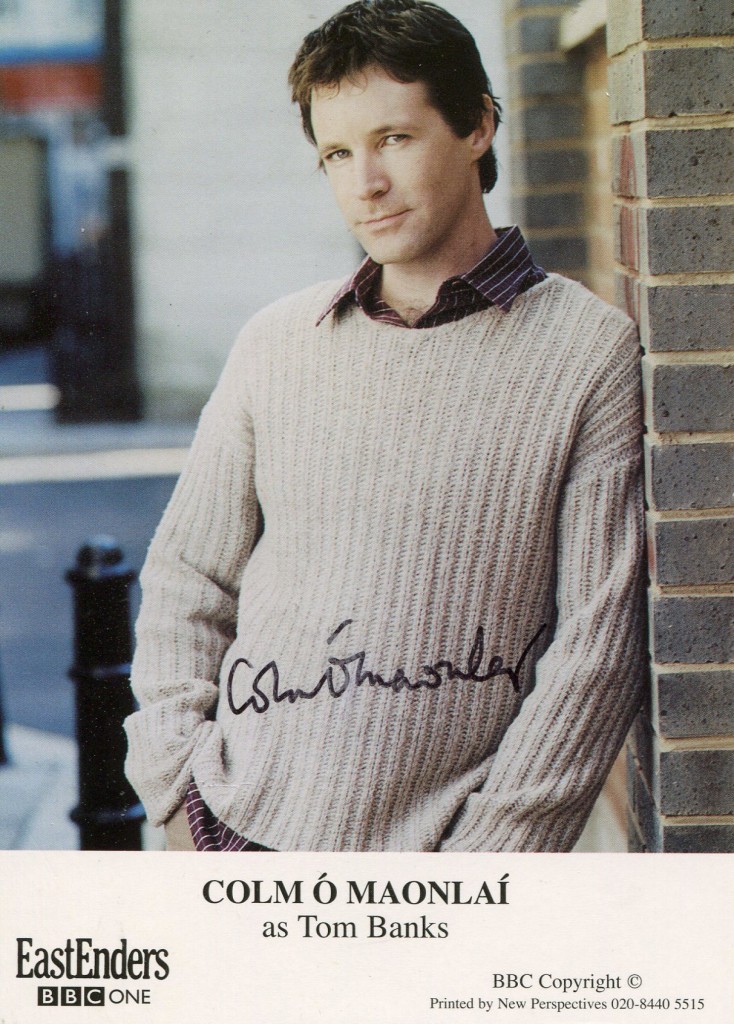

Colm O’Maonli was born in 1966 in Dublin. He is the son of Galway actress Eithne Lydon and the brother of Liam O’Maonli of the muusic group The Hothouse Flowers. Colm made his film debut in 1998 in “Middleton’s Changling”. He has starred in two popular television series, “Eastenders” and “Fair City”. His films include “I Could Read the Sky” and “The Haunting of Hell House”.

Article in “Independent.ie” in 2012:

Once upon a time there were two brothers. Liam was the quiet, talented, focused one. Colm, it seemed, was the playboy, the lazy one, the socialite. Good at looking good, born to live the rock star life, without actually putting out product. And now all of that has changed. Colm O Maonlai has landed a major role in ‘EastEnders’, in which he plays a handsome Irish rogue. Art, it would appear, has imitated life. Victoria Mary Clarke met her old friend.

THE FIRST time I met Colm O Maonlai, he was wearing a wedding dress and red lipstick. And sporting a beard. It was a sensuous summer afternoon, such as can sometimes be experienced in Ireland, and I was at the seaside with some friends.

The sight of Colm in his wedding dress was an arresting one. Not a man you forget easily, this chap. Several things about him attracted me, not least the dress. A sense of fun, an audacity, a willingness to defy convention and be different, be outrageous, be laughed at. Very sad blue eyes, too. Verve and vulnerability.

Later on, he took off the wedding dress and swam naked with his friend; still later he got into bed with one of my friends. Very few women, it would appear, have proved immune to the charming of Colm. Many women that I know have succumbed. I myself have flirted. And yet, in spite of all this, success in the acting business has, until now, eluded him. If ever a man was born to be centre stage this man surely was.

There is, however, a famous older brother. His name is Liam O Maonlai and most of us know him as the lead singer of the Hothouse Flowers, a group who seemed at one point poised to challenge U2 for their position as Ireland’s most popular band. Liam, unlike Colm, is shy and serious and when he’s not on stage, avoids the limelight assiduously. But he’s always been the more famous of the two brothers.

Liam, it appeared, was the creative one, the talented one, the focused one. Colm, it seemed, was the playboy, the lazy one, the socialite. Good at looking good, good at making conversation, good at choosing wines and restaurants. Born to live the rock star life, without actually putting out product. And now, all of that has changed. Colm has landed a major role in EastEnders, a popular soap opera with millions of viewers. He plays a loveable, handsome Irish rogue, a ladykiller who beds women. Art, it would appear, has imitated life.

The Hothouse Flowers, meanwhile, no longer tour the world, playing to stadium crowds. Colm has, he says, stuck it out for 10 years and success has naturally arrived.

The last time we met, last December, it was Colm’s birthday. He was utterly broke and very depressed. I bought him a bottle of turquoise aura enhancer, to unblock his throat chakra. He didn’t have the price of a pint, but we agreed that he would round up the bus fare that night, and we would go for a drink. He had, he said, despaired of ever getting work and was seldom going out. But it was his birthday.

Sitting here now, in Borehamwood, just down the road from Elstree Studios, he samples several different wines, before choosing an appropriate one for the meal. And he sports a snappy overcoat and a Grecian tan. But he does not forget that all of this could be taken away in an instant. And he remembers how devastating it was to be unemployed.

“I was absolutely at the end of my tether,” he says, about that birthday. “I was emotionally, physically and mentally drained. There was nobody in the house except me, and I took my bed down to the sitting room and spent two months lying there. Waking up, turning on the television and lying there and only going out to buy food. Nursing my ego. Eventually, I snapped out of it. The sun was shining that day.”

Colm is a man of many contradictions. And, he admits, many demons. Most of whom he will not confront. Not yet. Acting, he says, is a way to hide. And a way to focus. Now that he is working full-time, he couldn’t be happier. There isn’t time for self-examination.

When he asked me if I would like to interview him, he suggested that he was willing to talk candidly about his personal life. Now that I am here, he says, the thought disturbs him.

I ask him if he ever wonders about the meaning of life, about what, if anything, dictates what hand we will be dealt.

“I can’t even go for a massage because of the fear that I might discover something that I don’t want to. I’m not in any rush to get down to the nitty gritty!”

But, I insist, sometime you’ll have to.

“Most people don’t. There is no answer.”

You don’t believe people are born with a purpose? I say.

“No. And I’m a lazy person.”

Are you?

“You know I am. I am terribly lazy.”

But you were born to be rich and famous, I say, because you took so naturally to that lifestyle.

“I have no idea where that comes from. But it makes life easier.”

You didn’t want to work hard and make money, become an investment banker?

“I was shit at school. I had no interest in school, only in sports. Hurling and football and tennis and basketball, table tennis, snooker, every sport I am well into. Long distance running. But I started smoking when I was 13 and that put paid to that.”

How about music? – his father was an engineer who sang and according to Colm he had such a beautiful voice it made him weep.

“I play the whistle, and the bodhran. It seems to me that I’ve got talents, but I don’t know what to do with them. I was always too afraid to make a mistake. Look at Liam, he’s completely open to the music, that’s his life. He’ll take his whistle out on the train, and he doesn’t give a shit.”

You are more sensitive to what people say and think about you?

“Yes. Absolutely.”

Have you been overshadowed by Liam?

He pauses. “I suppose I have been overshadowed. How’s it going? Hey, how’s Liam? You just have to deal with that and I have dealt with it. I’ve found my own niche and it’s got nothing to do with music. I couldn’t be competitive with Liam.”

Why not?

“I would kill him! It’s a great chance for me, being here, to get rid of that stigma. Now I’m here I can be a great actor!”

From the very beginning of his life, Colm took the jester’s role, while Liam played the straight man.

“My earliest memory is of Liam walking me up and down the stairs, I was about one-and-a-half. We were walking down and we got to the second step and he let go, thinking that I was OK, and I fell over and fell right down to the bottom, hit my head off the wall and started laughing.”

That could be a metaphor for your life.

The brothers were brought up in a deeply religious family, who spoke Irish and went to Mass.

“Nine months and a day after my parents got married, Liam was born. And I suppose my parents thought, ‘Oh, we could do this again.'” And they did. My father’s parents were very religious, they went to Mass twice a day. And two of his sisters are nuns and his brother is a priest. Out of the four of them.”

Colm may not have embraced religion, but he does love to speak Irish.

“It’s a hugely important part of my life. My father was taught by his father and his father was very patriotic. He served in the IRA. And he was a very hard man, very hard. We grew up speaking Irish. If I’m around Irish people, I think in Irish. It’s a different rhythm, different attitude, different emotions. It’s amazing, if you are speaking Irish, you almost have to be poetic!”

The first play that Colm acted in was Fiche Bliain ag Fas, at the Abbey, when he was 13.

“I loved it. And I thought why would I want to go to school, when I can do this?”

I suggest that he practises acting in his daily life, on a regular basis. Charming the ladies, for example.

“That’s something I learned in Kerry, actually. I was caught fiddling with the maid and I talked my way out of it. Layers. I probably have quite a few layers.”

Sagittarians, I say, are known for being direct.

“I’m an actor. I probably learned it as a device to put up with shit growing up. Everyone has hassles growing up and you just devise strategies to deal with them. Let’s just say that mine wasn’t the easiest of growing-ups. But I won’t talk about that. That will be a book. I’ll have to kill everyone off first! I’ve got nothing to say. I don’t like whitebait.”

Has wanting to be an actor got something to do with wanting to be approved of, and liked, I ask. Is there an element of vanity involved? And attention-seeking? He pauses again.

“Yeah, there is.”

The first time I met you, you were wearing a dress and lipstick, I remind him.

“Oh yeah, why not? Wear a dress, wear some lipstick, especially with a beard.”

On another occasion, Colm insisted on joining me for dinner with Van Morrison, with his lipstick on.

Why the wedding dress and the lipstick?

“It wasn’t a wedding dress, it was a bridesmaid’s dress. They were mad times, actually.”

You were a bit wild. You don’t seem so mad now.

“I had nothing to focus on.”

Except going out, every night.

“I couldn’t have done that, I didn’t have any money.”

No, but you always met people who did.

“I was not a sponger! I was entertaining, so people bought me drinks. I went down to Slogadh once and I had eight pence in my pocket, so I decided to knock pints back in one go, as a way of getting people to buy me drinks and I got eight pints before I knew it.”

Was that just a way of getting attention?

“Maybe. It does work. But I think at 35 it’s time to decide what to do with my life. Get into the pot belly and forget about how I look. Get it together and stop messing.”

Would you like to be very famous?

“I don’t know.”

If I was a Hollywood producer and I said I will make you a big star?

“I would think it would depend on the part. Fame is useless, by itself. You have to be working. That’s why I feel really sad about these Big Brother people. These people have no idea what they are letting themselves in for.”

You have become a little bit famous.

“Yes. But it’s been great. People say ‘hello’ and smile, which is a lovely thing. It’s hilarious really, to have gone from nothing to this. I was as prepared as you can be, for being recognised, because of hanging out with Liam. And, of course, Bono and me are good mates!”

People used to mistake you for Liam.

“Yes, at one stage I got really freaked out. People would come up and say ‘Can I have your autograph?’ I would say ‘Why?’ And in the end it was easier to just do it, rather then explain that I was a different person.”

But in Ireland you were already known.

“Just from a couple of ads. I met this guy in Greece, he tapped me on the shoulder and said, ‘Excuse me, you’re from that butter ad.’ I said don’t talk to me about that butter ad, God almighty! And then he said ‘You’re in EastEnders as well!’ Sometimes when you are in a bad mood, to get a letter from a fan, to know that there’s somebody out there who thinks you are doing a good job is great. I have no problem with being recognised.”

Are you seeing somebody at the moment?

“Yes I am. Her name is Fiona. She’s like a rock you find in the sea when you go on holidays and she’s always there to go back to. She’s not a famous actress. No, never again!”

What do you mean, did you go out with a famous actress?

“No. Or did I? Maybe I did. It’s a possibility.” Colm has had relationships with several high-profile women, but this is something that he doesn’t want to talk about. He says it wouldn’t be fair.

You have a reputation for being something of a Casanova, I say. He laughs.

“You don’t think that’s why I got this part? Ah, no, I’m getting bored with that, with being stereotyped as a womaniser.”

But you certainly were a womaniser.

“I like women!” He thinks about this and looks serious, for a moment. “I don’t think I do actually like women. I need them. But I don’t like them.”

When did you first fall in love?

“With you! Ha ha. No, I was 11 when I first had my heart broken. Down in Kerry. This woman just came out of nowhere and she was absolutely beautiful, dark hair, sallow skin. I’m really into sallow skin.”

Does your mother have sallow skin?

“No. It doesn’t always have anything to do with your mother! Anyway I’m not going to talk about my mother. So many times, I wanted to say to this girl ‘I love you, I’m madly in love with you.’ And I never did. And I wrote to her and never got a reply and I was absolutely devastated. I was absolutely besotted and we got on really well. Maybe she was just not into me. Maybe she didn’t like boys. I was very, very let down, I wrote to her when I got home. I said, ‘Please write to me and tell me that you are still alive.’ And that scared her off completely.”

Do you know her name? “I shut it out, it was too much to bear. Every time I was with her, I was overwhelmed. Obviously, she couldn’t give a shit. And that’s why every letter I get from a fan, I will always write back.”

Colm may not like women, but one senses that he will be kinder to them in future, now that he can get paid to be roguish on television. He may even plumb the depths of his soul for more demanding roles when he leaves EastEnders.

Or he may not. He does not like to have his soul disturbed and he didn’t like my questions. “I’m never doing another interview again,” he assures me, as we get up to leave. “Never.”

The abovr “Independent.ie” article can also be accessed online here.