Dan O’Herlihy obituary in “The Guardian” in 2005.

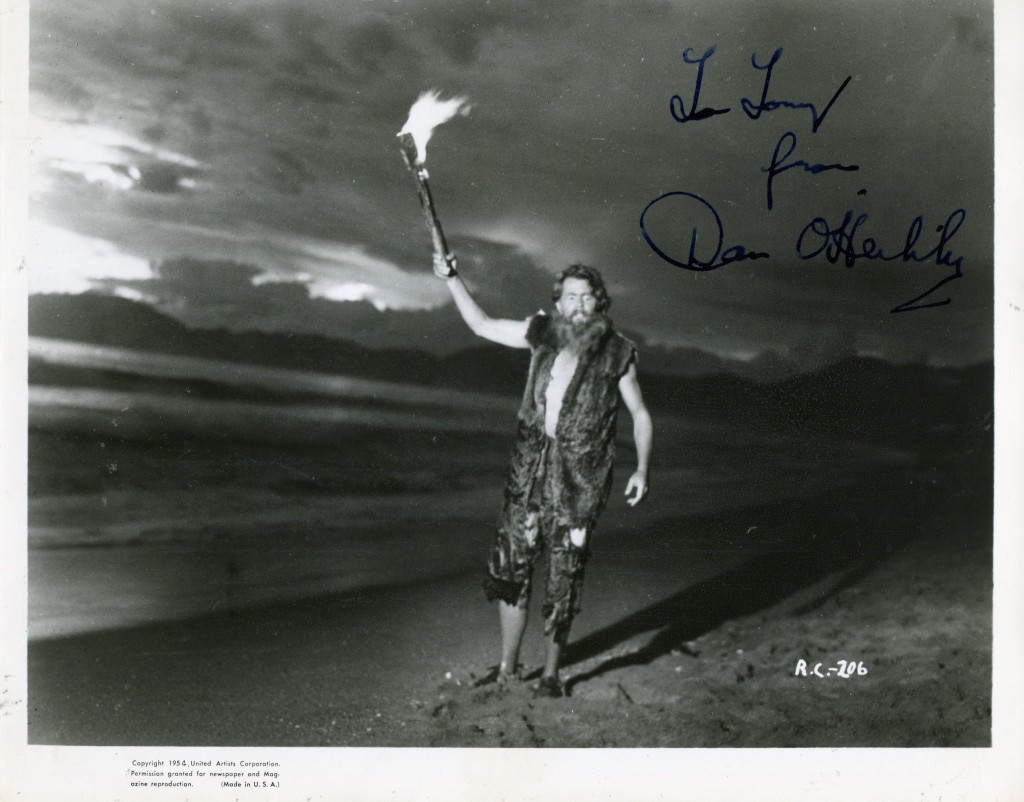

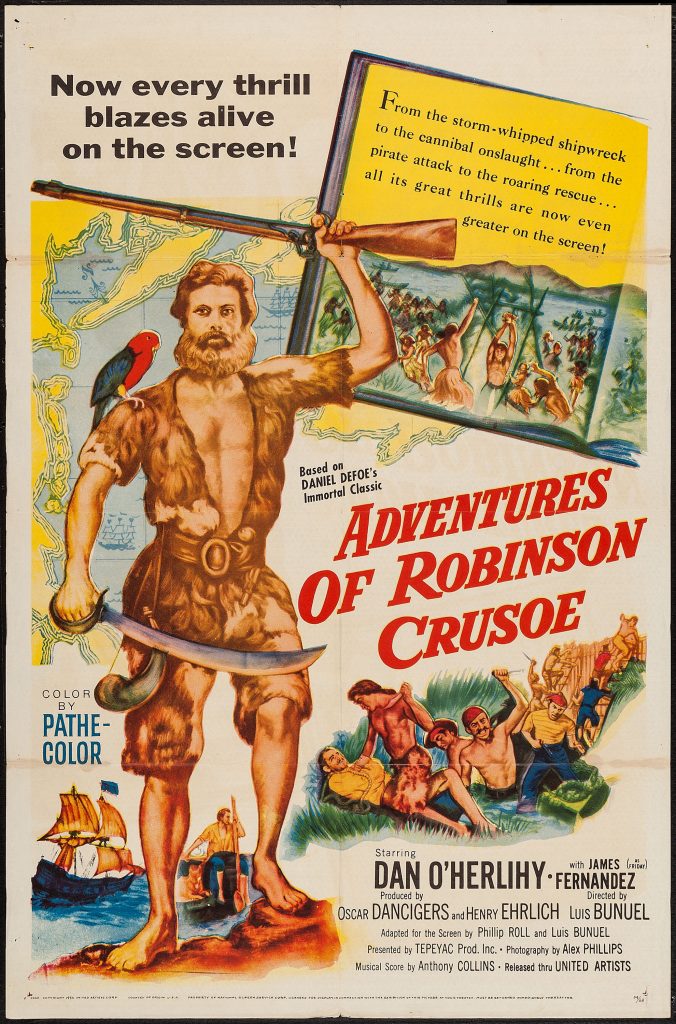

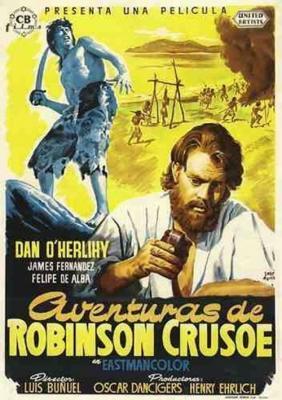

When Luis Buñuel, during his long exile in Mexico from Spain, was preparing to shoot The Adventures Of Robinson Crusoe (1952), his producers suggested Orson Welles for the title role. But as Buñuel sat down to watch Welles in the film of Macbeth, he immediately thought him “too big and too fat” for the part of the famous castaway. However, the moment the dashing and handsome Dan O’Herlihy, who has died aged 85, appeared as Macduff, Buñuel had found his Crusoe.A film in which an actor is alone on screen for 60 of the 90 minutes running time would seem a foolhardy venture, but the splendid Pathecolour photography, expert editing and O’Herlihy’s well-shaded performance, never allowed it to pall. With superb skill and grace, O’Herlihy moves from a clever but naive youth to the grizzled patriarch, earning himself an Oscar nomination.

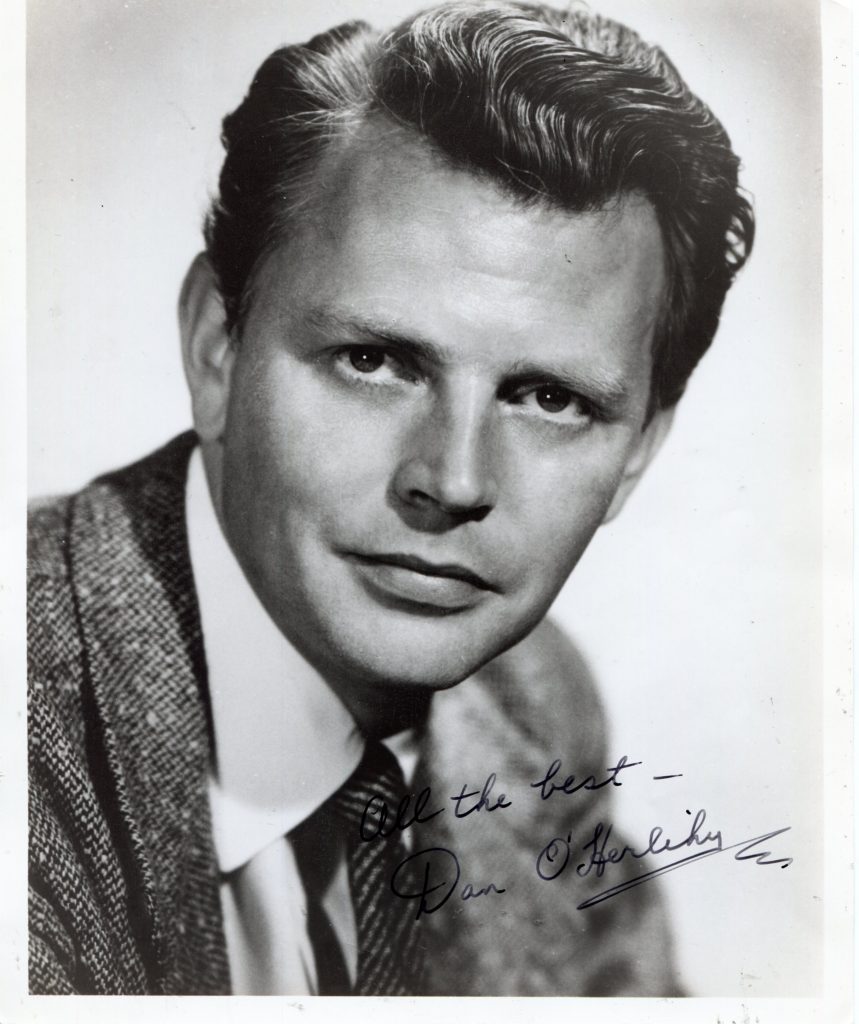

The 29-year-old O’Herlihy had been brought to America by Welles for Macbeth (1948) after having made an impression in his film debut as an IRA gunman in Carol Reed’s Odd Man Out (1947). The Wexford-born Irish actor, who had taken up acting to pay for his architectural studies at the National University of Ireland, had already gained a reputation at Dublin’s Gate Theatre (where the teenage Welles had begun his career) in around 50 plays, including the leading role in the first production of Sean O’Casey’s Red Roses For Me (1943). In the text of the play, O’Casey describes Ayamonn Breydon, the working-class Protestant hero, as “tall, well built, twenty-two or so, with deep brown eyes, fair hair, rather bushy, but tidily kept, and his face would remind an interested observer of a rather handsome, firm-minded, thoughtful, and good-humoured bulldog”.O’Herlihy, who eloquently uttered the rousing climactic patriotic speech, fitted the role perfectly. Macbeth led to a 50-year career in Hollywood and on US television, though few leads were forthcoming.

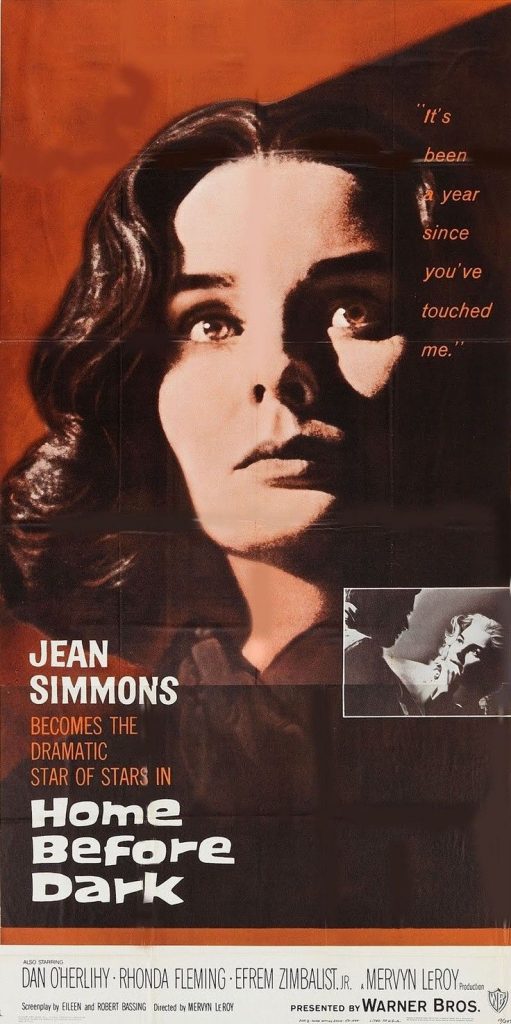

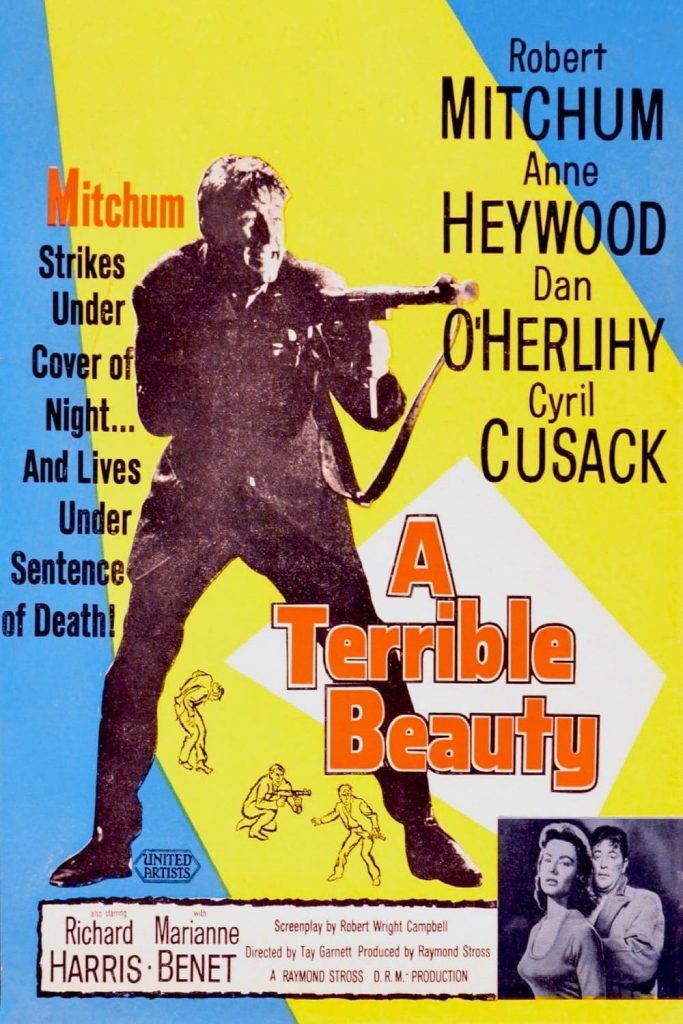

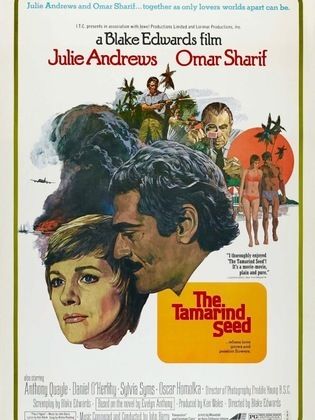

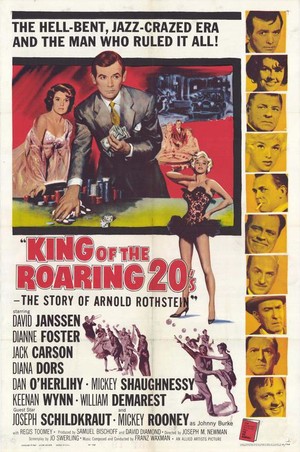

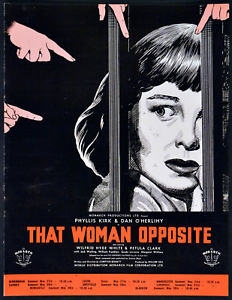

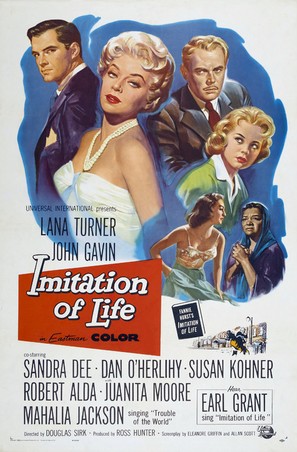

Apart from Robinson Crusoe, one of them was as Alan Breck in a shoestring version of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped (1948) opposite Roddy McDowall (Malcolm in Welles’s Macbeth) as David Balfour. This was followed by several sterling supporting roles in a number of undistinguished swashbucklers such as At Sword’s Point (1952) playing the son of one of the Three Musketeers, and as Prince Hal of Wales in The Black Shield Of Falworth (1954). He was cast as officers in Kiplingesque colonial adventures Soldier’s Three (1952) and Bengal Brigade (1954). He also appeared in Invasion USA (1952), a Red scare sci-fi film, in which he hypnotises patrons drinking at a bar into believing America has been attacked by nuclear weapons.O’Herlihy was sophisticated in Douglas Sirk’s glorious melodrama Imitation Of Life (1959); brutal, in a return to the world of Odd Man Out, as a fanatical, club-footed IRA leader in A Terrible Beauty (1960), and over-the-top in the title role of The Cabinet Of Caligari (1962), a silly remake of the silent expressionistic classic.

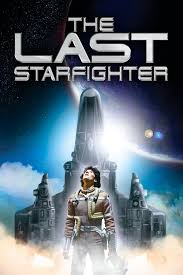

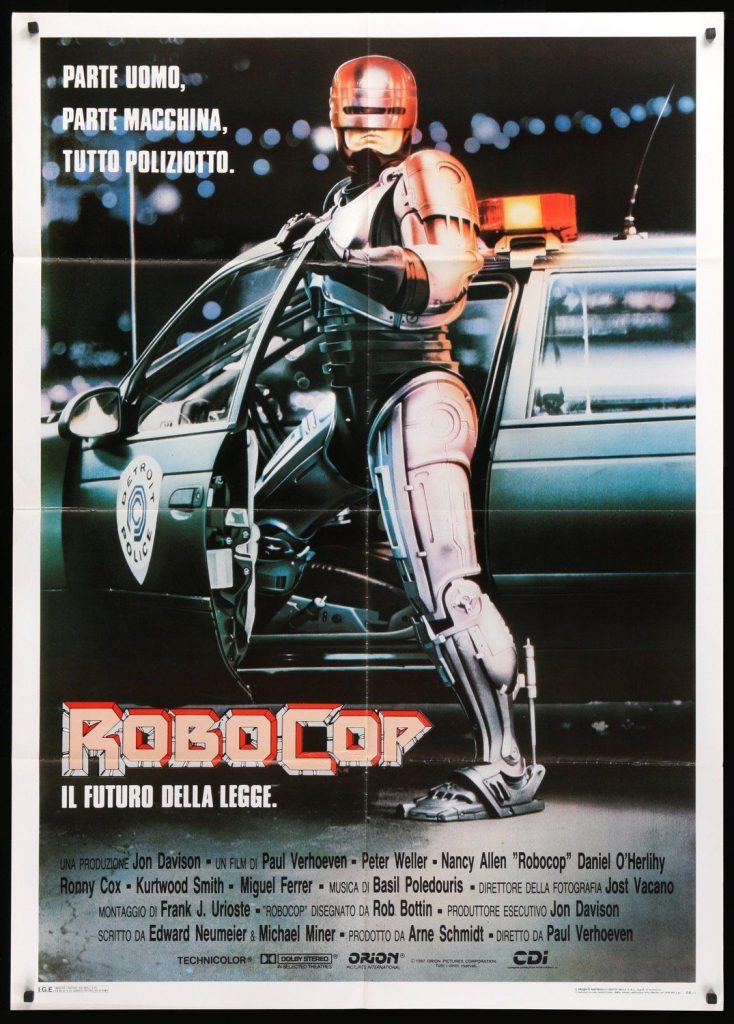

One of his best roles in the 1960s was in Sidney Lumet’s Fail Safe (1964) as Brigadier General Black, ordered by President Henry Fonda to drop an atomic bomb on New York City to show the Russians that bombing Moscow was an error.Television series, including The Long Hot Summer (1965), ironically in the role played by Orson Welles in the film version; Colditz (1972), Nancy Astor (1982) and David Lynch’s Twin Peaks (1992) kept him busy. In films, he was Franklin D Roosevelt in MacArthur (1977), starring Gregory Peck, and made himself known to a new generation as the mad toy tycoon in Halloween III: Season Of The Witch (1982), as a lizard-like alien in The Last Starfighter (1984), and eerily effective as the cold-blooded cyborg corporation mogul in Robocop (1987) and Robocop 2 (1990).It was all a long way from his Irish theatrical beginnings, though he recouped some of it in John Huston’s melancholically nostalgic valedictory film The Dead (1987), based on a James Joyce short story, in which he played Mr Brown “the gentleman not of our persuasion”.

Dan O’Herlihy is survived by Elsa Bennett, his wife of 59 years, two daughters and three sons.

· Daniel O’Herlihy, actor, born May 1 1919; died February 17 2005

His Guardian obituary by Ronald Bergan can also be accessed here.

Dictionary of Irish Biography:

O’Herlihy, Dan (Daniel Peter) (1919–2005), actor, was born 1 May 1919 at Odessa Cottage, Wexford town, son of John Robert O’Herlihy, a civil servant from Cork who later worked in the Department of Industry and Commerce, and his wife Ellen (née Hanton), from Wexford; they had at least one daughter, and a younger son, Michael O’Herlihy (1929–97), a television director. The family moved to Dublin when Daniel was one year old. Educated at CBS Dún Laoghaire, as a teenager he developed literary ambitions. On entering UCD, he applied to study law, but rapidly switched to architecture, which allowed him to use his drawing skills. While a student he published political cartoons in Irish newspapers, under the initials TOC.

Enlisted despite his minimal acting experience to perform in a production of the UCD dramatic society when a cast member walked out two days before an amateur festival, O’Herlihy accepted the offer in a spirit of adventure, won a medal, and was offered a part in a play at the Abbey theatre. He appeared as a ‘semi-pro’ in about sixty Abbey productions, but was turned down for the permanent company because Ernest Blythe (qv) thought his Irish insufficient (though he spoke and wrote Irish fluently). He also appeared in Gate theatre productions, and joined touring companies during the holidays. He played Major Sirr (qv) at the Gate in ‘Lord Edward’ (1941) by Christine Longford(qv), and took the lead role of Ayamonn Breydon in the world premiere at the Olympia theatre of ‘Red roses for me’ (1944) by Sean O’Casey (qv). His commitment to acting being motivated in part by a desire to supplement his allowance of half a crown a week from his father, he further augmented his income by working as a relief announcer on Radio Éireann.

After graduating from UCD, O’Herlihy worked part-time for one year in Dublin Corporation’s architecture department, surveying the city’s buildings to determine how they might be protected against air raids. He married (16 August 1945) Elsie Bennett, a wartime WAAF and TCD pre-medical student; they had three sons and two daughters. (In a favourite anecdote, he described his future father-in-law asking how he would support his daughter and a family on an architect’s salary, and his provoking scorn by observing that he also acted in the evenings; when O’Herlihy further asserted that he would make a fortune in Hollywood, he was thrown out of the house.) He abandoned architecture as a profession after landing roles in two films with Irish settings (but shot at Denham Studios, England): Hungry Hill(1947, dir. Brian Desmond Hurst) and Odd man out (1947, dir. Carol Reed); both films paid more for one day’s work than two months as an architect. (He retained a lifelong interest in architecture, and a sense that he was an architect who happened to act; he sometimes designed and/or built his own houses and those of friends and family. His last residence, in Trancas Canyon, Malibu, California, was designed by his architect son Lorcan, and built by O’Herlihy himself.)

O’Herlihy was brought to Hollywood in 1947 by the agent Charles Feldman, with whom he fell out after refusing two studio contracts: ‘I didn’t want anyone to own me.’ O’Herlihy feared that as a studio contract player he could be forced to accept unsuitable roles, thus destroying his long-term prospects. Through a period of considerable financial strain on his young and growing family, he initially got by on radio work, which dried up with the spread of television. Turning down the worst film scripts and accepting the average, in the expectation that good parts would come in time, O’Herlihy deferred to his wife’s judgment of scripts; she also helped him to rehearse as ‘unpaid script girl’. In later interviews the couple observed that the shared struggles of this period helped them to achieve a notably successful and remarkably plainspoken marriage.

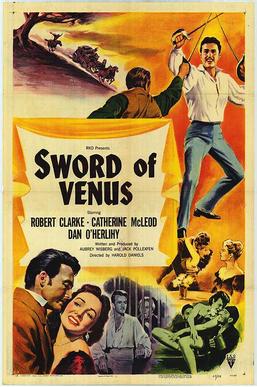

Between 1948 and 1955 O’Herlihy appeared, mostly as a supporting player, in thirteen costume drama pictures; these were mainly low-budget productions, such as William Beaudine’s adaptation of Kidnapped (1948), from the adventure novel by Robert Louis Stevenson, for the ‘Poverty Row’ studio Monogram, in which O’Herlihy played Alan Breck Stewart to the David Balfour of Roddy McDowall. Although O’Herlihy’s height (over 6 ft (1.83m)) and reddish-blond good looks were well-suited to this genre, he actively resisted typecasting. In Sword of Venus (1953, dir. Harold Daniels), he was made up effectively to play the role of the elderly villain. Such versatility laid the basis for his later success as a character actor, with a reputation as an ‘actor’s actor’, placing a strong emphasis on spontaneity.

Throughout his career O’Herlihy remained involved in theatre, which he regarded as the actors’ medium par excellence (film being a director’s medium). He made his only Broadway appearance as Charles Dickens in ‘The ivy green’ (1949) by Mervyn Nelson. In 1955 he co-founded the Hollywood School of Drama with his boyhood friend and lifelong associate Charles Davis. When a bit player fell ill during the school’s production of ‘Finian’s rainbow’, O’Herlihy recruited Marlon Brando – who shortly before had lamented to O’Herlihy that he had not appeared on stage for some time – to take on the part for two nights (to the surprise of audience members). In later life O’Herlihy remarked that the writer was the central creative force in drama and that he would have liked to have been a writer. He wrote several unproduced scripts, and between 1985 and 1997 produced a one-man show of his own devising, ‘Five men with a pen’, in which he impersonated writers and recited from their works, including W. B. Yeats (qv), James Joyce (qv), George Bernard Shaw (qv), and Mark Twain. In the television movie Mark Twain: behind the laughter (1979), he gave a much-admired performance as the elderly Twain recalling his life, with his actor son Gavan playing Twain’s younger self.

In 1948 O’Herlihy joined Orson Welles’s Mercury Theatre, and played Macduff in Welles’s low-budget film of Macbeth (1948), exercising his architectural skills to design most of the sets, and translating additional dialogue written by Welles into Irish. Welles did not credit O’Herlihy’s work as set designer, and their later relations were tense. O’Herlihy’s performance in the film led in time to his breakthrough role, the lead in The adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1954); the director, Luis Buñuel, responding to a proposal that he cast Welles in the role, screened Macbeth and fixed instead on O’Herlihy. Filmed over a lengthy period in Mexico, the story of a shipwrecked man surviving for twenty-eight years on a remote island demanded that O’Herlihy be alone on screen for the film’s first fifty minutes, and that he deploy his acting skills to portray his character ageing from young manhood to late middle age. He also appears briefly as Crusoe’s elderly father, glimpsed in a fever-driven nightmare. Critically praised for the performance, O’Herlihy received his only Academy Award nomination, for best actor; he was runner-up in the voting to Marlon Brando for On the waterfront (the other nominees were James Mason for A star is born , Humphrey Bogart for The Caine mutiny, and Bing Crosby for The country girl). O’Herlihy received a letter from his father praising his success in his ‘hobby’ and asking when he would return to his profession (i.e., architecture).

Beginning in the mid 1950s O’Herlihy appeared frequently on television, some such performances being among his best work. He generally refused to make long-term commitments to a television series, believing that, while potentially profitable, they were especially vulnerable to commercial constraints and could inflict long-term career damage through typecasting. (He turned down a role in the hit 1960s series Lost in space.) The major exceptions were The travels of Jaimie McPheeters (1963–4), a western in which he played the showman father of the juvenile protagonist (Kurt Russell), and The long hot summer (1965–6), for which he was recruited mid-series to replace Edmond O’Brien (who had quarrelled with the producers) as the town boss, Will Varner.

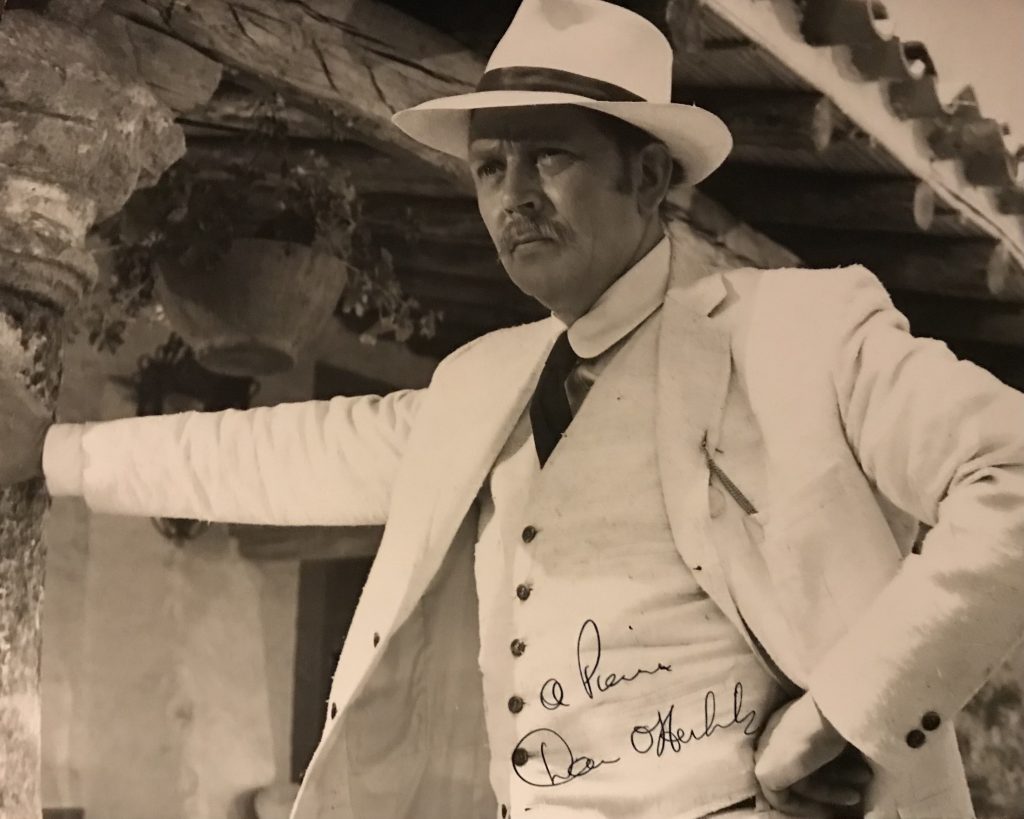

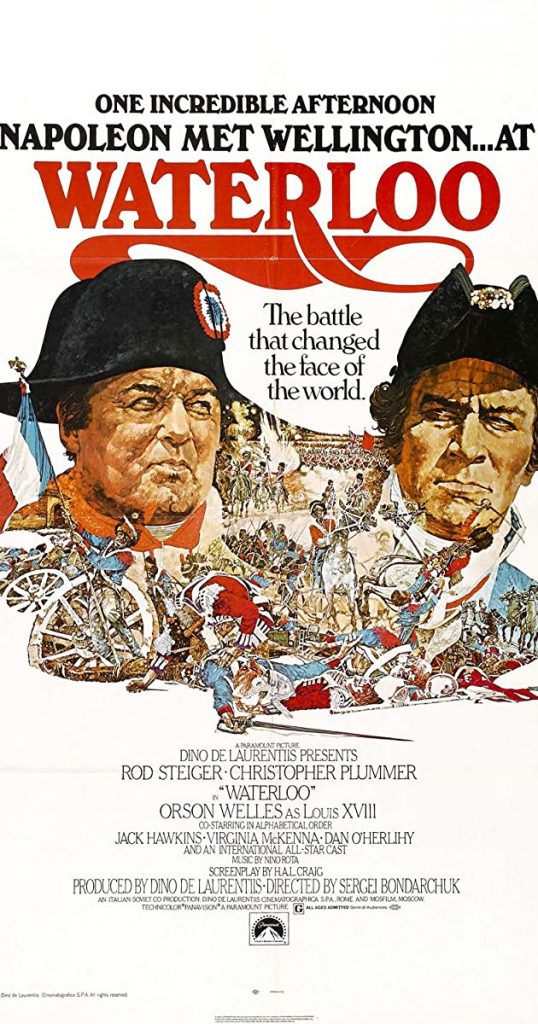

O’Herlihy’s career advancement was hindered by consequences of his determined and forceful character. He continued to refuse unsuitable roles, courted notoriety with outspoken political views, and clashed bitterly with his powerful talent agency. Espousing liberal political views from the 1950s (he supported the Democratic presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson, the darling of the decade’s liberal intellectuals), he moved further leftward over time, arousing suspicions in some quarters of his being a communist. His remark that FBI director J. Edgar Hoover – whom the cast of a film were about to meet – would be better described not as an American patriot but as a traitor resulted in his being informally shut out from future work for Warner Brothers Pictures. Some of his films had political themes. In Fail-safe (1964, dir. Sidney Lumet), which depicted an accidental American nuclear attack on Moscow, O’Herlihy plays a ‘dovish’ American air force general who argues for restraint, and is obliged by the president (Henry Fonda) to destroy New York to convince the Soviets that the attack on them was accidental. O’Herlihy expressed satisfaction that the film deconstructed the Cold War image of Russians as ruthless fanatics. His contempt for Russophobia increased owing to a lengthy period in 1969 in Uzhgorod, western Ukraine, during the filming of Waterloo (1970, dir. Sergei Bondarchuk), in which he played Marshal Ney. (Personal sympathy for Russians did not equate to admiration for the Soviet system; he noted that the USSR had its own rigid class system, and predicted a future youth revolt resembling that of the late 1960s in the West.) O’Herlihy’s portrayal of Franklin D. Roosevelt in MacArthur (1977, dir. Joseph Sargent) is regarded as one of his finest, and reflected the intellectual fascination with power and its workings that informed his political commitment.

With the decline of the classic studio system, agents became the major brokers in Hollywood; in 1958 the powerful talent agency MCA acquired Universal Studios, creating a conflict of interest in its representation of clients. When O’Herlihy resisted pressure to reprise the Robinson Crusoe role for a Universal television series (stating that he was loathe to go from Buñuel to TV hack direction), the agency ordered him ‘put on ice’. O’Herlihy fired the agency, went public with his complaints, and gave evidence at an anti-trust inquiry, mounted by the Justice department under Attorney General Robert Kennedy, which forced MCA to dissolve its agency component so as to retain control of Universal and its music operations. O’Herlihy’s role in the agency’s defeat was remembered by MCA executives, who exercised considerable power within Hollywood; their enmity inflicted considerable short-term damage on his career and contributed to his spending more time in Ireland.

O’Herlihy had worked in Ireland on the filming of A terrible beauty(1960; dir. Tay Garnett) as a local IRA commander collaborating with Nazi Germany in the 1940s; the film starred Robert Mitchum. Maintaining that his regular visits to Ireland prevented him from romanticising the country, he noted that the socially ambitious Irish middle classes of the relatively affluent 1960s and 1970s resembled their counterparts in California’s San Fernando Valley. He compared the speculatively redeveloped Dublin cityscape of the period to a dishevelled and gap-toothed old man, remarking that it was easy to see from the standard of new building that most Irish architects had emigrated. He and his family lived in Ireland in the mid 1960s and again in 1970–75. Briefly rejoining the Abbey company, he played the lead role of the JFK-emulating publican in the premiere of Tom Murphy’s ‘The White House’ (1972). Asked to become a Labour candidate in the 1973 general election, he declined owing to the impossibility of combining electoral office with the extensive travelling required by his acting career. Finding it necessary to be American-based to remain in demand as a Hollywood actor, and because his children had grown up as Americans, O’Herlihy moved back to America in 1975; he took American citizenship in 1980.

Late film roles included Grig, the friendly alien ‘iguana man’, in The last starfighter (1984; dir. Nick Castle); the Old Man (boss of the malevolent corporation OmniCorp) in RoboCop (1987; dir. Paul Verhoeven, whom O’Herlihy regarded as one of the best contemporary directors) and in RoboCop 2 (1990; dir. Irvin Kershner); the tipsy protestant guest Mr Brown in The dead(1987), adapted by John Huston (qv) from the story by James Joyce; and the sawmill owner Andrew Packard in six episodes of the surreal television serial Twin Peaks (1990–91). His last role was as Joseph Kennedy Sr in the television movie The Rat Pack(1998).

O’Herlihy died 17 February 2005 in Malibu, California, and is buried in St Ibar cemetery, Wexford. Four of his five children worked in theatre and film: Gavan, Cormac, and Patricia as actors, and Olwen as a producer and visual artist. His grandson Colin O’Herlihy became an actor, and his granddaughter Micaela O’Herlihy a multimedia artist.

Sources

GRO (birth cert.); O’Herlihy Papers, UCD Archives, IE UCDA P202 (permission of O’Herlihy family required for consultation; includes catalogue with biographical introduction and filmography; see esp.: P202/18 (collection of published interviews); P202/22 (outline of projected documentary on O’Herlihy); P202/110–11 (Robinson Crusoe material); P202/238 (biographical material); P202/240 (obituaries)); Des Hickey and Gus Smith (ed.), Flight from the Celtic twilight (1973); Kevin Rockett, The Irish filmography: fiction films 1896–1996 (1996); Revisiting Fail-safe, short documentary on 2000 DVD release of Fail-safe; Ir. Times, 19 Feb. 2005; Daily Telegraph, 19 Feb. 2005; Sunday Independent, 20 Feb. 2005; Independent (London), 21 Feb. 2005; Internet Movie Database, www.imdb.com; Internet Broadway Database, www.ibdb.com; Irish Playography, www.irishplayography.com (websites accessed July 2011); information from Olwen O’Herlihy Dowling (daughter