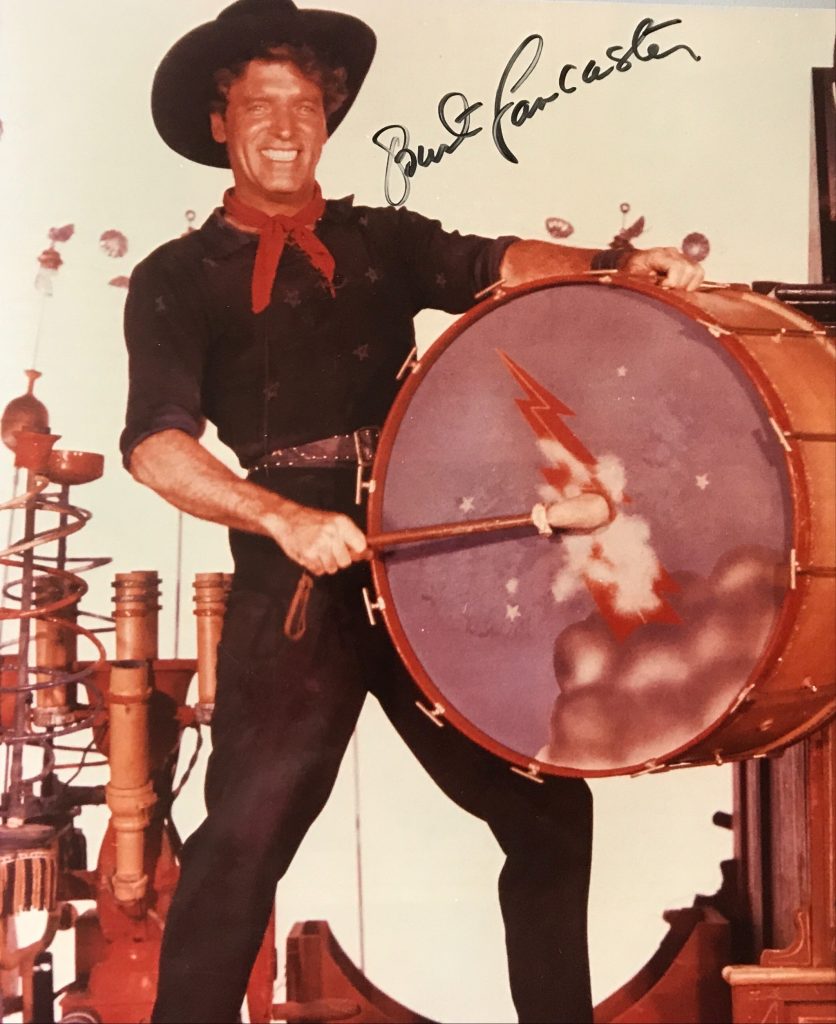

Burt Lancaster was an intriguing actor who gave many tremendous performances although he sometimes, to my mind, marred some movies with his overuse of his grin. He was born in New York in 1913. He began his show business career as a circus acrobat and used his athletic prowess in many of his movies. He had a starring role opposite Ava Gardner in his first movie “The Killers” in 1947. He has had many cinema highlights including “The Flame and the Arrow”, “The Professionals”, “The Leopard”, “Airport” and “Atlantic City”. He died in 1994 at the age of 80.

TCM overview:

Fame came to Burt Lancaster with his first film role, as the doomed Swede in Universal’s “The Killers” (1946), but the former circus acrobat knew better than to leave his career in other hands. After less than two years in Hollywood, Lancaster formed his own production company and took the lead in such popular successes as the Technicolor swashbucklers “The Flame and the Arrow” (1950) and “The Crimson Pirate” (1952) and the noble failure “Sweet Smell of Success” (1959), later called one the greatest films of all time. The athletic, savvy but passionate Lancaster remained a box office draw for 20 years, winning a 1961 Academy Award for playing the corrupt evangelist “Elmer Gantry” (1960), but his power to pull in moviegoers waned with the death of the studio system and his own disinterest in acting the Hollywood hero. Lancaster took chances in such challenging films as “The Swimmer” (1968), “Castle Keep” (1969) and “Ulzana’s Raid” (1972) while his best work through the next decade was often in European features like “1900” (1976) and “Atlantic City” (1980), which netted him an Oscar nomination. In his later years, the actor was better known to younger Americans from TV spots for MCI, the ACLU, and AIDS research, and for his final film role in the hit “Field of Dreams” (1989). Five years after his death in 1994, the American Film Institute pointed a new generation of film fans Burt Lancaster’s way when they conferred upon him the posthumous designation of living legend. Burton Stephen Lancaster was born on November 2, 1913, in the largely immigrant community of East Harlem in New York City. Lancaster’s father, a second generation Irish-American and postal clerk at Manhattan’s General Post Office, had won song and dance competitions in his youth based on the strength of his rich tenor voice and his mastery of several musical instruments. His mother, the former Elizabeth “Lizzie” Roberts, had had three children before him and one after his birth, who died in infancy. Lancaster’s given name was in tribute to the surgeon who delivered him. Growing up in an Irish-Protestant household, he learned the ideals of honesty and charity but developed a yearning for adventure while exploring the streets of Manhattan. Early work came with a paper route and a job shining shoes outside of Macy’s Department Store. A preteen Lancaster was knocked down by automobiles no less than eight times and once broke his nose falling from a fire escape. During the Depression, he performed in plays at the Union Settlement House in East Harlem and worked as a basketball coach. An incident in which Lancaster was stabbed accidentally by a friend led to a near fatal staph infection and a year’s confinement in bed. A star basketball player at DeWitt Clinton High School, Lancaster continued to New York University on an athletic scholarship. He quit NYU in 1932 to join the one-ring Kay Brothers Circus. After a single season, Lancaster moved to the Russell Brothers Circus and, later, with his marriage to acrobat June Ernst, to the three-ring Barnett Brothers Circus. Lancaster finished out the 1935 summer season working at Luna Park in Coney Island before going on government relief. Applying for a job with the Works Progress Administration, he performed in WPA-sponsored circuses. After an injury to his hand and the dissolution of his first marriage, Lancaster worked as a lingerie salesman in Chicago and singing waiter in New Jersey before joining the U.S. Army’s Twenty-First Special Service Division during World War II. As part of the Army Service Forces, Lancaster put on shows for shell-shocked soldiers fresh from the frontlines, relying on his talents as a gymnast and vaudevillian to entertain the troops and his facility as a scrounger to retrieve props and costumes from bombed out buildings in Rome. Back in the United States post-war, Lancaster pursued an acting career with some diffidence. He made his Broadway debut as Burton Lancaster in Harry Brown’s wartime drama “A Sound of Hunting,” the source for Edward Dmytryk’s 1952 film “Eight Iron Men.” Though the production closed after 12 performances, Lancaster caught the eye of Hollywood agent Harold Hecht. Hecht provided Lancaster with an introduction to producer Hal Wallis, who paved the way for the actor’s debut as the doomed Swede in Robert Siodmak’s noir classic “The Killers” (1946) at Universal. Siodmak and cinematographer Elwood Bredell employed stark chiaroscuro lighting to offset Lancaster’s angular face and chiseled physique, creating an instant Hollywood star, along with his co-star Ava Gardner. Reviews of the day referred to Lancaster as a “brawny Apollo” and a “brute with the eyes of an angel.” He celebrated his success by inhabiting plush new digs in Malibu’s Pacific Palisades, into which he would move his family and his second wife, Norma Anderson, with whom he had already conceived one child. Lancaster’s film roles through the next few years traded on his tough guy image in such films as Jules Dassin’s “Brute Force” (1947), Byron Haskin’s “I Walk Alone” (1948) and Robert Siodmak’s “Criss Cross” (1949). He varied the image slightly, playing Barbara Stanwyck’s weakling husband in Anatole Litvak’s “Sorry, Wrong Number” (1948) and Edward G. Robinson’s conscience-bound son in Irving Reis’ “All My Sons” (1948), a personal project for which he took a $50,000 salary cut. With agent Hecht, Lancaster formed his own production company. Hecht-Lancaster enjoyed its first popular success with the swashbuckler “The Flame and the Arrow” (1950), directed by Jacques Tourneur. This and subsequent films, such as Michael Curtiz’ “Jim Thorpe: All American” (1951) and Robert Siodmak’s “The Crimson Pirate” (1952), allowed the actor to showcase his natural athleticism, while straight dramas such as Daniel Mann’s “Come Back, Little Sheba” (1952) and Fred Zinnemann’s “From Here to Eternity” (1953), for which he was nominated for an Academy Award, encouraged him to stretch and mature as a performer. Pushing into middle age, Lancaster enjoyed a string of star turns in such high-profile productions as Robert Aldrich’s “Vera Cruz” (1954) opposite Gary Cooper, Daniel Mann’s “The Rose Tattoo” (1955) with Italian actress Anna Magnani, and as the title character in Joseph Anthony’s “The Rainmaker” (1956), co-starring Katharine Hepburn. Lancaster tried his hand at directing a feature with “The Kentuckian” (1955) and financed with Hecht and producer James Hill the Academy Award-winning “Marty” (1955), starring Ernest Borgnine. A pet project was the Hecht-Hill-Lancaster production “Sweet Smell of Success” (1957), a scalding expose of the New York publicity industry with Lancaster playing a thinly-veiled caricature of gossip columnist Walter Winchell. Shot on location in Manhattan by James Wong Howe and briskly directed by Alexander Mackendrick, the film was a box office disappointment whose failure wounded Lancaster deeply. More successful that year was John Sturges’ “The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral” (1959), in which Lancaster played frontier lawman Wyatt Earp to Kirk Douglas’ hair-trigger Doc Holliday. Lancaster won an Academy Award for his portrayal of corrupt evangelist “Elmer Gantry” (1960) but the milestone also marked the downward arc of his tenure as a Hollywood leading man. Nonetheless, the actor received another Oscar nod for playing Robert Franklin Stroud, a criminal recidivist known as the “Birdman of Alcatraz” (1962), and traveled to Italy to work for Luchino Visconti in “The Leopard” (1963), opposite Alain Delon and Claudia Cardinale. A crowd pleaser for Lancaster was “The Professionals” (1966), a rousing Western co-starring Lee Marvin, Woody Strode and Robert Ryan. More pet projects included John Frankenheimer’s “The Train” (1964), Frank Perry’s “The Swimmer” (1968), and Sydney Pollack’s “Castle Keep” (1969). Uninterested in playing heroes or characters with whom he was in agreement politically, Lancaster seemed to relish thwarting audience expectations. Going through the motions in Arthur Hiller’s cash cow “Airport” (1970), Lancaster was more in his element in a string of revisionist Westerns, among them Robert Aldrich’s grim Vietnam parable “Ulzana’s Raid” (1972). He directed a second film, the murder mystery “The Midnight Man” (1974), and traveled to the Middle East to appear as “Moses, the Lawgiver” (1976), with his own son Bill contributing a cameo as the young Moses. Better late-life roles for Lancaster were as Robert De Niro’s autocratic grandfather in Bernardo Bertolucci’s “1900” (1976) and as a military advisor in the Vietnam War drama “Go Tell the Spartans” (1979), directed by Ted Post. Now firmly in elder statesman mode, the actor scored sterling notices for his roles as an aging gangland flunky in Louis Malle’s “Atlantic City” (1980) – which earned him his fourth and final Academy Award nomination – as an elderly outlaw in Lamont Johnson’s distaff Western “Cattle Annie and Little Britches” (1981), and as an astronomy-obsessed Texas oilman in Bill Forsythe’s wry comedy “Local Hero” (1983). Near the end of his life, Lancaster capped his career by reteaming with frequent co-star Kirk Douglas for Brian De Palma’s “Tough Guys” (1986), playing the dying patriarch of a sprawling but dysfunctional Long Island family in Daniel Petrie’s “Rocket Gibraltar” (1988) and appearing in the small but memorable role of an aging baseball rookie who remembers his glory days with the Chicago White Sox in the Kevin Costner classic “Field of Dreams” (1989). The production marked Lancaster’s last feature film appearance and one of his most successful. In his final years, Lancaster was a tireless spokesman for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the People for the American Way, liberal political organizations either targeted for derision by then-President George H. W. Bush as un-American or founded to counter the demographic swing in the United States toward conservatism. Lancaster also appeared in print ads supporting aid for AIDS and TV spots that urged consumers to be wary of the bold claims of the large pharmaceutical companies. Though he projected the image of ageless vitality well into his seventies, Lancaster was plagued by heart troubles, requiring quadruple bypass. In 1990, he suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. Burt Lancaster died of a heart attack on Oct. 21, 1994, at his home in Century City, CA, just weeks before his 81st birthday. In 1999, the American Film Institute ranked the actor at 19th on its list of “50 Male Movie Legends.” By Richard Harland Smith

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.