It is surprising and disappointing that Ann Sheridan is not better known today. In her prime years in the 1940’s she was one of Warner Brothers most famous leading ladies on the same pedestal as Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. Her career is in urgent need of positive reappraisal. She was born in 1915 in Texas. She made her film debut in 1934 in “Search for Beauty”. Her more famous movies include “Angels With Dirty Faces” with James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart in 1938, “Dodge City” opposite Errol Flynn, “King’s Row”, “Nora Pre ntiss” and “The Unfaithful”. She was starring in the television series “Pistols’n Petticoats” when she became ill and died in 1967 at the age of 52.

TCM overview:

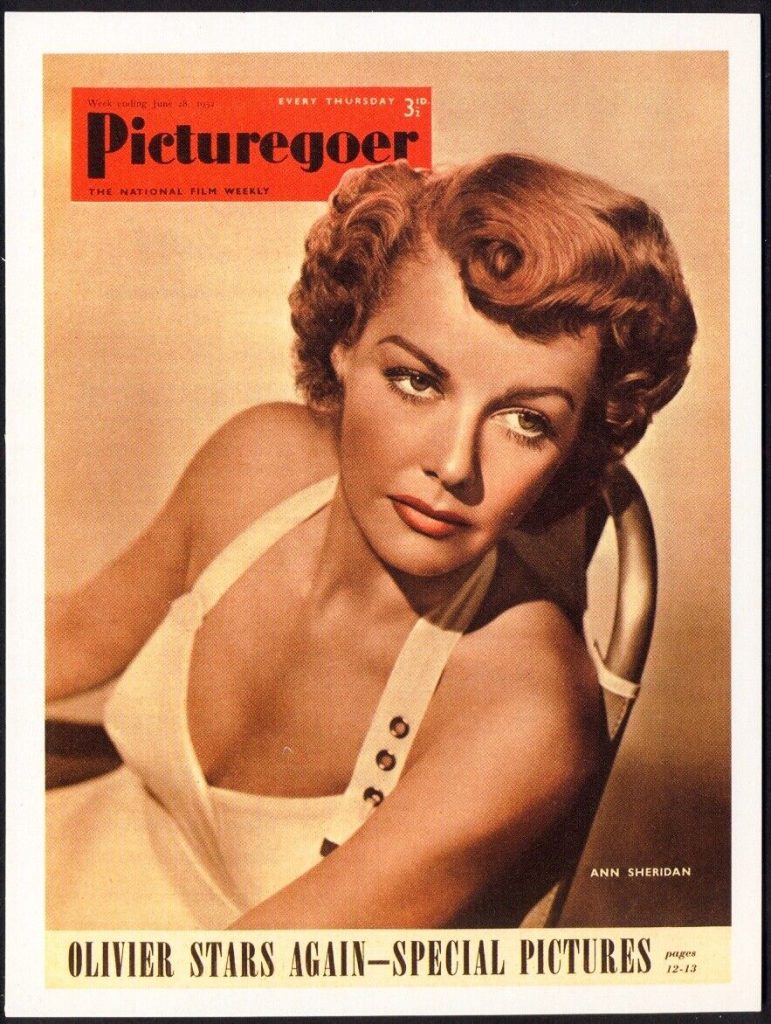

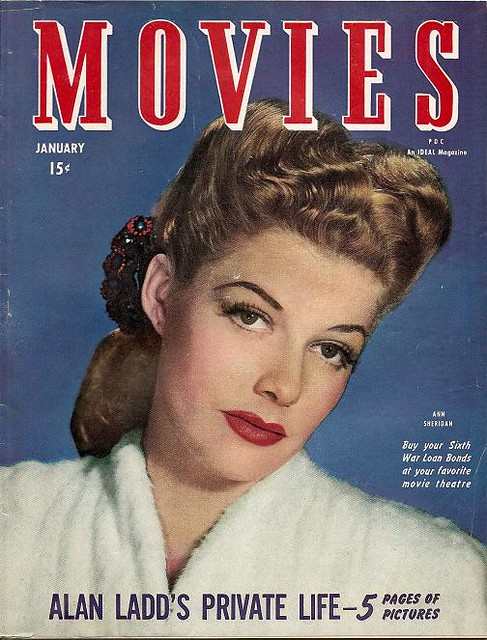

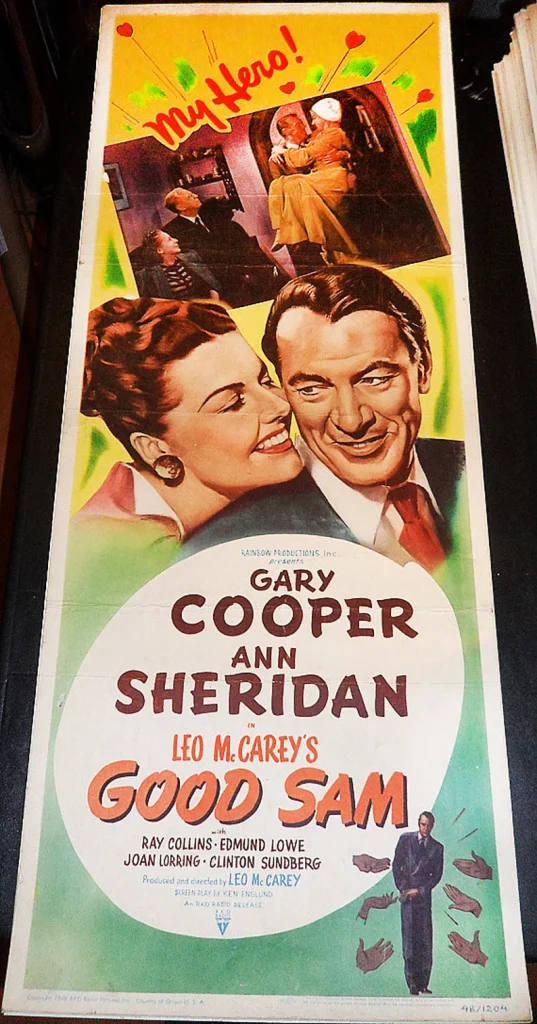

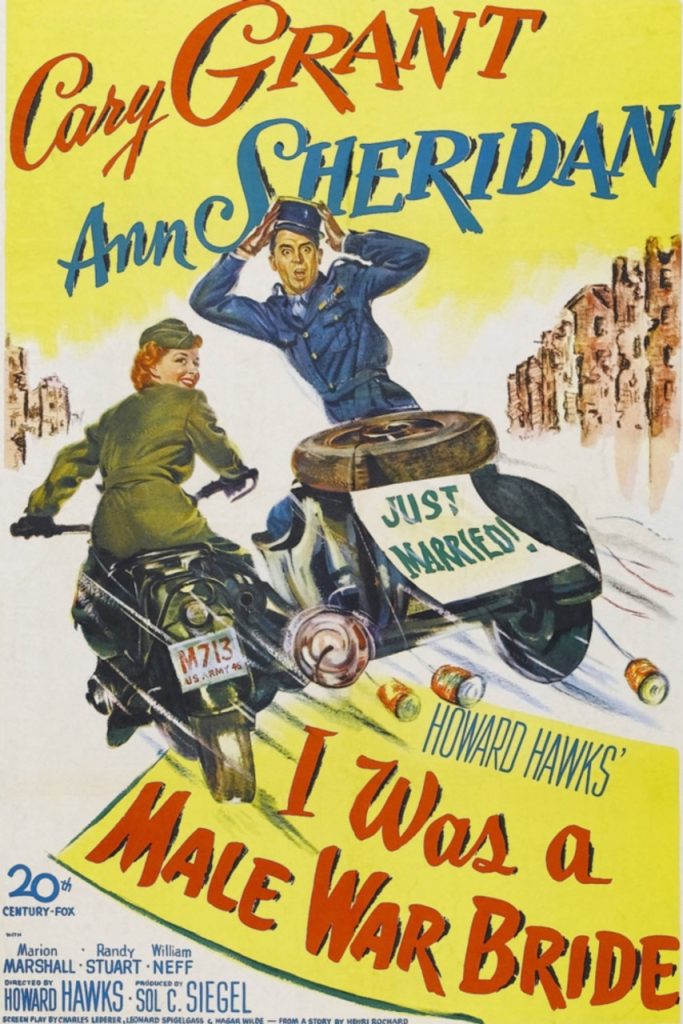

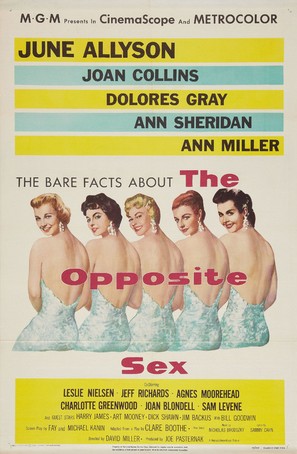

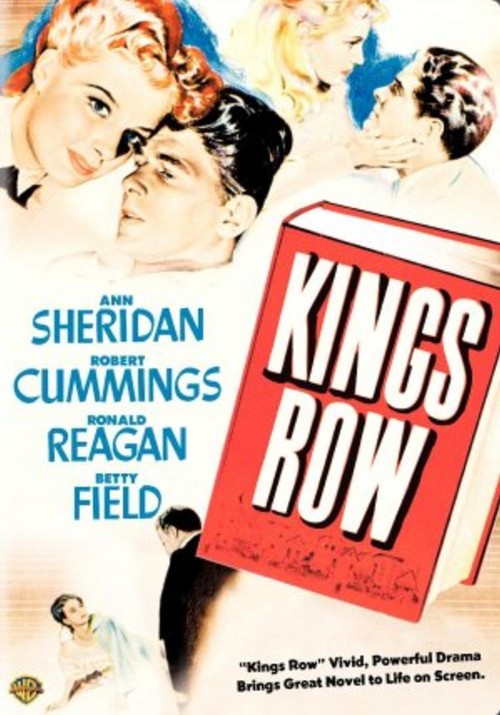

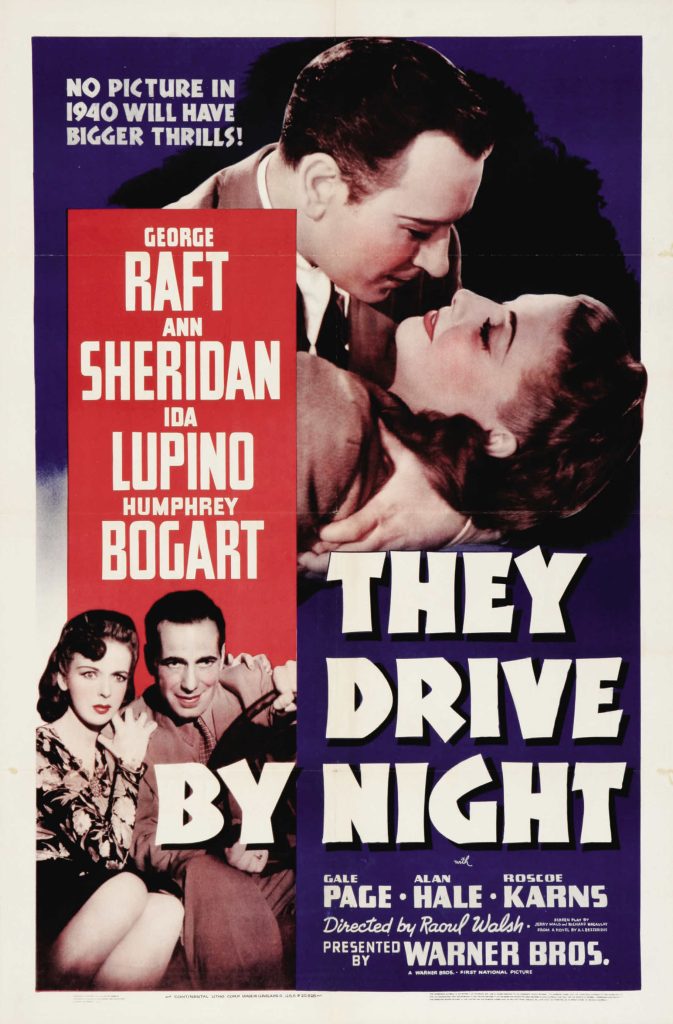

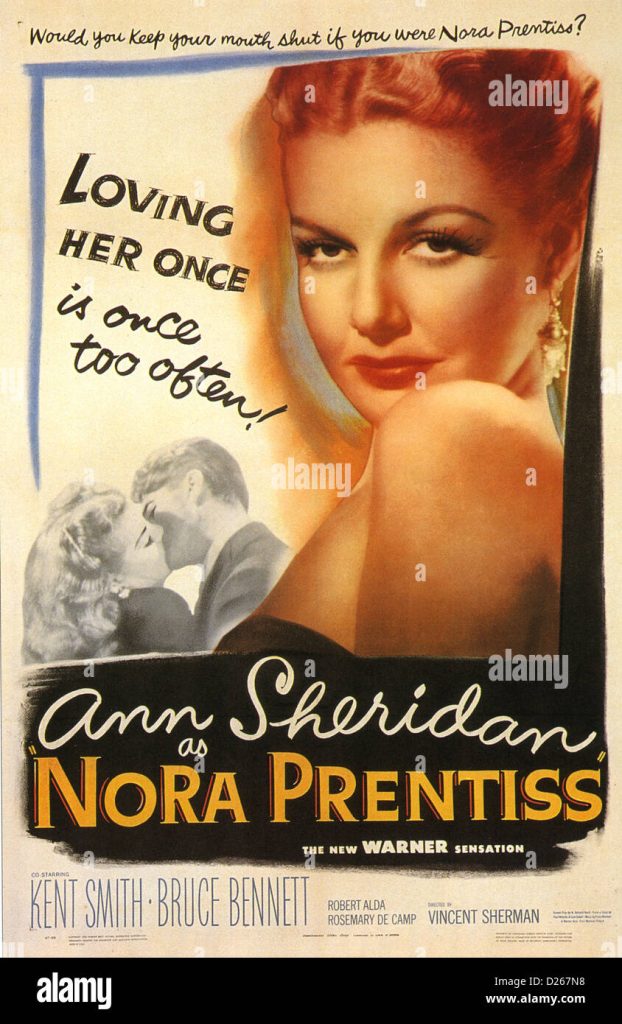

She was Warner Brothers’ “Oomph Girl” and a popular WWII pin-up but Ann Sheridan fought to be taken seriously in Hollywood. After a fruitless start at Paramount, the ravishing redhead allowed the Warners publicity mill to make her an overnight sensation, channeling the buzz to barter for better roles. She enjoyed name-above-the-title status for “It All Came True” (1940), in a role rejected by Bette Davis, then teamed with Davis for the screwball classic “The Man Who Came to Dinner” (1942), and more than held her own opposite studio mates George Raft and Humphrey Bogart in “They Drive By Night” (1940). It was as the small town heroine of “King’s Row” (1942) opposite Ronald Reagan, that Sheridan became a bone fide star, but her tenure at Warners was punctuated by suspensions for turning down roles. Prior to breaking with the studio in 1948, she scored as a Frisco chanteuse who compels doctor Kent Smith to fake his own death in the noir sleeper “Nora Prentiss” (1947). As a free agent, Sheridan enjoyed one of her better roles opposite Cary Grant in “I Was a Male War Bride” (1949) but a downturn in her industry stock drove the aging actress to television. She capped her 30-year career as the star of the CBS western sitcom “Pistols ‘n’ Petticoats” (1966-67) but was felled by cancer before the end of the first season. Gone at 51, Ann Sheridan escaped in death the humiliating career twilights of aging rivals Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, remaining in the eyes of movie lovers a quick-witted comedienne and a sensuous dramatic actress rolled into one unforgettable package.

Ann Sheridan was born Clara Lou Sheridan in Denton, TX on Feb. 21, 1915. The last of five surviving children born to George W. Sheridan, a garage mechanic and direct descendant of Union general Philip Henry Sheridan, and the former Lula Stewart Warren, Sheridan grew up a tomboy, riding horses, playing touch football, and standing up to bully boys twice her size. After completing her primary education at Robert E. Lee Grade School and Denton Junior High School, she enrolled in North Texas State Teachers College with a mind toward studying art. Growing frustrated with the disciplines required of fine art, Sheridan drifted towards campus dramatics and participated in the school band, dreaming of traveling to New York City to become a Broadway chorus dancer. In 1932, Sheridan’s older sister Kitty enrolled the 17-year-old in a national contest sponsored by Paramount Pictures in Hollywood as publicity for the upcoming film “Search for Beauty” (1934). Sheridan was one of 30 finalists invited to Hollywood for the privilege of a screen test.

Despite pudgy cheeks, unmanageable hair, and a gap-tooth smile, Sheridan was offered a six-month contract with Paramount, earning a then-admirable $50 a week. After her 10-second bit as a pageant contestant in “Search for Beauty,” Sheridan was given little to do on the Paramount backlot, apart from taking drama lessons from the studio’s resident coach Nina Mousie, and appearing in plays staged for the exclusive pleasure of the studio front office. While appearing as a character named Ann in the Harry Clork-Lynn Root comedy “The Milky Way,” Sheridan was advised by her handlers at Paramount to change her name so that it might fit more comfortably on a marquee. Adopting her character’s name, Clara Lou Sheridan became Ann Sheridan. A friendship with director Mitchell Leisen led to a featured role, as a stenographer driven by snobbery to suicide, in “Behold My Wife!” (1934), which allowed the young hopeful to break from the purgatory of extra work and doubling that her been her lot as a Paramount contract player.

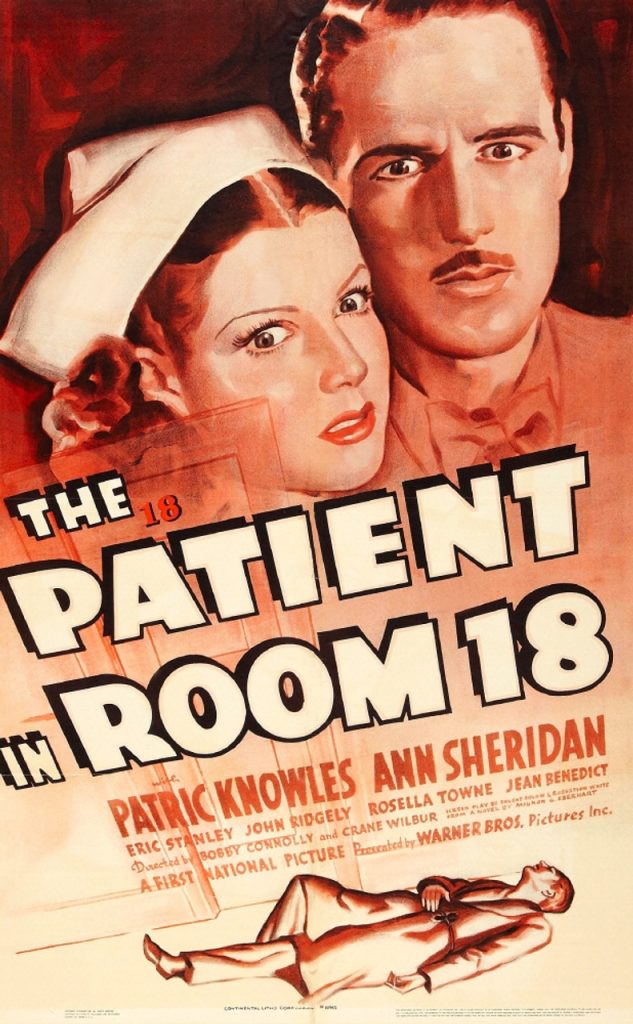

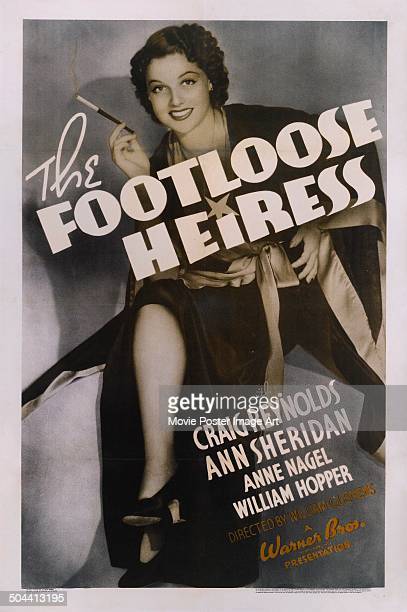

Sheridan enjoyed her first lead role in Charles Barton’s “Car 99” (1935), as rookie cop Fred MacMurray’s telephone operator girlfriend. She was paired with cowboy star Randolph Scott for Barton’s “Rocky Mountain Mystery” (1935) but was bumped back to bits, playing a nurse who bandages George Raft in “The Glass Key” (1935) and a Saracen slave in Cecil B. DeMille’s “The Crusades” (1935). While she was on loan to Ambassador Pictures for “Red Blood of Courage” (1935), Paramount dropped Sheridan’s option. She made one film for Universal, playing a spoiled rich girl who flirts with campus radicalism in Hamilton McFadden’s college comedy “Fighting Youth” (1935), before finding her way to Warner Brothers, her home base until 1948. Though her scenes were cut from Ray Enright’s musical comedy “Sing Me a Love Song” (1936), she found work in Warners’ steady output of crime films, appearing in prominent roles in Archie Mayo’s “Black Legion” (1937), Lloyd Bacon’s “San Quentin” (1937) and Michael Curtiz’s “Angels with Dirty Faces” (1938) alongside fellow contract player Humphrey Bogart. Between 1936 and 1938, Sheridan was married to B-movie actor Edward Norris.

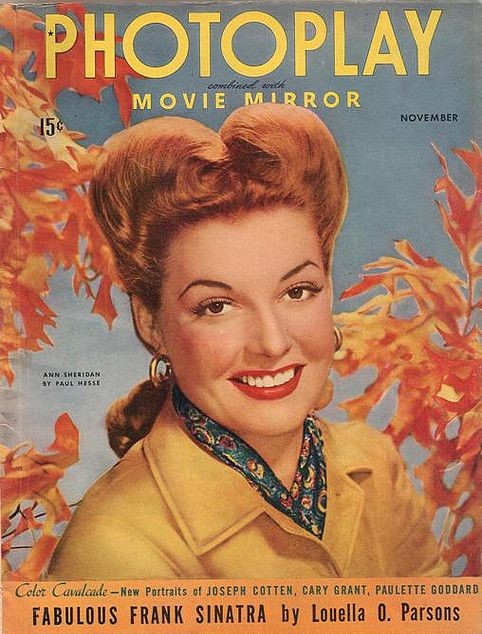

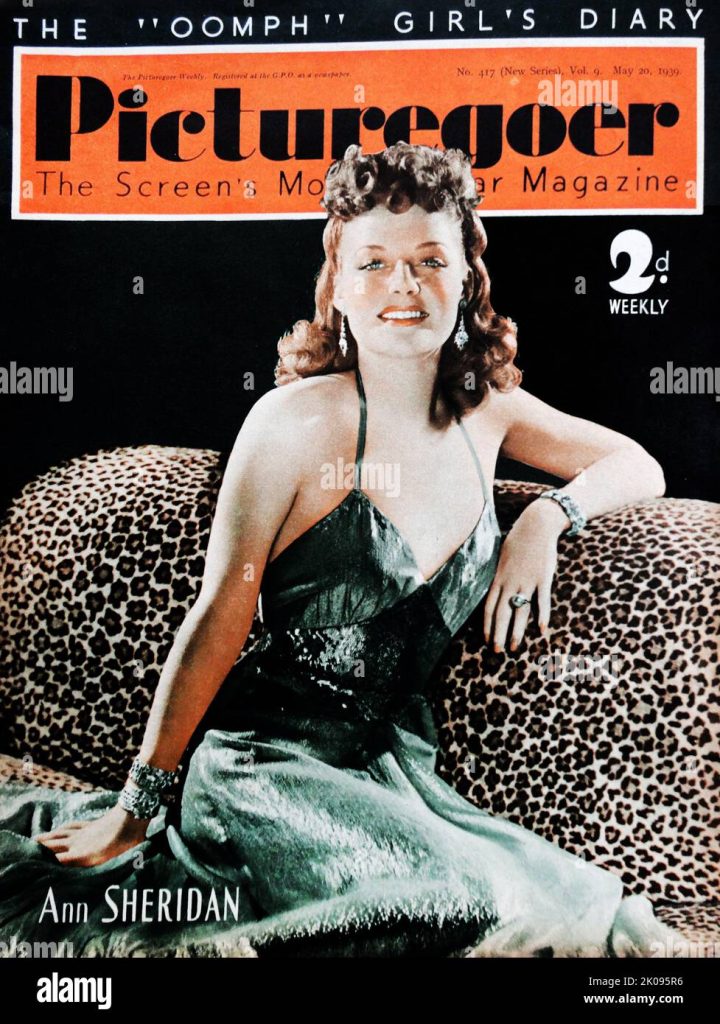

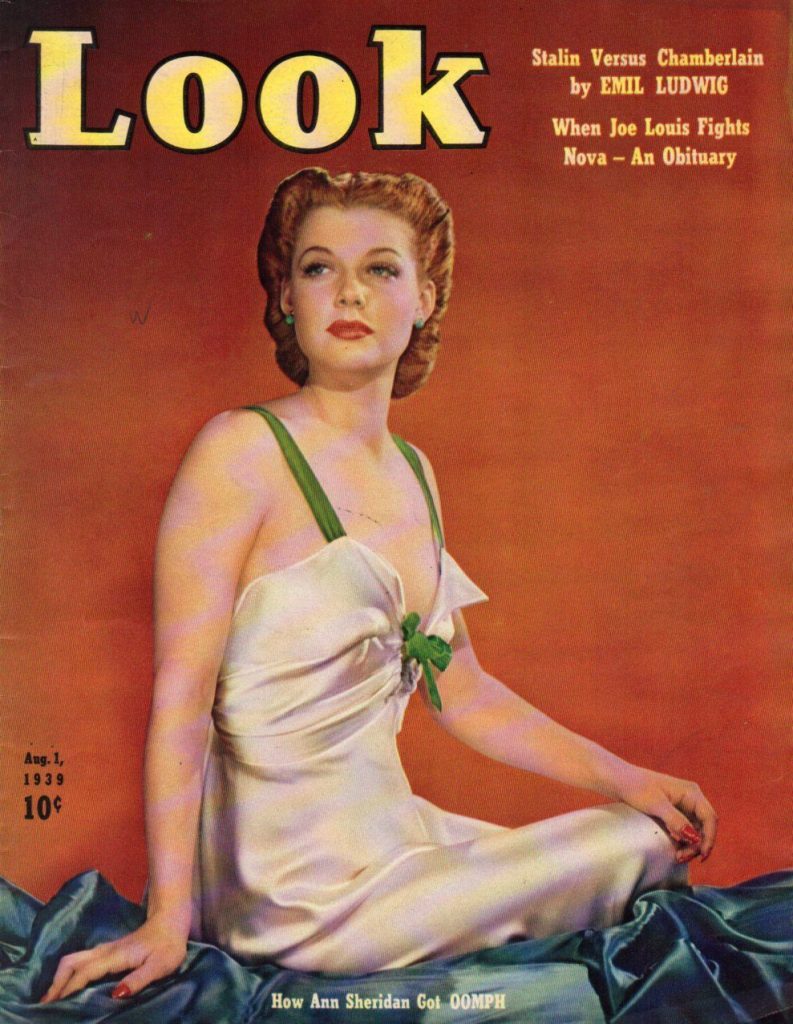

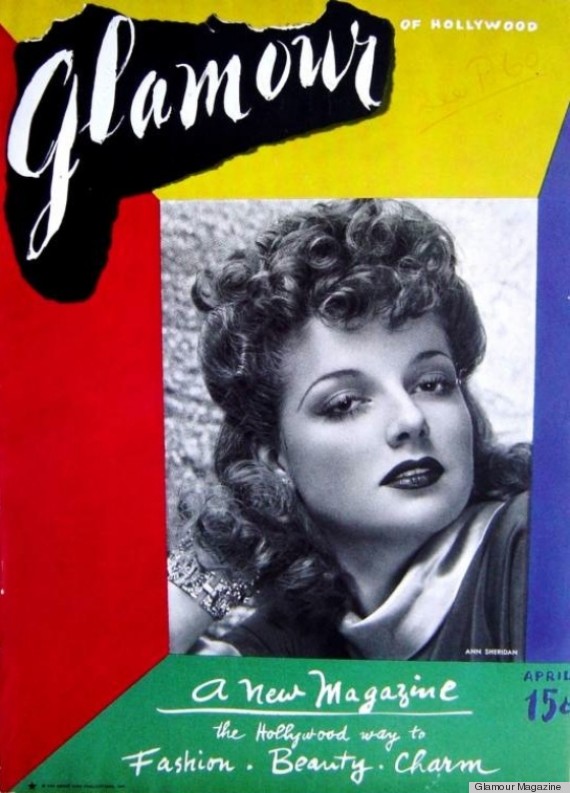

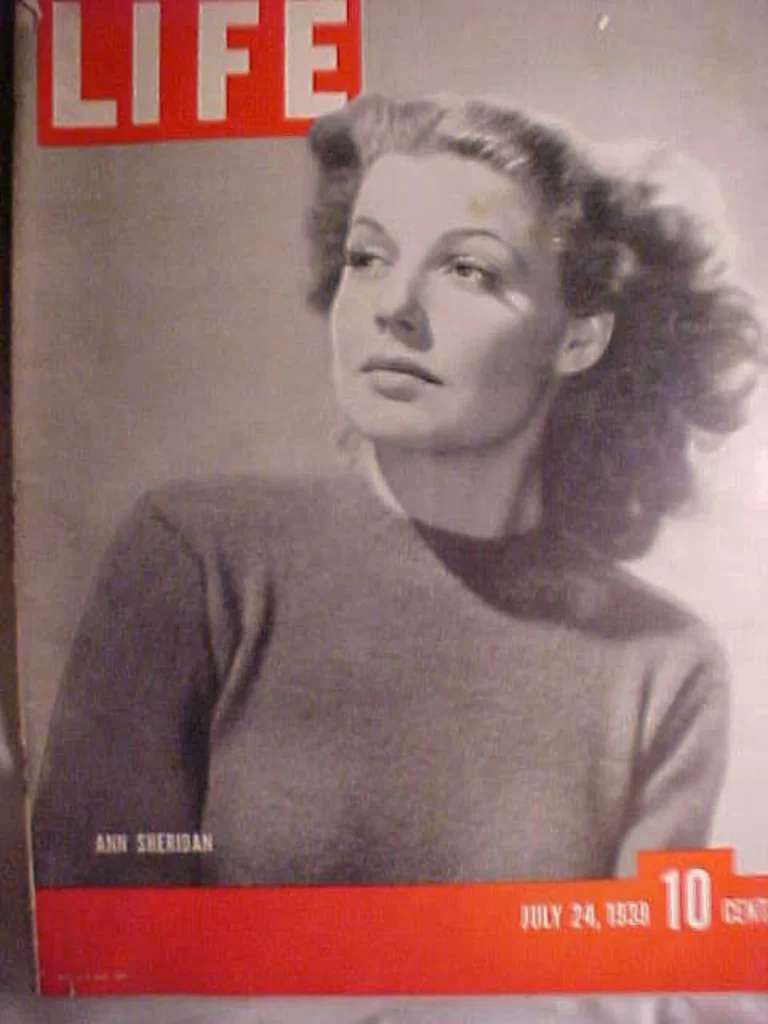

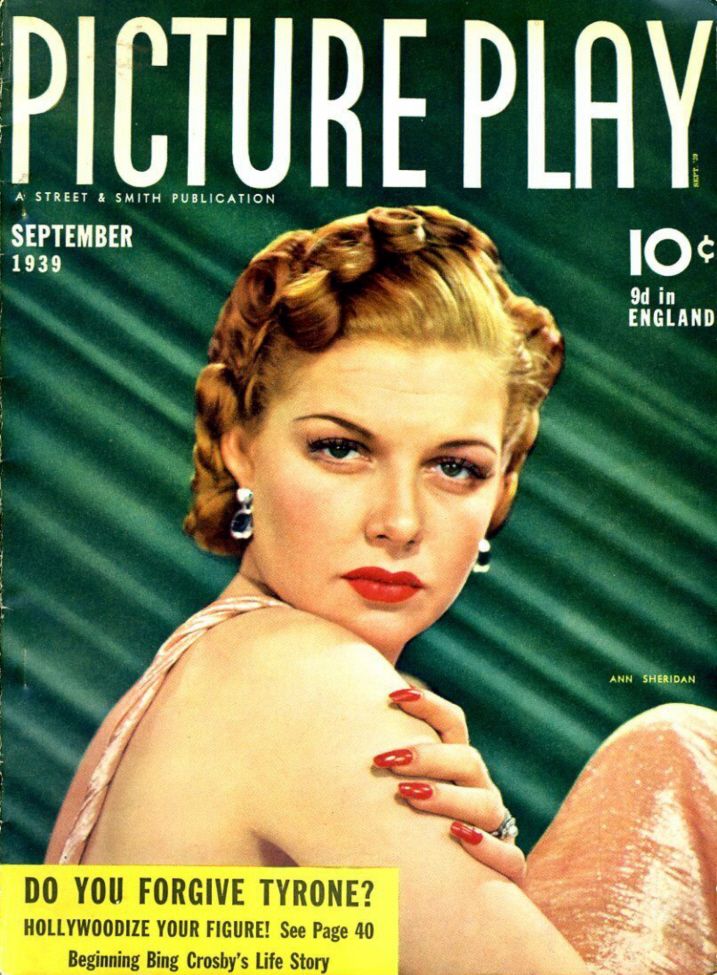

In 1939, Sheridan became the focus of an unusual Warners publicity stunt, inspired by a comment made by gossip columnist Walter Winchell that Sheridan, as gangster James Cagney’s social worker girlfriend in “Angels with Dirty Faces,” had “umph.” Recoining the phrase slightly, the studio assembled a team of 13 judges – including choreography Busby Berkeley, designer Orry-Kelly, photographer George Hurrell, producer-director Earl Carroll, and bandleader-actor Rudy Vallee – charged with naming “America’s Oomph Girl.” Following a highly-publicized but patently rigged competition, Sheridan was awarded the honor, beating out (so the Warners publicity mill had moviegoers believing) Alice Faye, Carole Lombard, Hedy Lamarr and Marlene Dietrich. Hurrell’s elegant portraits of the titian-tressed actress helped put Sheridan across to the public, creating curiosity and sensation where there had once been disinterest. As a result, Sheridan would soon become one of the most popular pin-ups of the Forties, but she always derided her nickname as the sound an old man makes when bending over to tie his shoes.

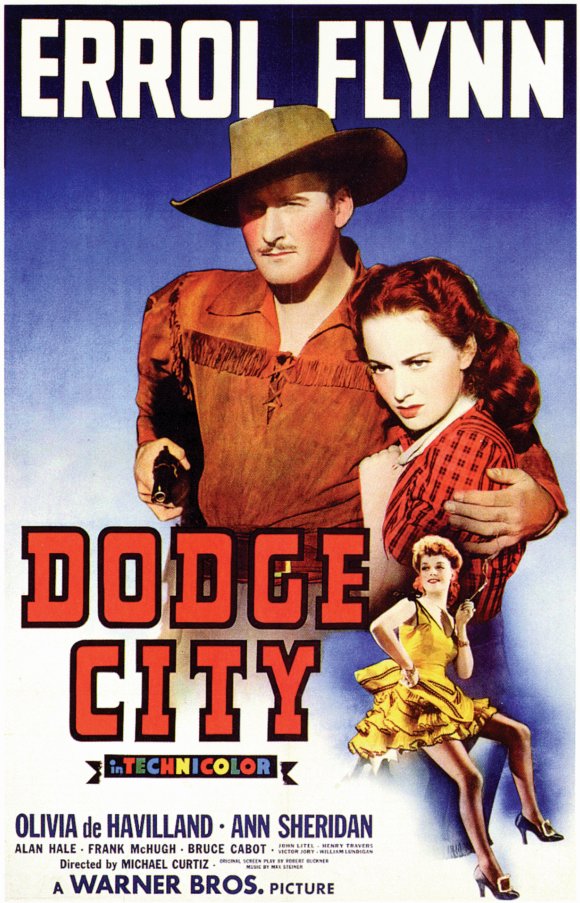

Interest in Sheridan’s crowning as the Oomph Girl had a retroactive effect on several movies in which she had already appeared. Though she played small roles in both, Sheridan received preferential placement on the posters for Busby Berkeley’s “They Made Me a Criminal” (1939) and Michael Curtiz’s Errol Flynn starrer “Dodge City” (1939). Ill at ease at having achieved success through crass studio duplicity, Sheridan was given a backlot pep talk by actor Paul Muni, who advised her to use the exposure from the stunt for the betterment of her career. She was selected by producer Mark Hellinger to star in Lewis Seiler’s “It All Came True” (1940), a role turned down by Bette Davis. Cast as a down-at-heel nightclub singer given a second chance at stardom when mobster Humphrey Bogart turns her boarding house into a nightclub, Sheridan charmed audiences and sang two songs. Now boasting name recognition with moviegoers, Sheridan enjoyed an elevated status in her subsequent film assignments and was, like teen starlets Bonita Granville and Deanna Durbin, made the heroine sleuth of her own mystery novel, marketed by the Whitman Publishing Company for young readers.

Cast again opposite George Raft and Humphrey Bogart in Raoul Walsh’s “They Drive By Night” (1940), Sheridan played the good girl to Ida Lupino’s bad egg. On the lighter side, she donned furs and jewels to play a conniving actress in William Keighley’s “The Man Who Came to Dinner” (1942), winding up packed inside a mummy’s case for her troubles and shipped to Nova Scotia, and teamed with Jack Benny for Keighley’s “George Washington Slept Here” (1942), with the pair cast as city dwellers who buy a tumbledown Pennsylvania farm house. Sheridan enjoyed top billing as the tomboy heroine of Sam Wood’s “King’s Row” (1942), an adaptation of the 1940 novel by Harry Bellaman, which made a star of Sheridan’s fellow Warners contract player Ronald Reagan. Though the studio publicity department announced Sheridan and Reagan as the proposed stars of the upcoming “Casablanca” (1942), the actors were never seriously considered for the roles that went ultimately to Ingrid Berman and Humphrey Bogart.

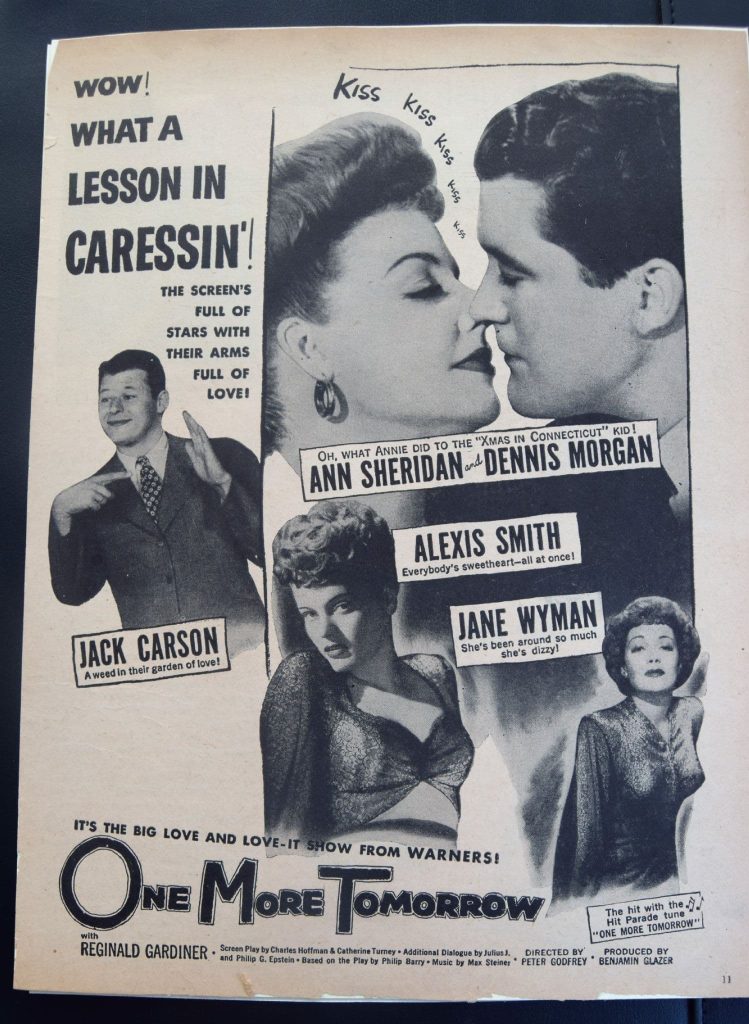

In 1942, Sheridan married actor George Brent, her co-star in Lloyd Bacon’s “Honeymoon for Three” (1941), a union that lasted just one year. The actress’ star turn in “Shine on Harvest Moon” (1944), a biopic of vaudeville singer Nora Bayes, was pitched by Warners as “Sheridandy” though the actress loathed the picture, eager to expand into edgier material and more demanding roles. Placed on suspension for refusing assignments after the troubled production of “One More Tomorrow” (1946), Sheridan sat out most of 1946 before a writer’s strike and the looming expiration of her Warners contract left her with bargaining leverage. The result was a six-picture deal for which Sheridan was given script approval and enjoyed an uptake in her asking price. The first film out of the gate under these new terms was Vincent Sherman’s “Nora Prentiss” (1947), a noir-flavored woman’s picture recounting the tragic love affair of Sheridan’s slinky nightclub singer and Kent Smith’s guilt-wracked surgeon, who fakes his own death as the start of an ill-advised midlife do-over.

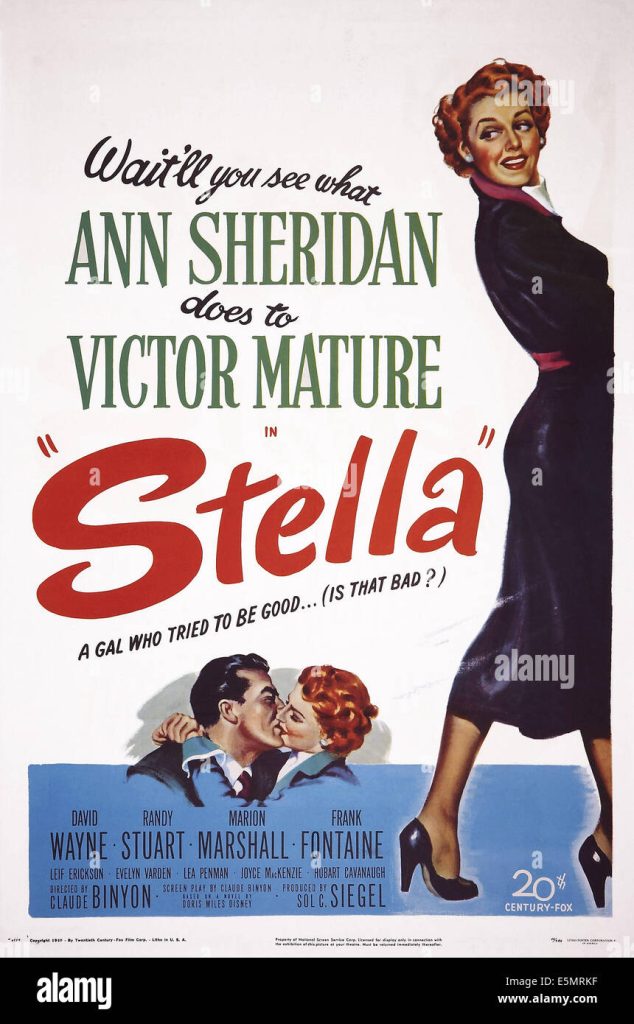

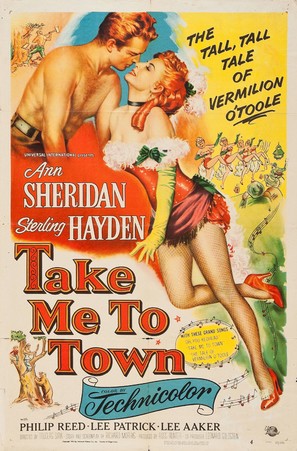

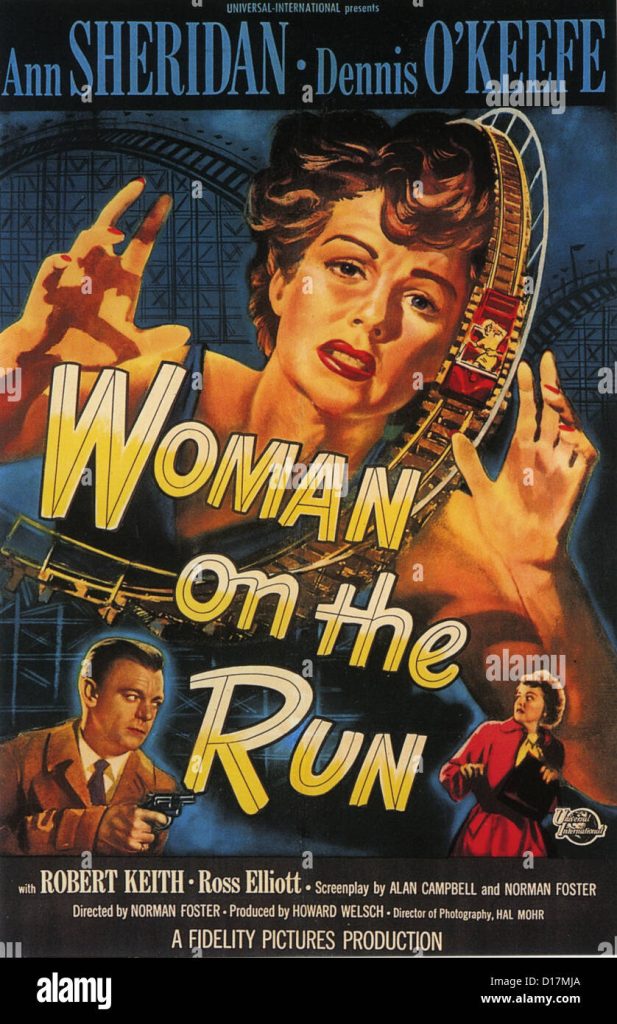

Sheridan reteamed with Sherman for “The Unfaithful” (1948), which found her charged with murder for the fatal stabbing of her ex-lover. She finished out her Warners contract with an uncredited bit as a Mexican prostitute in “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” (1948), done as a favor for director John Huston, and by playing a comely mine owner in “Silver River” (1948) opposite Errol Flynn. As a free agent, Sheridan made few remarkable films but many satisfying ones. Among these was Howard Hawks’ “I Was a Male War Bride” (1949) at Fox, in which she and co-star Cary Grant played American and French allies who fall in love while on a mission and employ the War Bride Act in order to remain together in the United States. Sheridan had the title role in Claude Binyon’s “Stella” (1950), as an upwardly mobile woman duped into helping her hayseed relatives cover up an accidental death, and received top billing for George Sherman’s “Steel Town” (1952), a class conscious melodrama co-starring John Lund and Howard Duff. She took a producer’s role for Norman Foster’s “Woman on the Run” (1950), in addition to headlining as a San Francisco housewife who works with newspaper reporter Dennis O’Keefe to track down her errant husband, material witness to a gangland murder.

Less in demand as she approached middle age, Sheridan shifted the focus of her labor to live television, appearing in episodes of such anthology series as “Schlitz Playhouse of Stars” (CBS, 1951-59), “Playhouse 90” (CBS, 1956-1961) and “The Ford Television Theater” (NBC, 1952-57). In 1965, the year she turned 50, she joined the ranks of fading Hollywood stars agreeing to lend their big screen credibility to the medium of daytime drama and appeared in the second season of the NBC soap opera “Another World” (1964-1999). Just as discriminating in the downward arc of her career as she had been at its apex, Sheridan passed on the part of a French brothel owner in Norman Jewison’s “The Art of Love” (1965), a role that went instead to Ethel Merman. In 1966, she married actor Scott McKay. She capped her career as the star of the Western sitcom “Pistols ‘n’ Petticoats” (CBS, 1966-67). Diagnosed during the first (and only) season with esophageal cancer, Ann Sheridan died at age 51 on Jan. 21, 1967.

by Richard Harland Smith