Dorothy Tutin obituary in “The Guardian” in 2001.

In many ways it was the misfortune of Dorothy Tutin, who has died aged 70 from leukaemia, to have been born into that generation of actors who bridged the gap between the classical grandes dames of the 1940s and the more modern performers of the 1960s. There remained something almost pre-war about her looks, demeanour and that distinctive and precise voice, speaking in what was once dubbed “Tutinese”.

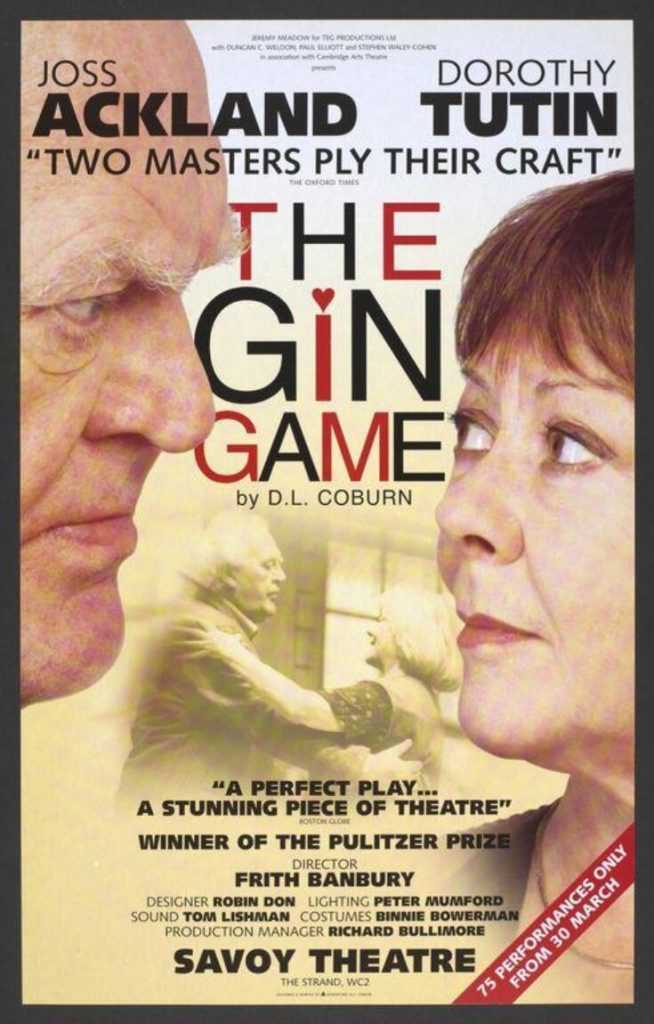

Her name was a benchmark for quality, but she was initially a reluctant actor. She became, however, a dedicated one, and although she was disgracefully underused in latter years, even in her last major stage performance, a revival of DL Coburn’s The Gin Game at the Savoy Theatre in 1999, she soared way above that rickety old play.

A solitary, pent-up child, she was much affected by the sudden death of her beloved 10-year-old elder brother Eric when she was six. Born in London and educated at St Catherine’s school in Bramley, Surrey, Tutin was determined to make a career as a musician, but abandoned that ambition at the age of 15, accepting, with a maturity beyond her years, that she did not have the talent.

It was her theatre-loving father who, impressed by her performance as a last-minute replacement in a school production of JM Barrie’s Quality Street, pushed his self-conscious daughter – who professed a horror at performing in public – towards the stage. Tutin often recounted how she tried to prevent her father from telephoning Rada to inquire about vacancies.

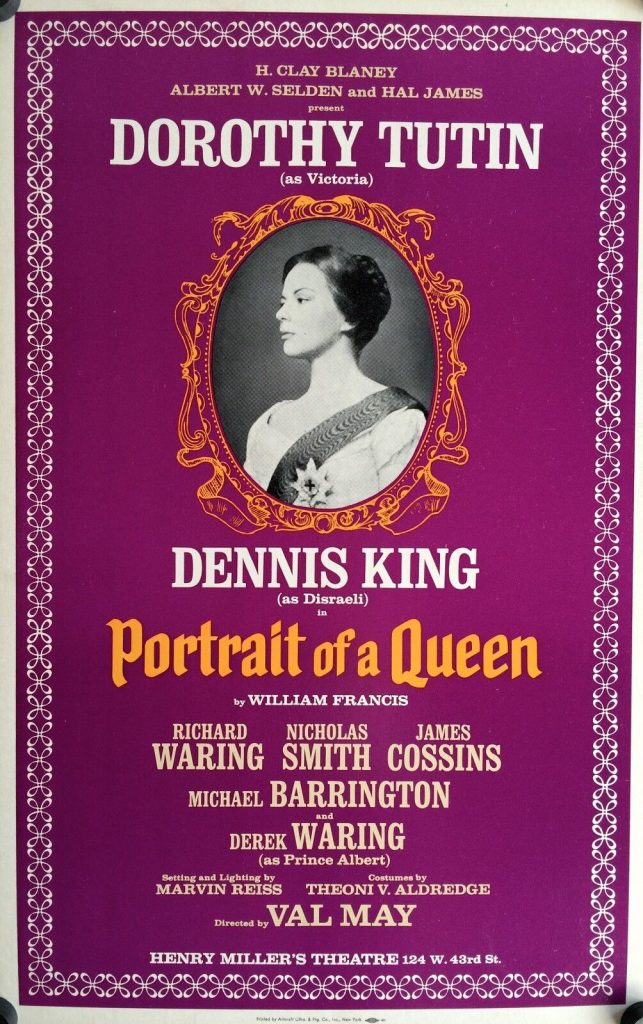

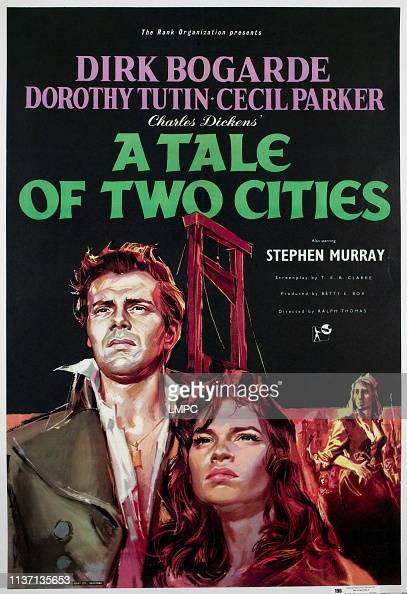

But it was there that she went, graduating in 1949 when only 19. Within the year she was playing Katherine in Henry V at the Old Vic. During the next 10 years she became one of the most celebrated but self-effacing stars of the British stage, notching up Juliet, Ophelia, Portia and Viola to great acclaim. Her film debut came in 1952 as Cecily in Anthony Asquith’s film version of The Importance Of Being Earnest. In later years she was to regret not making more films, but the 1950s was the age of the Rank starlet and Tutin did not fit the mould – and probably wouldn’t have wanted to.

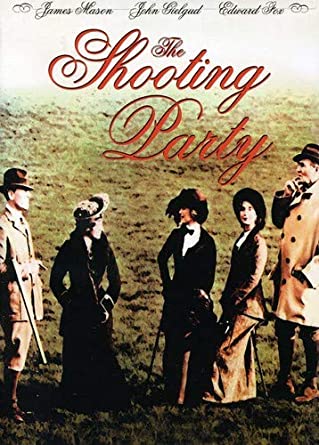

None the less, in 1984 she did star with James Mason, Edward Fox and Sir John Gielgud in the eve-of-first-world-war allegory, the critically acclaimed The Shooting Party.

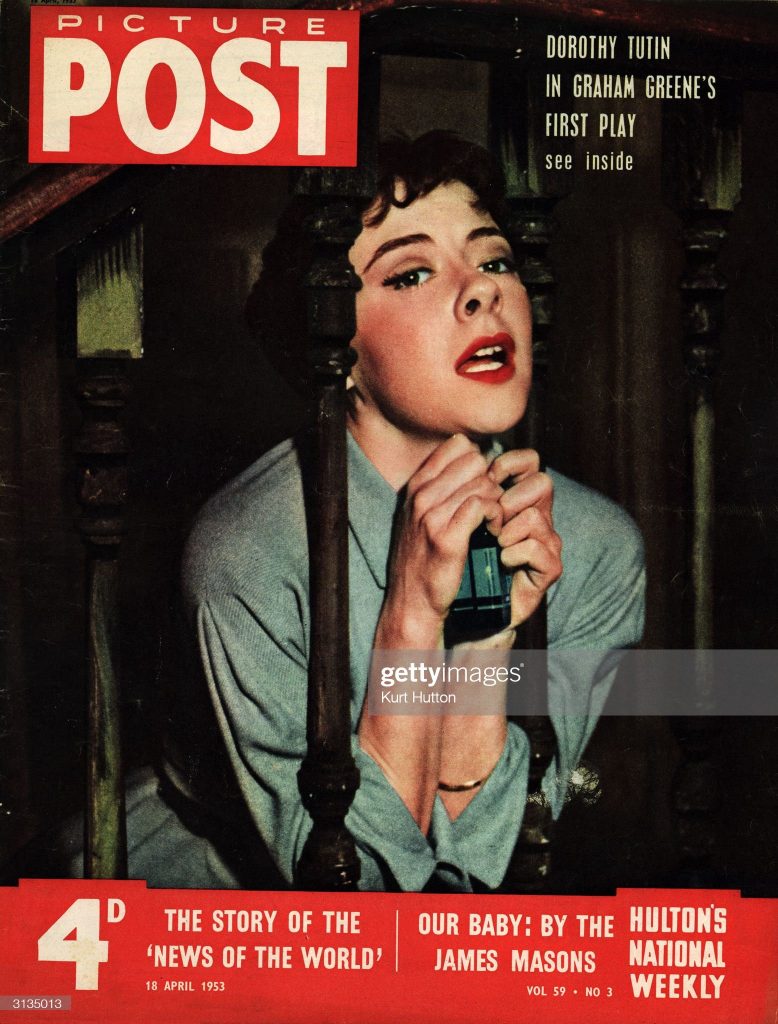

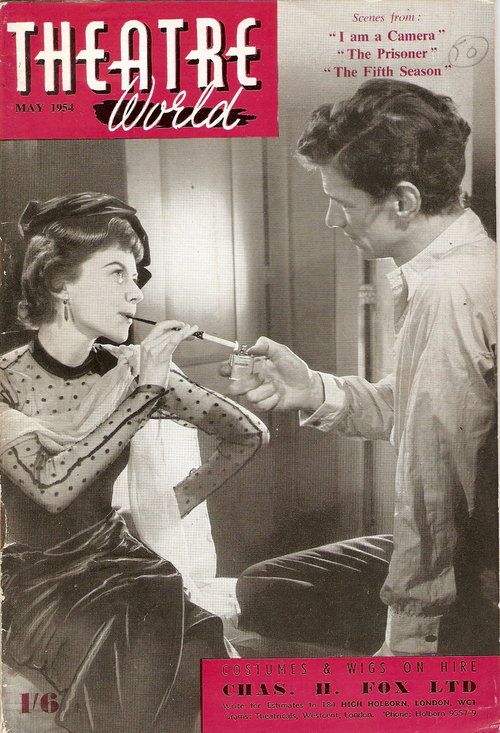

The stage was her métier, and she turned in memorable performances as Sally Bowles in I Am a Camera, Hedwig in The Wild Duck and, most notably, as the young Catholic girl Rose in the 1953 production of Graham Greene’s The Living Room. The critic Kenneth Tynan was entranced, describing her as being “ablaze like a diamond in a mine”.

There were signs, however, that she might burn out. Lacking self-confidence and plagued by ill-health, she was hospitalised several times during the 1950s, and took failure hard, blaming herself in particular for the lack of success of Jean Anouilh’s The Lark, in which she starred as St Joan in 1955. One of the regrets of her career is that she never played in Shaw’s St Joan .

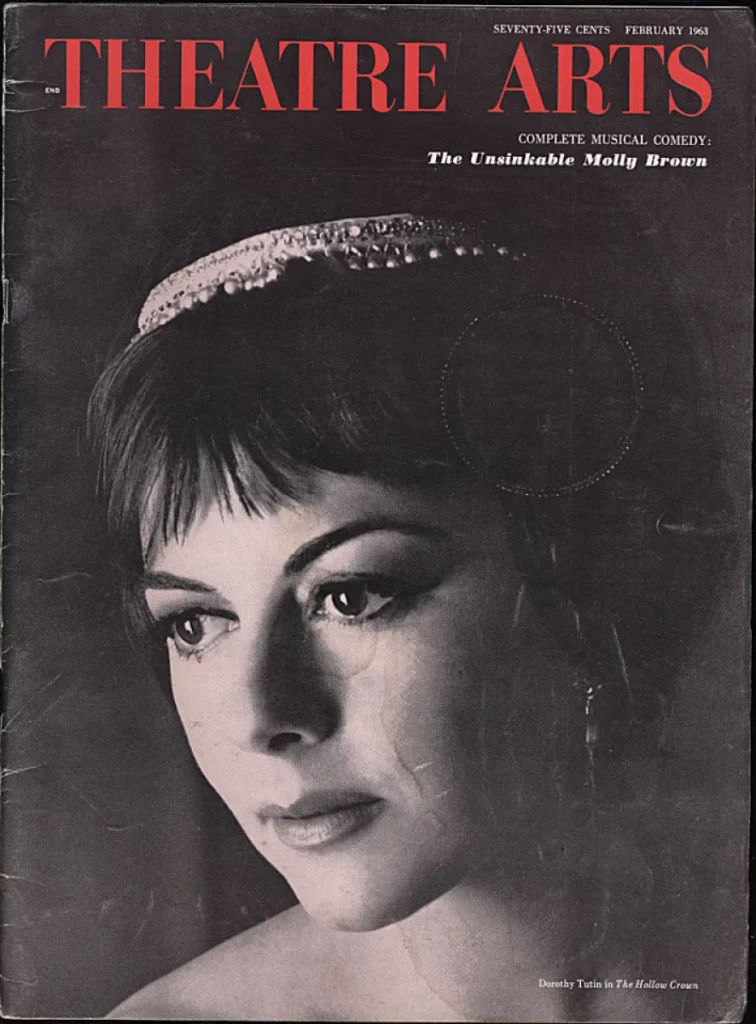

Championed by Peter Hall, Tutin was a key figure in the early days of the RSC at Stratford and London’s Aldwych theatre in the early 1960s. She played Desdemona, Varya in The Cherry Orchard, Polly Peachum in The Beggar’s Opera and, later in the decade, Rosalind.

By the early 1970s, partly preoccupied by marriage and motherhood, Tutin was seen far less in the theatre. While she had been doing the classics, the British theatre had changed, having been dragged kicking and screaming into the 20th century. She had little or no reputation for doing the new plays then in vogue.

But, as ever with Tutin, still waters ran deep. When producers and directors had the courage to cast her against type, she always surprised. The pretty, Squirrel Nutkinish features disguised something much rawer and disturbing, as was evidenced as early as 1961 by the violence of her performance as Sister Jeanne in John Whiting’s The Devils.

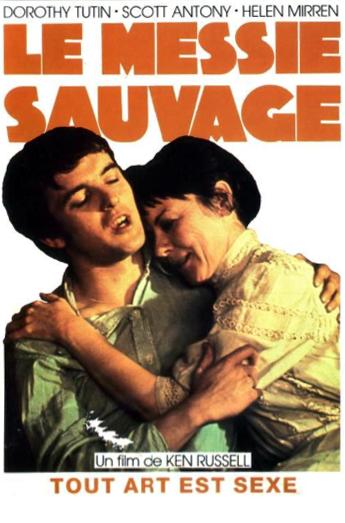

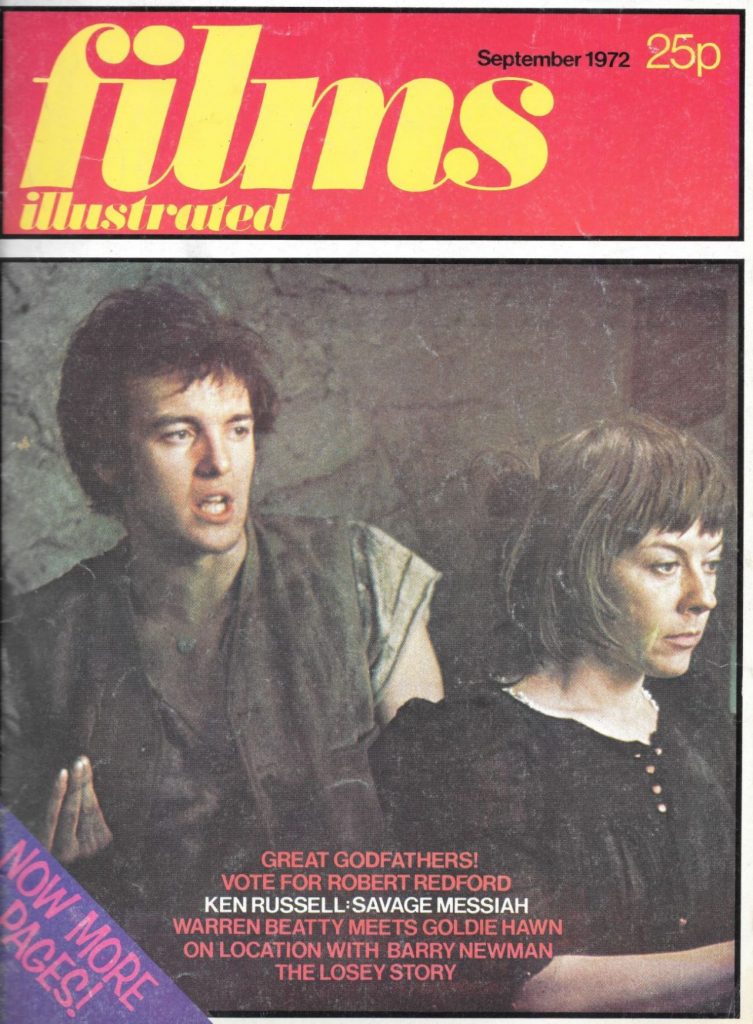

As Bernard Levin noted in 1977 when she was playing Lady Macbeth and Lady Plyant in Congreve’s The Double Dealer at the National: “She is tiny. She looks too sweet for anything but sweet parts; and although her voice is musical, it doesn’t naturally express hard emotion. Yet she has an astonishing edge as Lady Macbeth. As Cressida, she was a wisp of rippling carnality. Her Sophie Brzeska in Ken Russell’s Savage Messiah was violently earthy, sexual: all the things a Meissen porcelain figure shouldn’t be able to be.”

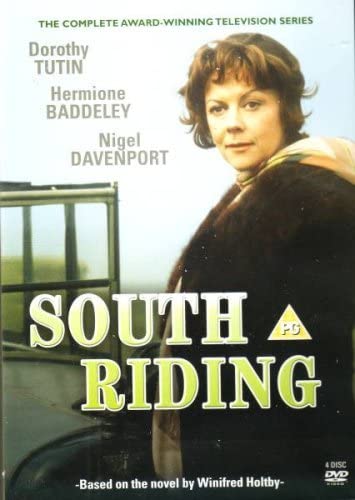

Regrettably, in later years she seldom got to show her talents to their best. Television and the boulevard drama of the West End and Chichester were her haunts in the 1980s and 90s.

She did, however, have an affinity with Pinter. She was in the original cast of Old Times in 1971, and in 1985 gave a desperately moving performance, both on TV and in the West End, in A Kind Of Alaska. She played Deborah, a teenager struck down by encephalitis lethargia who awakens 29 years later when given the drug L-DOPA. Tutin was mesmerising as this uncomprehending, terrified middle-aged Sleeping Beauty who still perceived herself as a tomboy teenager, and this should have given a boost to her career. Alas, it didn’t. She was pained by her lack of job opportunities, telling the Guardian in 1991: “You may as well ask, why aren’t you employed more, Miss Tutin? One can get depressed.”

It seemed such a waste. It was Caryl Brahms, writing in Plays And Players in 1960 when she was in her prime, who captured her essence: “Miss Tutin is a small-scale hurricane. And once she is unleashed upon a part, there is bound to be, one feels, a short, sharp tussle. But Miss Tutin comes out on top, and having subdued it to her temperamental and technical measure, parades in it, all smiles and sequinned tears. She can be gay, pathetic, lively, stunned – part minx, part poet, part sex-kitten. A comedienne of skill and a pint-sized tragedienne.”

She loved music and solitude, enjoying lonely walks on the Isle of Arran. She is survived by her husband, the actor Derek Waring, and a son and a daughter.

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.