Roger Rees obituary in “The Guardian” in 2015.

Roger Rees, who has died aged 71 after suffering from cancer, was an outstanding associate of the Royal Shakespeare Company, who made his name in the title role of Nicholas Nickleby in 1980, winning an Olivier best actor award in London and a Tony best actor on Broadway before he moved to New York in the late 1980s, taking US citizenship in 1989, and becoming known to millions in two top television shows.

In Cheers, he was Kirstie Alley’s love interest, as the millionaire industrialist Robin Colcord; in The West Wing, he was the British ambassador to Washington Lord John Marbury. He became a go-to Brit on various US series, but returned briefly to Britain in 1988 to record the sitcom Singles, a sort of low-rent Cheers in a singles bar.

None of these roles exploited the vibrancy and emotional fizz Rees exhibited on stage, especially in a hot streak at the RSC which took him from one suicidal ditherer, Semyon, in the first UK production of Nikolai Erdman’s 1928 comic classic The Suicide in 1979, to a 1984 Hamlet in the same Stratford-upon-Avon season as Antony Sher’s Richard III and Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V (Branagh was Laertes to his Hamlet). The electrifying Nicholas Nickleby came in between.

Like Ben Kingsley, he languished in small parts at the RSC when he first joined in 1967, but both he and Kingsley became stars, and associate artists, in the Trevor Nunn and Terry Hands era. There was always a febrile intensity about Rees, a quickness and charm that could move an audience to tears or laughter, often both, at the speed of light; he was a superb and touching Tuzenbach in Nunn’s brilliant 1978 production of Three Sisters, moustachioed and bespectacled, pleading with Emily Richard’s Irina to say something before he went off to be shot in the duel.

He returned to the London stage in 2010 as Vladimir in Sean Mathias’s revival of Waiting for Godot at the Haymarket; he took over the role, opposite Ian McKellen’s Estragon, from Patrick Stewart, and was spryer and infinitely more cheerful than Stewart, though more of a junior partner. He remained close friends with many old RSC colleagues; McKellen and Stewart, but also Judi Dench (he was Malcolm in the great 1976 Dench/McKellen Macbeth). With Dench, Rees sustained a comic ritual of exchanging sushi by special delivery at unexpected and inconvenient hours.

And then in 2012 he brought his solo show, What You Will, to the Apollo and seemed as puppyish and perennially youthful as ever as he mixed Shakespearean speeches with anecdotal gems (such as the story of Wilfrid Lawson, on a payday matinee, quelling a mutinous crowd as he lurched into the opening soliloquy of Richard III with: “If you think I’m pissed, wait till you see Buckingham … ”)

Rees was one of two sons of an Aberystwyth policeman, William Rees, and his wife Doris (nee Smith). The family moved to south London, where Roger attended Balham secondary modern school and the Camberwell School of Art; his drawing skills won him a place at the Slade. He had appeared only in Ralph Reader’s Gang Show at the Golders Green Hippodrome in 1963, and was painting scenery at the Wimbledon theatre in 1964 when a crisis of casting pitched him on to the stage as Alan Jeffcote, the juvenile lead in Stanley Houghton’s Hindle Wakes.

After a season at Pitlochry, he joined the RSC, gradually making his mark in the early 70s as Claudio in Much Ado About Nothing, Roderigo (the perfect comic gull: “I’ll go sell all my land”) in Othello, Gratiano in The Merchant of Venice and Posthumus in Cymbeline. He toured with the Cambridge Theatre Company as Fabian in Twelfth Night and Young Marlowe in She Stoops to Conquer before making a Broadway debut with the RSC as Charles Courtly in Dion Boucicault’s London Assurance in December 1974.

After Nickleby, Rees had another West End triumph as the pop fan playwright Henry in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing (1982), co-starring Felicity Kendal, at the Strand. Henry’s personal credo, delivered while wielding a cricket bat, of how ideas bounce more effectively from a hard, sprung surface, was a defining moment in the postwar theatre friction between politics and art, ideology and expression (“Screw the whale, save the gerund”) and all the better for shining in a play about love.

Rees’s transatlantic translation was also romantically motivated. He was in a relationship from 1982 onwards with the writer and producer Rick Elice (whom he married in 2011), and his Broadway and television work was increasingly shared with commitments as a director.

He won an off-Broadway Obie for his portrayal of a narcissistic doctor in John Robin Baitz’s The End of the Day (1992) and in 1995 he starred alongside Kathleen Turner, Eileen Atkins and Jude Law in Jean Cocteau’s Indiscretions (or Les Parents Terribles) on Broadway. He co-directed a Peter Pan prequel, Peter and the Starcatcher, written by Elice, in 2012 and scored, too, as the father in a 2013 revival of Terence Rattigan’s The Winslow Boy.

He had been appointed artistic director of the Williamstown theatre festival in Massachusetts in 2004 (he resigned in 2007), where he workshopped John Kander and Fred Ebb’s last musical, The Visit, starring Chita Rivera. The show finally came to Broadway in spring 2015, and Rees played Anton Schell, the doomed ex-lover of Rivera’s extravagant millionairess, but illness forced him to leave the show in late May, shortly before it closed.

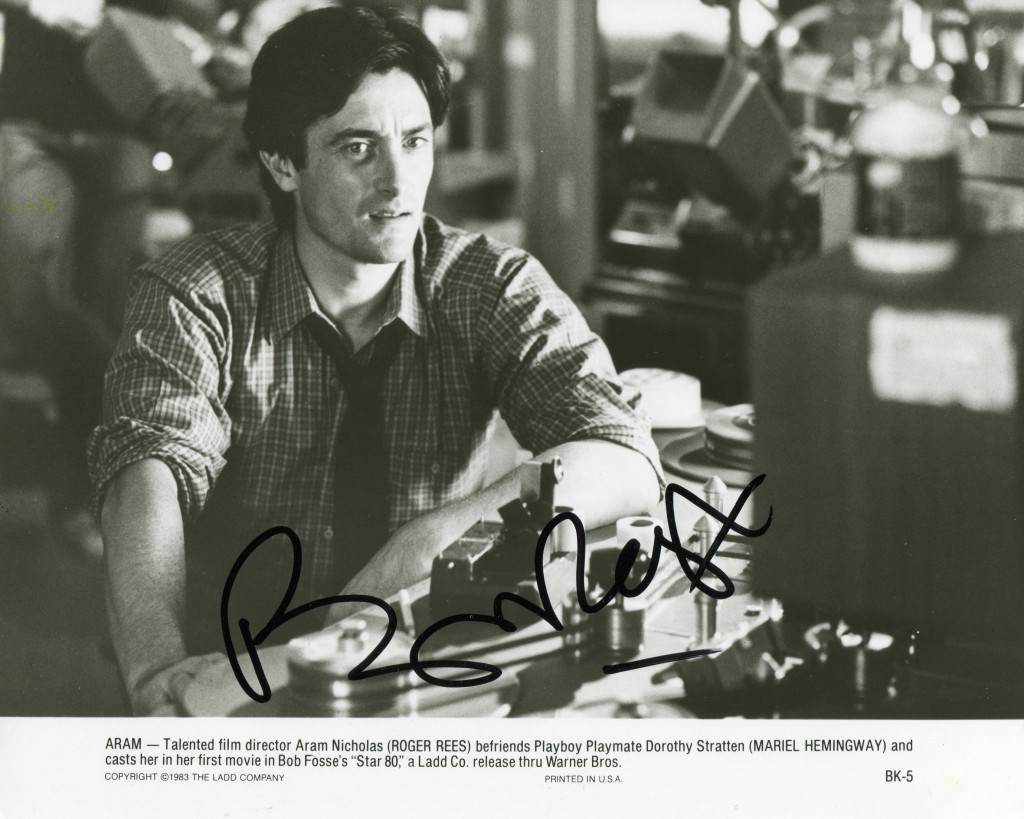

Rees made many films without ever matching the 1982 Channel 4 version of Nickleby, but he made an impression in Tony Tews’s God’s Outlaw (1986), as the impassioned Bible translator William Tyndale; in Mel Brooks’s Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1993), as the ludicrous, not so dastardly Sheriff of Rottingham; in Julie Taymor’s Frida (2002), starring Salma Hayek as Frida Kahlo and Alfred Molina as Diego Rivera; and in Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige (2006), starring Hugh Jackman and Christian Bale.

Rees is survived by Elice.

Michael Coveney

David Edgar writes: In 1976, I’d seen Roger Rees be unmatchably brilliant in the RSC’s musical Comedy of Errors. Three years on, I was asked to adapt Nicholas Nickleby, and he brought that genius to a part some thought less fruitful than the wonderful Dickensian grotesques which surrounded it.

The directors, John Caird and Trevor Nunn, had the idea that the actors would shift effortlessly from narrating the story to commenting on their character to playing it. The deftness with which Roger pulled off this post-Brechtian device was used to great comic effect (if he tried a line twice and it didn’t work, it was because it couldn’t), but also allowed him to chart the growth of an angry young man into a moral hero. He applied his unique talent for shaping a line both to a cod happy-ending Romeo and Juliet, and to the death of Smike, the orphan boy Nicholas has befriended. That moment proved the most heartbreaking any of us had ever seen.

When, after Nickleby’s transatlantic success, Roger moved to New York, he was rightly seen as a loss to the British but a gain for the American theatre. There were parts in later plays of mine I wish he could have played. But he played Nicholas Nickleby as well as it was possible for any actor to do.

• Roger Rees, actor, born 5 May 1944; died 10 July 2015