Maureen Potter obituary in “The Guardian”.

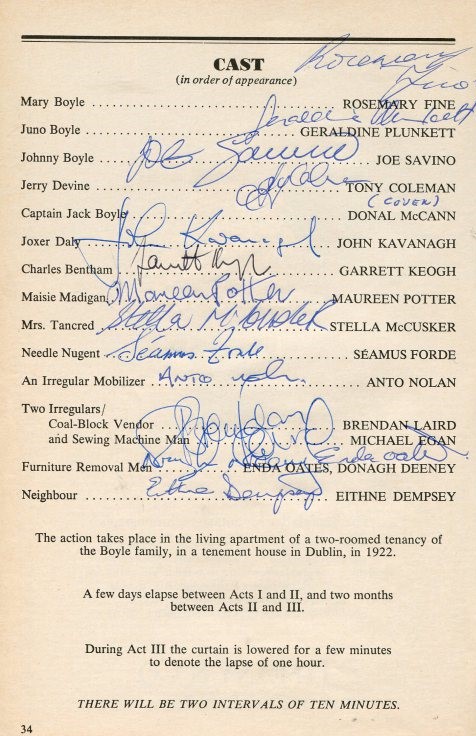

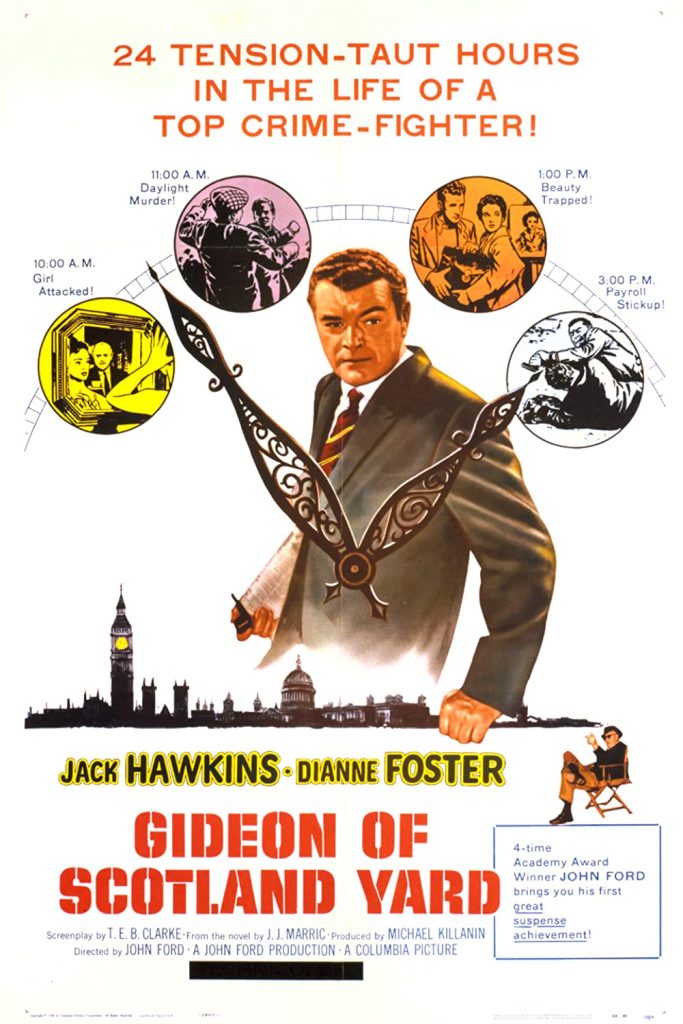

Maureen Potter was one of Ireland’s best loved performers. She was born in 1925 in Dublin. She was a popular child performer during the 1930’s. She had a long professional association with the actor Jimmy O’Dea and they spent several years in various touring shows with the occasional legit stage performance such as “Finian’s Rainbow”. In her later years she acted in dramatic roles such as “Juno and the Paycock”. Her few film performances include “The Rising of the Moon” in 1957, Gideon’s Day” and “Portrait of the Artist s A Young Man” in 1977. She died after a long illness in 2004.

Stephen Dixon’s “Guardian” obituary:Ireland’s best-loved entertainer, Maureen “Mo” Potter, who has died aged 79, enjoyed a 70-year career that embraced variety, pantomime, television, cinema and straight theatre. She was in the spotlight from the time she became the junior Irish dancing champion at the age of seven until ill-health forced her into retirement two years ago.

Billed as the Pocket Mimic, she toured Britain as a Shirley Temple impersonator with Jack Hylton’s band in the 1930s, alongside GH Elliott, Robb Wilton, the Crazy Gang, Hetty King and Wilson, and Keppel and Betty. She appeared at the London Palladium and, in 1938, performed in front of Hitler in Berlin. Enchanted by her performance, he sent her a handwritten note, which she proudly showed to her mother, who promptly threw it in the waste bin.

Potter stood just under 5ft in height, but there was nothing small about her personality and voice. Years of loneliness touring as a child – she borrowed a birth certificate because she was officially too young to work – made her appreciate her own fireside in Dublin, and she spent almost all her career in Ireland, in spite of overseas offers.

Born in the Dublin suburb of Fairview, she was discovered performing in local clubs by Ireland’s most popular comedian, Jimmy O’Dea, who put her in one of his pantomimes when she was 10. Two years later, she joined Hylton’s troupe.

After the war, she resumed a professional association with O’Dea that was to last for 30 years. Each epitomised the archetypal “Dub” – impoverished but resilient and proud, contemptuous of authority, and quick with the smart answer and the withering put-down – and they worked together brilliantly. Potter began as O’Dea’s “feed”, but, by the time of his death in 1965, the public saw her as her mentor’s equal.

She became the queen of pantomime at Dublin’s Gaiety theatre, most notably working with comedian and dancer Danny Cummins, and starred in a comedy show, Gaels Of Laughter, that ran for 15 summers. She was a fine singer and tap-dancer, but what captivated the public were her comic characters, like the exasperated mother of the 14-year-old Christy, and the Dublin “auld wan”, a version of the duologues she had performed with O’Dea as Dolores And Rose.

For generations of Irish children, Potter was an introduction to the magic world of theatre. In her pantomimes, she made a point of memorising the names of birthday children during the interval, then reeling them off in the second half without a prompt card – her record was 67. After the show, she would entertain them, drinking milk to set a good example, though with a tot of whiskey in it.

A woman of great sharpness, dignity and humility, Potter treated everyone she met – from the Taoiseach to Dublin street traders – with warmth and respect. Even the poet Patrick Kavanagh, as the grumpiest man in Dublin, once walked up to her and said: “Do you know what? You’re not a bad little woman at all.”

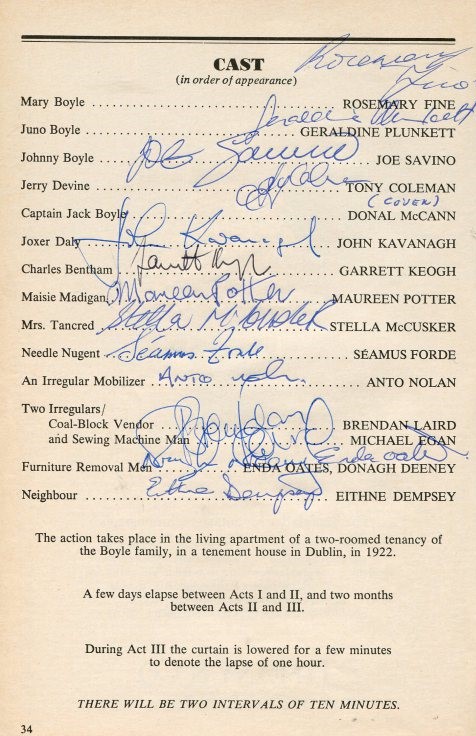

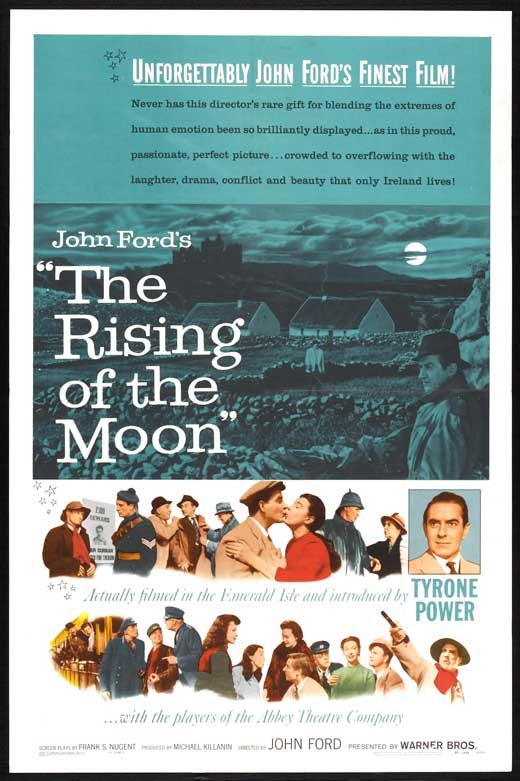

However, years of pratfalls and tap-dancing took a toll on Potter’s health, at a time when traditional variety was anyway in decline. So, with the adaptability of an old pro, she changed direction and became a straight actor. She appeared, to much acclaim, in several plays, notably at the Gate as Maisie Madigan in Sean O’Casey’s Juno And The Paycock (1986) – the production also had a New York run – and as Mrs Henderson in Shadow Of A Gunman (1996).

Potter was given the freedom of Dublin in 1984 and an honorary degree by Trinity College in 1988. In 1999, her life was celebrated at the Gaiety theatre, and, two years later, she became the first star to put her handprints in the theatre’s walk of fame. She made many television appearances in her later years, and wrote a series of children’s books.

In 1959, she married Jack O’Leary, an army officer she had known since 1943; she said she fell for him when she saw him, resplendent in his uniform, eating a bag of chips. The real reason probably involved a shared sense of humour, for O’Leary wrote most of Potter’s subsequent material. He, and their two sons, survive her.

· Maureen Potter, comedian, dancer and actor, born 1925; died April 7 2004

The above “Guardian” article can also be accessed online here.

Dictionary of Irish Biography:

Maureen

Contributed by

Potter, Maureen (1925–2004), variety artiste, comedian, and actress, was born Maria Philomena Potter (the baptising priest supposedly refused to countenance ‘Maureen’ as an acceptable Christian name) on 3 January 1925 at 7 St Joseph’s Terrace, Philipsburg Avenue, Fairview, Dublin, the only daughter among three children of James Benedict Potter, a commercial traveller, who died when Maureen was seven, and his wife Elizabeth (née Carr); Maureen was a fifth-generation Dubliner. Her mother was a talented singer, who shared a concert platform with John McCormack (qv) and Margaret Burke Sheridan (qv). Reluctant to commence her schooling, at age five Maureen agreed to attend her first day at St Mary’s national school, Fairview, on condition that she be allowed also to take dancing lessons. Duly enrolled in dancing classes locally, she proved remarkably talented, becoming at age seven all-Ireland junior dancing champion. Referred to the city-centre dance school of Connie Ryan on Abbey Street – the training school for juvenile dancing troupes who performed in the principal Dublin theatres – she soon was appearing in variety shows in Dublin and elsewhere. Throughout a sixty-year career in show business, dancing remained Potter’s first love.

CHILD STAR

While performing in the Star cinema stage show in Bray, Potter was scouted, on Ryan’s urging, by Jimmy O’Dea (qv), Ireland’s leading contemporary stage comedian, who placed her, at age ten, in his 1935 Christmas pantomime, ‘Jack and the beanstalk’, in Dublin’s Olympia theatre, as a fairy guarding the giant’s castle; with her precocious talent for mimickry, she also performed a sketch impersonating Dublin’s colourful lord mayor, Alfie Byrne(qv), costumed in miniature morning suit and stick-on moustache. After appearing in Dublin as the Pocket Mimic in the stage show of visiting English band leader and showman Jack Hylton, at age 12 she left school and toured with Hylton’s troupe throughout Britain and on the Continent (1937–9) – bearing a borrowed birth certificate because she was two years under Britain’s minimum legal working age – presented as a Shirley Temple impersonator, costumed and coiffed accordingly, an image that she loathed, and in later life remembered as totally incongruous with her features and physique. Making a huge impression while touring Germany in 1938 (owing to the novelty character there of child entertainers), she performed at the Scala theatre, Berlin, before the top Nazi leadership – including Hitler, Goering, and Goebbels – and was presented with a commemorative wreath; on her return to Dublin her mother angrily binned the memento, exclaiming ‘That filthy man, Hitler!’ (The likelihood that the incident occurred only after Potter’s returning to her Dublin home upon the British declaration of war in 1939 lends credence to what might otherwise be suspected as a revisionist recollection.)

PARTNERING O’DEA

Back in Dublin, Potter became a regular member of O’Dea’s company, appearing on the Dublin stage in his annual Christmas pantomimes and summer revues, and touring in variety theatres throughout Ireland and occasionally, after the war, in Britain. Successfully making the transition from child star to adult entertainer, Potter danced, sang, and performed verbal and physical comedy, moving swiftly from minor soubrette roles to regularly setting up O’Dea’s punch lines as his straight ‘feed’, becoming in time his comedy partner, working alongside him as a teamed equal, and allotted a solo or lead spot in every show. Her physicality suited comedy; a shade under five feet (1.52 m) in height, with a round, elfen face, and large, bulbous, twinkling eyes, she was a wren-like presence on the stage: tiny and rotund, darting hither and thither with restless energy, but with a massive speaking and singing voice that issued incongruously from the diminutive frame. Both she and O’Dea (who, at 5 ft 4 in (1.62 m), was as small a man as she was a woman) based their comedy to a large extent on playing the stereotypical working-class ‘Dub’: ‘impoverished but resilient and proud, contemptuous of authority, and quick with the smart answer and the withering put-down’ (Guardian, 13 April 2004). Potter’s recurring comic parts included the cheeky daughter of O’Dea’s most celebrated character, street-trader Biddy Mulligan, ‘the pride of the Coombe’; and Dolores, the ‘fur hur from Furview’, a young, impetuous, and ingenuous Dublin ‘wan’, in tandem with O’Dea’s faded and worldly-wise Rose.

STRAIGHT THEATRE

Though her forte was always pantomime and variety, Potter first played the legitimate stage for a period in the latter 1950s. She performed opposite Cyril Cusack (qv) in two plays at Dublin’s Gaiety theatre in 1956: a revival of ‘The golden cuckoo’ by Denis Johnston (qv), directed by the author, in which she made ‘an uproarious success of her first straight comedy part’ playing a charwoman ‘with itchy fingers and a tongue of vitriol’ (Irish Times, 26 June 1956); and as the Lion in ‘Androcles and the lion’ by George Bernard Shaw (qv). She joined a galaxy of Dublin comics (including O’Dea, Milo O’Shea (qv), Genevieve Lyons, and Aiden Grennell (1920–2001)) who supported Hilton Edwards (qv) in ‘The man who came to dinner’ (1957); playing the hyper-efficient, but love-struck, secretary of Edwards’s Sheridan Whiteside, she ‘subdue[d] her broader comedy gifts to emerge with a most efficiently controlled job of straight acting’ (Irish Times, 11 June 1957). She appeared with O’Dea in the first Irish production of the musical ‘Finian’s rainbow’ (1957); with Micheál MacLiammóir (qv) in his stage adaptation of ‘The informer’ (1958), from the novel by Liam O’Flaherty (qv); and in ‘Harvey’ (1959), the Pulitzer Prize winning comedy by Mary Chase. In Johnston’s ‘The dreaming dust’ (1959), she played Vanessa to Edwards’s Jonathan Swift (qv), as well as ‘a couple of neat Dublin character bits on the side’ (Irish Times, 22 September 1959).

Potter married (30 September 1959) John (‘Jack’) O’Leary , a career army officer three years her senior, whom she had known from the early 1940s; they had two sons, and resided in Clontarf. (Six days before her marriage, Potter had been bridesmaid at the wedding of the recently widowed O’Dea to Ursula Doyle.) Quiet and mild-mannered, with a dry humour, O’Leary complemented Potter’s high-strung ebullience. Hearing her rehearsing lines at home, he would suggest improvements, and eventually became her main scriptwriter, especially of her solo stage and radio sketches.

VARIETY HEADLINER

By the early 1960s Potter was headlining her own variety shows, while still working regularly with O’Dea. She appeared in his swansong, a Gaiety revival of ‘Finian’s rainbow’ (summer 1964). After O’Dea’s death (January 1965), Potter headlined the Gaiety’s annual pantomimes for the next two decades, supported for many years by comedian and singer Danny Cummins (1914–84), and in later years by Brendan Grace, Red Hurley, and others. Thus, from 1932, and on the Gaiety stage from 1939, till her retirement from the genre in 1986, Potter performed in Dublin pantomime in every Christmas season save two: when pregnant (1962/3), and during O’Dea’s terminal illness (1964/5). She described pantomime as her favourite professional activity, owing to ‘all those gleefully participative children’ (Irish Times, 8 April 2004), and named her favourite panto titles as ‘Tom Thumb’ and ‘The pied piper of Hamelin’, the latter because of the inclusion of children in the cast. She was renowned for an uncanny capacity to memorise long lists of names of individual children and groups in an audience, and acknowledge each from the stage before the final curtain. Further belying the actor’s proverbial wariness of performing with children and animals, as a confirmed animal lover (especially devoted to cats), she was obsessively solicitous of the welfare of animals employed in her stage shows (adamantly opposed to blood sports, especially hare coursing, she participated in protests on the issue). Her career having been launched at a time when pantomime was an essential part of most every child’s Christmas, and many a person’s first experience of live theatre, through her perennial skill and boundless enthusiasm for the genre, alongside her enduring personal popularity, Potter did much to preserve the viability of pantomime in Ireland, despite profound cultural changes and changing tastes in popular entertainment.

For fifteen years Potter headlined a series of summer revues at the Gaiety, ‘Gaels of laughter’ (1965–79), directed by O’Dea’s widow, Ursula Doyle, and supported by leading comedians and pop singers, including Milo O’Shea, David Kelly, Rosaleen Linehan, Des Keogh, and Hal Roach. She played the villainous Miss Hannigan in the Irish premiere of the musical ‘Annie’ (1980), her performance described as ‘an original comic creation of great merit, even if the star herself is too kindly a soul ever to strike fear’ (Irish Times, 19 July 1980). Her career seriously restricted by chronic health problems in the mid 1980s – she suffered from recurrent diverticulitis (bowel inflammation), requiring eventual surgery, and from arthritis in the hips and knees, resulting in joint replacements – she retired from pantomime, no longer able to undertake the vigorous dancing and pratfalling: ‘I couldn’t throw myself about any more’ (Irish Times, 26 November 1994).

STAGE ACTRESS

For several seasons in the 1980s–90s she starred in a popular one-woman cabaret show at Clontarf Castle, billed as the ‘Queen of Irish Comedy’; a recording of one such show was released on video (1994). Concentrating also on a return to the legitimate stage, she appeared with Siobhán McKenna (qv) – whose acting style had long been a subject of Potter’s parody – as the two sweetly murderous old ladies in a hit production of ‘Arsenic and old lace’ at the Gaiety (1985). Potter played Maisie Madigan in the Gate theatre production, directed by Joe Dowling, of ‘Juno and the Paycock’ by Sean O’Casey (qv), one of the most celebrated productions in recent Irish theatre history, opposite Donal McCann (qv), John Kavanagh, and Geraldine Plunkett (1986); she toured with the production to Jerusalem (1987) (where she was besieged by Irish-born Israelis who as children had seen her in Dublin pantos), Edinburgh (1987), and to especial acclaim in New York (1988) (where she was forced off her feet between shows by agonising knee pains, but never missed a date). Her performance, directed by Patrick Mason at the Gate, as Mrs Candour in ‘The school for scandal’ (1989) by Richard Brinsley Sheridan (qv) was praised as one of the highlights of the production. Less satisfying was her interpretation of Samuel Beckett (qv), in both ‘Footfalls’ and ‘Rockaby’ during the Gate’s Beckett festival (1991); critic Gerry Colgan found her performance ‘too vigorous’ and charged with ‘too much psychic energy’ for the material (Irish Times, 11 October 1991). Potter’s only career appearance at the Abbey theatre was in the premiere of ‘Moving’ (1992) by Hugh Leonard(qv). She played Mother in a revival of Leonard’s most famous play, ‘Da’ (1993), directed by Dowling at the Olympia, opposite McCann and Barnard Hughes (who reprised his Tony-award-winning performance in the title role). She was directed, as Mme Pernelle, by Alan Stanford in a new version by Michael West of Molière’s ‘Tartuffe’ (1992), and returned to O’Casey as Mrs Henderson in ‘The shadow of a gunman’ at the Gate (1996).

OTHER MEDIA

Though primarily a stage performer, Potter appeared on radio, television, and in several films. During the 1940s she was a frequent guest, with O’Dea as host, on Irish half hour, a BBC radio light entertainment programme. For seven seasons she hosted a popular Radio Éireann variety programme, The Maureen Potter show (1960–67), which included comic sketches and monologues, and mild political satire (usually involving Potter’s impersonating politicians); especially beloved by the public were her ‘Christy’ monologues, in which she played the ever solicitous, harried mother of a naughty Dublin child prone to improbable scrapes. She appeared as the storyteller in several episodes of the long-running BBC television children’s programme Jackanory (1966), and co-starred alongside Rosaleen Linehan as two man-mad flatmates in Me and my friend (1967), one of RTÉ television’s first situation comedy series, directed by Jim Fitzgerald (qv). Potter’s Christmas television special topped the RTÉ TAM ratings in 1973. She acted in two films directed by John Ford (qv): The rising of the moon (1957), a triptych in which she played the railway station barmaid in the second segment, ‘A minute’s wait’ (the ensemble cast included O’Dea as the station porter); and Gideon’s day (1958). She was cast by director Joseph Strick in two adaptations of works by James Joyce (qv): in Ulysses (1967) she played Josie Breen, an old flame of Leopold Bloom (played by Milo O’Shea); she played Dante in A portrait of the artist as a young man (1977), opposite T. P. McKenna (1929–2011) as Mr Dedalus, Rosaleen Linehan as Mrs Dedalus, and Desmond Perry as Mr Casey. Her final film was Graham Jones’s How to cheat in the leaving certificate (1997).

HONOURS

Potter wrote a children’s book, The theatre cat (1986; reissued as Tommy the theatre cat (1989)). She was accorded a special tribute programme of RTÉ television’s Late, late show (1976); was granted the freedom of the city of Dublin (1984); was awarded an honorary degree by TCD (1988); and received a special Harvey’s Irish Theatre Award for services to the Irish theatre (1988). A documentary recounting her career, Super trouper, directed by John McColgan, and including archival performance footage, aired on RTÉ television (1994), and an eight-part retrospective series, Maureen Potter looks back, was broadcast on RTÉ radio (1998). The Gaiety theatre staged a special celebration of her life, attended by President Mary McAleese and leading figures in Irish theatre and entertainment (1999). Potter was the first person invited to place her handprints in the walk of fame constructed in the pavement outside the Gaiety theatre (2001).

ASSESSMENT

An audience favourite over many decades, Potter was perhaps the most popular entertainer of twentieth-century Ireland, with an appeal that crossed generations, social class, and the urban/rural divide, likely seen by more people on the live stage than any other performing artist in the country. The notoriously curmudgeonly poet Patrick Kavanagh (qv) once approached her on a Dublin street and said: ‘Do you know what? You’re not a bad little woman at all’ (Guardian, 13 April 2004). The consummate variety performer, with a masterly command of comic timing, and a stage presence exuding enthusiasm and delight, she also proved adept at acting comic roles in straight theatre; amplifying on the stage adage about comedy being more difficult than tragedy, Potter added that ‘it’s much harder for a comic to do comedy in a straight play’ (Irish Times, 26 September 1985). While reviewers sometimes found her variety shows to be uneven in quality, formulaic, and repetitive, rarely were Potter’s skills as a performer disparaged, the critique usually being that she was burdened with scripts (or with co-stars) unworthy of her talents. Notwithstanding her long experience and audience adulation, she suffered severely from nerves before every performance, sometimes to the point of physical sickness, a condition that only worsened as she aged.

Widely admired by her peers within the theatrical profession, Potter was remembered for her loyalty, consideration, lack of conceit, generosity, and boundless good humour (which never flagged through years of pain and illness). Her favourite recreation was watching television sport, especially soccer and cricket. Down the years she closed performances with a signature closing line: ‘If you liked the show tell your friends; if you didn’t, keep your breath to cool your porridge’.

Potter died 7 April 2004 in her Dublin home; the funeral was from St Brigid’s Roman catholic church, Killester, to Clontarf cemetery.

Sources

GRO (b. cert.); Ir. Times, passim, esp.: 26 June, 3 July 1956; 11 June, 9 July 1957; 11 Nov. 1958; 9 June, 22, 25 Sept., 1 Oct. 1959; 25–7 Dec. 1962; 23, 24 July 1964; 3 Mar., 28 June 1966; 4 July, 23 Nov. 1967; 18 June 1970; 10 July 1975; 2 Aug. 1979; 19 July 1980; 14 June, 26 Sept., 2 Oct. 1985; 11, 16, 17 July 1986; 12 June, 13 Aug. 1987; 23 June, 12, 24 (profile) Dec. 1988; 26, 29 July 1989; 29 Aug. 1990; 7, 28 Sept., 11 Oct. 1991; 7 Oct., 16 Dec. 1992; 12 Mar. 1993; 26 Nov. 1994; 17, 30 July 1996; 4 June 1998 (profile); 16, 19 Jan. 1999; 8, 10 Apr. 2004; Philip B. Ryan, Jimmy O’Dea: the pride of the Coombe (1990); Micheál Ó hAodha, Siobhán: a memoir of an actress (1994); Times, 8 Apr. 2004; Sunday Independent, Sunday Tribune, 11 Apr. 2004; Guardian, 13 Apr. 2004 (www.guardian.co.uk/news/2004/apr/13/guardianobituaries.artsobituaries1); Independent (London), 13 Apr. 2004 (www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/maureen-potter-549747.html); Deirdre Purcell (ed.), Be delighted: a tribute to Maureen Potter (2004); Internet Movie Database, www.imdb.com; Irish Film & TV Research Online, www.tcd.ie/irishfilm; Irish Playography, www.irishplayography.com (websites accessed March 2011