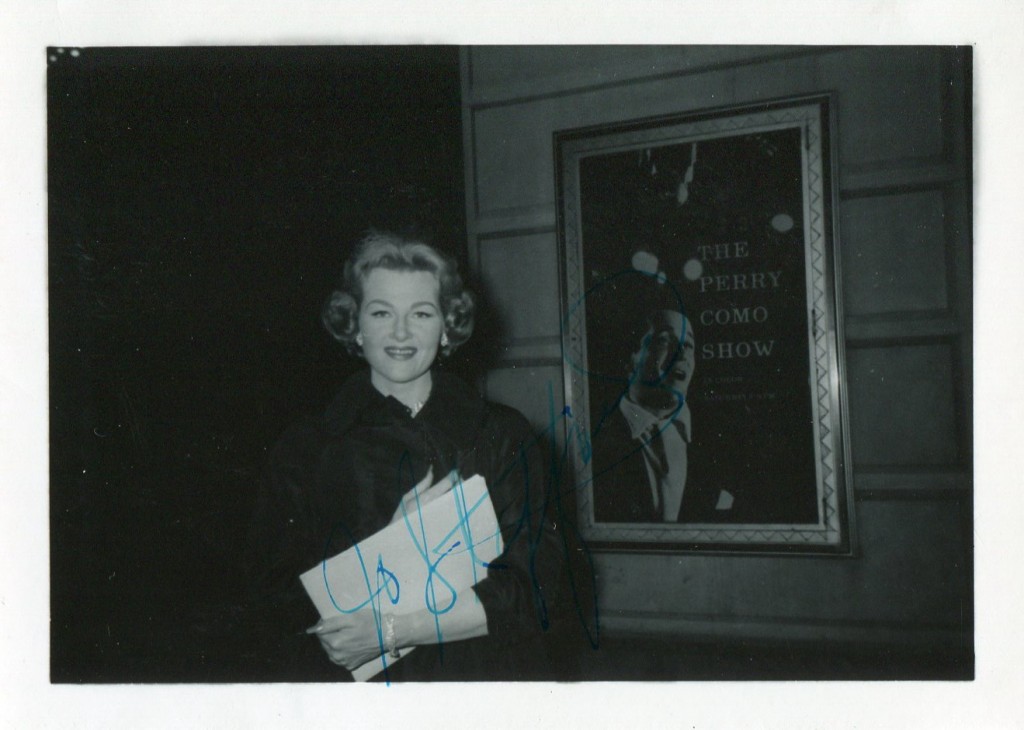

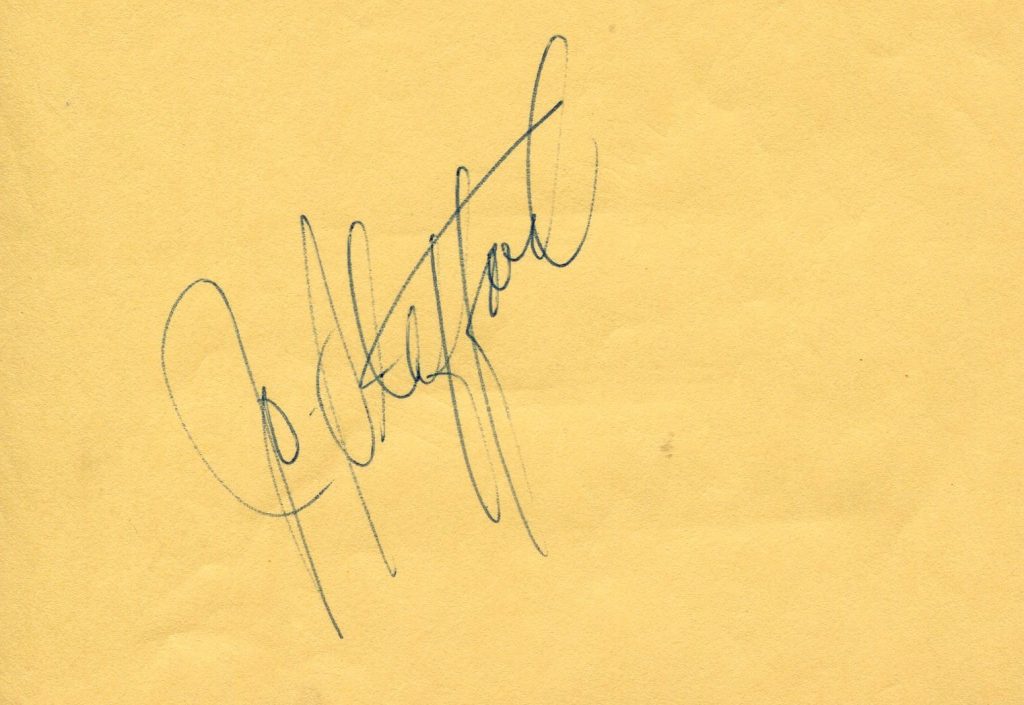

Jo Stafford was one of the most popular recording artists in the 1950’s. Her songs such as “You Belong to Me”, “Allentown Jail” and “Shrimp Boats” are still played to-day. She was born in 1917 in California’s San Joaquin Valley. She became the lead female singer with the legendary Tommy Dorsey Orchestra. She left the band in 1944 to go solo and had hit after hit.She was featured in the films “Biloxi Blues” in 1988 and “The Two Jakes” in 1990. Jo Stafford was married to the band leader Paul Weston. She died at the age of 90 in 2008.

Her “Guardian” obituary by Veronica Horwell:

The obituary below, of the singer Jo Stafford, incorrectly attributed a quote that she was “a highly educated folk singer working mostly in other idioms of American music” to Nancy Franklin of the New Yorker.

One female voice reigned over American music in the era between Frank Sinatra’s swooning bobbysoxers in the mid-1940s and Elvis Presley getting their little sisters all shook up in 1957. It was freighted with knowledge of trouble and loss but soared sure and clear; the voice of Jo Stafford, who has died aged 90. She was a diamond, gold and platinum disc seller of 25m records in every genre.

She was what she mocked, the third of four daughters of an Appalachian hill country couple, Anna York and Grover Cleveland Stafford. Jo was born at Lease 35, raw land near Coalinga, California, where the family had followed oilfield roughneck Grover in search of work.

They remained Tennessee in accent and music. Anna played five-string banjo. The older girls taught Jo to sing, and as her voice expanded to an octave and a half in a decade, Anna insisted she train as an operatic coloratura. She managed only five years, for lack of cash. The Stafford Sisters sang on radio and in movie musicals, then Jo went into a group, as the sole female – a short, hungry dumpling in horn-rimmed glasses – among seven male Pied Pipers.

Paul Weston, arranger for Tommy Dorsey’s band, heard their balanced voices with lead Stafford shaping the sound. In 1938 he recruited them for Dorsey’s radio show in New York, a gig that ended when the sponsor heard and hated their scat lyrics. But Dorsey summoned the octet, reduced to a quartet, on tour. “Most of the time you never even saw a bed,” she recalled. “You slept and dressed on the band bus.” After another thousand times around the block in the bus, she made a record, Little Man With a Candy Cigar (1941).

Weston gave her a break. He worked with Bing Crosby at Paramount Pictures, and met songwriter Johnny Mercer, co-founder of Capitol Records. Weston formed an orchestra, adding strings and voices to big band ensembles to create what came to be called mood music. Mercer appointed him Capitol’s music director, and in 1944, after Stafford sang for 26 weeks on Mercer’s radio show, signed her as Capitol’s first contract singer.

She could deliver anything with grace. Nancy Franklin wrote in the New Yorker that she was “a highly educated folk singer working mostly in other idioms of American music”, who unconsciously used both operatic pitch vibrato and country and western volume vibrato. Stafford said she simply concentrated on “thinking the tone just before I make it… The voice is a muscle.”

Her first hit was a freak. She was in a studio corridor when Joe “Country” Washburn discovered he was minus a vocalist to record Tim-Tay-Shun (1947). Hidden behind the alias Cinderella G Stump, she sold a couple of million, without royalties. She otherwise chose in the 1940s from material laid before her (90 of her singles charted) or took advice from Weston. He did a full orchestral accompaniment in 1946 for The Nightingale, a song Anna had taught Jo. He retrieved the religious duet Whispering Hope from an old phonograph disc – Jo’s 1949 version, with Gordon Macrae.

Stafford was a character player, her own self ignored in the narrative of the number. She avoided live solo performances, initially because of her weight (at more than 13 stone she flopped at her only nightclub booking, New York’s Cafe Martinique, then dieted, achieving photographable size in time to switch from radio to television). She did not have and would not simulate an entertainer’s personality: “I wasn’t driven. I just loved what I did.”

Her engagement was with a microphone in subdued studio light, and through it, with listeners in distant darknesses. Her broadcasts for Radio Luxembourg and Voice of America made her “GI Jo” to US servicemen posted globally. She did record covers of second world war songs – I’ll Be Seeing You and No Love, No Nothin’ – but neither was released until 1959.

Stafford followed Weston when he left Capitol for Columbia in 1950, which subjected her to the novelty regime of Mitch Miller. At best, he supplied her with VistaVision scenarios, mostly recorded from 1950 to 1952 – You Belong to Me, Jambalaya, and Shrimp Boats. He also required her to cut turkeys – Chow Willy, and later Underneath the Overpass (1957). Her fine peak albums – American Folk Songs (1950) and Jo+Jazz (1960) – went unpromoted, and she was relieved to give up the 15 minutes of shivers that preceded TV broadcasts.

Her marriage to Pied Piper John Huddleston over, she converted to Catholicism and married Weston in 1952. They had two children, Tim and Amy, and settled in Beverly Hills.

Stafford and Weston got their revenge on Miller anyway. After recording his worst, she and the band reprised them as they deserved, with Stafford squarely missing each note. Then, at a Columbia sales convention in 1957, Weston dined with A&R staff in a restaurant with a bad piano player. Weston mimicked the pianist’s meandering hands and crumbling thirds. The A&R people imagined an album of this ineptitude – Paul would be “Jonathan Edwards”, Jo his chanteuse wife “Darlene”.

The resulting discs – The Original Piano Artistry of Jonathan Edwards (1957) and its sequels – were bestsellers, even after Time magazine outed their perpetrators. Jo admired Darlene’s quartertones and the fifth beat she added to a 4/4 bar for “an extra stride”.”She’s a nice lady from Trenton, New Jersey, and she does her best,” said Jo of Darlene, otherwise “the only singer to get off the A train between A and B-flat”. The album Jonathan and Darlene in Paris won Stafford’s only Grammy – for comedy in 1960.

The following year the couple spent the summer in London, recording the last series of the Jo Stafford Show for the ATV network.

When in the late 1960s, her voice no longer met her standards – the red needle on the meter must not flicker – she retired, performing one last time, safely in a group, at a tribute to Frank Sinatra (and again as Darlene, for charity). Until his death in 1996, Weston managed the couple’s Corinthian label, which reissued their recordings. Darlene’s pitch was even more challenged when digitally remastered.

Stafford’s offduty passion was the history of the second world war. She knew where the boys had been. A naval officer once contradicted her on a detail of a Pacific action, saying: “Madam, I was there!” A few days later he wrote to apologise. He had consulted his logs. He was wrong.

She is survived by her two children, both of whom went into the music business.

· Josephine Elizabeth Stafford, singer, born November 12 1917; died July 13 2008

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.