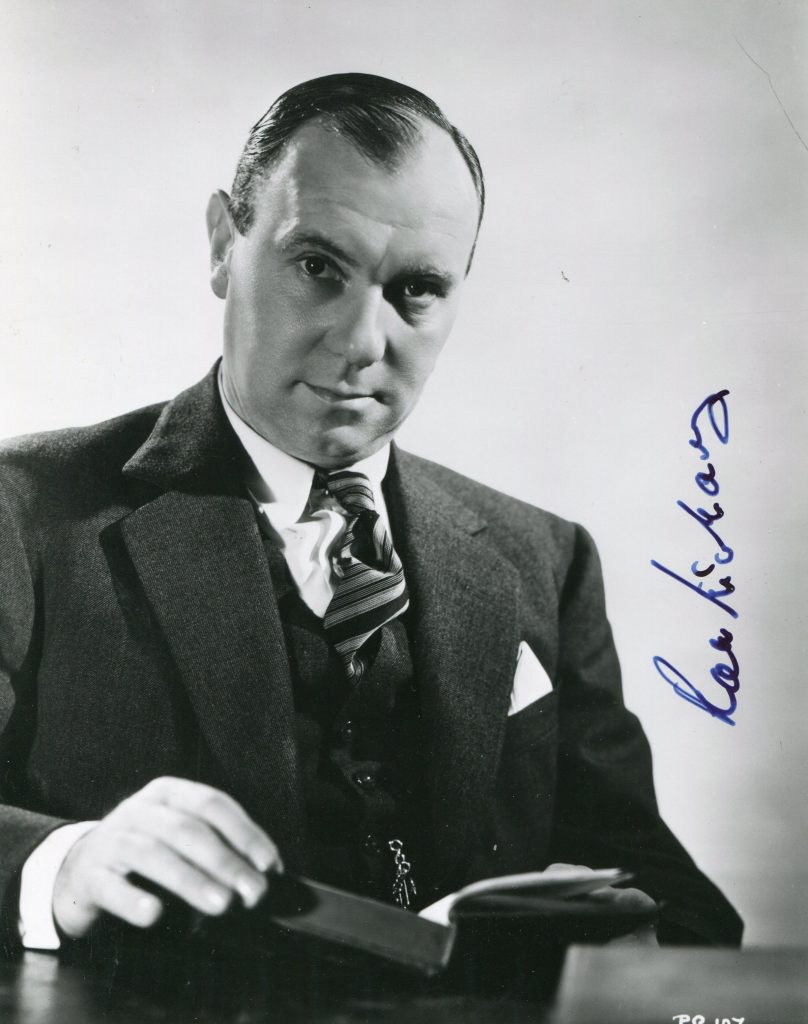

Sir Ralph Richardson was most of that select group of English actors who became ‘knights of the realm’ and made major contributions to British theatre and film in the mid 20th Century. The group included Laurence Oliver,John Gielgud, Michael Redgrave and Alec Guinness. He was born in 1902 in Chelteham. In 1925 he joined Barry Jackson’s famed Birmingham Repertory Company. During the years of World War Two, he and Laurence Oliver had some major triumphs on stage at the ‘Old Vic’ in London. Richardson won widespread critical acclaim for his roles in “Uncle Vanya” and “An Inspector Calls”. His first film was “The Ghoul” in 1933 and his most noteworthy movies include “The Four Feathers” in 1939, “The Fallen Idol”, !”The Heiress” and “Doctor Zhivago”. He was a keen motor biker and rode his machine until e was in his late 70’s. He died in 1983.

ile on TCM:

Described by the Times of London as “equipped to make an ordinary character seem extraordinary, or an extraordinary one seem ordinary,” Sir Ralph Richardson was one of the most celebrated British actors of the 20th century. He regularly brought humor and humanity to every role he played, from unsympathetic fathers in “The Heiress” (1949) and “Long Day’s Journey Into Night” (1962) to nearly every great Shakespearean role and even playing God in Terry Gilliam’s “Time Bandits” (1981). A friend and frequent collaborator with the three great “knights” of the English acting profession – Lord Laurence Olivier, Sir John Gielgud and Sir Alec Guinness – Richardson joined them in their domination of the stage in the 1940s and 1950s. And if his film career was not as celebrated as that of Olivier or Guinness, he rarely endured bad films or overwhelming critical expectations. Viewers knew that Richardson would deliver a quietly mesmerizing performance every time he appeared on stage or screen, capturing attentions through carefully considered gestures and inflections. In doing so, he remained a presence in films from the late 1930s until the early 1980s, when he received a posthumous Oscar nomination as the Earl of Greystoke in “Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes” (1984). A gently eccentric but extraordinarily focused actor, he was also endearingly self-effacing, once describing the secret of his acting talent as “the art of keeping a large group of people from coughing.” His accomplishments as an actor remained the high water mark for his profession after nearly six decades.

Born Ralph David Richardson in the borough of Cheltenham, in Gloucestershire, England, on Dec. 19, 1902, he was the son of Arthur Richardson, an art teacher at Cheltenham Ladies’ College, and his wife, Lydia Russell. Richardson’s mother left his father when their son was still a baby, and she raised him in a series of homes in nearby Gloucester and other towns. He spent much of his childhood alone, and amused himself through play-acting, which spurred his interest in the theater. However, both parents had distinct ideas about Richardson’s career path; his father hoped that he would take up art, while Russell wanted him to become a priest. But after brief tenures at both art school and a Jesuit seminary, he took his inheritance of 500 pounds from a grandmother and auditioned for a theater company in Brighton. The tryout went poorly, and Richardson was forced to pay 10 shillings a week to remain in the company. He was initially put in charge of the sound props, but bungled the job badly.

But after a year’s time, he showed enough promise as an actor to graduate from walk-on roles to minor speaking parts and eventually, supporting and lead characters. He joined a Shakespearean repertory company and toured the United Kingdom for five seasons before joining the esteemed Birmingham Repertory Company, which counted Laurence Olivier, Paul Scofield and Derek Jacobi among its later members. In 1926, he made his London stage debut in “Oedipus at Colonus,” which was soon followed by his West End debut in “Yellow Sands,” which co-starred his wife, actress Muriel Hewitt. Richardson’s stage career hit its stride after he joined the Old Vic Theatre for two seasons; there, he performed with John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier in celebrated productions of Shakespeare’s plays, which resulted in a lifelong friendship between the three men.

Richardson made his feature film debut in “The Ghoul” (1933), an atmospheric British horror film with Boris Karloff as a mystic who appeared to return from the grave, and Richardson as a seemingly harmless local vicar. By this point in his career, he was well established as one of the leading performers of the world stage, thanks to a series of acclaimed turns in W. Somerset Maugham’s “Sheppy,” the 1934 production of “Romeo and Juliet,” for which he replaced Orson Welles as Mercutio, and Barre Lyndon’s “The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse,” which ran for 492 performances in 1936. That same year, he signed a multi-picture deal with producer Alexander Korda, which resulted in several classic films. In William Cameron Menzies’ adaptation of “The Shape of Things to Come” (1936), he was “The Boss,” a brutal, petty warlord who rose to power in the wake of global devastation, while in the Technicolor comedy “The Divorce of Lady X” (1938), he played a school friend of Laurence Olivier, who was convinced that the woman he had fallen in love with (Merle Oberon) was Richardson’s wife. And in the epic adventure The Four Feathers (1939), he gave one of the title objects, a sign of cowardice, to British officer John Clements, who in turn saved Richardson’s life in battle against the Sudanese. Richardson earned his first lead in “On the Night of the Fire” (1939), a dark drama about a town barber whose impulsive theft of 100 pounds led to devastating personal ruin.

During WWII, Richardson joined Olivier in the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Volunteer Reserve, where he rose to the rank of lieutenant commander. The period was an emotionally devastating one for him; not only had his wife succumbed to sleeping sickness in 1942, but the Old Vic had been badly damaged during the German bombing raids on London. Both Richardson and Olivier were released early in 1944 to take over the company with director John Burrell. There, Richardson delivered what many would consider his finest performance, including Falstaff in a 1945 production of “Henry IV” and the title role in “Peer Gynt.” His tenure at the head of the Old Vic was regarded as the greatest period in the theater’s history – an opinion not shared by its board of governors, who sacked him and Olivier over fears that their popularity would overshadow that of the theater itself.

In 1947, Richardson was knighted for his contributions to the British theater. The following year, he appeared as Alexei Karenina, whose chilly relationship with his wife, Anna (Vivien Leigh) drove her to infidelity in the Korda-produced adaptation of Anna Karenina (1948). It preceded an acclaimed period in Richardson’s film career, which included Carol Reed’s The Fallen Idol (1948), which provided him with one of his best film roles as a butler whose young charge (Bobby Henrey) accidentally implicated him in his wife’s death. In 1949, he made his Hollywood film debut in William Wyler’s “The Heiress” (1949), for which he repeated his role from the stage production as Olivia de Havilland’s emotionally distant father, who bullied her into rejecting her suitor (Montgomery Clift). Richardson earned an Oscar nomination for his performance, as well as the National Board of Review’s award for best actor.

Richardson’s stage career took something of a downward turn in the early 1950s, with critically savaged turns in “The Tempest” and a Gielgud-directed “Macbeth.” He also turned down the chance to appear in the English-language debut of Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot,” a decision he regretted for the rest of his career. Greater success was found in feature films, most notably in “Breaking the Sound Barrier” (1952), Carol Reed’s drama about a wealthy airplane designer whose single-minded drive to conquer the sound barrier resulted in the death of his daughter’s husband (Nigel Patrick). Richardson won his second National Board of Review Award for his stern performance, as well as the BAFTA and the New York Film Critics Award, but not the Oscar, as nearly all NYFC winners had done. Other superior film roles during this period came in “The Holly and the Ivy” (1952) as a clergyman who devoted more attention to his parish than his family, and as the corrupt Duke of Buckingham in Olivier’s celebrated 1955 film version of “Richard III.”

Richardson’s stage career rebounded in the late 1950s with acclaimed turns in “The Flowering Cherry” in London and “The Waltz of the Toreadors” on Broadway, which brought him a Tony nomination. He also settled into a string of character turns in Hollywood and British features, most notably as the mysterious operative “C” in Reed’s “Our Man in Havana” (1959) and an English general overseeing a Jewish internment camp in “Exodus” (1960). In 1962, he received one of his best screen roles as the miserly ex-actor and patriarch in Sidney Lumet’s adaptation of “Long Day’s Journey into Night” (1962). Abetted by Katherine Hepburn, as well as Jason Robards – the leading interpreter of O’Neill on the American stage – and Dean Stockwell, Richardson gave a searing portrait of a man no longer able to abide reality, who has descended into drink and dissolution. He and each of his castmates were each rewarded with the Best Actor and Actress Awards at the 1962 Cannes Film Festival, and he soon followed it with a string of expert turns in historical epics like “The 300 Spartans” (1962) for Rudolph Mate, and “Woman of Straw” (1964), Basil Dearden’s tense British noir with Sean Connery and Gina Lollobrigida as scheming lovers who plan to murder Connery’s cruel uncle (Richardson). In 1965, he played Sasha Gromeko, the kindly medical professor who took Omar Sharif under his wing in David Lean’s epic “Doctor Zhivago” (1965).

After “Zhivago,” Richardson devoted more time to rebuilding his stage career than on screen, and his ’60s era features were relegated to small but notable supporting turns as government officials in “Khartoum” (1966), opposite Olivier and Charlton Heston, “The Battle of Britain” (1969), and the espionage thriller The Looking Glass War (1969), based on a novel by John le Carre. He also appeared in the black comedy The Wrong Box (1966) alongside Peter Sellers, Dudley Moore, Peter Cook, John Mills and Michael Caine and in Spike Milligan’s surreal anti-war film, “The Bed-Sitting Room” (1969), as an English lord who transformed, due to nuclear fallout, into the title room. The stage continued to be his greatest showcase, and he proved his mastery of the art in the 1960s in productions of Pirandello’s “Six Characters in Search of an Author” and the original 1969 production of Joe Orton’s controversial “What the Butler Saw” as a doctor overseeing an outbreak of sexual hysteria at a psychiatrist’s office. He also teamed with Gielgud in “Home” (1970), which was filmed for broadcast on the BBC series “Play for Today” (1970-1984). The TV version was historic in that it was the sole recording of Richardson’s monumental work on stage. The pair later appeared together in Harold Pinter’s “No Man’s Land,” which, like “Home,” traveled to Broadway for a successful run.

Richardson became remarkably active on film and in television during the 1970s at an age when most actors would consider a slower pace. In interviews, he stated that he could not afford to retire, not for financial reasons, but to sate his own boundless curiosity about his fellow man. There were oddities along the way, like a turn as the malevolent Crypt Keeper in the 1972 horror anthology “Tales from the Crypt,” and as the Caterpillar in a 1972 adaptation of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.” But he lent considerable charm and wisdom to offbeat films like Lindsay Anderson’s “O Lucky Man!” (1973) and “Rollerball” (1975), and brought the weight of his theater experience to a little-seen production of “A Doll’s House” (1975) with Anthony Hopkins. He also appeared alongside nearly every leading English actor, including Olivier, James Mason, Peter Ustinov, Ian Holm, Ian McShane and Michael York in “Jesus of Nazareth” (NBC, 1977).

Richardson’s career eventually wound down on a positive note. After appearing as an ancient wizard in the costly, Disney-produced fantasy “Dragonslayer” (1981), he gave a charming comic performance as a disinterested Supreme Being in Terry Gilliam’s “Time Bandits.” He then filmed his final screen appearances – as a mysterious and possibly supernatural old man in the Paul McCartney vanity project, “Give My Regards to Broadstreet” (1984) and then as the aged Earl of Greystoke in “Greystoke” The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes.” Richardson’s warm and thoughtful performance was the high point of the latter film, which introduced audiences to Christopher Lambert. The stage was never very far away, even at this late point in his life, and he was earning rave reviews as the lead in 1983’s “Inner Voices” before falling ill. On Oct. 10, 1983, he suffered a stroke and died. Both “Greystoke” and “Broad Street” were released after his passing, and Richardson earned a posthumous Oscar nomination for the former film.

The above TCM profile can also be accessed online here.