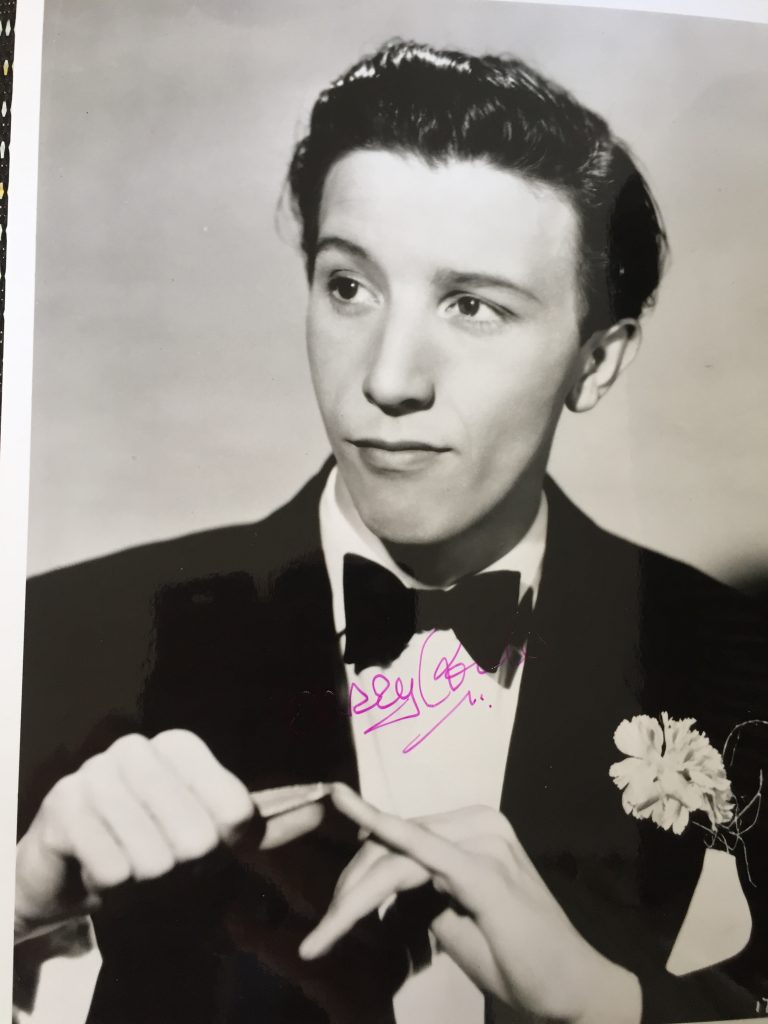

Harry Fowler obituary in “The Guardian”

Harry Fowler was a wonderful cheeky cheerful juvenile British character actor who enlivend many films of the 1940’s and 50’s.. He was born in Lambeth, London in 1926. He gave a wonberful performance in “Hue and Cry” in 1947. Other films ivclude “Angels One Five”, “I Believe in You” in 1952 losing Joan Collins to the very gloomy Laurence Harvey, “West of Suez” and “Laurence of Arabia”. Sadly Harry Fowler passed away in January 2012.

Brian Baxter’s “Guardian” obituary:

While working on the classic Ealing comedy Hue and Cry in 1947, the actor Harry Fowler, who has died aged 85, was given sage advice by one of his co-stars, Jack Warner: “Never turn anything down … stars come and go but as a character actor, you’ll work until you’re 90.”

Fowler took the suggestion and proved its near veracity. Between his 1942 debut as Ern in Those Kids from Town until television appearances more than 60 years later, he notched up scores of feature films and innumerable TV shows, including three years as Corporal “Flogger” Hoskins in The Army Game.

He never attained star status but created a gallery of sparky characters, including minor villains, servicemen, reporters and tradesmen enriched by an ever-present cheeky smile and an authentic cockney accent. He was Smudge or Smiley, Nipper or Knocker, Bert or ‘Orace, as part of an essential background – an everyman for every occasion.

It was Fowler’s authenticity that led to his break, as he explained to the film historian Brian McFarlane. Born in Lambeth, south London, as a “near illiterate newspaper boy” earning eight shillings a week, he was invited on to radio to tell of his life in wartime London. The broadcast was heard by film company executives who were looking for a Londoner to feature in a film about evacuees. He was screentested at Elstree studios and offered a monumental £5 a day to play opposite the only slightly less green George Cole.

Although he was later called up and served in the RAF, he appeared in the meantime in eight films, including Alberto Cavalcanti’s anti-fascist Went the Day Well? (1942), then again as an evacuee in The Demi-Paradise (1943). He was also in the modest semi-documentary Painted Boats in 1945, directed by Charles Crichton, whose next project was the timeless Hue and Cry.

Aged 21, Fowler was brilliantly cast below his years as the leader of a gang of south London kids who discover that their favourite blood-and-thunder magazine is being used by crooks to send coded messages about future robberies. The improbable story was enhanced by a memorable use of bombsites and fine performances, notably by Warner, cast against type as the villain, and a spooky Alastair Sim as the magazine’s duped author – plus the ebullient Fowler leading his gang and hundreds of boys and girls in the film’s rousing climax.

From then on Fowler worked steadily in the booming postwar film industry in films ranging from B-movies such as Top of the Form (1953) to The Longest Day and Lawrence of Arabia (both 1962). He regretted that British cinema seldom offered working-class characters “any intellectual horizons or heroic status”, although he was nudged towards this in the drama I Believe in You (1952).

Taking Warner at his word, he took any role offered in long-forgotten films such as The Dark Man (1951), alongside bigger productions including the Boulting Brothers’ pseudo-documentary High Treason (1951). He appeared in Cavalcanti’s Champagne Charlie (1944) and For Them That Trespass (1949), along with Joan Dowling, who had featured in Hue and Cry. She and Fowler were married in 1951. She took her own life in 1954 after her career faltered.

His career, meanwhile, benefited from his role as a jaunty Sam Weller in The Pickwick Papers (1952), which, although regarded critically as inferior to the earlier Great Expectations and Oliver Twist, was still a commercial hit. He also enjoyed the plum role of Hooker in I Believe in You (1952). As an under-privileged youngster, victimised by his stepfather, he was at the centre of the film, which was concerned with the probation service. He was even allowed romantic interest with Joan Collins but lost out to a brasher Laurence Harvey.

During the same period Fowler could be seen in series such as Dixon of Dock Green and Z-Cars, but his big television break came with three years’ duty in Granada’s popular comedy The Army Game (1959-61) and later as Harry Danvers in the heaven-sent Our Man at St Mark’s (1965-66). These and later series including World’s End (1981) and Dead Ernest (1982) brought lucrative employment, as did commercials.

He still accepted cameo roles in films, including Doctor in Clover (1966), recalling the advice that “each appearance was an advertisement for the next”. He turned up as a milkman delivering to a home tyrannised by Bette Davis in Seth Holt’s fine chiller The Nanny (1965), drove a cab in Lucky Jim (1957), and featured in the film of George and Mildred (1980), as he had in the TV series.

In farce he played an amiable sidekick to Hugh Griffith in the cult Start the Revolution Without Me (1970) and was in the costume drama Prince and the Pauper (1977) and then Fanny Hill (1983), as a beggar. He was last seen in cinemas in Body Contact (1987) and the dismal Chicago Joe and the Showgirl (1990), but worked on in television, appearing in The Bill, Doctor Who, Casualty, In Sickness and in Health and other series, and featured on radio in reminiscences of VE Day and postwar British cinema.

Fowler also participated in two documentaries about Diana Dors, a friend since they worked together on the engaging Dance Hall (1950), and in films about Dick Emery and Sid James, in the Heroes of Comedy series, both 2002. He also appeared in The Impressionable Jon Culshaw in 2004, still advertising for the next role…

He was appointed MBE in 1970. His second wife, Kay, survives him.

• Henry James Fowler, actor, born 10 December 1926; died 4 January 2012

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here