue resumed his disciplined routine of personal appearances at pierheads and in pantomime, rationing his television appearances as always. Why, he asked, should people pay to see him on stage when they could see him for free on TV?

He never married and was angry at those who called his announced, but later called-off, engagement to an American millionairess in 1987 a publicity stunt. In 2000, his companion Wayne King, an Australian pianist, died aged 46, of Aids. Two years later, in recognition of the thousands of pounds he raised for Aids charities, La Rue was appointed OBE (the Queen was said to be a great admirer of his act). Suffering from the eye condition macular degeneration, in 2006 he also suffered a stroke, though even then his agent said that La Rue was “dying to get his old frocks out, dust them off and get back in the limelight”. Shortly afterwards, in poor health and receiving financial assistance from an actors’ charity, he moved in to the home of his former dresser and longtime friend Annie Galbraith, who cared for him until his death.

• Danny La Rue (Daniel Patrick Carroll), female impersonator and actor, born 26 July 1927; died 31 May 2009

The above Dennis Barker obituary on Danny La Rue can also be accessed online here.