Joyce Carey obituary in “The Independent”.

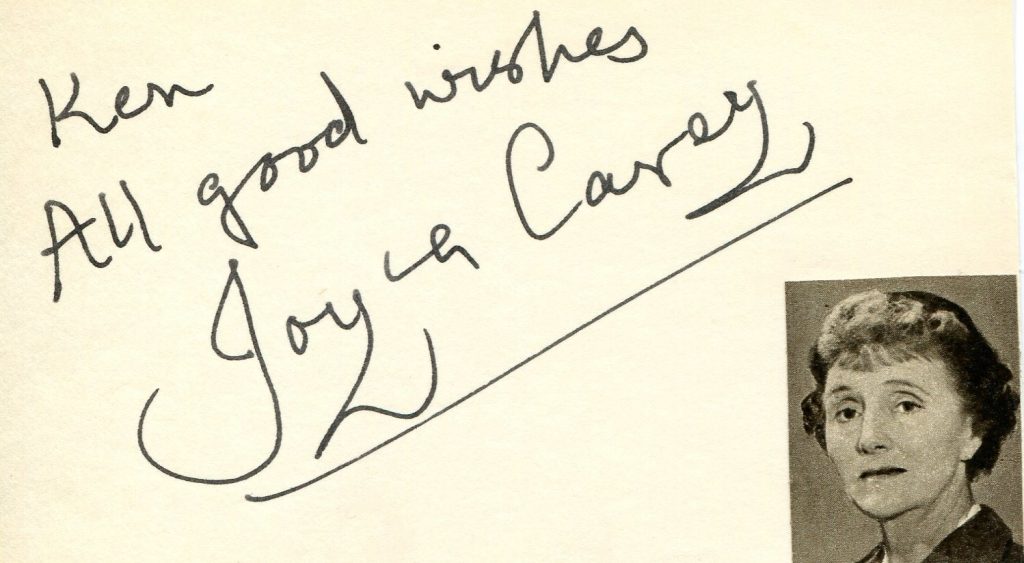

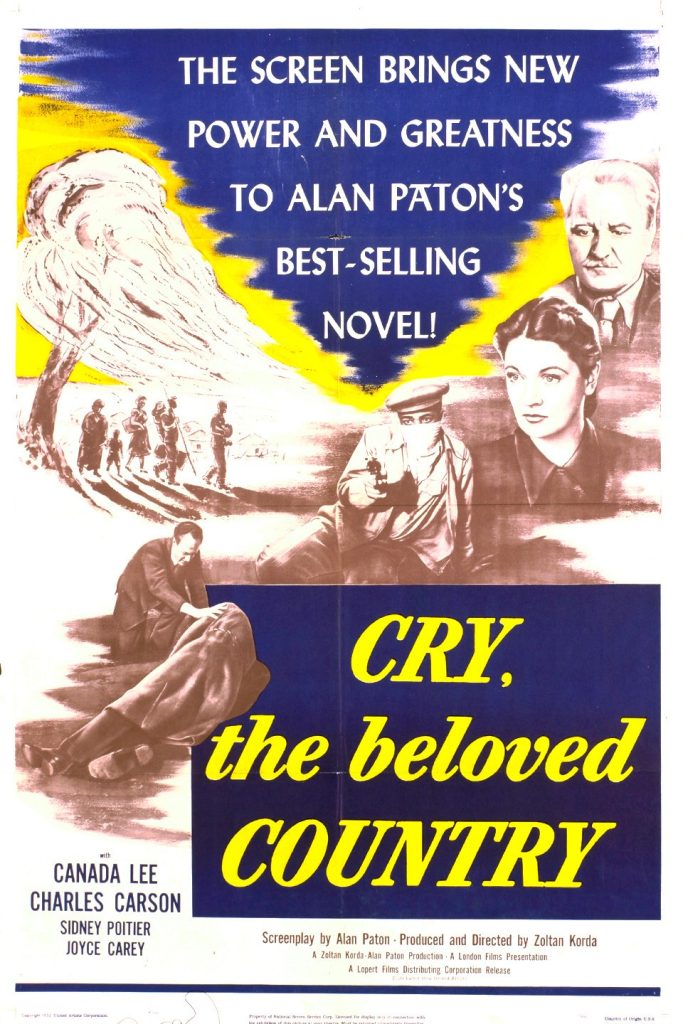

Joyce Carey was born in 1898. She was the daughter of actress Lilian Braithwaite. She is mostly associated with her performances in the works of Noel Coward. Her films include “In Which We Serve” in 1942, “Brief Encounter”, “Blithe Spirit” and “Cry, the Beloved Country”. She died in 1993.

Adam Benedick’s obituary in “The Independent”:Joyce Carey, actress, born London 30 March 1898, OBE 1982, died London 28 February 1993.

JOYCE CAREY was the last authoritative and closely human link with the world of Noel Coward and Binkie Beaumont in its pre-war heyday and wartime triumphs.

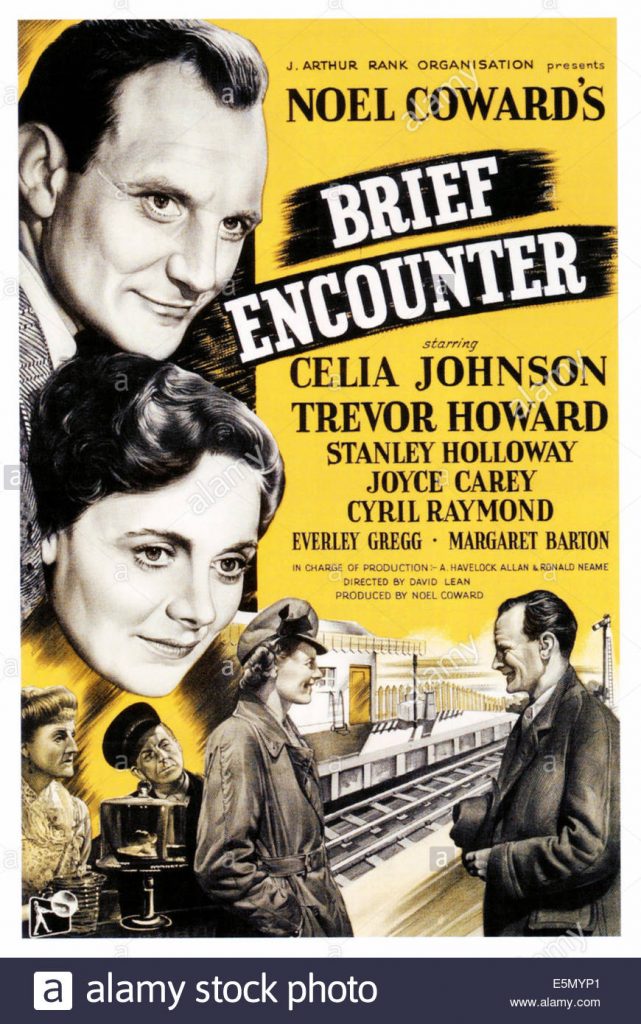

A slight, diminutive, graceful actress with a dry sense of comedy who specialised in managing wives and confidential aunts, twittering spinsters and sympathetic mothers – frowning at the antics of modern actors in light comedy as she surely had a right to, having first acted for the prince of light comedians, George Alexander, at the St James’s – she almost spanned the century in her service to the stage. It was a service of some influence. Not only as one of the busiest and most attractive players of her generation – starting in 1916 and more or less stopping in 1990 – but also as one of Coward’s loyalest friends and most constant companions. She was an invaluable actress in most of his plays and many of his films, including an unforgettably genteel barmaid in the station buffet in Brief Encounter (1945), suffering with skilful tact the advances of Stanley Holloway’s robust ticket collector.

‘Now look at my Banburys all over the floor,’ she gasped, polishing a tumbler after he had set her confectionery flying with one of his advances.

She was also an invaluable adviser behind the scenes and in the playhouse, where her tact and theatrical judgement shaped many a choice of cast and director. Who can wonder if her taste was so trusty? She had been born into one of the most illustrious theatrical families. Her father, Gerald Lawrence, was a notable Shakespearean who had acted for Irving; and her mother was to become Dame Lilian Braithwaite, a grande dame of the West End theatre for as long as anyone could remember, whose career achieved monumental status as a comedienne in the 1940s in the long-running Arsenic and Old Lace.

But 20 years earlier Lilian Braithwaite had formed the connection with Coward as his leading lady in his first hit as the spokesman of his generation – Florence Lancaster in The Vortex (1924). Almost from that moment onwards her daughter and Coward became friends, and the following year Joyce Carey played in Coward’s next piece, Easy Virtue, both in New York and in London. After which she spent the next seven years on Broadway or touring in the United States: not always in light comedies, sometimes in Shakespeare.

Joyce Carey had seen to it (under the influence of her parents) that her training should not ignore the classics; and having done a stint at Stratford-upon-Avon in 1919, she was often picked for West End Shakespeare revivals – as Jessica, Miranda, the Princess Katharine, Perdita or Celia (to Fabia Drake’s Rosalind); and on Broadway she turned up in The Elektra of Sophocles as Chrysothemis.

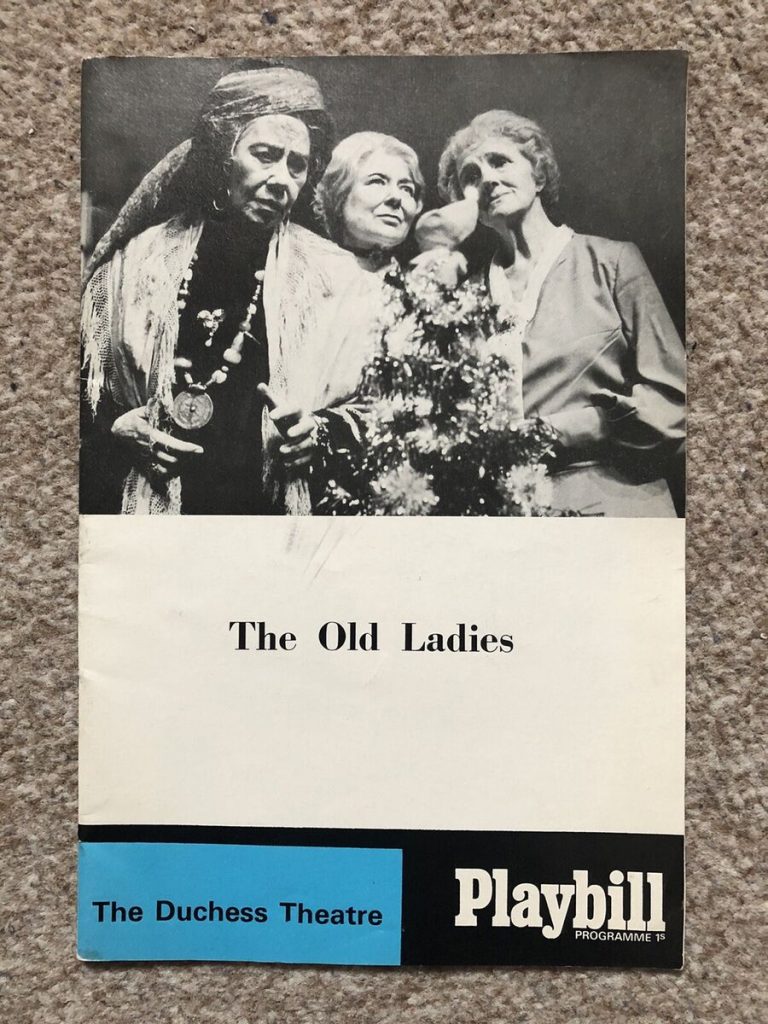

Indeed, years later she surprised her admirers by almost eclipsing her two rivals Joan Miller and Flora Robson in Peter Cotes’s 1969 production of The Old Ladies with her powerful expression of fear as the gentle May Beringer.

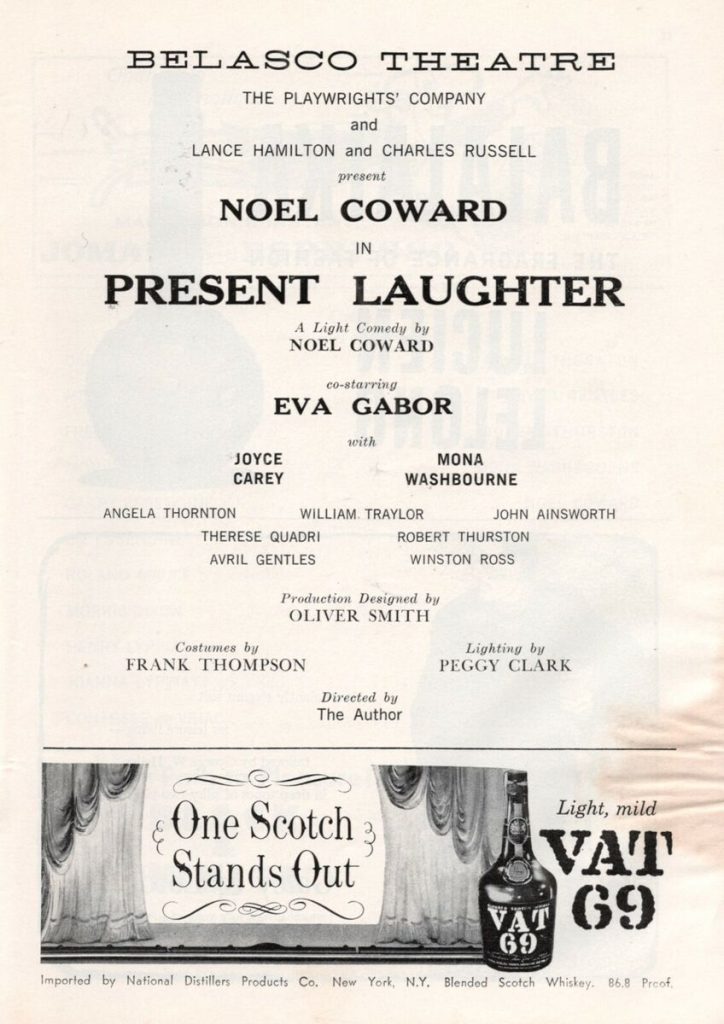

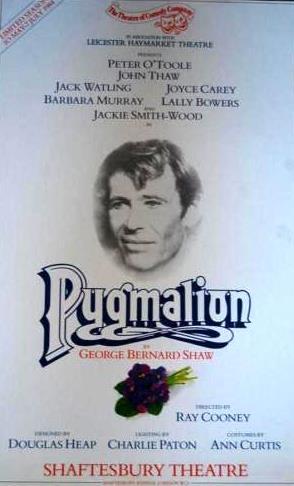

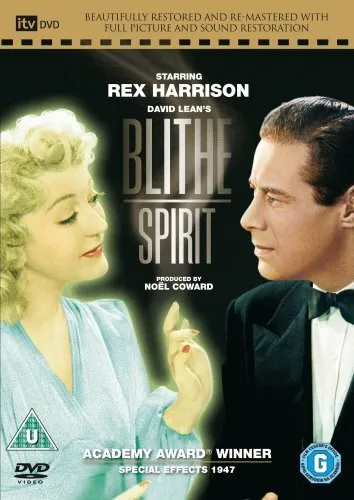

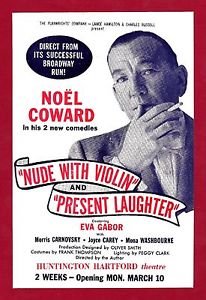

In general, though, Joyce Carey’s art flourished in comedy and particularly in Noel Coward’s branch of it, from the one-act plays comprising Tonight at 8.30 (1936) through wartime tours as Ruth in Blithe Spirit both for ENSA and the West End – where she also twice played Coward’s wife Liz Essendine in Present Laughter (1942 and 1947), and Sylvia in This Happy Breed, both at the Haymarket – before returning to Blithe Spirit for the last two years of its record-breaking run.

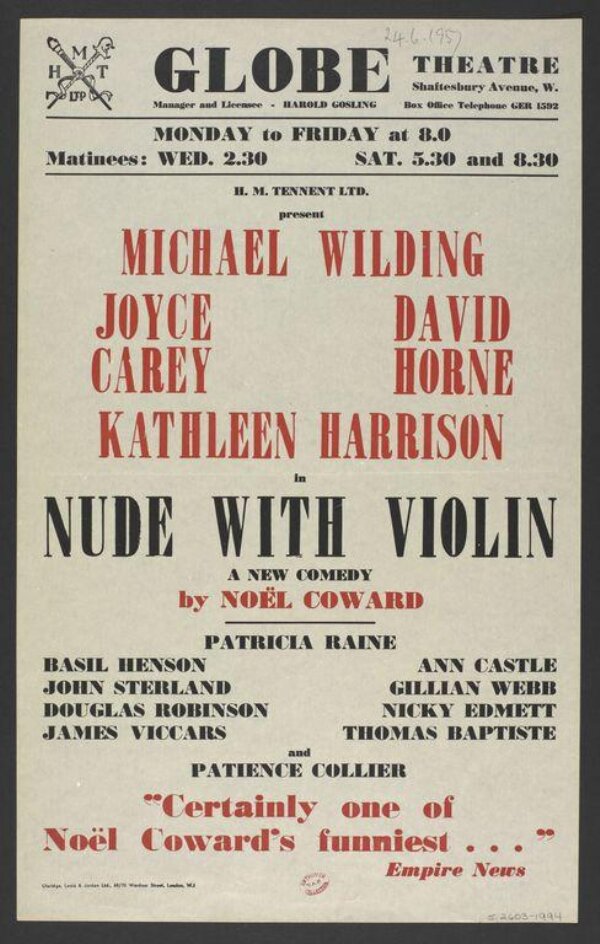

If Coward’s post-war plays had not much to offer her apart from Quadrille (with the Lunts), South Sea Bubble and Nude With Violin, Carey played Liz Essendine again on Broadway in 1958 and remained an important member of his entourage until his death in 1973. The entourage included, of course, the indomitable Beaumont, for decades the most powerful personality in the British theatre, who had given Carey her first chance as a playwright in the 1930s, and was now getting more anxious every minute about the changes taking place in post-war public taste.

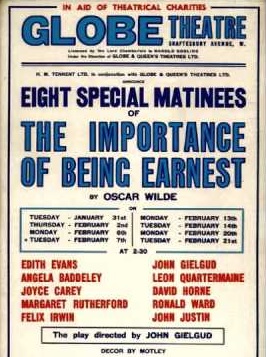

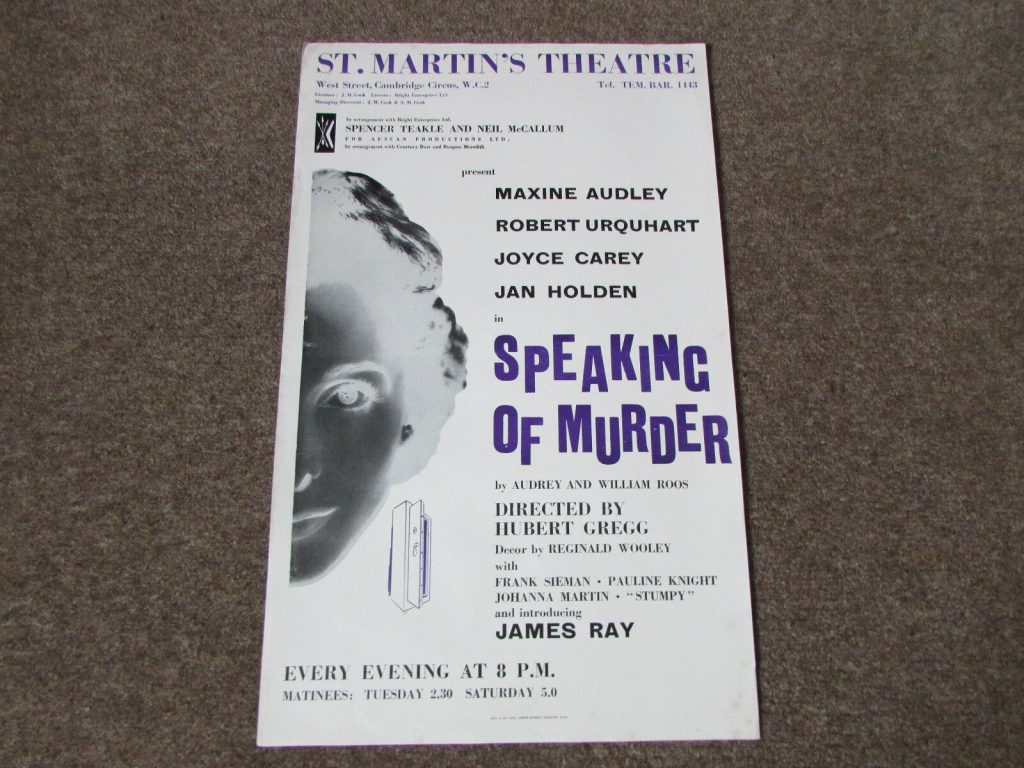

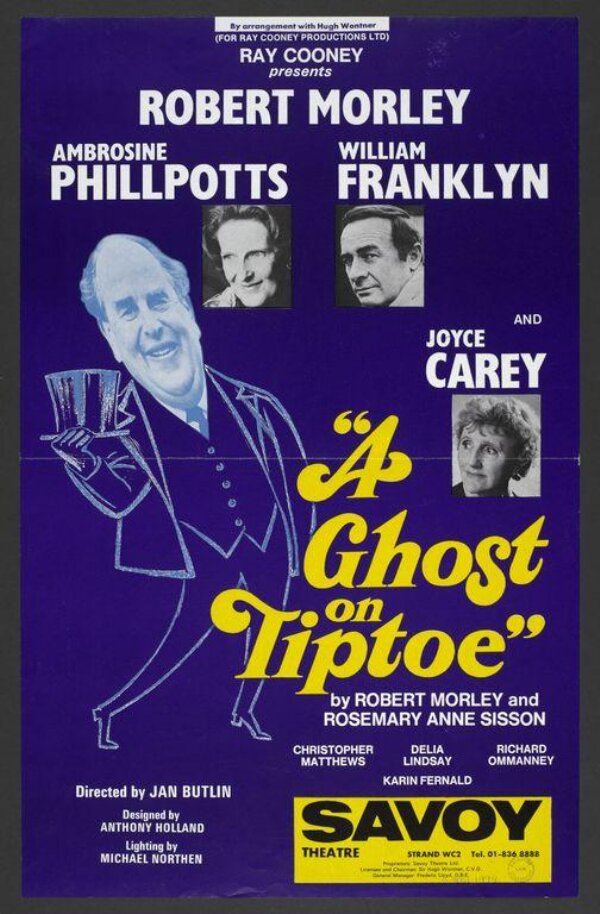

Carey was never fazed by such changes. If she had no truck with the kitchen-sink drama she could count on a regular need for her style of ladylike comedy; and there were still plenty of ladies in the old-fashioned sense to be acted in the plays of Wilde, Dodie Smith, Pinero and Agatha Christie in which she could quietly express her dignity, wit and social authority.

This may never have matched her mother’s but it assured playgoers who still had a taste for that sort of thing of the status of the West End drawing-room.

Her own play had been written under the pseudonym of J. Mallory, called Sweet Aloes, which had a year’s run at Wyndham’s in 1934 and was a well-crafted if novelettish weepie with aristocrats getting girls ‘into trouble’. Tyrone Guthrie directed it for Beaumont in London and in New York and she herself took on the role of Lady Farrington in both cities. In New York the play nudged Rex Harrison’s career forward.

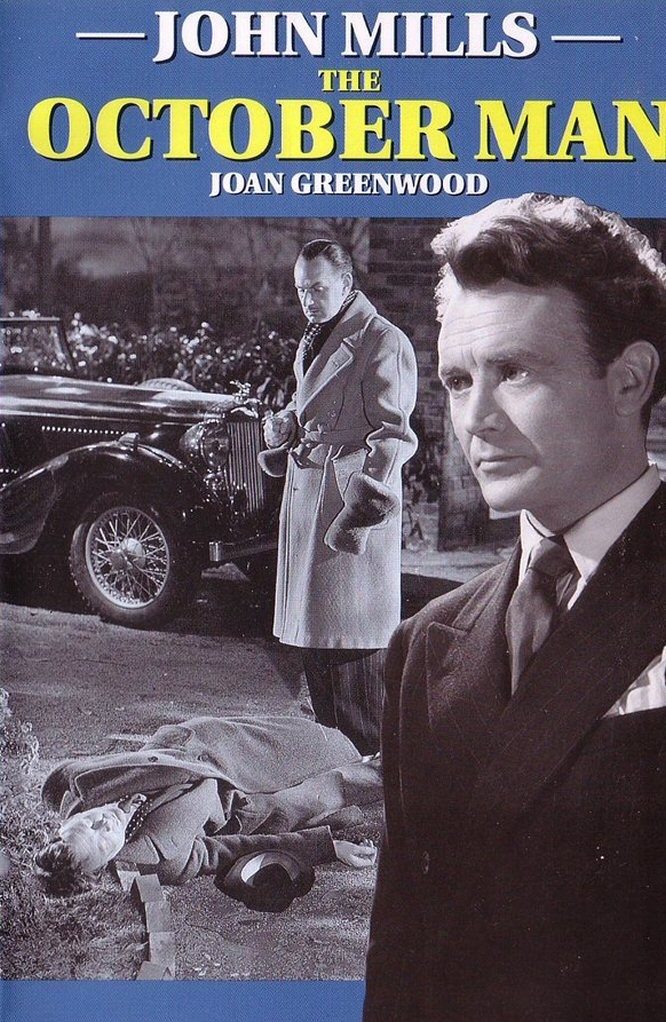

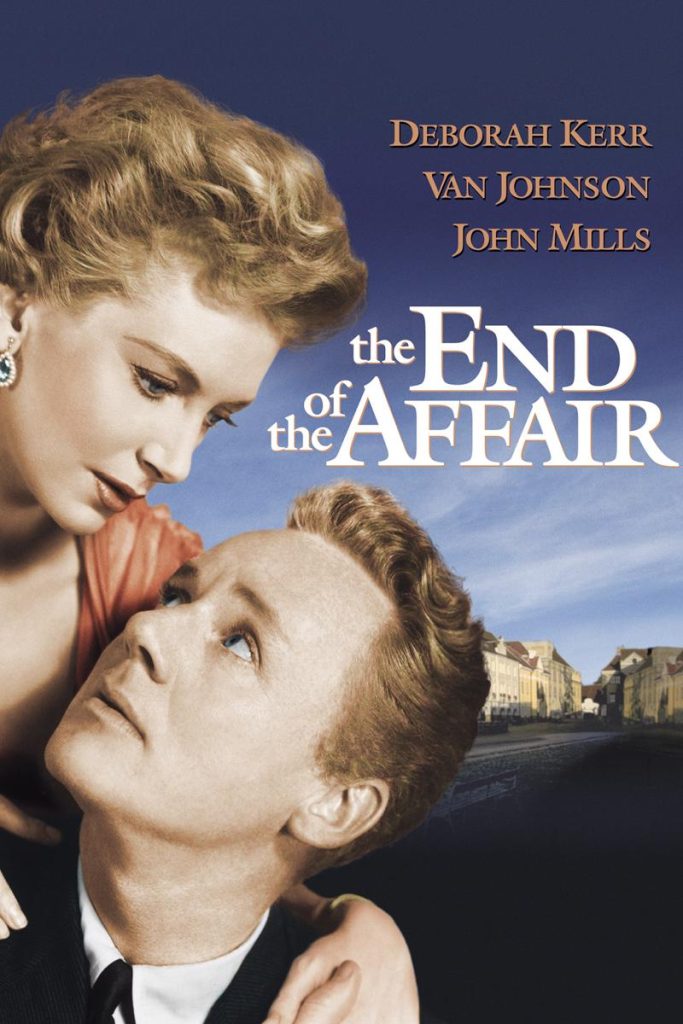

Apart from Brief Encounter, where that brief encounter with Stanley Holloway so pleasingly offset the gravity of the principals, her films, which had begun with silents in 1921, again reflected her affinity for Coward, including In Which We Serve (1942), Blithe Spirit (1945) and The Astonished Heart (1949), The Way To The Stars (1945), London Belongs To Me (1948), The Chiltern Hundreds (1949) and The End of the Affair (1954) – all sound English stuff.

But what could have been sounder than her choice of authors for her last two appearances on the London stage at the age of 90? The first was in a forgotten (because censored) piece by Coward, Semi-Monde from the 1920s, and the second was a similarly neglected work by Terence Rattigan, A Tale of Two Cities.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.