Rosamund John was born in 1913 in Tottenham, London. Her films include “First of the Few” in 1942, “The Lamp Still Burns”, “The Gentle Sex”, “Green for Dange” and “When the Bough Breaks” with Patricia Roc. She was long marrried to the Labour MP John Silkin. She died in 1998.

Tom Vallance’s “Independent” obituary:

A grey-eyed honey-blonde, she was one of the most interesting of the well-bred heroines who dominated the British screen of that time. “In those days we were much more ladylike than they are now,” she said recently. “We used to admire ladies in French films because in them actresses were allowed to be real: but English films made us unreal because the audience liked being taken out of the reality of the war.”

Intensely political, she retired into a long and happy marriage to the Labour MP John Silkin and could often be seen attending the House of Commons to hear him speak.

Born Nora Rosamund Jones in Tottenham, north London, in 1913, she was educated at the Tottenham Drapers’ College, then attended the Embassy School of Acting. Her early ambitions were to be an actress or author. After a year in France at the age of 19, she returned to London and was introduced by a former history mistress to the actor-director Milton Rosmer, who cast her in small stage roles and (billed as Rosamund Jones) as a Scots girl in his film The Secret of the Loch (1934), which starred Seymour Hicks as a scientist out to prove the existence of the Loch Ness Monster.

John then worked in repertory, was one of C.B. Cochran’s “young ladies” and at Stratford-upon-Avon did walk-ons and understudied several Shakespearean roles. The actor-producer Robert Donat spotted her there, and cast her as an understudy in his production Red Night (1936). Donat’s biographer Kenneth Barrows recounts that the actor not only had great faith in John’s ability – he was to write in his journals, “One day I shall be proud to say I was one of the first to recognise her great gifts” – but he also fell deeply in love with her and, though he was married, by Christmas 1938 he was writing that John was “the first truly passionate affair of my life”.

When Milton Rosmer directed Donat as Dick Dudgeon in a stage production of Shaw’s The Devil’s Disciple (1940), they cast John as the minister’s wife Judith, but the actress was not yet ready for such an assignment. Though she received good notices during the pre-London tour (“Rosamund John puts into the quiet little wife of the minister an unexpected emotional intensity,” wrote the Yorkshire Post), the London critics were less kind and Shaw himself, attending a matinee three weeks after the opening, wrote Donat a letter bemoaning his “discovery that the minister seemed to have, in Rosamund John, married an escaped lunatic”.

Donat replied, “For the minister’s wife I must take some of the blame. She is a great friend of mine, and it was on my suggestion that she was allowed to tackle the part. She at first gave an extremely subtle, amusing and moving performance as Judith. I am afraid, however, she lacks the technique to sustain the part night after night.

“On the first night, she was inaudible and her frantic efforts the other afternoon were the unfortunate reaction of having read an unending stream of bad press notices, a pretty depressing situation for a young actress’s first appearance in an important part on the West End stage.”

Donat tried to get John the role of Eleanor Eden, his love interest in Carol Reed’s The Young Mr Pitt (1941), but the part went to Phyllis Calvert, who had just had a success in Reed’s film Kipps. John had by now become noted for her strong political views, and had let it be known that she would like to become an MP, prompting Donat to write: “Rather a good description of Johnny at her most independent: Queen Victoria with a school certificate in one hand and the New Statesman and Nation in the other! But a lovely, generous mind, a heart of pure gold, and a body made for the highest pitch of ecstasy.”

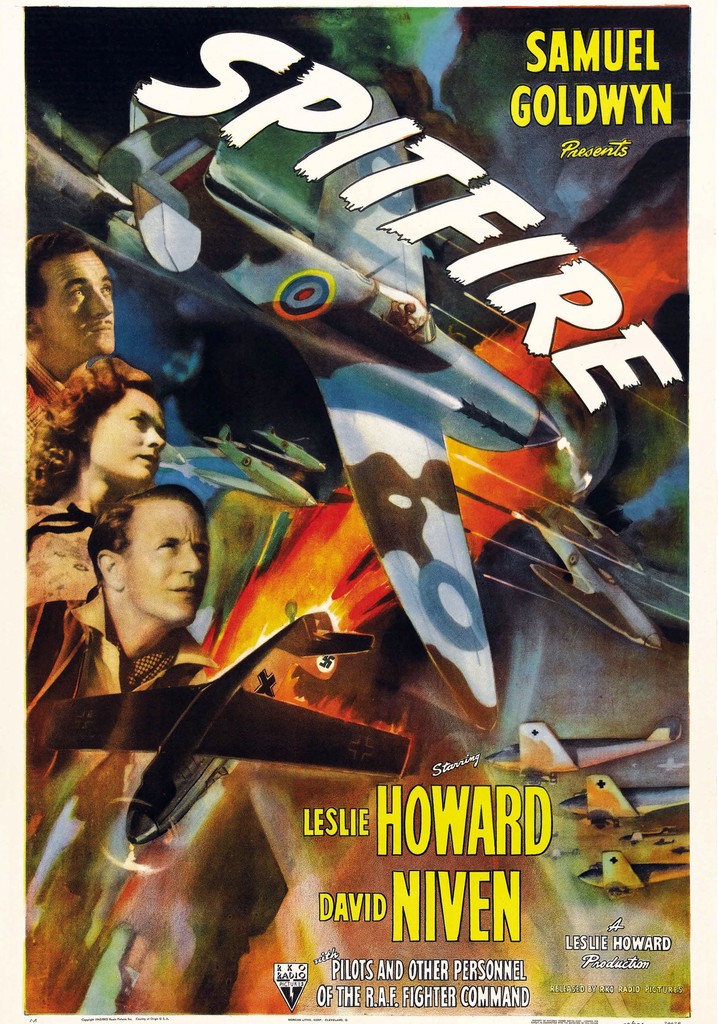

John told the author Brian MacFarlane that her big break came when she was up a tree picking cherries at Donat’s house. “A girl I knew in an agency phoned to say Leslie Howard was looking for someone, and she had suggested me.” After a screen test, Howard gave John a leading role in The First of the Few (1942). As the understanding wife of the Spitfire designer R.J. Mitchell, John projected an extremely English combination of reticence, loyalty and gentle determination, and the film was a big success.

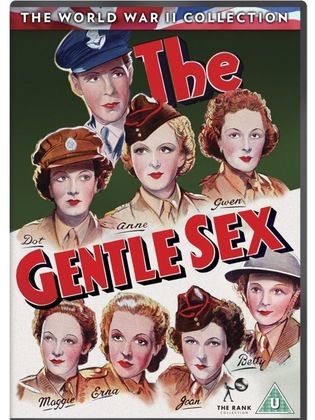

Howard next cast her in another popular wartime piece, The Gentle Sex (1943), as one of seven girls from different walks of life who join the ATS. John wanted to play the cockney girl but was told she “looked all wrong”, despite her pointing out that she grew up in cockney London, and once again she was cast as a Scot (“I used to rush off to John Laurie on another set to help with the dialogue”).

Howard then gave her the starring role in The Lamp Still Burns (1943) as an architect who becomes a nurse and, after initial difficulties adjusting to the discipline, becomes so dedicated that she gives up true love for her vocation. John’s co-star was Stewart Granger, and the pair were so unhappy with the director, Maurice Elvey (“a pompous little man who had made a lot of indifferent films before the war”) that Howard promised to take over the film’s direction when he returned from an urgent trip to Lisbon. The air trip was the fatal one from which Howard never returned.

“Howard taught me everything I knew about film-making,” said John. “He made me realise that the only thing that matters when you are filming is what you are thinking and feeling, because it will show in your eyes.”

In late 1942 John’s relationship with Donat ended bitterly when she told him that she was going to marry Lieutenant Russell Lloyd, but eventually she and Donat made up.

In Bernard Miles’s idiosyncratic comedy Tawny Pipit (1944), filmed in the Cotswolds, John was a nurse who joins a vicar and convalescing pilot to save rare birds nesting near an English village and ensure that they can hatch undisturbed in the middle of a war. “Rank didn’t think they would be able to sell it to America so it was stashed away for a while. When it was shown, it was wildly popular, because it was everything the Americans thought of as being English.”

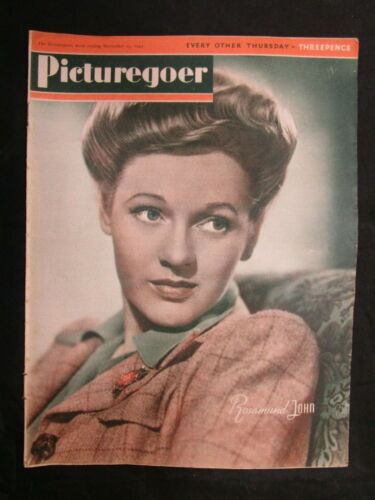

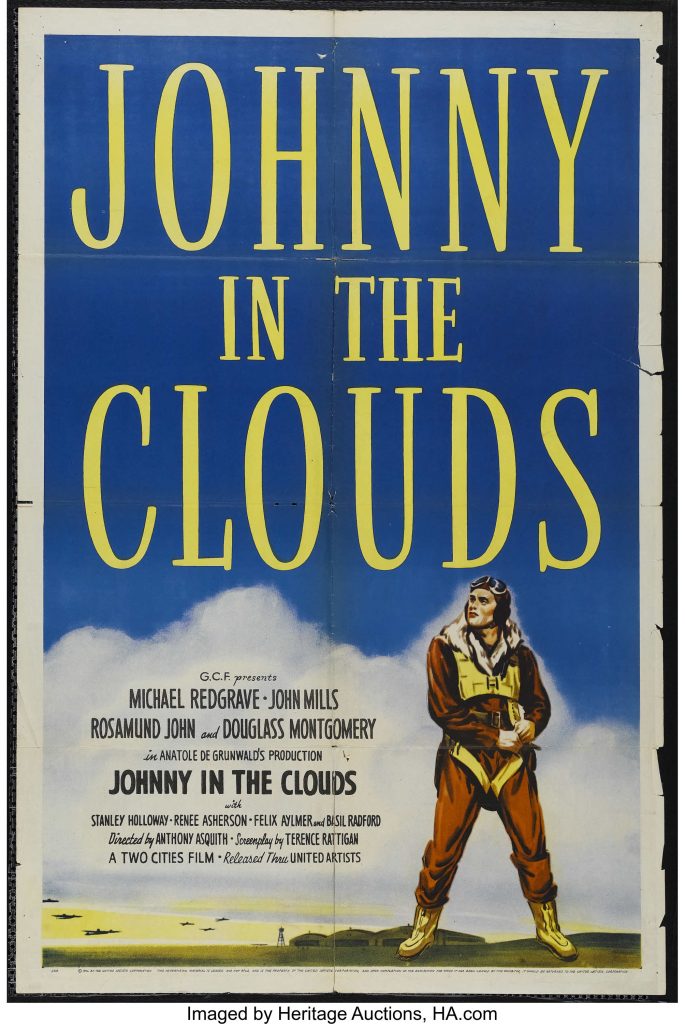

When the fan magazine Picturegoer polled readers for their Gold Medal Awards in 1944, the winner was Margaret Lockwood, but after several American names the next British star on the list was John and her popularity increased even further with her appearance in the outstanding film about a bomber station, The Way to the Stars (1945), written by Terence Rattigan and directed by Anthony Asquith (“my favourite director”). As “Toddy”, the compassionate pub manageress who loses both the flier she marries and the American airman she later befriends, John was the epitome of patrician common sense and stoicism. In a memorable scene, in which she persuades a young pilot (John Mills) that his determination not to marry his sweetheart during the war is misguided, John conveys a wealth of compressed emotion as she tells him: “If I could go back five years now and choose again whether or not to meet David, whether or not to fall in love with him, to marry him and bear his child, I’d choose again to have things happen exactly the way they did before . . . Any other woman in the world would tell you the same.”

The actress welcomed being cast against type in her next film, Sidney Gilliatt’s delightful comedy thriller Green for Danger (1946), in which her character was given a wayward neuroticism, but the movie also marked the end of John’s reign as a major star.

The Upturned Glass (1947), a taut psychological thriller, was stolen by its star and co-producer James Mason, and, though Roy Boulting’s Fame is the Spur (1947) has a subject close to her heart (a radical politician turns out to have feet of clay), it was not a popular success. As the politician’s idealistic wife who becomes a suffragette, John gave one of her best performances (“I enjoyed that film more than any other”) with an immensely touching death scene. The suffragette Christabel Pankhurst was a technical adviser, but not popular with the crew. “God, what a bitch she was,” related John. “The Boultings couldn’t wait to get her off the set.”

A film about the effect of warring parents on a child, No Place for Jennifer (1949), was a big success for the child star Janette Scott, after which John made only one more major film, Street Corner (1953), in which she and Anne Crawford portrayed rather high-toned lady policemen.

John’s final film was a B movie, Operation Murder (1956), but she had long virtually abandoned her acting career for politics and for marriage. In 1949 she became an Equity representative on the Working Party on Film Production Costs, an appointment made by Harold Wilson, then President of the Board of Trade. “It was a great advantage being a woman on that council. All the men around the table were going on about cutting production costs, cutting down wardrobe budgets and so on. I pointed out that one of the reasons people to go the cinema is to see beautifully dressed women, that the money was not being wasted.”

John also served on a committee which established a minimum rate for chorus workers, and with the increasing emergence of television she helped battle with the BBC, which did not want to pay for repeat screenings and wanted to treat actors as self-employed and thus not pay their National Insurance.

It was through her political work that Johns met a handsome young naval officer, John Silkin, 10 years her junior and an intensely ambitious solicitor who had joined the Labour party when only 16. Silkin admitted later that he was first attracted to the film star’s fame, but they ultimately fell in love and were married in 1950, the year that Silkin first contested (unsuccessfully) a Labour seat. He eventually entered the Commons at a by-election in 1963, became a confidant of Wilson and was appointed Chief Whip in 1966. He and John were both vehemently opposed to American involvement in the Vietnam war, and allegedly influenced Wilson’s decision to accede to Lyndon Johnson’s demands for British involvement with only a token “battalion of bagpipers”.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.

Though Silkin always opposed the party’s “hard left”, he and John regarded themselves as precursors of the “soft left” epitomised by Neil Kinnock. Tam Dalyell, who was Richard Crossman’s Parliamentary Private Secretary, was a friend of the Silkins and fondly recalls John’s charm and elegance. Dalyell organised a memorial meeting at Methodist Hall for Crossman and, since it was not a religious service, arranged for poems by Yeats and Byron to be read by John. No one who attended, he said, will ever forget the clarity and resonance of John’s beautiful readings.

The actress maintained her interest in politics to the end, and just 18 months ago attended a Westminster Labour Party brunch.

Tom Vallance

Nora Rosamund Jones (Rosamund John), actress: born London 19 October 1913; married 1950 John Silkin (died 1987; one son); died London 27 October 1998.