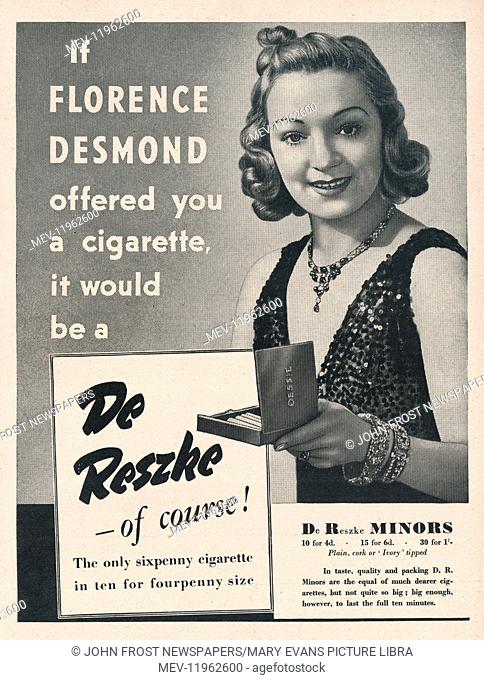

Florence Desmond was born in London in 1905. She was known prinarily for her stage performances but she did star also in films. Her first film in 1930 was “The Road to Fortune”. She made a film in Hollywood. Her last film was “Some Girls Do” in 1969. Florence Desmond died in 1993.

Her “Independent” obituary:

Florence Desmond certainly tackled the easy ones – Bette Davis, Marlene Dietrich, Katharine Hepburn, Greta Garbo – but it was with a satirical talent which other impersonators lack. She could draw a whole portrait with just a few strokes. I was delighted to come across her some years ago at the National Film Theatre in a Will Rogers vehicle, Mr Skitch. She played an English actress called Florence Desmond whom Rogers and family encounter in a trailer-park. She was on her way to Hollywood, she said, hoping to break into movies as an impersonator – and she did a stunningly accurate and funny Garbo and Zazu Pitts. The film was made in 1933, and she was in it because someone at Fox had seen her on the London stage.

She had already appeared in New York. She had started her career as a child dancer at the age of 10. Just out of her twenties she was appearing solo and in cabaret with Naunton Wayne. In 1928 she appeared in the Cochran revue This Year of Grace, written by Noel Coward, and she went with it when Coward and Beatrice Lillie took it to New York, understudying Lillie and performing ‘Dance, Little Lady’ with Coward. Over the next dozen or so years she consolidated her position as one of the brightest stars of the London stage, also appearing in variety and doing several stints as principal boy in pantomime. She was among the stars of the Royal Variety shows of 1937 and 1951.

Eventually it had become clear that while she was equally efficient as singer or dancer she was unique as an impersonator. It was in that capacity that she took New York by storm in what was said to be her debut there, at The Blue Angel night-club in 1946. The New York World-Telegram noted that ‘(Her) name is as much a household word in England as Gracie Fields’ or Beatrice Lillie’s’ – names advisedly chosen since these were two of her most brilliant impressions. After only three days her engagement was doubled. What she did then was what she did in her music-hall act – play all the guests at a Hollywood party. She moved from one to the other, using the minimum of props – gloves, a scarf – and miming drinking, smoking or the removal of glasses. She was as witty as she was accurate. As James Gavin says in his book on the clubs of that era,

Her most celebrated impression was of Hildegarde. Desmond entered with an armful of dying zinnias, which she dumped on the piano as she took her place on the bench. Lowering her head with a perplexed look, she found enough correct keys to approximate a Rachmaninoff prelude. Then scooping up some crumbling flowers, she stepped to ringside and smiled at an elderly man seated with his wife: ‘Tell me, the man in the grey flannel suit, are you in love?’.

I saw Hildegarde on the stage for the first time just two years ago, but have known her since childhood because of Desmond; 50 years I had waited to see Hildegarde pull off her elbow-length gloves the way Desmond did. There was neither ridicule nor malice in Desmond’s art – though I will make one exception, her job on Elisabeth Bergner in the 1940 Max Miller movie, Hoots Mon] She exaggerated that lady’s affectations, already too much, so that had Bergner seen them she would have retired on the spot. In that film she also did Cicely Courtneidge (just before her appearance at The Blue Angel she had taken over from Courtneidge in the musical Under the Counter), Davis specifically in Jezebel and Syd Walker. She wasn’t afraid to take on the men, and did a delicious parody of Noel Coward and Gertrude Lawrence in Private Lives.

But she was mainly affectionate. In 1948 a packed house at the Palladium was waiting to see Betty Hutton, heading the bill and making a sensational success of it. Desmond closed the first half offering, as we expected, her Hollywood party. Suddenly and audaciously she changed herself into Hutton, something a lesser artist would never have dared or got away with. But that was why we cherished her: not for the Hepburns and Tallulah Bankheads, but for those the others never attempted – Claudette Colbert, Barbara Stanwyck, Myrna Loy.

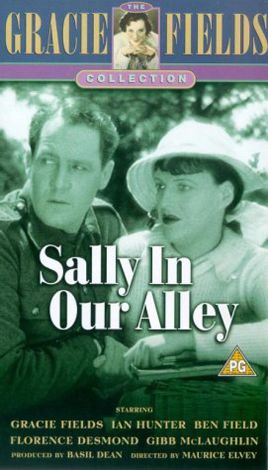

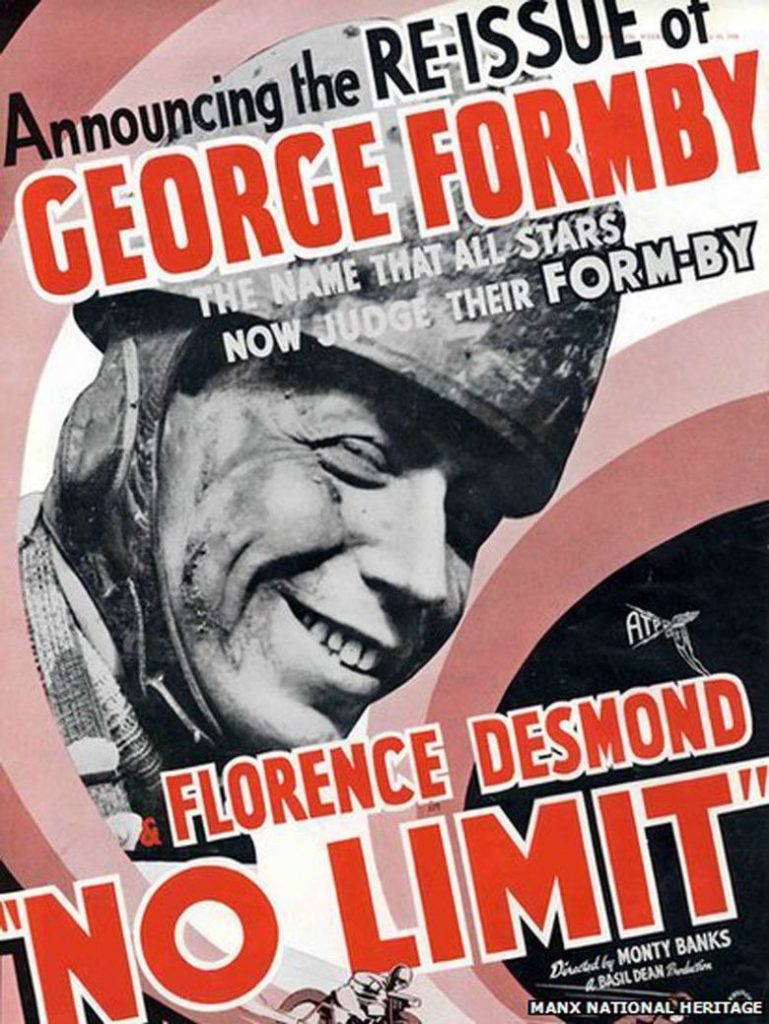

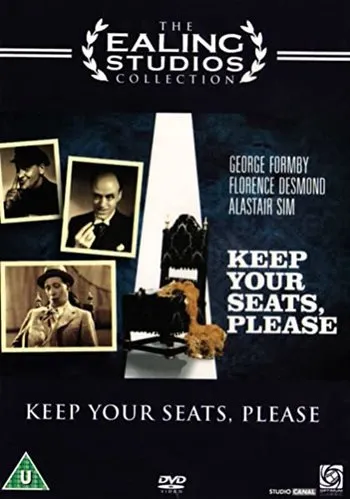

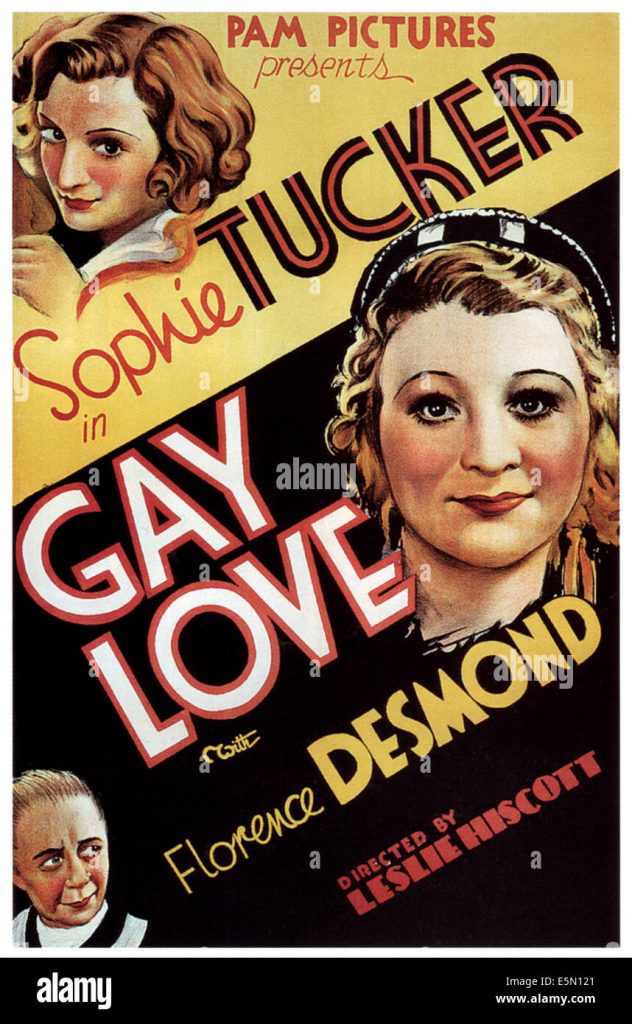

Even so she was simply too good an actress and comedienne to limit herself. ATP – the forerunner of Ealing – cast her as George Formby’s leading lady in his first important movie, No Limit (1935), and again in Keep Your Seats Please] (1936). Also in 1936 she played a temperamental French singer in Accused, with Douglas Fairbanks Jnr – so temperamental, in fact, that she gets murdered in reel two. After a long absence from the cinema she played a serious role in Three Came Home (1950), produced and written from Agnes Newton Keith’s autobiographical book by Nunnally Johnson and directed by Jean Negulesco. Keith was played without glamour by Claudette Colbert, and Desmond made a handsome contribution as her best friend in the internment camp.

After her debut at the Blue Angel, Desmond was as much in demand in the US as in Britain. She was one of the handful of cabaret performers to be seen time and again – unlike, say, Marlene Dietrich – because she was very funny and seldom the same twice. The golden age of the New York night-club ended, if not as quickly and decisively as the British music hall. Desmond appeared occasionally on television for a while. In 1952 she was in a play at the Comedy, The Apples of Eve, in fact taking on seven different roles. A little later her name disappeared from the trade reference books. We supposed she had retired, which she confirmed in a radio interview only about five years ago. Yes, she said, she was happily married and she had nothing to prove to anybody any more.

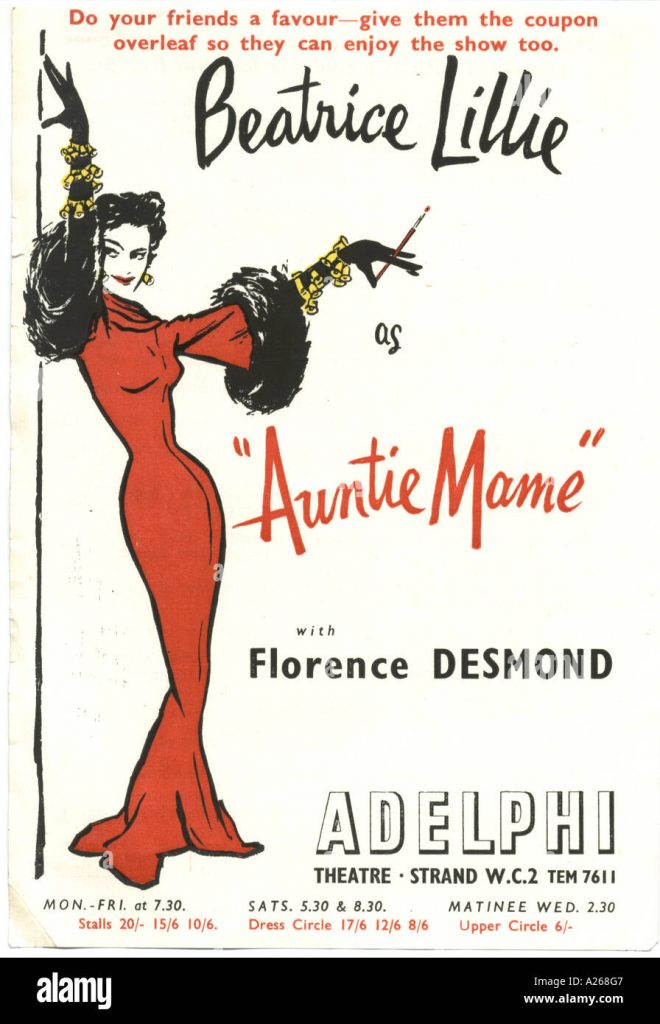

Apart from two late film appearances – Charley Moon (1956) and Some Girls Do (1958) – she came out of retirement just once, in 1958, to appear in Auntie Mame, at the Adelphi, opposite Beatrice Lillie’s Mame, as her friend and rival Vera Charles. Doubtless she was paid a small fortune to do so, since, by Coward’s own account, Lillie was so undisciplined in 1928 that he wanted ‘to wring her neck’ and she didn’t improve with the years. This was noticeable on stage, if hilariously so, but she was more precise in her scenes with the needle-sharp Desmond.

The above “Independent” obituary can be accessed online here.