Maureen O’Hara’s Obituary in “The Guardian”

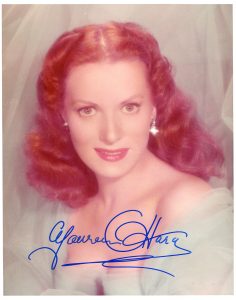

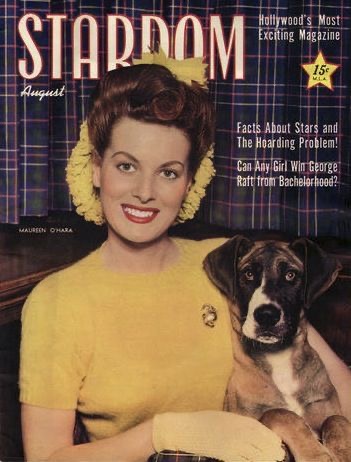

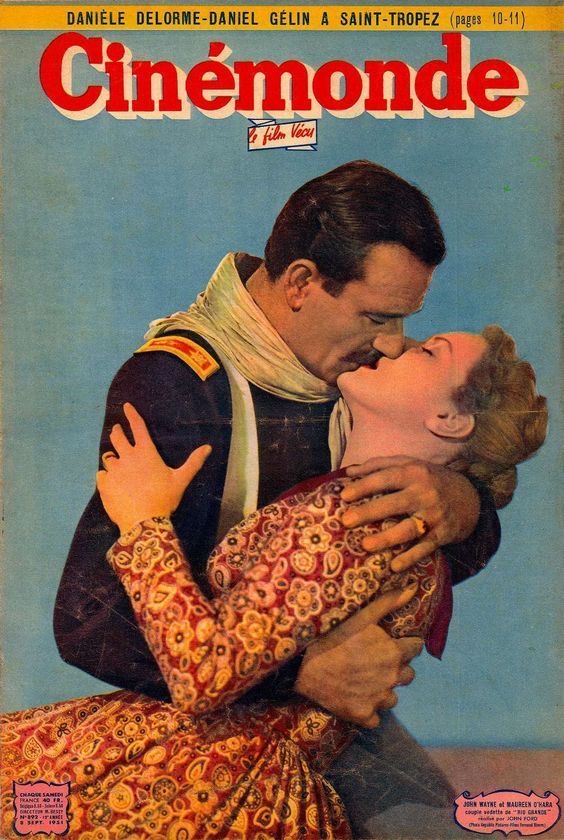

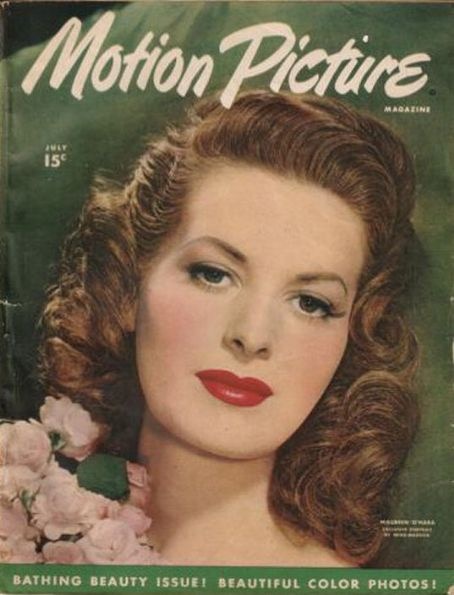

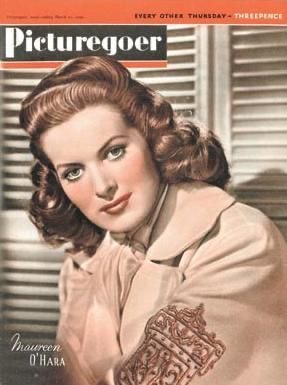

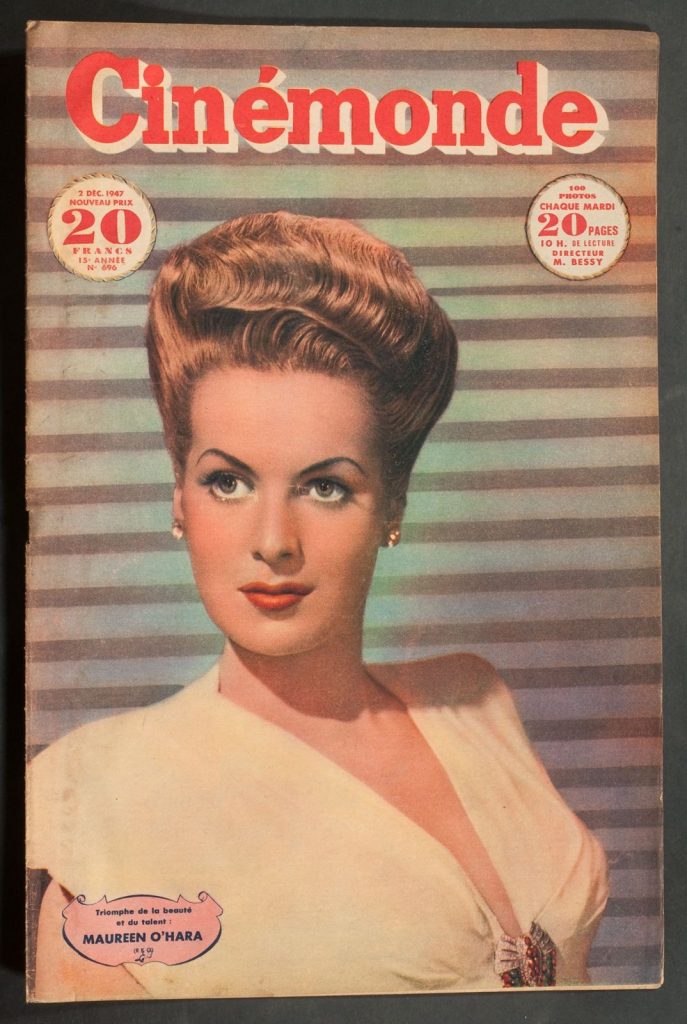

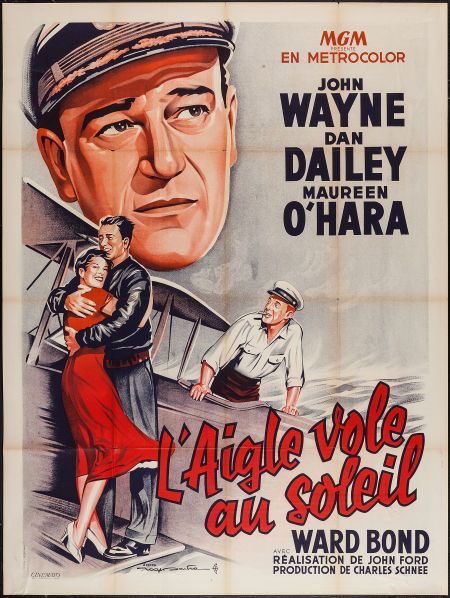

In the early 1950s the prevailing image of Maureen O’Hara, who has died aged 95, was one of a feisty heroine, red hair blazing, who was more than a match for her male co-stars. Big John “Duke” Wayne, whom she partnered in five films, said of her: “I’ve had many male friends in my life except for one, O’Hara; and she’s a great guy.”

The great director John Ford, with whom she also worked so often, referred to her as “a man’s kind of woman”.

In The Quiet Man (1952), Ford’s Irish pastoral-romantic-comedy, the blue-bloused, scarlet-skirted, bare-footed O’Hara, as Mary Kate Danaher, is first seen by Wayne as she tends her sheep. “Hey, is that real?” he asks. “She couldn’t be.”

At their second meeting Wayne tries to kiss her, and she tries to sock him. “Watch that scene, and you’ll see Duke put his hand up,” O’Hara once said. “He deflects my blow because he knew me so well. He knew I was for real. I was hitting him.”

Wayne’s defensive action had unintended consequences. “The pain went up under my armpit,” she said. “[Afterwards] Duke came up to me and said, ‘godammit, you nearly knocked my head off. Let me see your hand.’ Each finger was like a sausage [and] they sent me to hospital.”

Ford declared O’Hara to be “the best bloody actress in Hollywood”. She certainly was not that, but Ford, who had Irish roots, brought out her warmth and “Irishness,” and she became an important element in his repertory company.

Their relationship was never easy, but O’Hara loved the results of working with him. “So many films we made crying in our heart as we went to work every day,” O’Hara recalled, “but a great role in a great movie with somebody like John Ford was never difficult. That was heaven, even though you wanted to kill him.”

O’Hara was born Maureen FitzSimons, the second of six children, in a suburb of Dublin. Her mother was an accomplished contralto, and her father, a businessman, part-owned Shamrock Rovers football team. “We grew up on sport and music. All the great singers that would come to visit Dublin would come to our house for a musical evening,” she said. “We six kids, we used to sit at the top of the stairs and listen.”

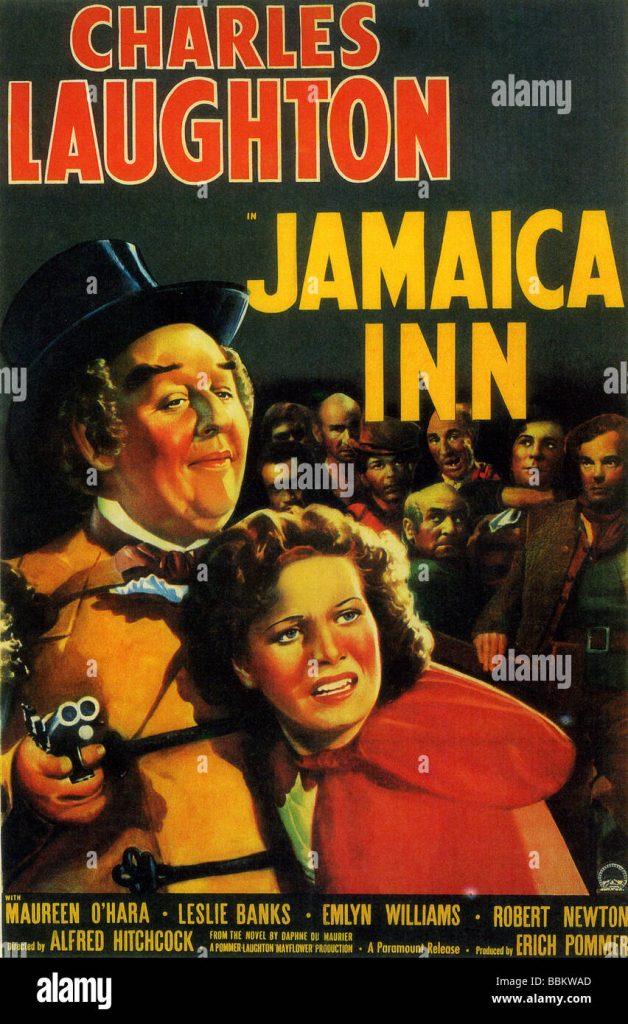

Maureen was torn between wanting to be an opera singer or a football player. In the end she settled for acting, having been accepted by Dublin’s Abbey theatre at the age of 14. Three years later, during her theatrical training at the Abbey, she received a request to travel to London for a screen test at Elstree studios. As a result she landed two bit parts but, more significantly, she impressed the actor Charles Laughton, who could not forget her “hauntingly beautiful eyes”. Laughton and the producer Erich Pommer, the co-founders of Mayflower Productions, offered her a seven-year contract, and changed her name to O’Hara. Her first role was as a naive orphan girl involved with Cornish smugglers in Alfred Hitchcock’s corny Jamaica Inn (1939), opposite Laughton as the lip-smacking squire. On the set of that film she met the English film producer George Brown, whom she married that year at the age of 19. The marriage ended in divorce only two years later.

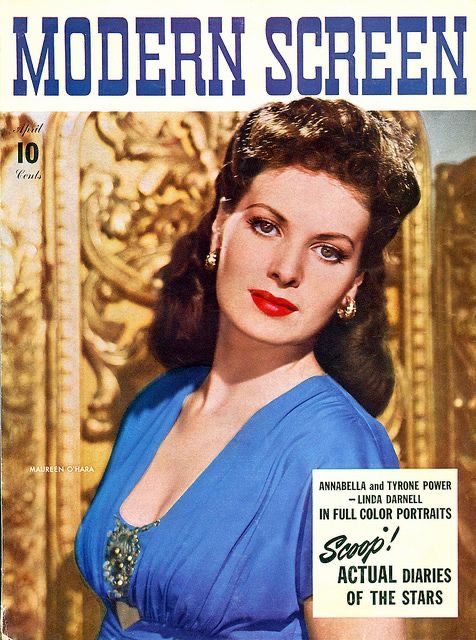

In 1939 Laughton also persuaded RKO studios to cast O’Hara as the Gypsy girl Esmeralda to his Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame. She gave both a sensual and touching portrayal, which immediately established her as a Hollywood star. Her career from then on was divided between colourful escapist entertainments and more serious black-and-white efforts.

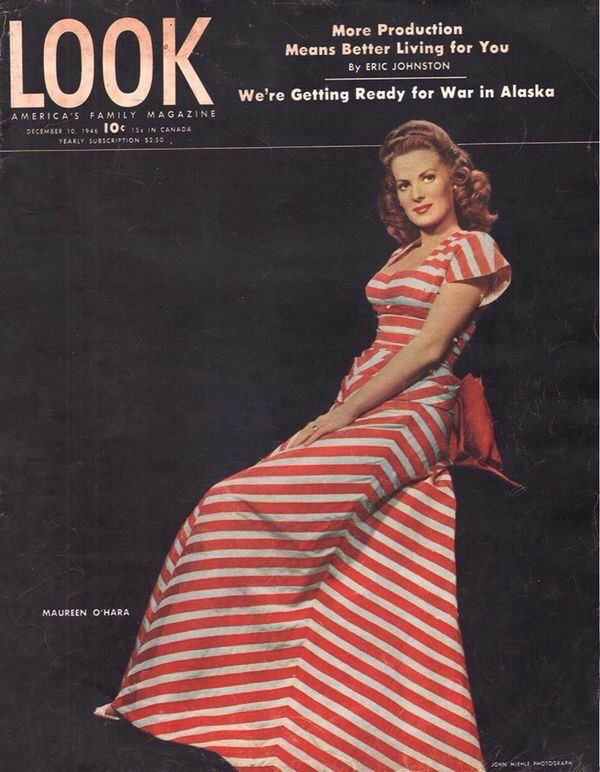

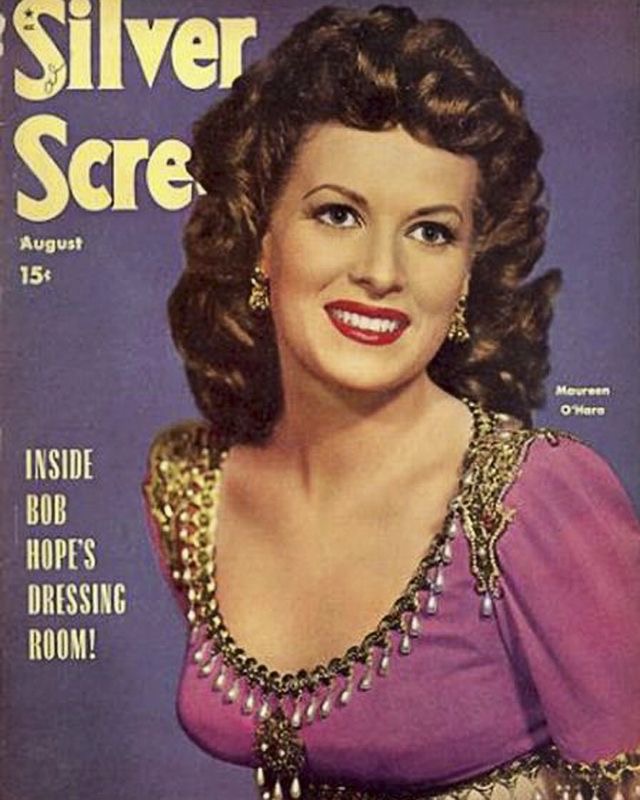

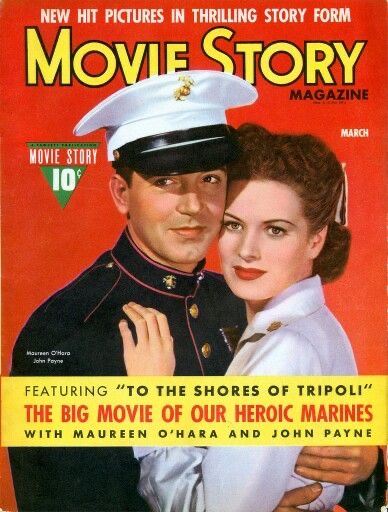

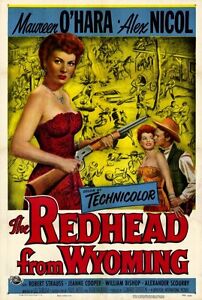

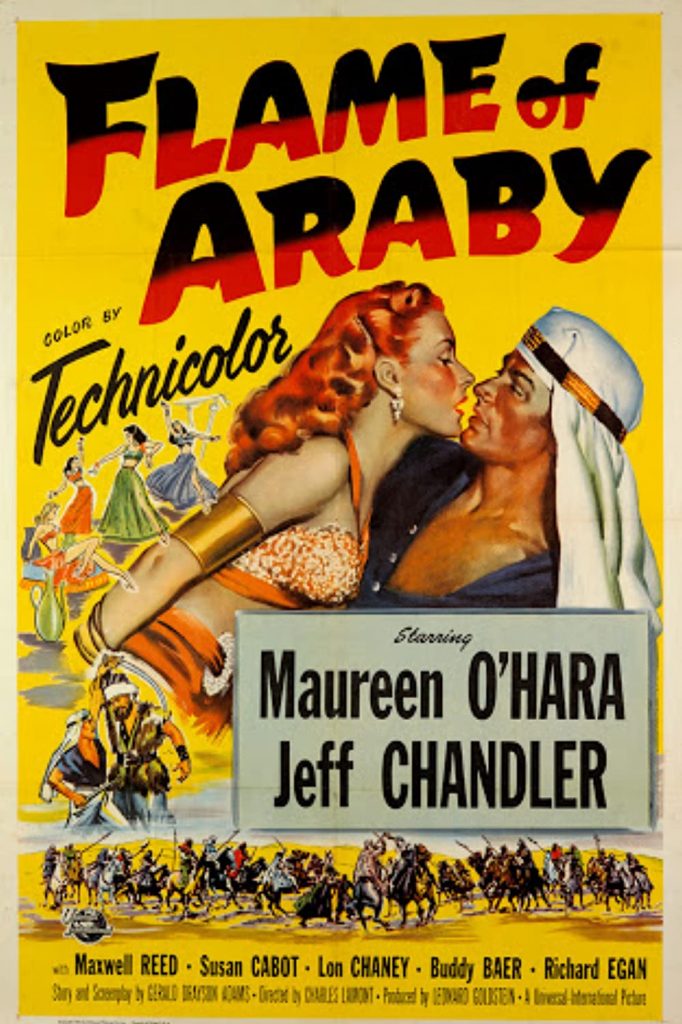

Among the former were piratical and exotic adventure yarns such as The Black Swan (1942), The Spanish Main (1945), Sinbad the Sailor (1947), Bagdad (1949) and Tripoli (1950), the latter directed by Will Price, whom O’Hara married soon afterwards. In most of these films she was rescued from the villain by the hero, though the villain often seemed more in need of rescuing from her. O’Hara’s spirited character stretched the limits of Hollywood’s macho conventions. Dorothy Arzner’s Dance, Girl, Dance (1940) has been championed by feminists because of the final scene when O’Hara, as a chorus girl, having submitted unwillingly to the role forced upon her, berates the audience of leering males. However, despite her celebrated monologue, which she delivers with passion, she eventually gives up her dreams of becoming a ballet dancer in favour of marriage.

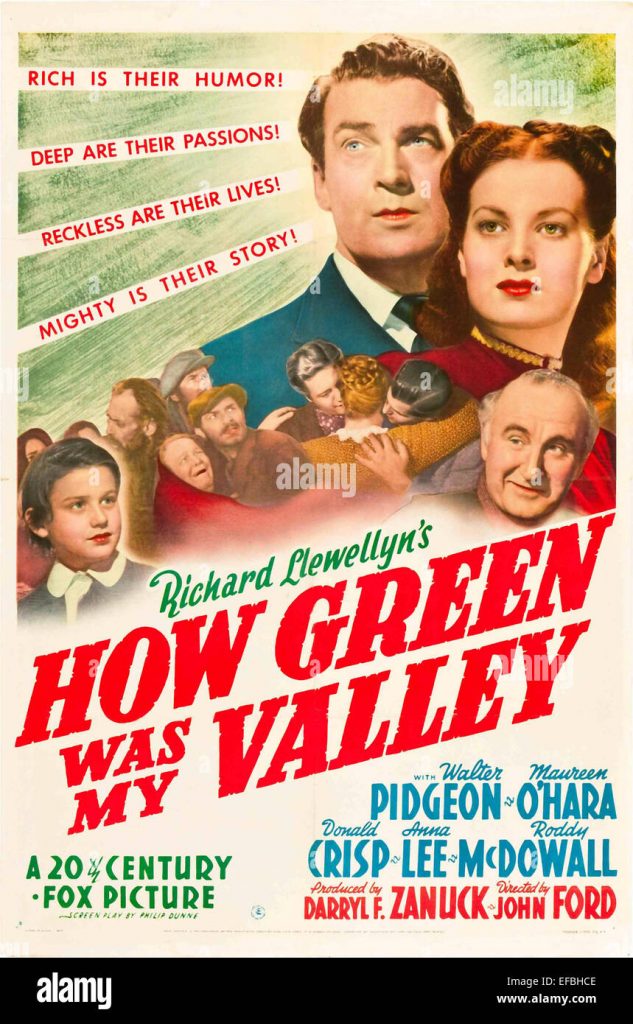

In 1941, O’Hara played her first part for Ford in How Green Was My Valley, set in a Welsh mining town, in which her Irish accent, Donald Crisp’s Scottish and Walter Pidgeon’s American served for a Welsh accent. As Angharad Morgan, O’Hara has mostly to look beautifully lovelorn during her abortive romance with the pipe-smoking preacher Pidgeon, but has a fine scene with him in which she defends a single mother from attack. “What do the deacons know about it? What do you know about what could happen to a poor girl when she loves a man so much that even to lose sight of him for a moment is torture!”

O’Hara was often an exemplar of noble and defiant womanhood, not least in Jean Renoir’s This Land Is Mine (1943). In it, she was reunited with Laughton, who plays a mother-dominated schoolteacher secretly in love with O’Hara, a colleague who is working for the wartime resistance.

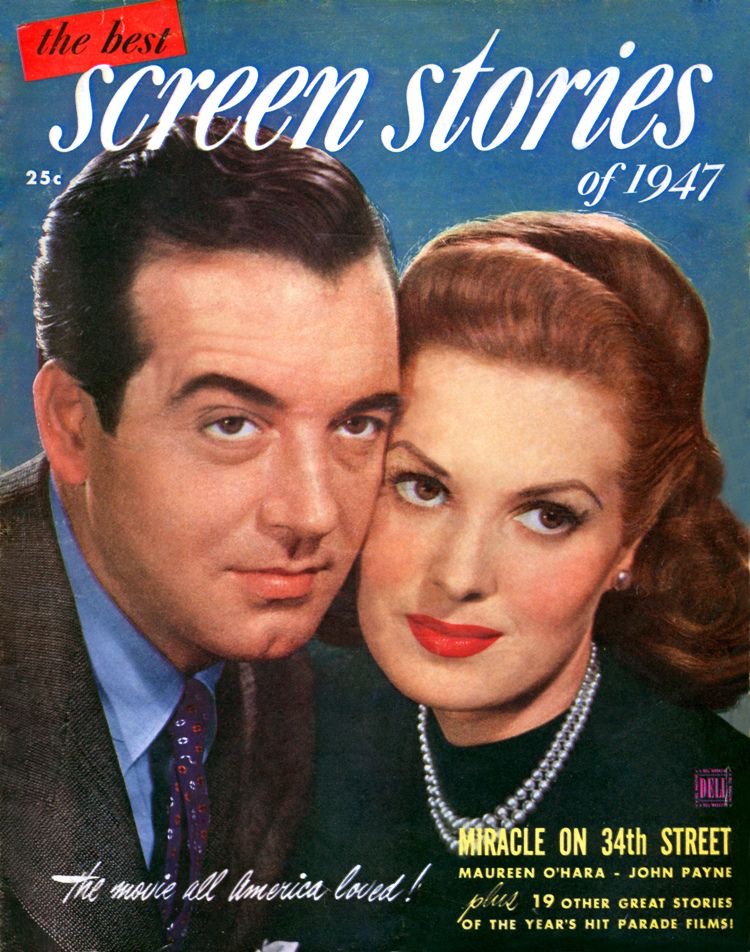

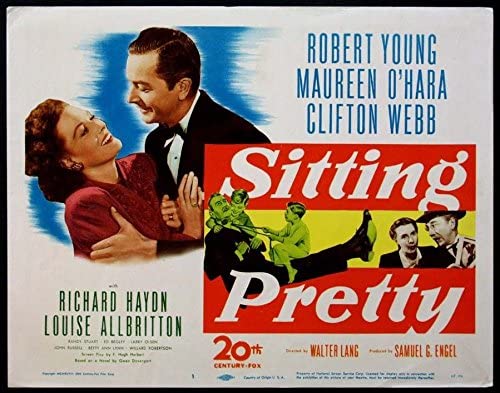

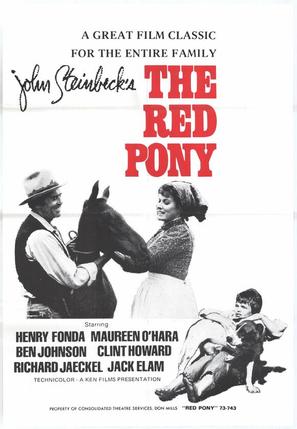

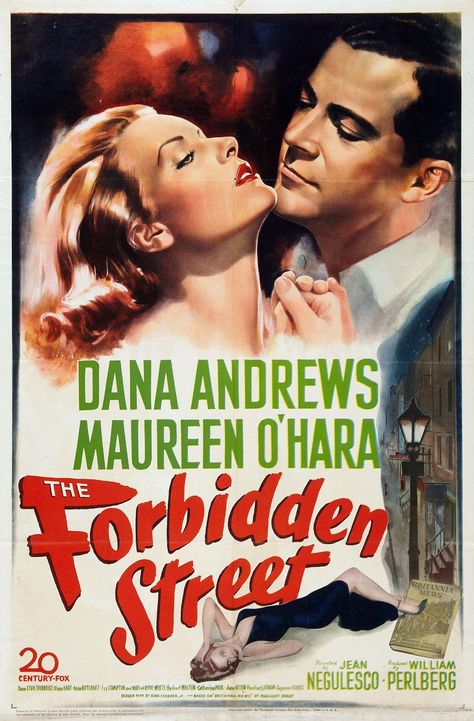

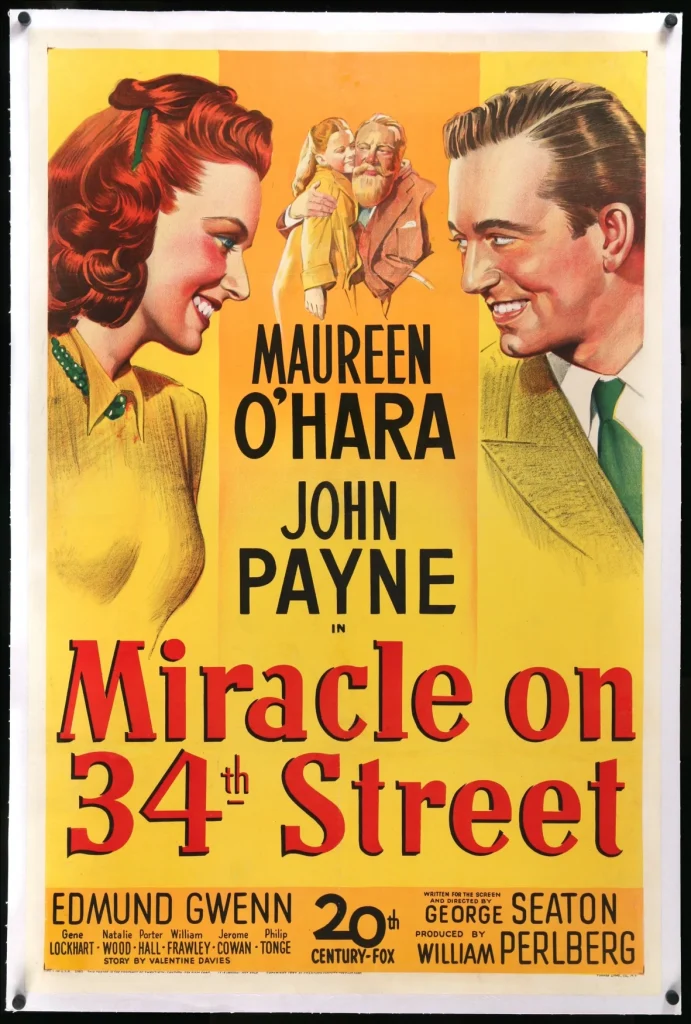

Now a resident star at 20th Century-Fox, O’Hara proved the perfect middle-class wife in Sentimental Journey (1946), Miracle on 34th Street (1947) and Sitting Pretty (1948). But she was her tempestuous self again as a Southern belle in the period piece The Foxes of Harrow (1947), and in Rio Grande (1950), the last of Ford’s cavalry trilogy, in which she played the estranged Confederate wife of a Yankee colonel (Wayne), fighting over their son.

O’Hara played quite a few estranged wives, providing her with the opportunity to be sassy; battling over her twin daughters with Brian Keith in The Parent Trap (1961), and again with Wayne in McLintock! (1963), the latter containing a rerun of the taming-of-the-shrew theme from The Quiet Man, with Duke giving her a spanking in the distinctly non-feminist finale.

The last film she made for Ford was The Wings of Eagles (1957), in which she played the long-suffering wife of a war hero pilot (Wayne). Eleven years later the divorced O’Hara, with a grown-up daughter, married Charles Blair, a famous aviator.

She retired from films a few years later to live in the Virgin Islands and run a commuter sea plane service, Antilles Airboats, with her husband. “I got to live the adventures I’d only acted out on the Fox and Universal lots,” she said. However Blair was killed in a plane crash in 1978. She then became head of the company, the first woman president of a scheduled airline in the US.

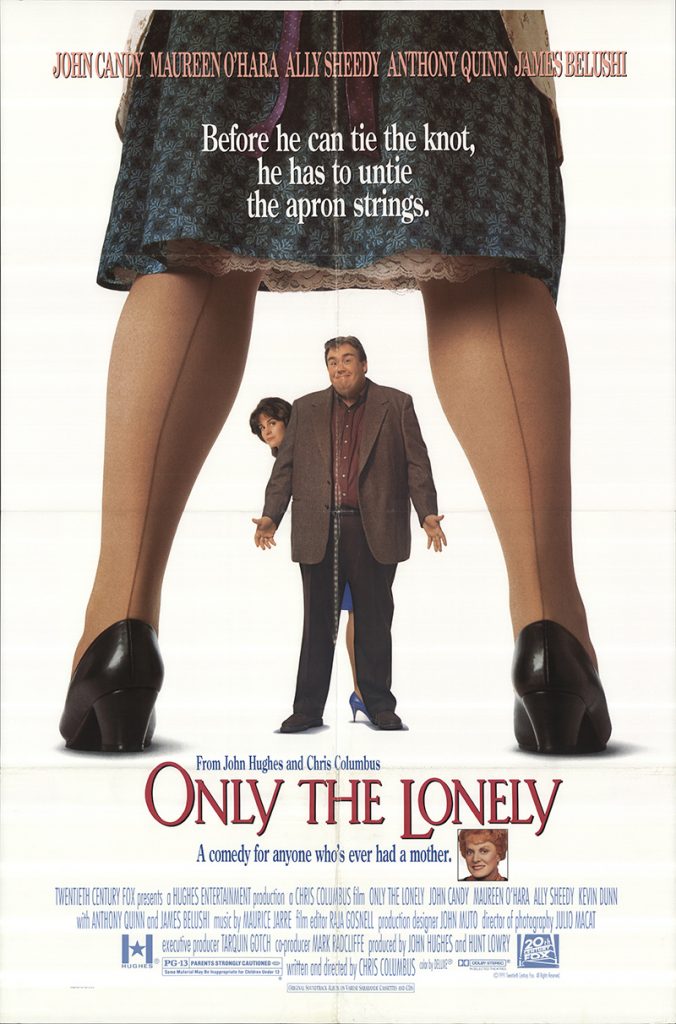

Fortunately she was coaxed out of her 20-year retirement in 1991 to appear as John Candy’s domineering Catholic mother in Only the Lonely – she acted everyone else off the screen, a reminder of just how much the cinema had missed her. After that she appeared in three TV movies, including The Last Dance (2000), in which she played a retired teacher.

In 2005 she moved back to Ireland, settling in her house on a 35-acre estate, Lugdine Park, in west Cork, which she had bought with Blair in 1970. In 2012 she returned to the US to be closer to her family as her health declined.

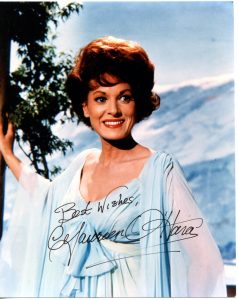

Although O’Hara was never nominated for an Oscar, she received an honorary Academy award in 2014 in acknowledgment of a lifetime of performances that “glowed with passion, warmth and strength”.

She is survived by her daughter, Bronwyn, from her marriage to Price, and by a grandson and two great-grandchildren.

Maureen O’Hara, actor, born 17 August 1920, died 25 October 2015