Robert Evans. TCM Overview.

Robert Evans is a reknowned film producer in Hollywood. However in the 1950’s he had a career as a movie actor. He made his debut in 1957 in “The Sun Also Rises” with Tyrone Power and Ava Gardner. His other films include “Man of A Thousand Faces” with James Cagney and Dorothy Malone and then as part of an all star cast in “The Best of Everything” which aso starred Joan Crawford, Stephen Boyd, Brett Halsey, Suzy Parker and Diane Baker. His most famou acting role was in “The Fiend Who Walked the West” with Dolores Michaels.

TCM Overview:

Perhaps one of the most notorious personages ever to grace motion pictures, producer and former Paramount Pictures studio head Robert Evans blazed a trail through Hollywood that left behind numerous fractured marriages, countless heartbroken starlets, several friends-turned-enemies, and a career brimming with some of the best movies ever made. After receiving his start as an actor in movies like “The Sun Also Rises” (1957) and “The Best of Everything” (1959), Evans turned to producing in the late-1960s, which quickly led to becoming a powerful executive at the struggling Paramount Pictures. Almost immediately, Evans had a profound effect on the studio’s bottom line, churning out hits like “Barefoot in the Park” (1967), “The Odd Couple” (1968) and “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968). In the following decade, he steadied Paramount’s fortunes with huge hits like “Love Story” (1970) and “The Godfather” (1972), before leaving the studio to branch out on his own as a producer with “Chinatown” (1974).

Following up with “Marathon Man” (1976) and “Black Sunday” (1977), Evans seemed impervious to failure. But in 1980, following a cocaine bust and the ridicule endured from producing “Popeye” (1980), Evans hit a career slump that ended with him broke and ostracized from Hollywood. The final straw was “The Cotton Club” (1984), a huge flop that was mired in production excesses that also included the murder of a financier, for which Evans was briefly implicated. Sinking further into debt, depression and cocaine addiction, Evans languished in obscurity for the remainder of the decade. He reemerged with the misfire “Chinatown” sequel, “The Two Jakes” (1990), and spent the rest of the 1990s making critical and financial disasters like “Sliver” (1993), “Jade” (1995) and “The Saint” (1997). He earned a degree of cult status following the self-narrated documentary “The Kid Stays in the Picture” (2002), which introduced Evans to a new generation while reminding older crowds just how integral he had been to one of cinema’s most vibrant eras.

Born on June 29, 1930 in New York City, Evans grew up in a comfortable home headed by his father, Archie Shapera, a dentists, and his mother, Florence, a homemaker. As a child, Evans performed on numerous radio shows – some 300 all told – including “Archie Andrews” (NBC, 1943-1953), “The Aldrich Family” (NBC/CBS, 1939-1953) and “Gang Busters” (NBC/CBS, 1935-1957). Following his television debut on “Elizabeth and Essex” (1947), he went into business with his brother, Charles, and his partner, Joseph Picone, with the fashion company Evans-Picone, for which he did their promotional work. Moving to Hollywood some years later, Evans was lounging poolside at the Beverly Hills Hotel, where he was spotted by Golden Age actress, Norma Shearer, who thought him to be a dead-ringer for her deceased husband, Irving G. Thalberg, which happened to be a role in the biopic of actor Lon Chaney, “Man of a Thousand Faces” (1957). Shearer successfully lobbied for Evans to get the part, which wound up becoming his feature debut. Evans went on to appear as Pedro Romero in an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s “The Sun Also Rises” (1957), despite objections raised by star Ava Gardner and even the author himself.

Continuing his attempt to make it as an actor, Evans enlisted the help of famed acting coach, Stella Adler, for the audition for a supporting role in the relationship melodrama “The Best of Everything” (1959), which helped him land the part. Despite managing to make strides on screen, Evans remained largely dissatisfied with his career. He decided instead to move into producing by joining 20th Century Fox, where he set up “The Detective” (1968) with Frank Sinatra starring as a tough cop is sent to investigate the murder of a department store magnate’s son. Featuring a strong performance from Sinatra, the gritty crime thriller became one of the biggest box office successes of the year. He left Fox to take a studio executive job at Paramount Pictures in 1966, where he served as the Vice President of Production and almost immediately began to turn the ailing studio’s fortunes around, despite his lack of experience. Evans had his first hit with the winning romantic comedy, “Barefoot in the Park” (1967), which starred Robert Redford and Jane Fonda as a pair of newlyweds adjusting to their new lives together. Staying with Neil Simon’s source material, Evans produced another hit with “The Odd Couple” (1968), which pitted Walter Mathau and Jack Lemmon as polar opposite roommates living together in Manhattan.

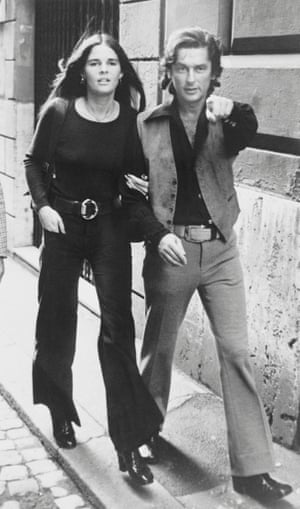

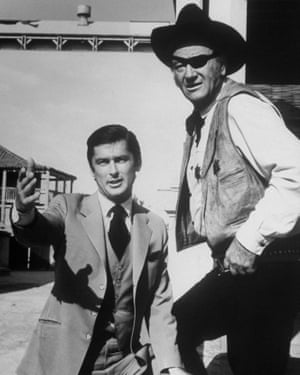

Evans’ power at Paramount only grew when he steered “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968) to the big screen, director Roman Polanski’s disturbing horror movie about a young wife and mother (Mia Farrow) who grows to realize that her soon-to-be child is not of this world. His unbelievable run continued with the easygoing crime caper, “The Italian Job” (1969), starring Michael Caine, and the charming Western “True Grit” (1969), which starred John Wayne in his only Oscar-winning role. He had his biggest hit with his next film, “Love Story” (1970), which starred Ryan O’Neal and Evans’ real-life wife Ali McGraw as a pair of mismatched lovers who manage to stick together despite the objections of his father (Ray Milland), only to suffer tragic consequences. Though critics were divided, “Love Story” was a big success with audiences, as the picture became the highest-grossing movie made by Paramount up to that point. The film also earned seven Academy Award nominations, including one for Best Picture. Meanwhile, Evans and McGraw – who happened to be his third wife at this point – had son Josh Evan in 1971.

Also that year, having almost singlehandedly pulling Paramount back from the brink, Evans was given the reigns of the entire studio and named top dog as Executive Vice-President in charge of worldwide production at the studio. He next proceeded to steer “The Godfather” (1972) through production, a process that began as far back as 1968, when a then-unknown author named Mario Puzo brought pages from his unpublished manuscript, Mafia, to Evans in hopes of securing a payday to cover what he owed to bookies. At least that was how Evans claimed the story went. Others connected to the movie claimed it was brought to Paramount through other channels. Regardless of how the manuscript ended up at the studio, there was no doubt that Evans was integral to getting the picture made. In order to make an authentic film about the Italian Mafia, Evans insisted on an Italian-American director. After finally settling for Francis Ford Coppola when most other bigger names had passed on the project, Evans and his new director clashed mightily over which actors to cast. With Coppola championing Al Pacino as Michael Corleone and Marlon Brando as Don Corleone, Evans was pushing for the likes of Warren Beatty and Danny Thomas for Vito, telling Coppola, “A runt will not play Michael.” (Vanity Fair, March 2009). Coppola ultimately won the battle.

Through the course of production, Evans and his producers were plotting to fire Coppola, due to cost overruns and an inability to stay on schedule. Because of his numerous tangles with the director throughout the production – already proving difficult due to death threats from actual mobsters before producer Albert Ruddy smoothed things over – Evans cemented his reputation for being antagonistic towards filmmakers. Regardless of the great difficulty in getting the film made, “The Godfather” proved to be the massive hit Paramount was looking for. The crime saga depicting the decline of an older generation of mobsters in favor of the new was also a big hit with critics, winning three Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Throughout the years, Evans became known for personally coveting credit for the success of the film created under his watch, although the extent and merits of his contributions were routinely debated. Meanwhile, Evans and wife Ali McGraw divorced in 1972 after she fell for her co-star, Steven McQueen, in “The Getaway” (1972). Evans later attributed his near-obsession with seeing “The Godfather” through to completion as the straw that broke the camel’s back. He soon followed up with “Serpico” (1973), director Sidney Lumet’s gritty crime drama about rookie police officer Frank Serpico (Al Pacino), whose attempts to shed light on a corrupt system leads to his ultimate downfall. The film went on to became yet another 1970s classic that the high-flying Evans could count as his own.

Evans next steered the financially successful, but critically underappreciated adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s iconic novel, “The Great Gatsby” (1974), which starred Robert Redford as the self-made Gatsby, Mia Farrow as the superficial Daisy Buchanan, and Sam Waterston as the naïve Nick Carraway. Working again with the excitable Coppola, Evans helped shepherd “The Godfather, Part II” (1974) and “The Conversation” (1974) to the big screen. Both were hits, both were critically hailed, and both became staples of 1970s cinema. But it was “The Godfather, Part II” which earned the greatest distinction after winning six Academy Awards, including one for Best Picture. Evans left the studio top spot and became an independent producer in 1974, a highly successful stint that started with producing director Roman Polanski’s classic neo-noir “Chinatown” (1974), a lush, cynical and serpentine neo-noir set in 1930s Los Angeles. The film starred Evans’ close friend, Jack Nicholson, who portrayed Jake Gittes, a dogged private eye whose search for the murderer of a water department official pulls him into a much darker and more sordid scandal involving the official’s wife (Faye Dunaway) and her despicable father (John Houston). After receiving 11 Academy Award nominations, “Chinatown” only took home one for Robert Towne’s Best Original Screenplay. Nonetheless, the film was considered to be one of the best ones made in that period, while Towne’s script was held up as being the best ever written.

Evans continued his unparalleled run with the John Schlesinger thriller “Marathon Man” (1976), starring another longtime pal, Dustin Hoffman, who later had a falling out with the producer over his undeniable impersonation of Evans with his character in “Wag the Dog” (1997). He moved on to produce John Frankenheimer’s popular thriller “Black Sunday” (1977), which featured a stunning climactic scene involving a blimp at the Super Bowl, and the rather underwhelming romantic drama, “Players” (1979), which starred ex-wife Ali McGraw – a film he made while in the midst of a divorce with another wife, former Miss America Phyllis George. Evans entered the next decade on a high note with the country-themed hit “Urban Cowboy” (1980), which capitalized on the then massive popularity of its star, John Travolta, while generating a soundtrack some claimed help propel interest in the pop-country phenomenon that soon followed. But cracks began to appear in Evans’ seemingly impervious façade when he produced director Robert Altman’s unsuccessful and highly-ridiculed take on “Popeye” (1980), starring Robin Williams as the big-armed sailor who is fond of his spinach. Also that year, Evans ran into legal trouble when he was arrested and later convicted on a misdemeanor cocaine charge. Sentenced to probation, he was given the chance to wipe the slate clean with an anti-drug film called “Get High on Yourself” (1981), which he financed with his own money and cast with several famous actor friends.

Regardless of his public condemnation of drugs, Evans continued his habit unabated. In 1983, he became embroiled in further scandal while in the middle of making the period gangster piece, “The Cotton Club” (1984) with Francis Ford Coppola, when his business partner on the project, Roy Radin, was found murdered. Right from the start, “The Cotton Club” appeared doomed to failure. Initially, Evans wanted to direct the film himself, but decided not to and brought in a hopelessly broke Coppola in at the eleventh hour. Having spent some $13 million before Coppola even appeared, Evans resorted to finding money any way he could, including from notorious Saudi Arabian arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi, who was later complicit in the Iran-contra scandal. The budget ballooned to almost $50 million – a fortune at the time – while Evans became briefly implicated in Radin’s slaying (In 1991, cocaine dealer Karen Greenberger and three bodyguards were convicted of the crime). The film released to lackluster box office totals, throwing Evans into deep despair, which became exacerbated due to giving trial testimony and the fact that he was now flat broke.

Following an extended hiatus, Evans returned to active producing and corralled Nicholson to direct and star in the inferior, but interesting “Chinatown” sequel, “The Two Jakes” (1990), which failed to capture the attention of anyone at the time and fared poorly at the box office. He moved on to the Sharon Stone erotic thriller, “Sliver” (1993), which was nearly universally panned by critics while performing fairly well in theaters. Evans continued making critically maligned flops with “Jade” (1995), an erotic thriller from the juvenile mind of Joe Eszterhas that starred David Caruso as an assistant D.A. drawn into a murder case involving a sultry psychologist (Linda Fiorentino) and her prominent attorney husband (Chazz Palminteri). Though he received some critical kudos for the comic strip adaptation of “The Phantom” (1996), they were not enough to boost ticket sales. Critics lashed out at his next project, “The Saint” (1997), which starred Val Kilmer as amateur detective, Simon Templar, a character featured in a long-running book series that was previously turned into films, a radio show and even a successful British television series. Unable to rekindle his magic from the 1970s, Evans struck out again with a rather limp remake of the comedy classic, “The Out-of-Towners” (1999), starring Steve Martin and Goldie Hawn.

Though fallen out of prominence for some time, Evans’ illustrious career again came to the forefront with the documentary “The Kid Stays in the Picture” (2002). Based on the producer’s life as told in his revealing 1994 autobiography and narrated by Evans himself, the documentary pulled no punches in detailing his outlandish adventures in show business. The title referred to his near-firing from his role in “The Sun Also Rises,” a job that was saved by studio head, Darryl Zanuck, who watched Evans’ first take and made a portentous decree: “The kid stays in the picture.” The book itself was already a hit with Hollywood insiders, particularly the audio version that was narrated by Evans himself. The project came about when rising documentarian team Brett Morgen and Nanette Berstein worked with Evans – who was in the midst of recuperating from a debilitating stroke – in capturing the producer’s chaotic, but always fascinating life on film. Kaleidoscopic, mesmerizing, and entirely subjective, “The Kid Stays in the Picture” was roundly praised by critics, while opening a re-exploration into his works and creating an air of pseudo-celebrity that could only be best described as the Cult of Evans.

The popularity of the film even led Evans and Morgen to develop the animated series, “Kid Notorious” (Comedy Central, 2003-04), which adapted anecdotes from his life into wild cartoon exploits that mixed “South Park”-style scatological gags with snarky, knowing Hollywood insider humor. He also returned to the producing game with the romantic comedy “How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days” (2003), a minor hit that proved star Kate Hudson’s box office appeal in lightweight fare. Ever the lothario, Evans married in 2002 for a sixth time to Leslie Ann Woodward, a union that was dissolved after a mere eight months, though it was nothing compared to his nine-day marriage to previous wife, actress Catherine Oxenberg, in 1998. Evans next produced and appeared in the documentary “The Last Mogul” (2005), which detailed the life and career of former talent agent and studio executive, Lew Wasserman. Meanwhile, Evans appeared in spirit on the popular Hollywood series “Entourage” (HBO, 2004- ), in the form of Bob Ryan (Martin Landau), a legendary film producer fallen on hard times who is looking to make a comeback. Though initially offered to play the role himself, Evans bowed out, but graciously offered his Beverly Hills mansion as a location.

The TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

Robert Evans obituary in “The Guardian” in 2019.

Robert Evans, who has died aged 89, was an extravagant film producer whose exciting, glamorous and sometimes grotesque life threatened frequently to overshadow the movies he made. As head of production at Paramount Pictures in the late 1960s and early 70s, the former actor was responsible for reviving the fortunes of that moribund studio by overseeing hits such as Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Love Story (1970), The Godfather (1972) and Chinatown (1974).

Robert Evans, celebrated Hollywood producer of Chinatown, dies aged 89

Read more

There was no shortage of stories to feed Evans’s larger-than-life image. He cherished and bragged about his friendships with Henry Kissinger, Warren Beatty and Ted Kennedy. He lived in a 16-room Regency house in Beverly Hills and dispatched bottles of Dom Perignon as quickly as he got through sexual partners.

According to Peter Biskind’s 1998 account of 70s Hollywood, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, a housekeeper would bring Evans breakfast in bed each morning accompanied by a piece of paper on which she had written the name of whichever woman happened to be lying beside him. He was married seven times, most famously in 1969 to Ali MacGraw, the star of Love Story, who left him four years later for Steve McQueen. One marriage, to the actor Catherine Oxenberg, lasted for only 12 days.

This life of excess, including an addiction to cocaine, eventually ruined Evans’s career: he went from being worth $11m in 1979 to having $37 to his name 10 years later. In 1980, he was given a suspended prison sentence for cocaine trafficking. As part of his plea bargain, he agreed to make an anti-drugs public information message.

What started as a commercial became a week of star-studded TV specials instigated by Evans. He ploughed $400,000 of his own money into the campaign, which included the tuneless, anodyne celebrity singalong Get High on Yourself. He later admitted that he was still taking cocaine while this media blitz was under way.

He had always idolised and fraternised with gangsters (he was close friends with the mob lawyer and Hollywood “fixer” Sidney Korshak). In 1983, Evans’s life spilled over from the showbusiness pages to the crime ones when he became a suspect in the murder of the producer and promoter Ray Radin, who was involved with him in a co-financing deal on the expensive flop The Cotton Club (1984).

Sign up to our Film Today email

Read more

Evans got his producing career temporarily back on track in the mid-90s, even returning to a deal at Paramount, but suffered a series of strokes in 1998 which restricted dramatically his mobility.

Even this setback could not keep him down, and he returned to the limelight in 2003 to narrate a popular documentary about himself, The Kid Stays in the Picture, which shared its title with his own bestselling 1994 autobiography.

Those words had first come from the mouth of the producer Darryl F Zanuck, who had cast Evans as the bullfighter Pedro Romero in a 1957 adaptation of Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. Ten days before shooting started, Zanuck received a signed petition from the rest of the cast, including Ava Gardnerand Tyrone Power, asking him to remove Evans from the film. It read: “With Robert Evans playing Pedro Romero, The Sun Also Rises will be a disaster.” Zanuck arrived on set and told the assembled cast and crew: “The kid stays in the picture. And anybody who doesn’t like it can quit!”

Evans credited that moment with teaching him to stick to his guns when he became a producer. Of course, we only have his word for what happened, and the autobiography is knowingly hyperbolic, written in the hard-boiled, cornball slang of a dime-store detective novel. When he and MacGraw split, for example, he reports Kissinger telling him: “If I can negotiate with the North Vietnamese, I think I can smooth the way with Ali.” To which Evans replies: “Henry, you know countries, you don’t know women. When it’s over, it’s over.”Advertisement

Some of the book’s stories were later contested, including Evans’s claim that he helped Mario Puzo in 1968 with the “rumpled pages” that eventually became The Godfather. (Puzo claimed not to have met at Evans at that stage.) But then Evans usually had the monopoly on telling his own story. When asked for a comment on him, the Chinatown screenwriter Robert Towne replied: “Why? Why bother? Bob says it all himself.”

He was born Robert J Shapera in New York City – “the J sounding good but standing for nothing I knew of”. His father, Archie Shapera, was a dentist who had a clinic in Harlem, while his mother, Florence, raised Robert and his brother, Charles, and sister, Alice; it was wealth from Florence’s family that accounted for Evans’s privileged upbringing on the city’s Upper West Side.

He was educated at Joan of Arc junior high school, the Bronx high school of science and Haaren high school, and was auditioning for acting roles from the age of 12. (He claimed to have had more than 300 parts on radio as a child.) He put this career on hold and became a disc jockey, a clothing model and a salesman. At 20, he started a successful women’s fashion business, Evan Picone, with his brother.

But acting beckoned him back unexpectedly, when he was approached at a hotel swimming pool by Norma Shearer, who asked him to play her late husband, Irving J Thalberg, in the film Man of a Thousand Faces (1957). He accepted and she coached him obsessively on every aspect of his performance. He also starred in The Fiend Who Walked the West (1958) and The Best of Everything (1959), before his confidence took a knock when he lost out to Warren Beatty for the male lead in The Roman Spring of Mrs Stone (1961).Advertisement

He went back to fashion and made a fortune when Revlon bought his business. He used the windfall to pursue an ambition to become a producer, paying a friend, George Weiser, who worked at Publishers Weekly, to tip him off about any hot literary properties that were about to hit the shelves. Evans had his first decisive success in that field when he snapped up Roderick Thorp’s novel The Detective, which was adapted by 20th Century Fox into a film starring Frank Sinatra. The terms of the option stated that whichever studio bought the rights had to buy Evans as producer also.

He quickly came to the attention of Charles Bludhorn, the head of Paramount’s parent company, Gulf + Western. Evans maintained in his autobiography that Bludhorn had decided to hire him as head of production after reading a New York Times article about him by Peter Bart, though it came to light much later that Bart’s piece had been only a tiny factor in the decision.

In fact, it was Greg Bautzer, Evans’s powerful lawyer, known as “the Kingmaker”, who had convinced Bludhorn to appoint him. “Bobby was a charming guy,” said Albert S Ruddy, one of the producers of The Godfather. “He looked good, with a great tan, and he was down at the Racquet Club all the time hanging around with Greg. [Bautzer] gave Bludhorn a line of bullshit about how this kid knew everyone in Hollywood.”

The industry reacted scornfully to the appointment of Evans, but he silenced the naysayers by turning Paramount’s fortunes around. It was true that he made many bad calls on The Godfather. He was vehemently opposed to the casting of Al Pacino and to the use of Nino Rota’s score. Viewing dailies of Marlon Brando mumbling in the title role, he fumed: “What the fuck’s going on? Are we going to put subtitles on this movie?”

But he helped save the film after the director Francis Ford Coppola turned in an early cut described by Evans as “a long, bad trailer for a really good film”. Though the studio had stipulated a running time of scarcely more than two hours, Evans encouraged the director to make it longer: “I remember lots of wonderful things you shot. They’re not there. Put ’em back.” Bart, whom Evans had hired as his righthand man, observed that “a superbly shot but ineptly put-together film was transformed into a masterpiece”.

Evans showed just as much commitment in making Chinatown. Bludhorn allowed him to co-produce the movie independently while also remaining in his post at the studio, as a sweetener for the prosperity he had brought to Paramount.Advertisement

Though Towne’s neo-noir script was initially incomprehensible, Evans stuck by it in the face of industry advice to the contrary and assigned Roman Polanski to help knock it into shape. The production was stormy. Polanski locked horns on set with the actor Faye Dunaway, and Evans only brokered peace by promising each of them either an Oscar nod for their work on the movie or a luxury car. (Both were nominated.) A Chinatown sequel, The Two Jakes, was almost made in 1985 with Evans in one of the lead roles, until it became obvious that he was not up to the job. It was eventually made in 1990, with Evans producing.

After Chinatown, Evans left Paramount to independently produce such films as Marathon Man (1976), Black Sunday (1977) and Popeye (1980). His career plummeted following the controversy surrounding The Cotton Club (also directed by Coppola).

During the 90s, he produced a handful of movies, including two, Sliver (1993) and Jade (1995), written by the Basic Instinct screenwriter Joe Eszterhas. The lean years, which included a spell in a psychiatric institution, had done nothing to humble Evans or to temper his vulgarity: to show his high regard for Eszterhas’s work, he paid a woman to visit the writer with a note of congratulation concealed in what Eszterhas described as “a certain intimate body part”. It read: “Best first draft I’ve ever read. Love, Evans.”

Evans was nothing if not vain. He professed to be furious when the actor Dustin Hoffman used him as the basis for his portrayal of a crass producer in the Hollywood satire Wag the Dog (1997), though Evans had already inspired another such character, played by Robert Vaughn, in the comedy S.O.B. (1981).

But on those occasions when he facilitated or came into contact with great material, Evans’s determination resulted in some of the most unambiguously brilliant American films of all time. Despite his bluster and brazenness, he had his charms. “Bob was unpretentious and usually said or seemed to say exactly what he thought,” noted Puzo. “He said it the way children tell truths, with a certain innocence that made the harshest criticism or disagreement inoffensive.”

In 2013, Evans published a second volume of memoirs, The Fat Lady Sang. In 2017, the theatre company Complicite mounted a stage adaptation of The Kid Stays in the Picture at the Royal Court in London, with Danny Huston (son of the director – and Chinatown villain – John Huston) as Evans. On the occasion of that production, Evans gave the Guardian his verdict on modern Hollywood. “I’m not into machines. I’m not into Mars. I like feelings. How does it feel? That, to me, is the turn-on. And story. If it ain’t on the page, it ain’t on the screen, or anywhere else.” Reflecting on his life he said: “I like myself. For not selling out. There are people who have bigger homes, bigger boats. I don’t care about that. No one has bigger dreams.”

He is survived by Joshua, his son from his marriage to MacGraw, and a grandson.

• Robert Evans, film producer and actor, born 29 June 1930; died 26 October 2019