Guardian obituary:

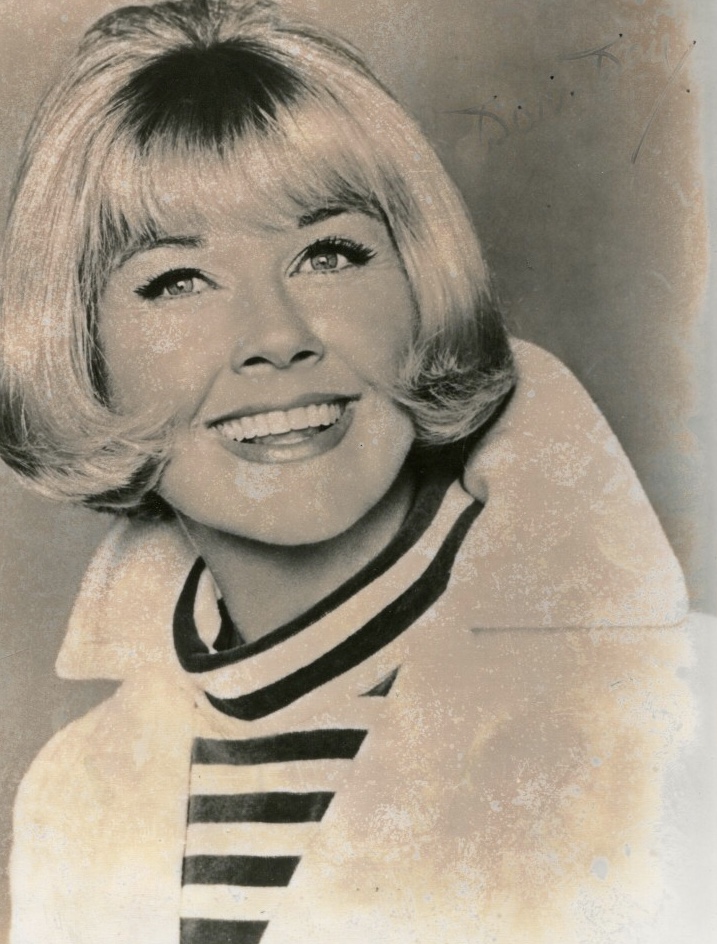

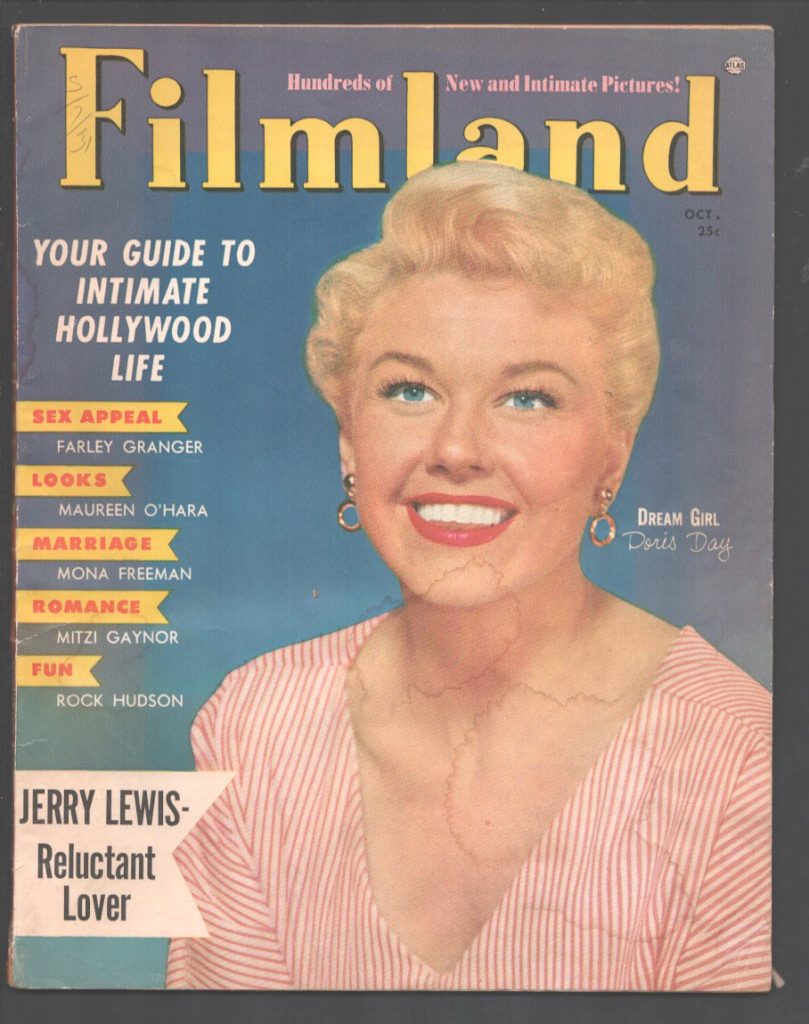

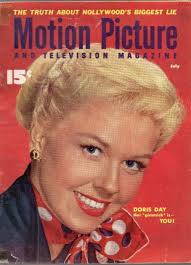

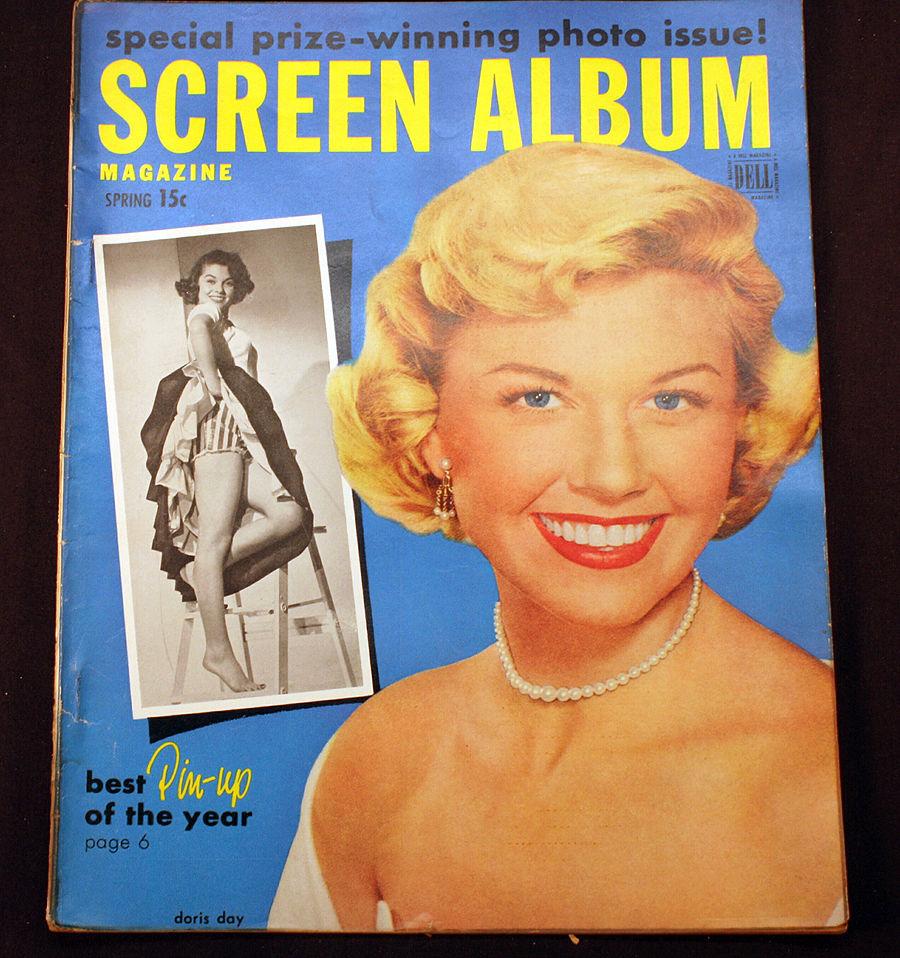

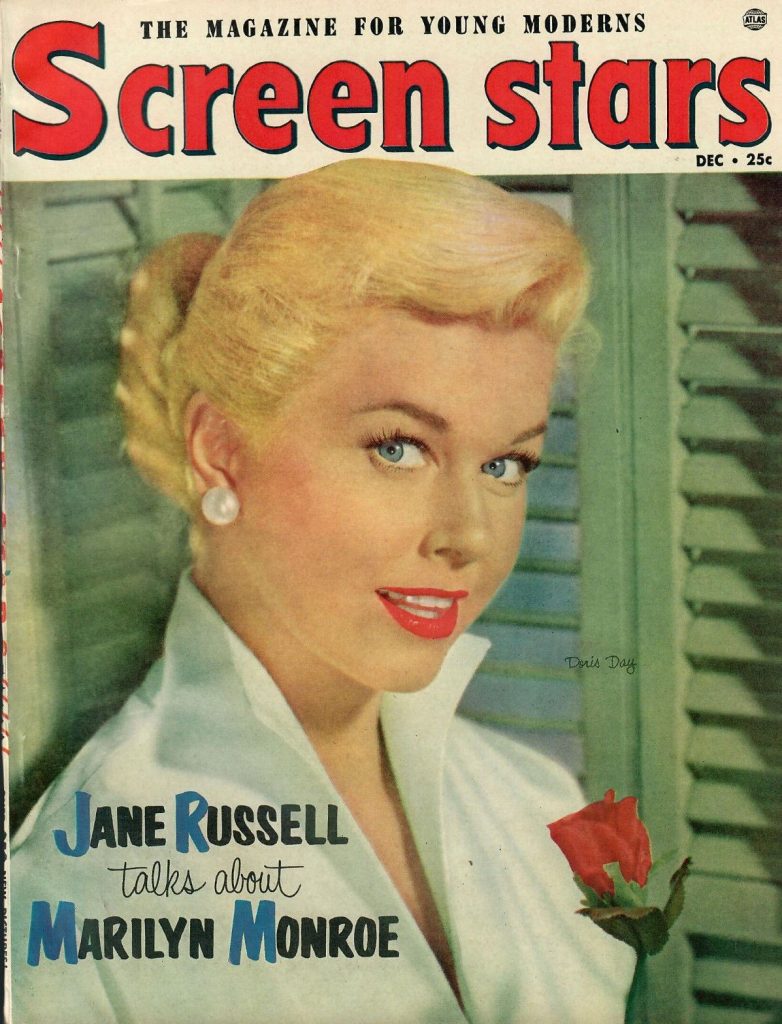

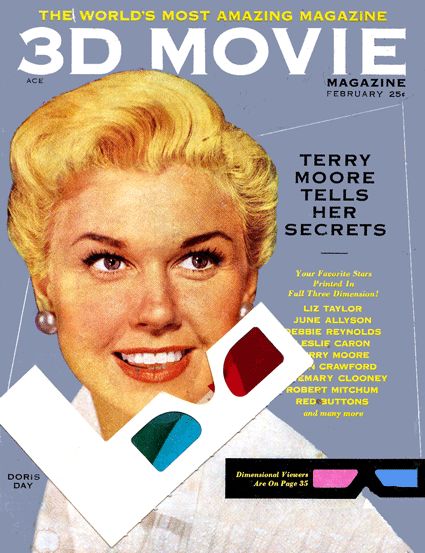

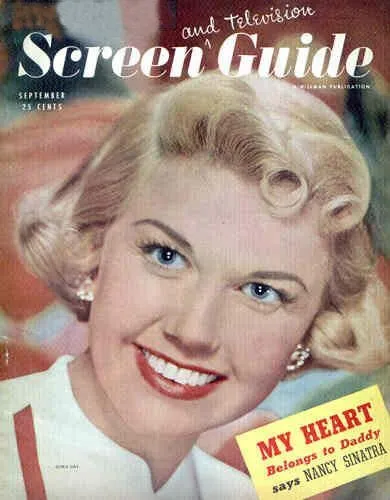

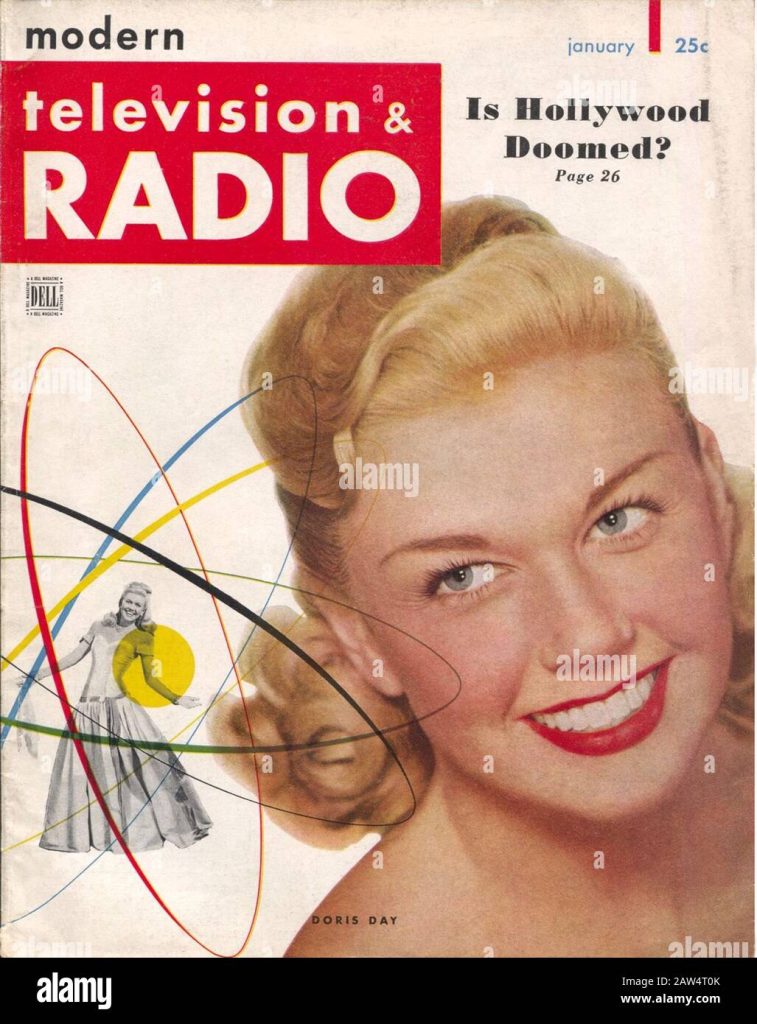

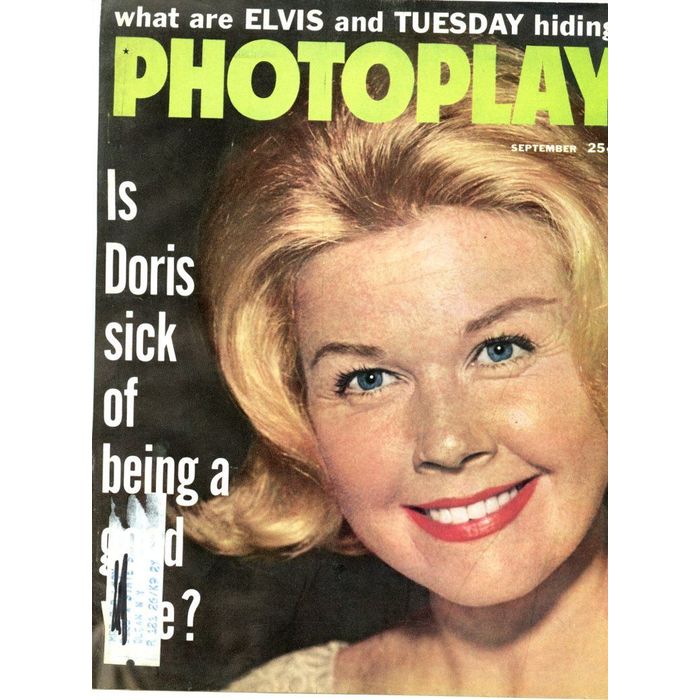

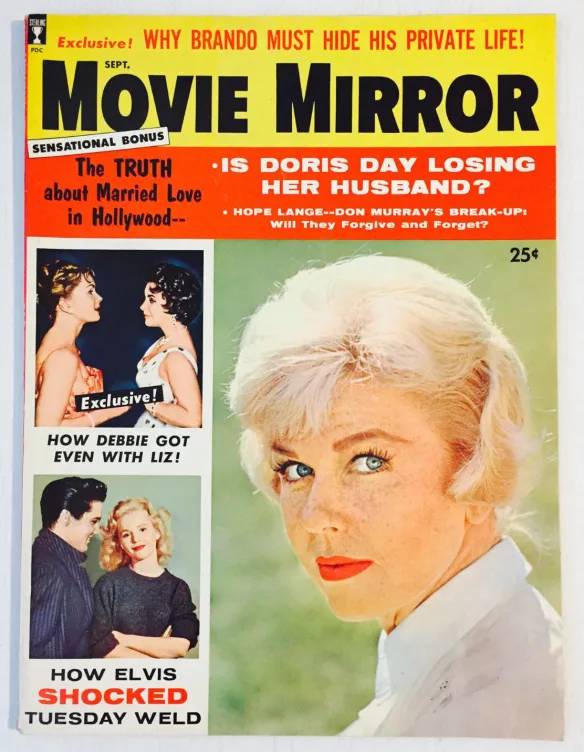

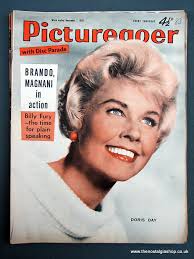

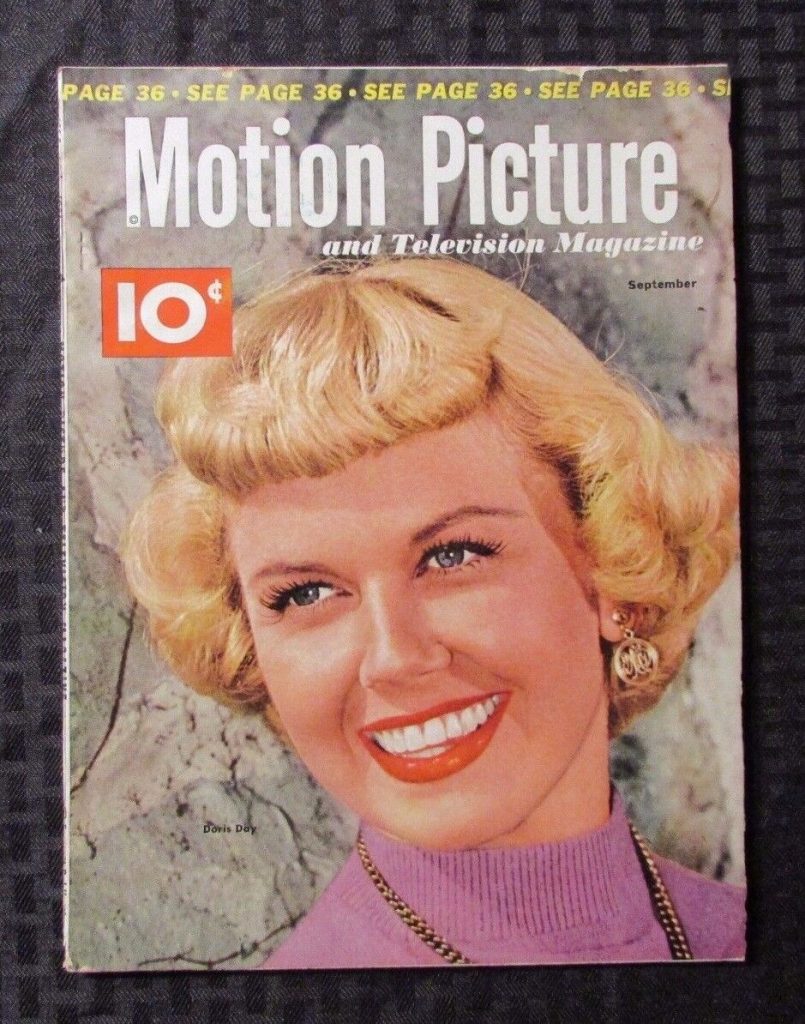

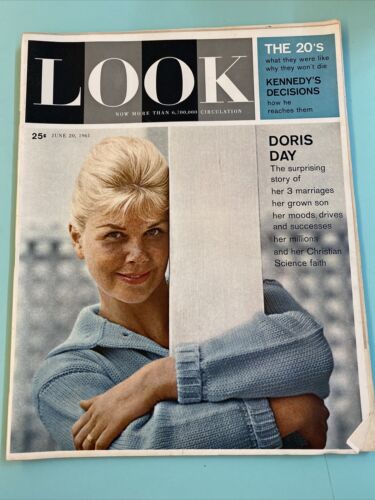

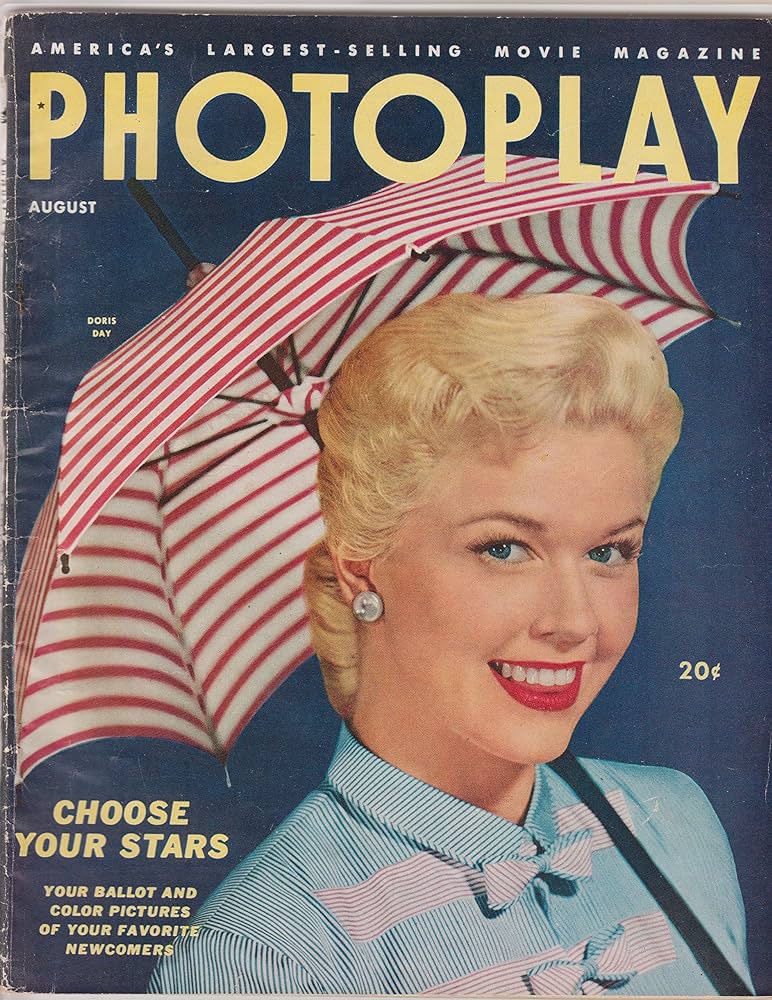

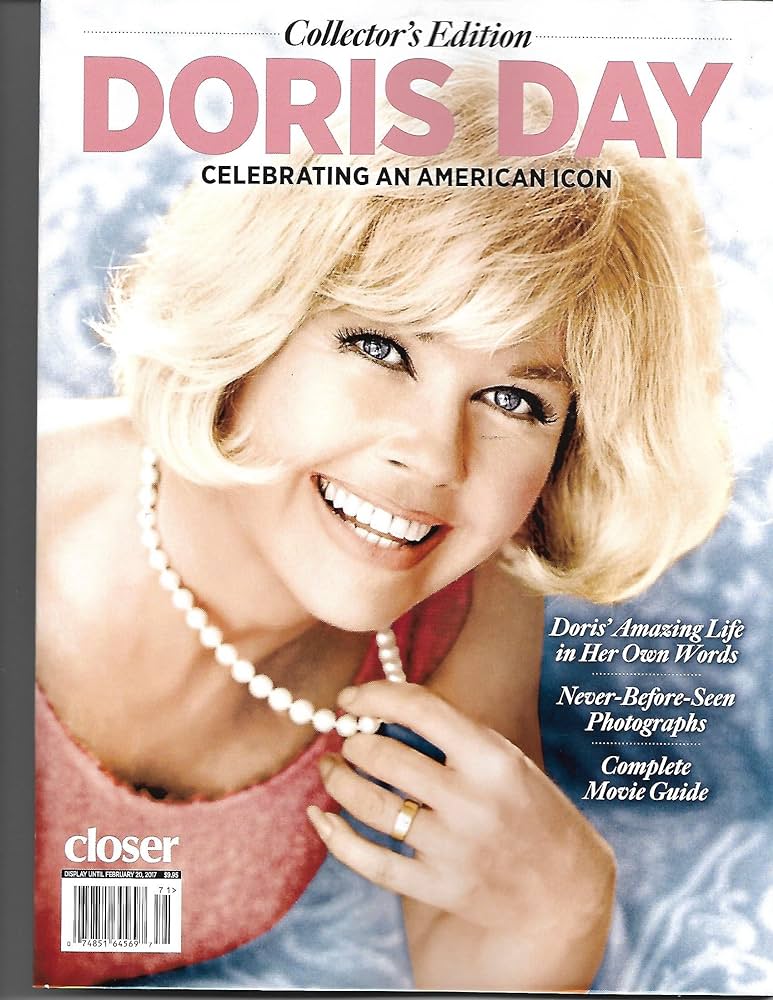

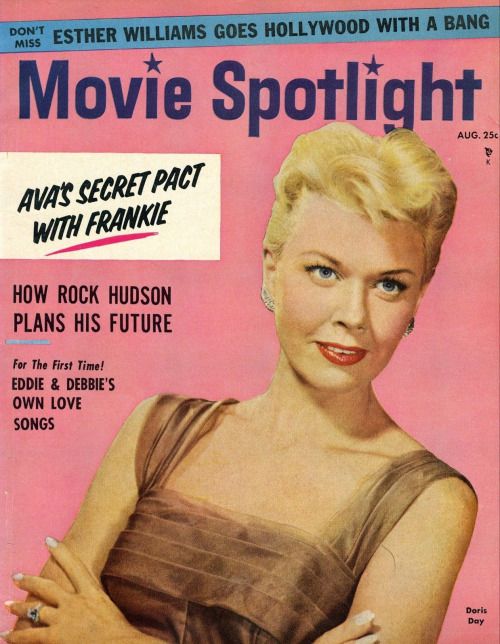

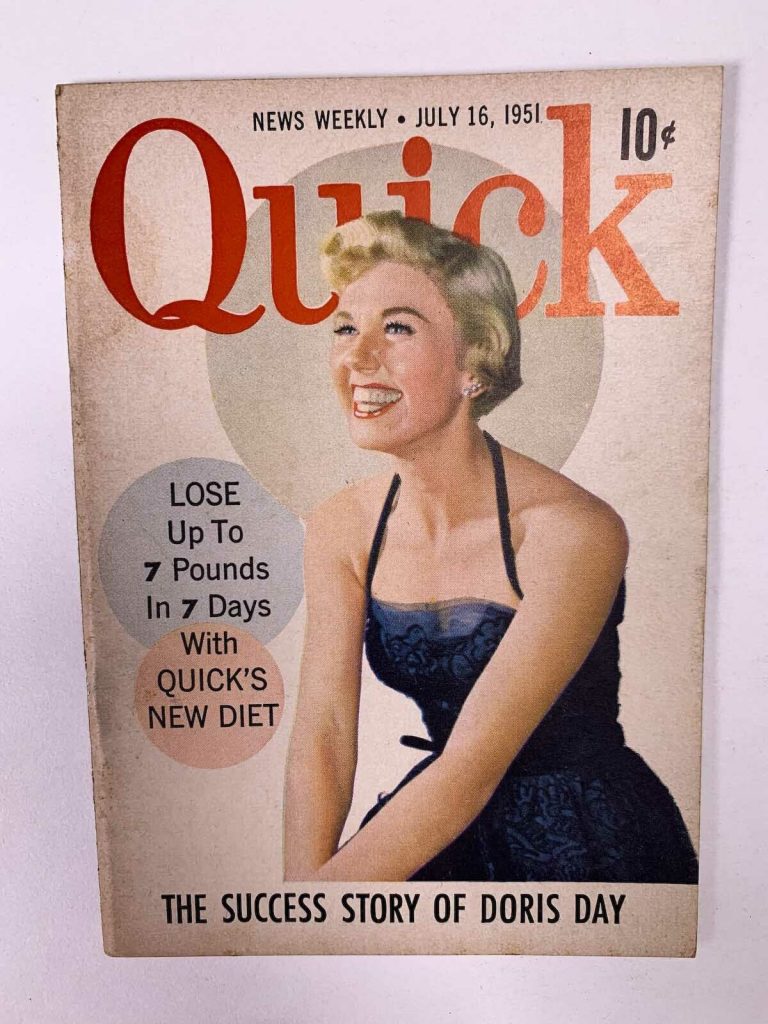

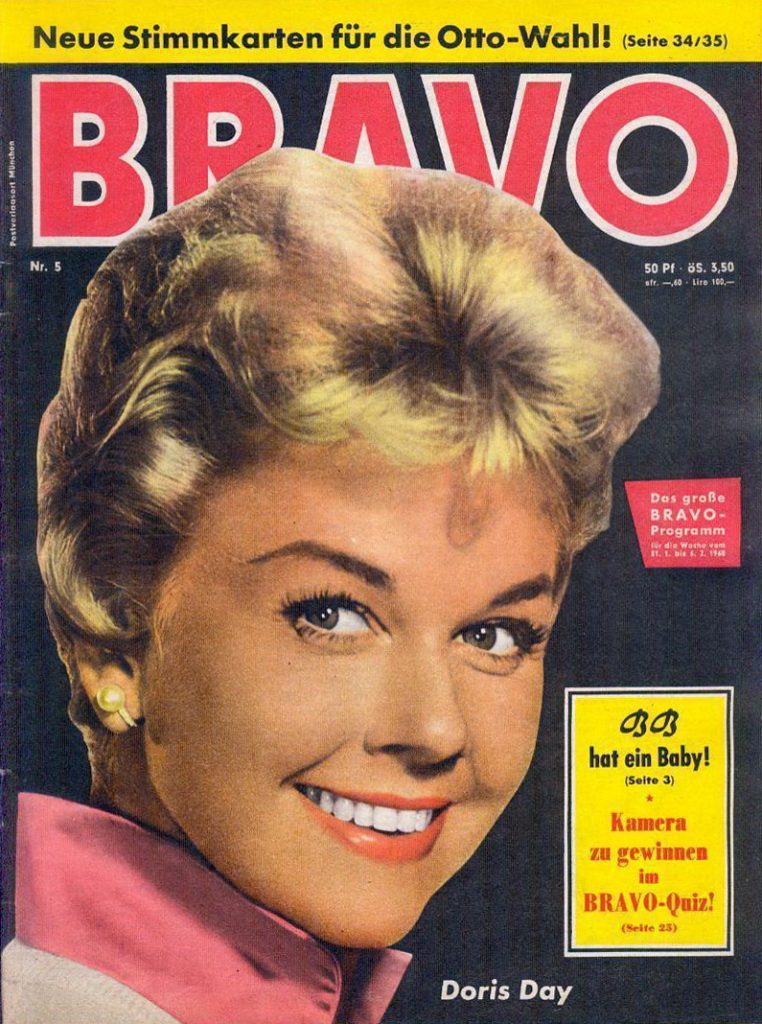

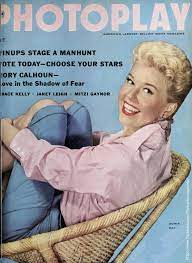

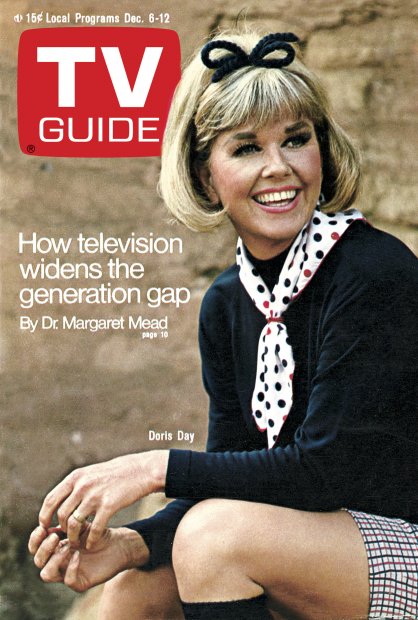

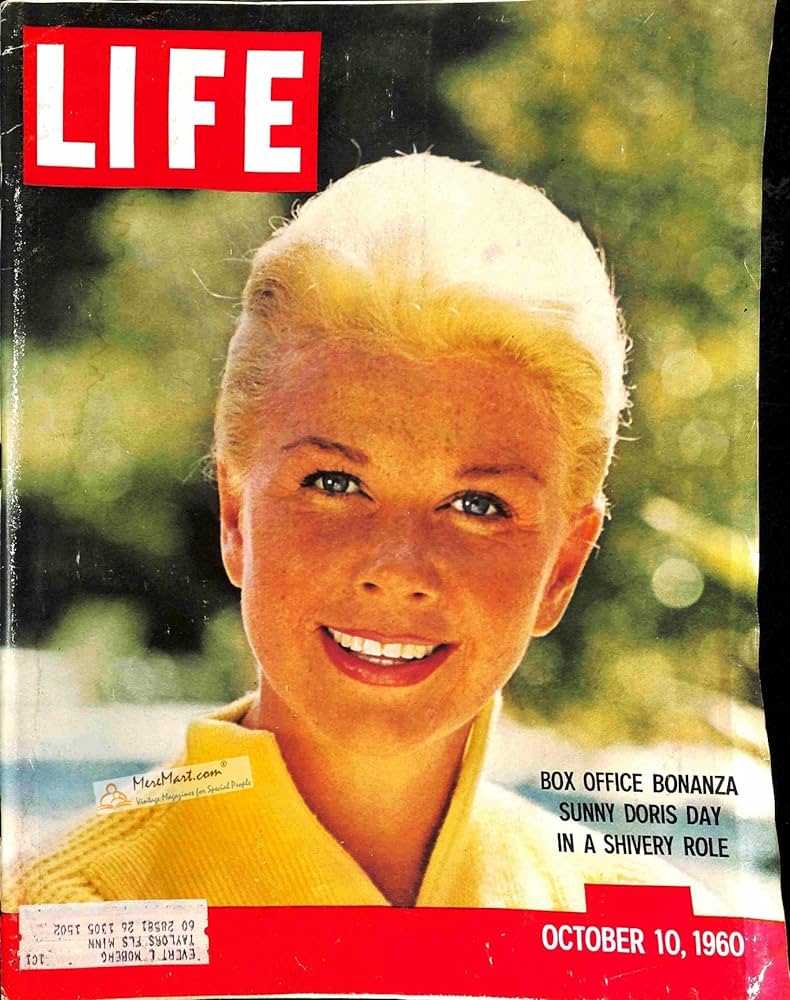

Doris Day, who has died aged 97, was a singer who came out of the big-band boom of the 1940s to become one of Hollywood’s top box-office stars throughout the 50s and 60s. She had a honey voice, short, buttercup-coloured hair, a sunny smile – and as many scruples as freckles. If Marilyn Monroe was the “girl downtown” at 20th Century Fox, Day was the archetypal “girl next door” at Warners.

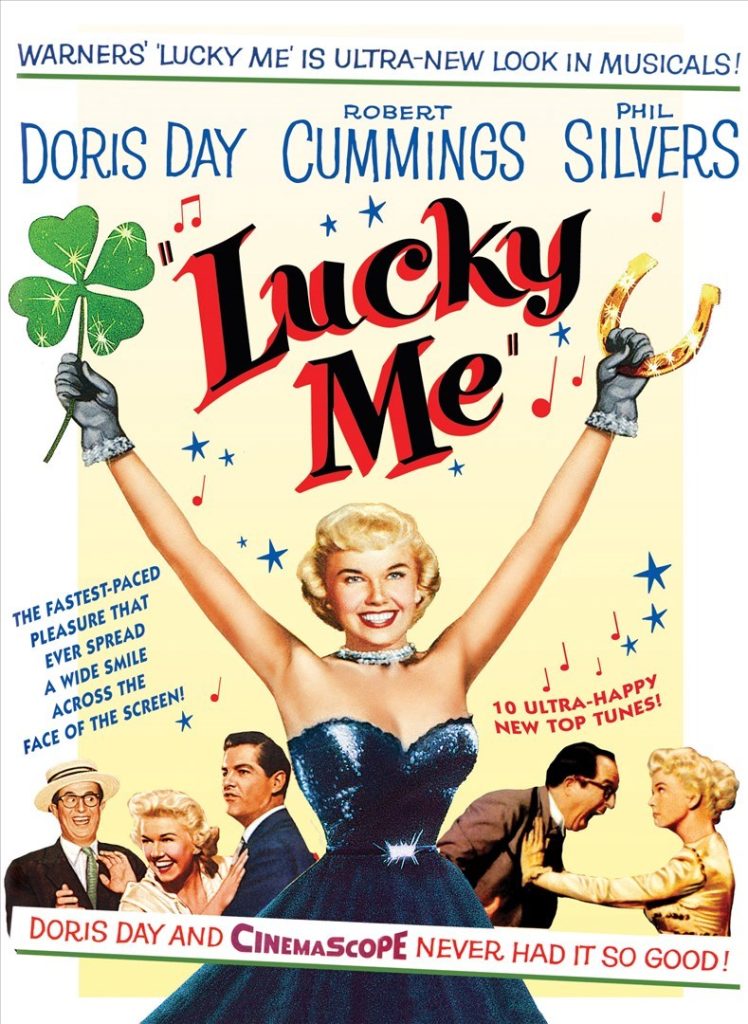

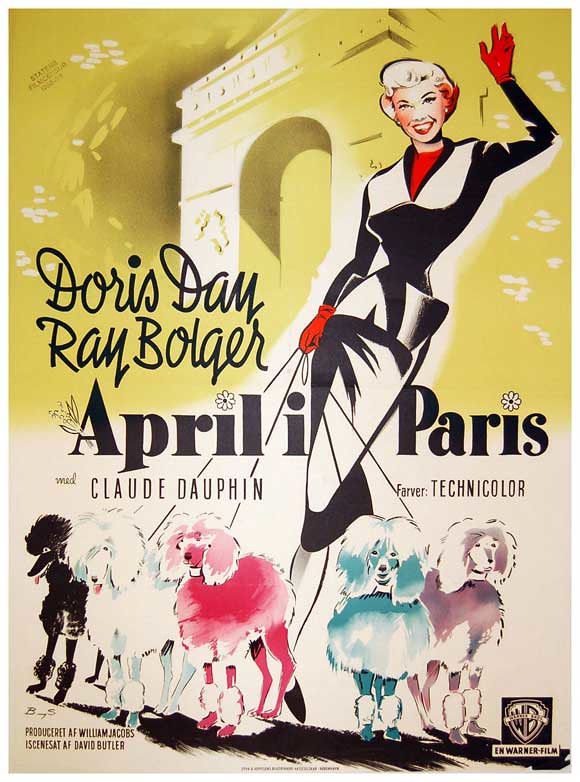

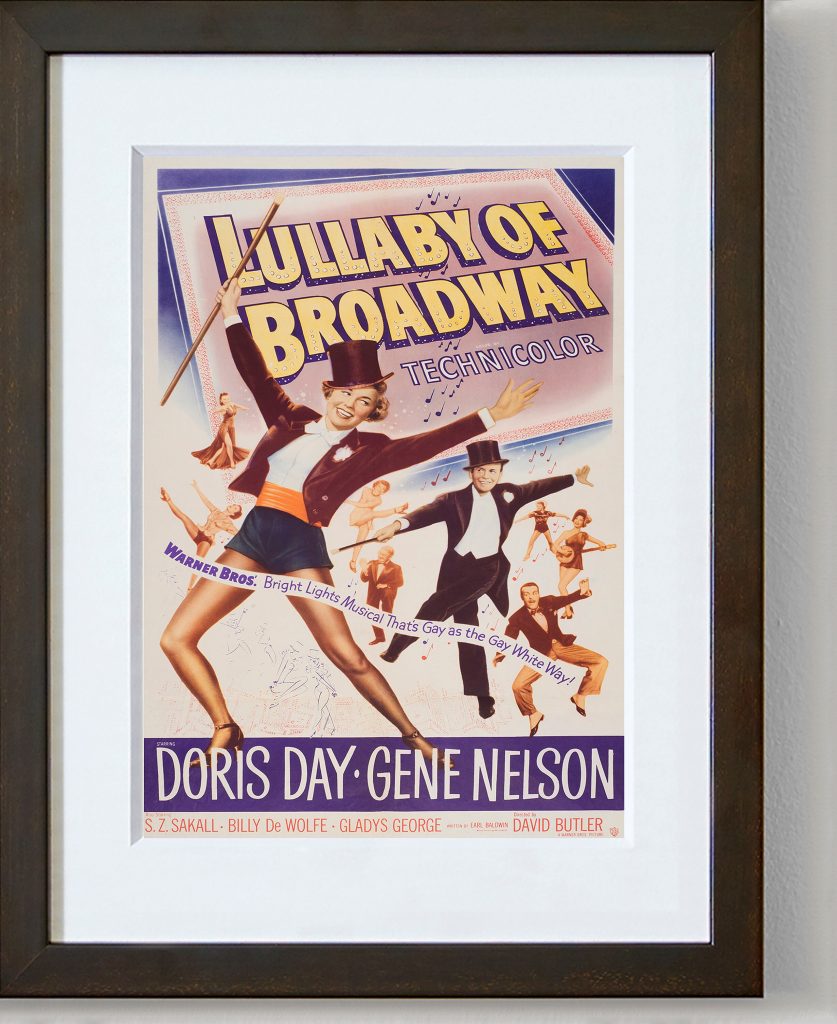

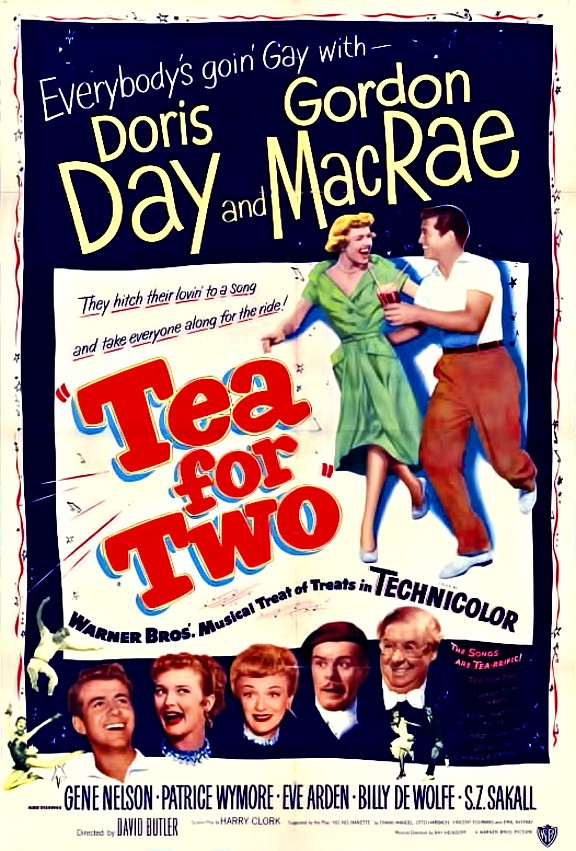

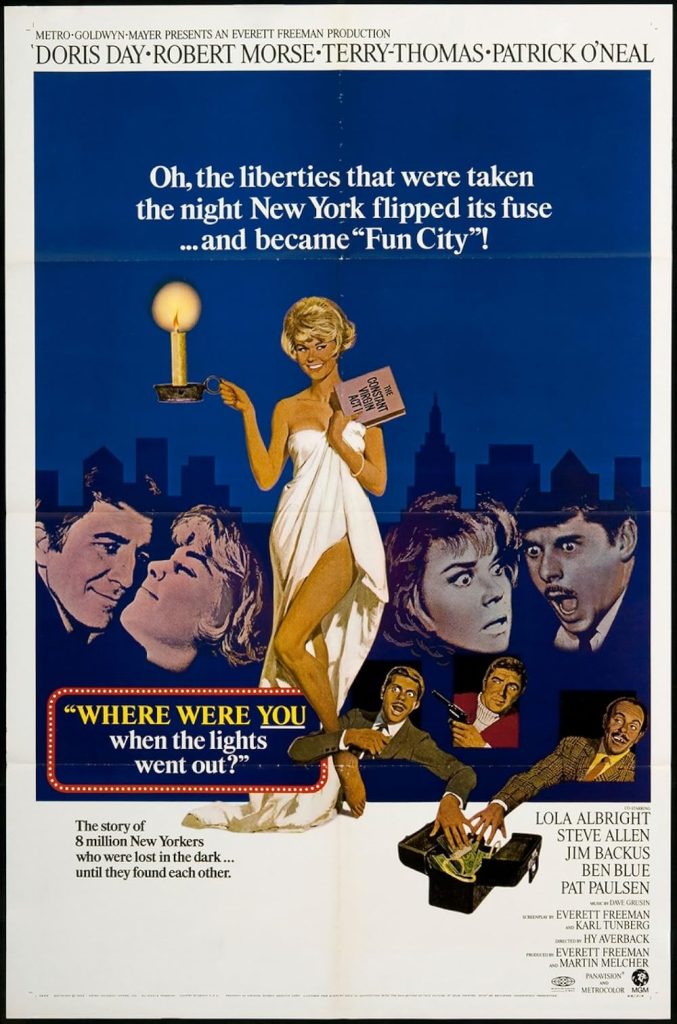

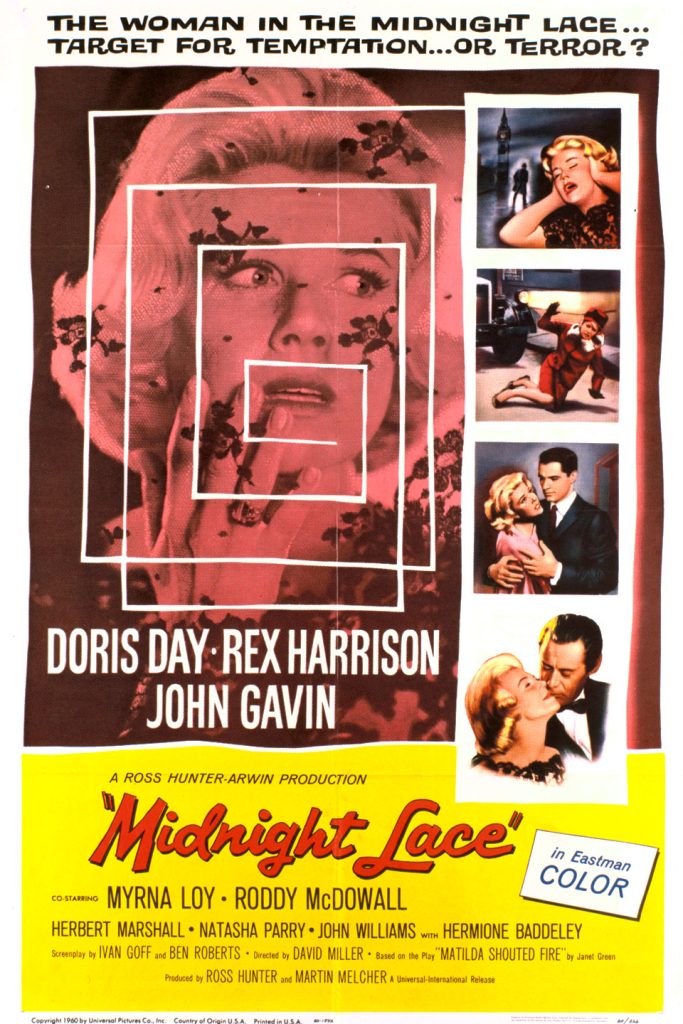

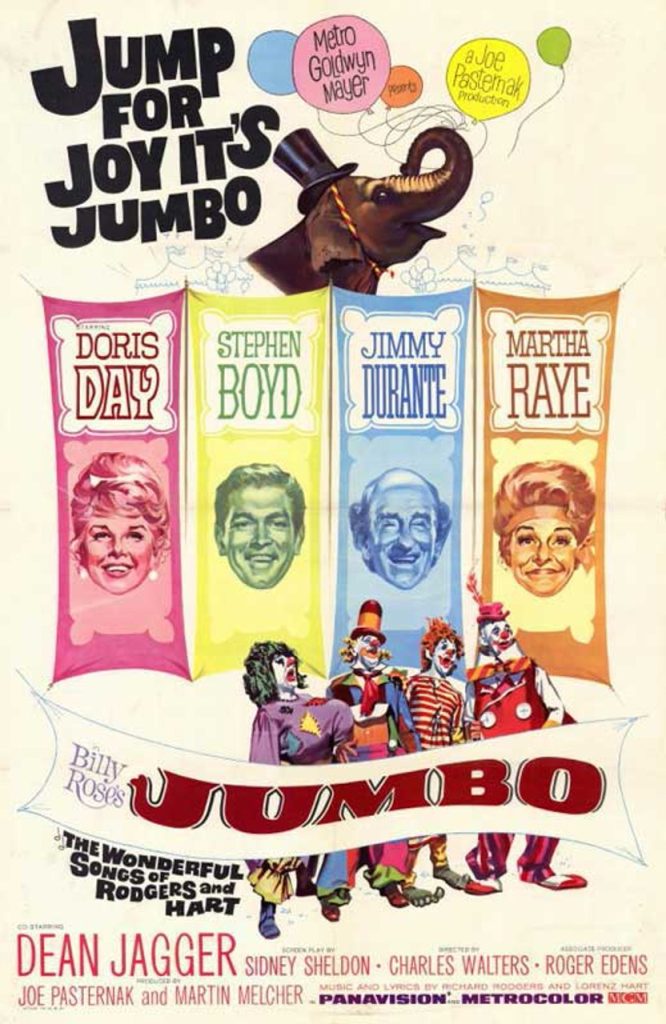

Day was first seen as a spunky but naive showgirl in more than a dozen candyfloss Warner Bros musicals between 1948 and 1955. Then, from 1959 until her retirement from the big screen in 1968, she became a sophisticated urban woman defending her honour and independence in a series of glossy, sex-battle romantic comedies for Universal Studios.

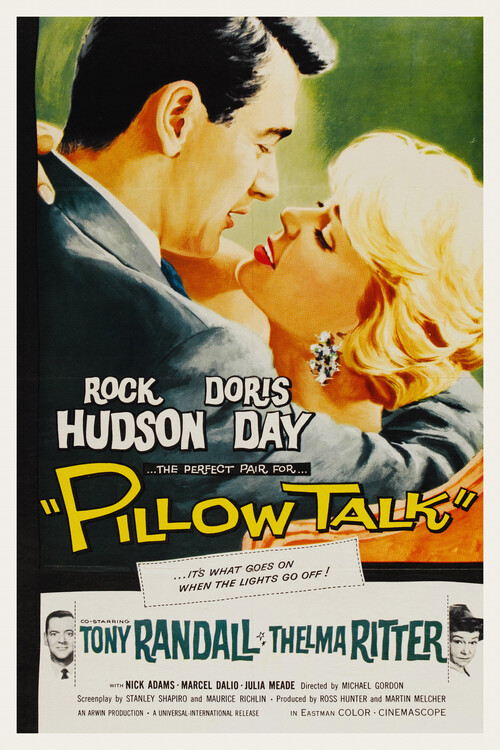

During this crowning period of her film career, she showed a real flair for comedy. Wearing dotty hats and stylish Jean Louis gowns, she played a series of women determined not to sacrifice their independence for the sake of a man or, at least, without a fight. This was best displayed in the three entertaining romantic comedies she made opposite Rock Hudson: Pillow Talk (1959), which earned her an Oscar nomination as best actress), Lover Come Back (1961) and Send Me No Flowers (1964), in which the pair were rivals-cum-lovers, she a decent working girl, he an amorous rogue. At one stage in Lover Come Back, someone compares Hudson to a bad cold. Day replies: “There are two ways to handle a cold. You can fight it or you can give in and go to bed with it.”

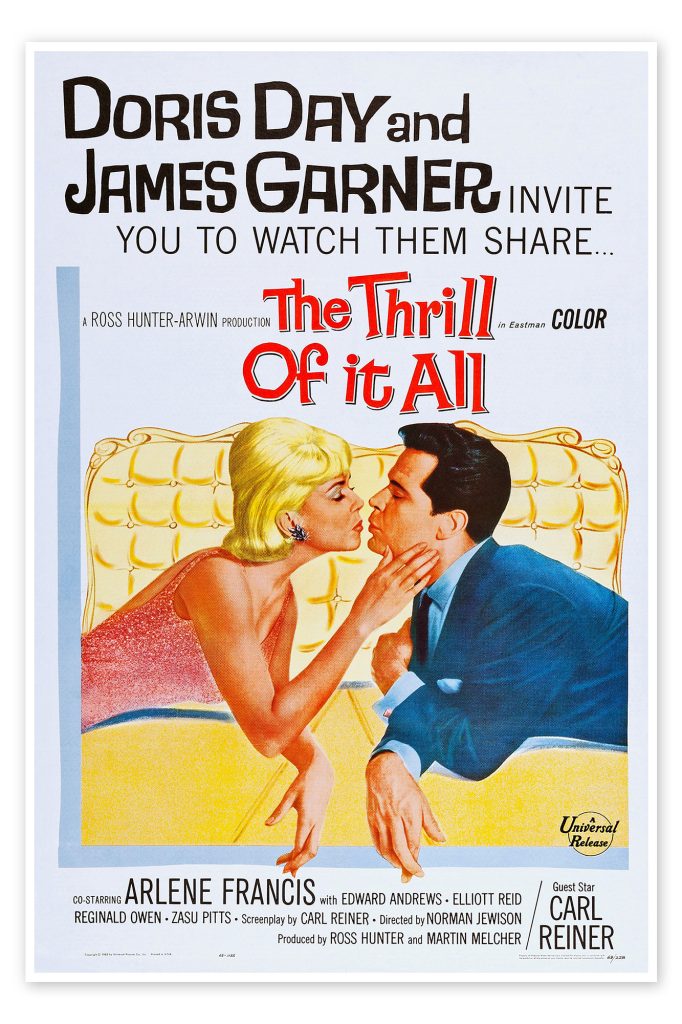

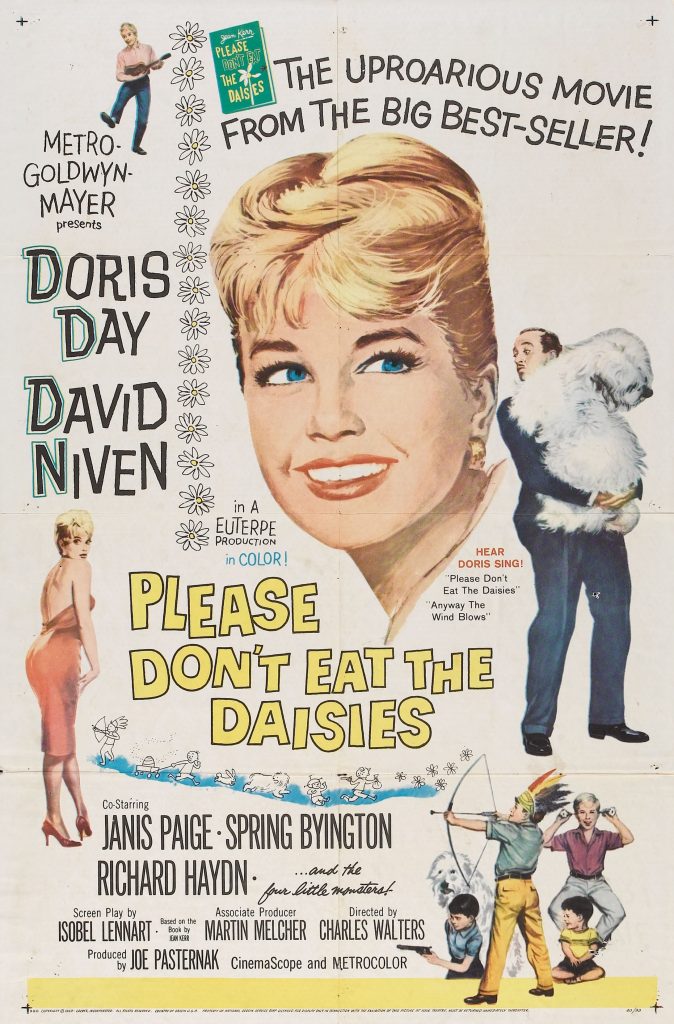

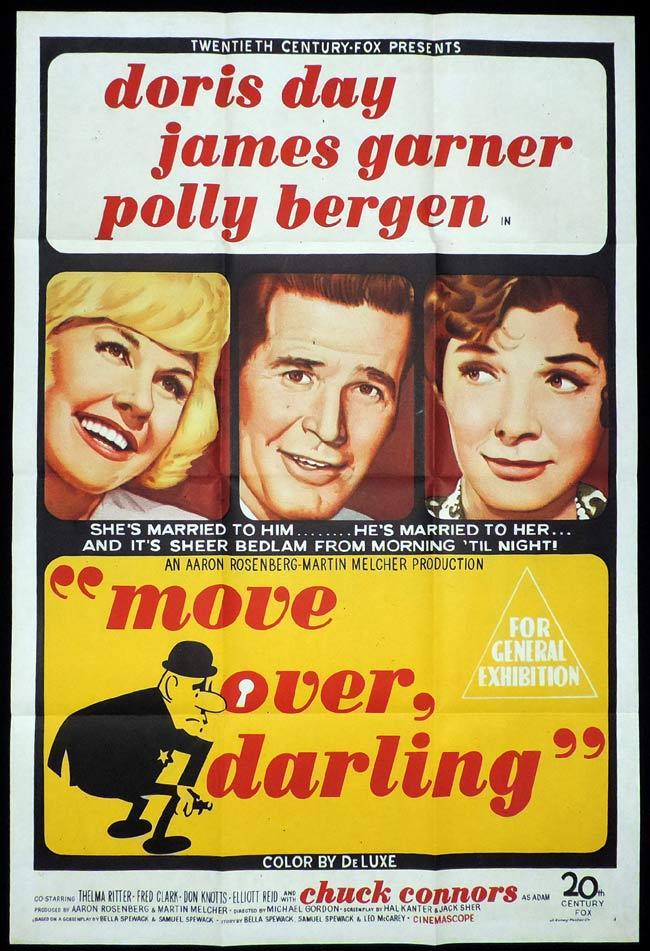

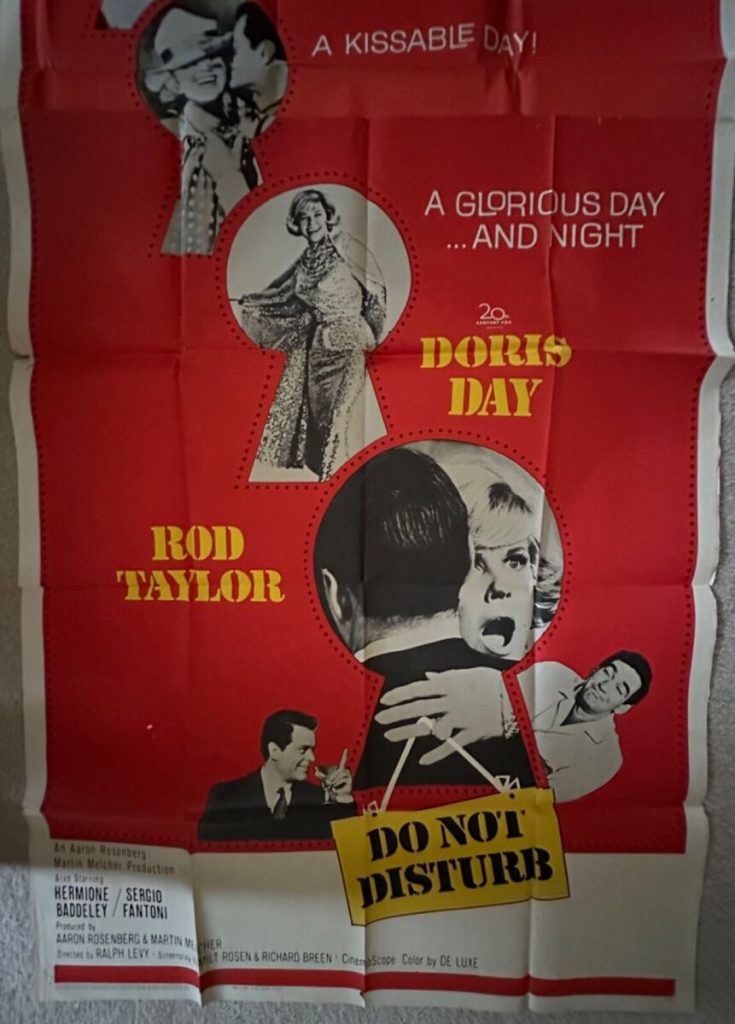

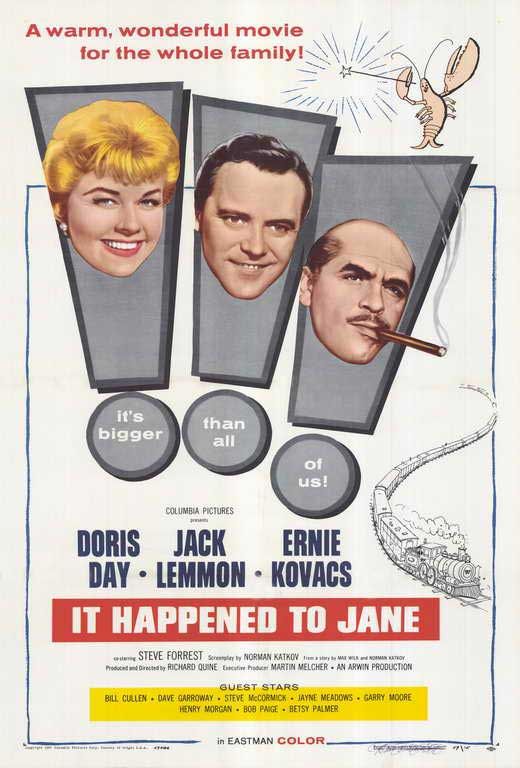

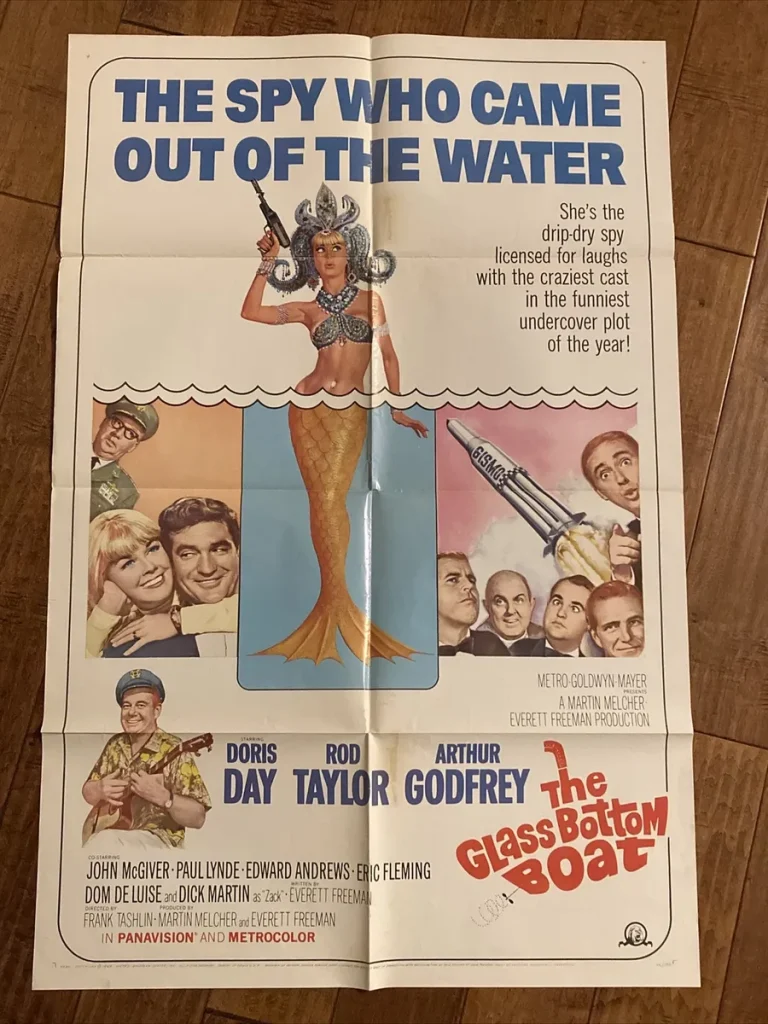

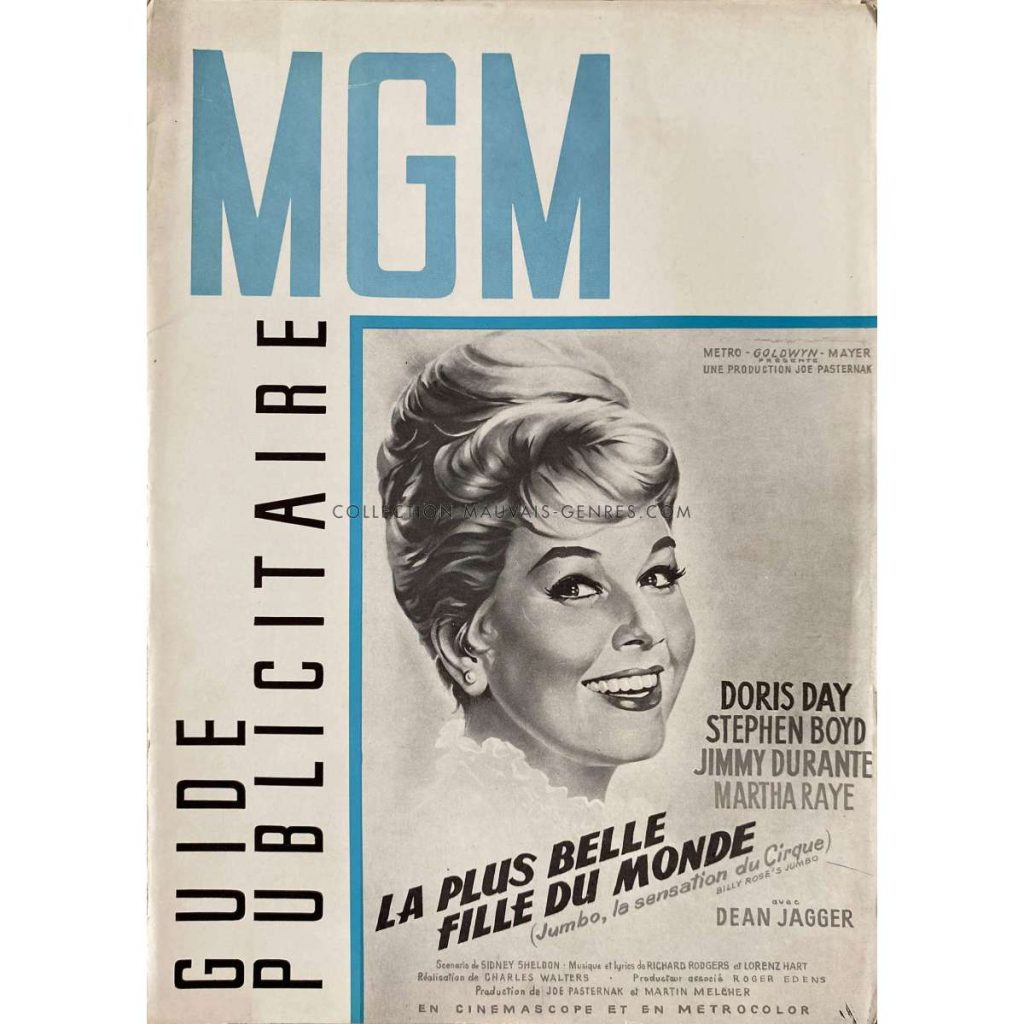

Day played variations of the same character in That Touch of Mink (1962), with Cary Grant; Move Over, Darling and The Thrill of It All (both 1963), with James Garner; and Do Not Disturb (1965) and The Glass Bottom Boat (1966), with Rod Taylor, but none of these later leading men provided the chemistry she had had with Hudson.

Of her film persona in the 60s, the critics Jane Clarke and Diana Simmonds wrote that Day “confronts the male and forces him to modify his attitudes and behaviour. Moreover, saying no to manipulative sexual situations is not the same as clinging to one’s virginity.”

Day might have lived a charmed existence in many of her movies, but her life was not all sunshine and roses. She was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, of German ancestry and when she was eight years old, her parents – William Kappelhoff, a music teacher, and Alma (nee Welz) – split up. When Doris was 15, her promising career as a dancer was halted by a car accident. She had a lengthy recovery, during which her mother encouraged her to start singing after hearing her daughter joining in with singers including Ella Fitzgerald on the radio. “There was a quality to Ella’s voice that fascinated me, and I’d sing along with her, trying to catch the subtle ways she shaded her voice, the casual yet clean way she sang the words,” Day recalled.

She began a career as a vocalist with Barney Rapp’s band in 1939. It was Rapp who got her to change her name to Doris Day after hearing her sing Day After Day. Initially, she thought the name sounded “phoney”, but she gradually accepted that Kappelhoff was a little too long for the marquee outside the theatre.

While on the road with the band in 1941, aged 19, she married the trombonist Al Jorden, with whom she had a son, Terry. Jorden turned out to be a jealous wife-beater. They divorced in 1943. At the same time, Day was making an impression with Les Brown and His Band of Renown. In 1945, she had a hit with their recording of Sentimental Journey, which coincided with the end of the second world war in Europe and became an unofficial homecoming theme for many veterans.

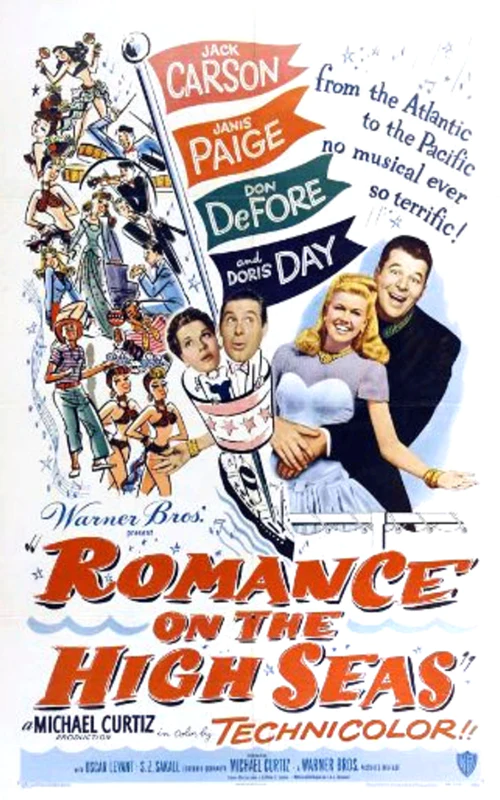

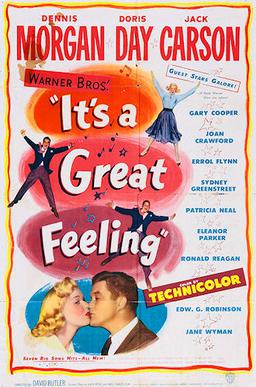

After a second unhappy marriage, to the saxophonist George Weidler, ended in divorce in 1949, luck was on her side when Betty Hutton got pregnant just before the shooting of Romance on the High Seas (1948) at Warners. Day was given top billing in her first feature by the film’s producer-director, Michael Curtiz, after she delivered an emotional version of George and Ira Gershwin’s Embraceable You at the audition. Impressed by her voice and wholesome good looks, Curtiz signed her to a film contract, although she had never acted before.

Day’s debut movie, which had her singing five songs, including the Oscar-nominated It’s Magic (the film’s title in the UK), was the first of a series of lightweight Warners musicals tailored for her, for which her singing was the raison d’être. Most of her numbers were performed in nightclubs or in stage shows; they seldom advanced the plot, although they sometimes reflected the state of mind of the innocent character she was playing.

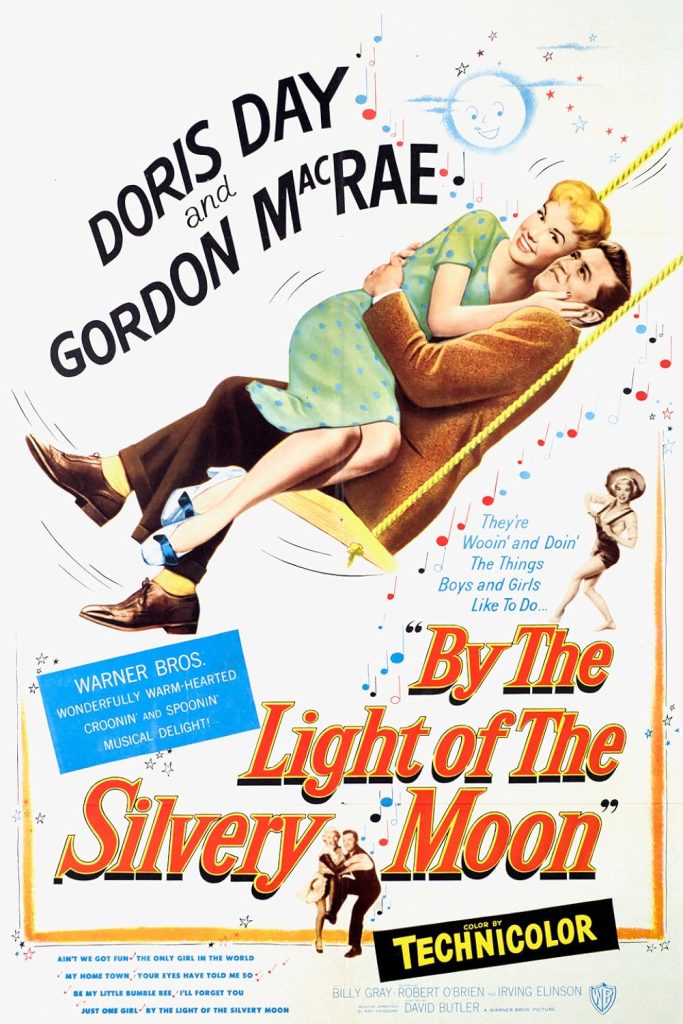

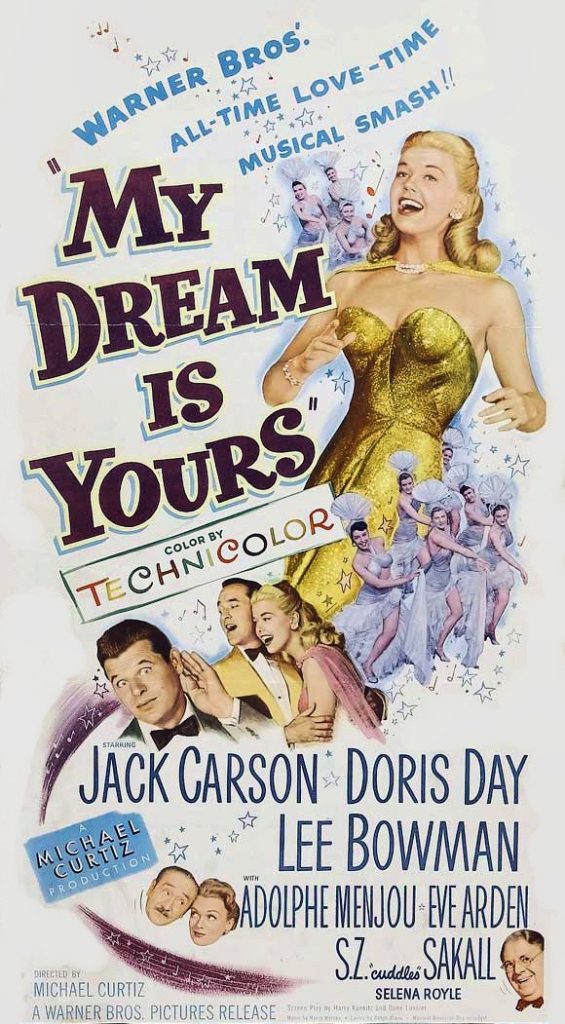

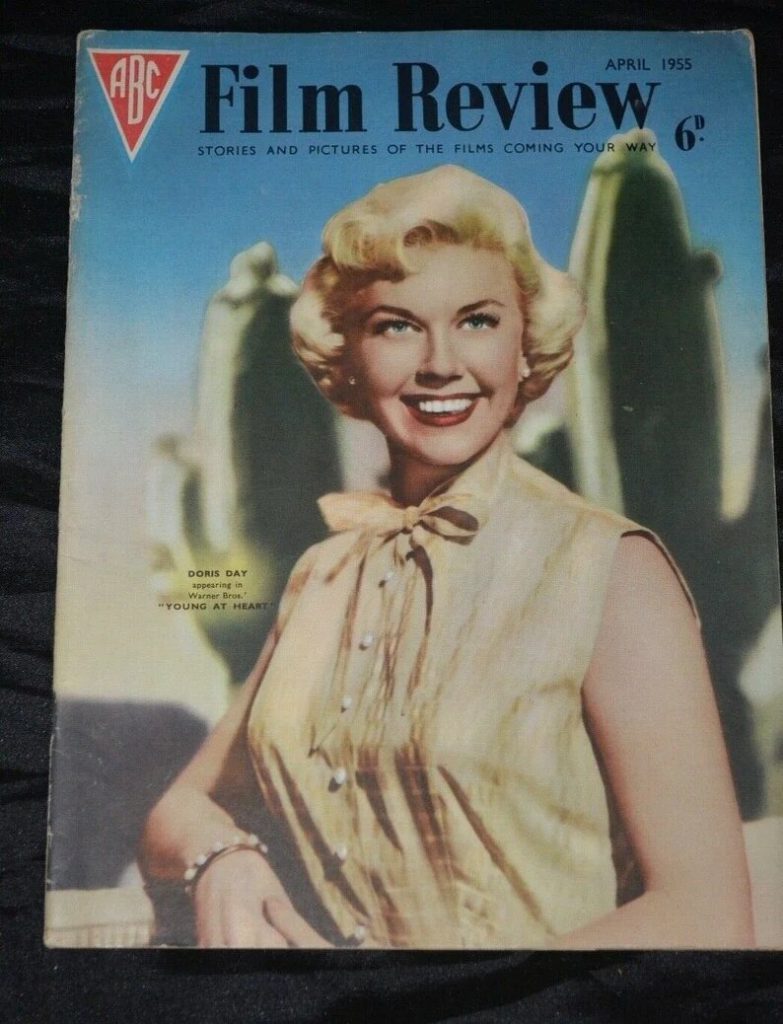

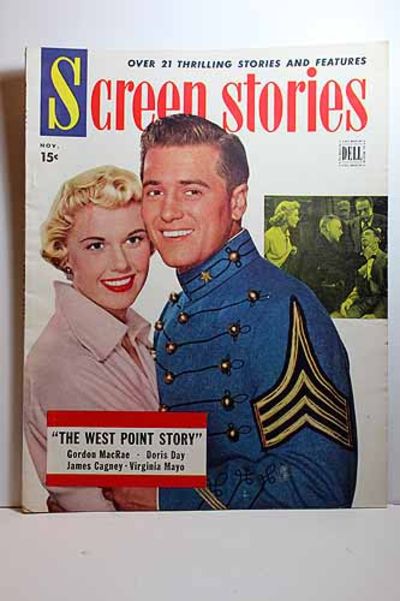

The freshness and vitality of her singing and personality blew the cobwebs off the plots of My Dream Is Yours (1949), Tea for Two (1950), Lullaby of Broadway (1951), I’ll See You in My Dreams (1951) and April in Paris (1952), all named after the hit songs featured in the films. Far better were two charming, small-town period idylls, co-starring the clean-cut, handsome baritone Gordon MacRae: On Moonlight Bay (1951) and By the Light of the Silvery Moon (1953). Her pairing with Frank Sinatra in Young at Heart (1954) was more interesting as he was all scowls, she all smiles. It was a period during which she was voted by servicemen in Korea as “the girl we would most like to take a slow boat back to the States with.

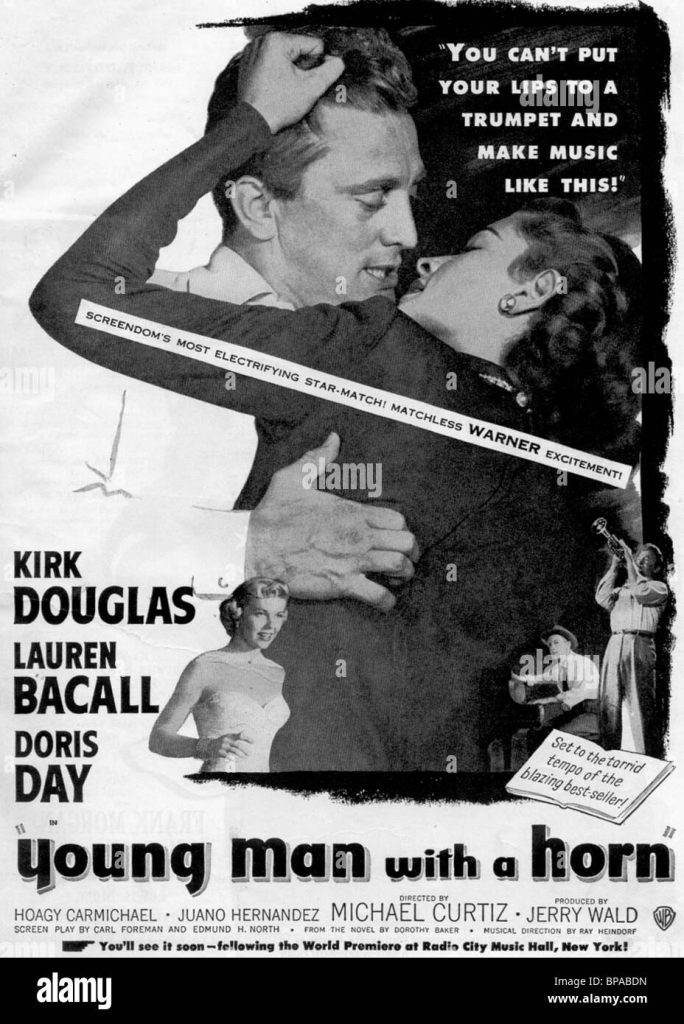

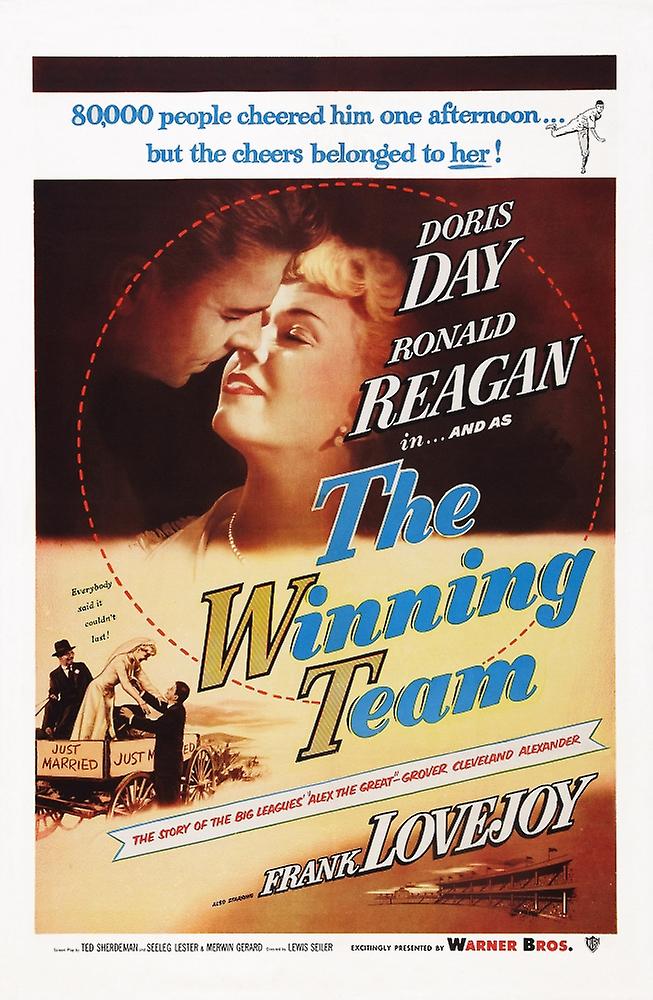

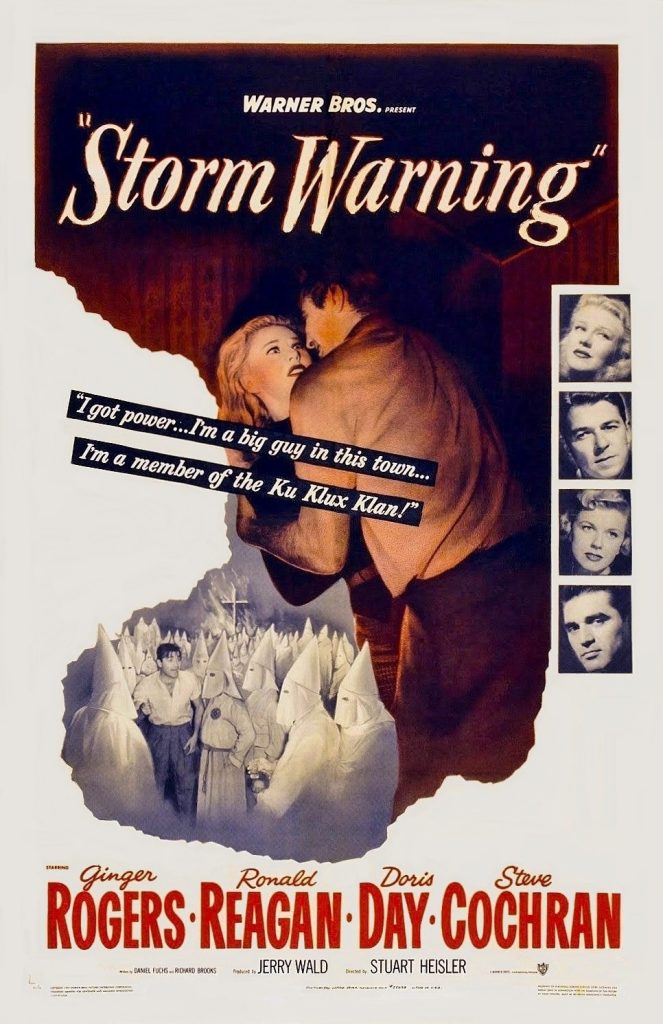

Day also handled a few dramatic roles with ease. She was the long-suffering girlfriend of a trumpeter (Kirk Douglas) in Young Man With a Horn (1950); Ginger Rogers’s sister in Storm Warning (1951), about a Ku Klux Klan murder; and wife of a baseball player (Ronald Reagan) in The Winning Team (1952), in which she laid on her charm thickly to compensate for his lack of it. (She and Reagan became friends and political allies.)

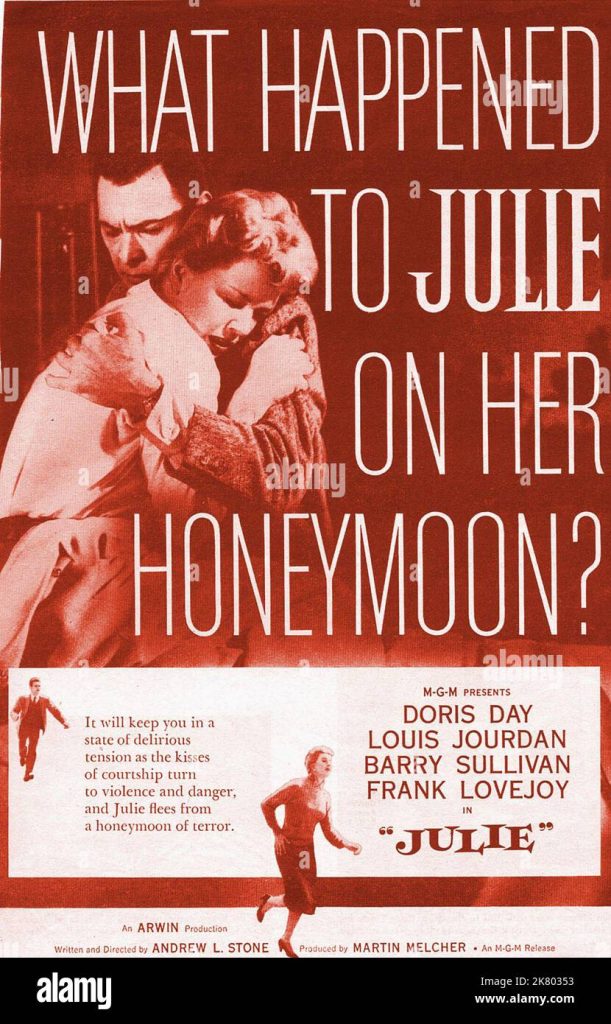

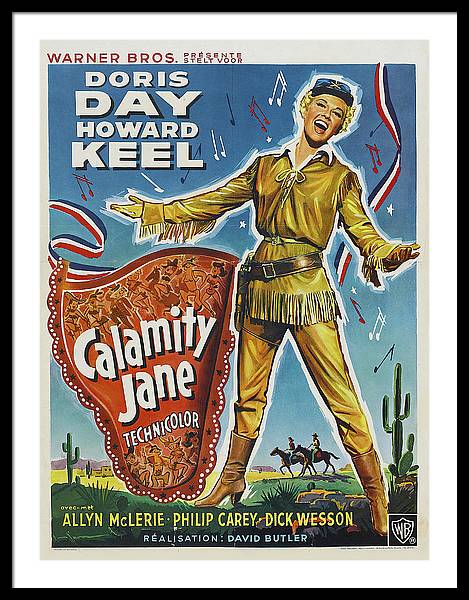

In 1951, Day married Marty Melcher, former talent scout and road manager of the Andrews Sisters. The couple formed a joint company, Arwin Productions, in 1952, which produced most of her films. The following year, Day gave one of her gutsiest performances as the wild west heroine Calamity Jane, touchingly warbling the Oscar-winning hit song Secret Love while leaning against a tree, then on horseback and at the top of the hill at the top of her voice. Wearing buckskins and toting a gun, she only emerged at the end from the chrysalis of tomboyhood into a butterfly of femininity in order to charm her “secret love”, Wild Bill Hickok (Howard Keel).

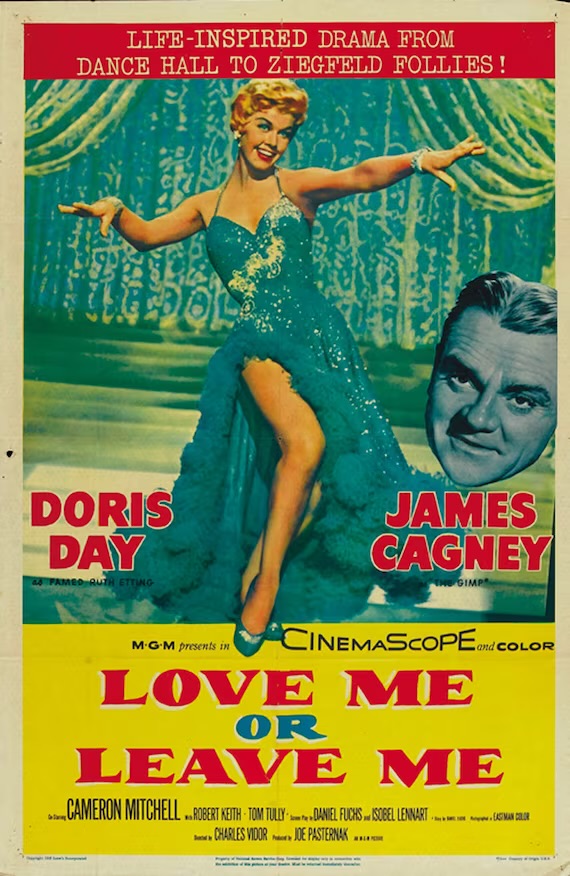

In contrast, looking more glamorous than ever, Day sang more than a dozen ballads (scored by Percy Faith) as the 20s torch singer Ruth Etting in Love Me Or Leave Me (1955), her first film for MGM. It was a musical worthy of her acting talents in which she matched James Cagney – as the abusive bootlegger gangster Moe “the Gimp” Snyder – blow-for-blow, line-for-line, drawing on her life experiences with men. The part was intended for Ava Gardner, but Gardner refused to have her singing dubbed. Etting, while obviously pleased with Day’s performance, denied she had ever been a dance-hall hostess as portrayed in the film, but acknowledged that it was a way of supplying context to the poignant song Ten Cents a Dance. After the film was released, Day was deluged with mail from fans attacking her, a Christian Scientist, for playing a woman who smoked, drank and wore scanty costumes.

Back at Warners, Day appeared in one of her liveliest musicals, The Pajama Game (1957), adapted from the Broadway show by George Abbott and Stanley Donen. Once again revealing more spice than sugar, she played “Babe” Williams, the dynamic head of the Union Grievance Committee of the Sleep-Tite Pajama Factory who falls for the foreman, despite belting out I’m Not at All in Love.

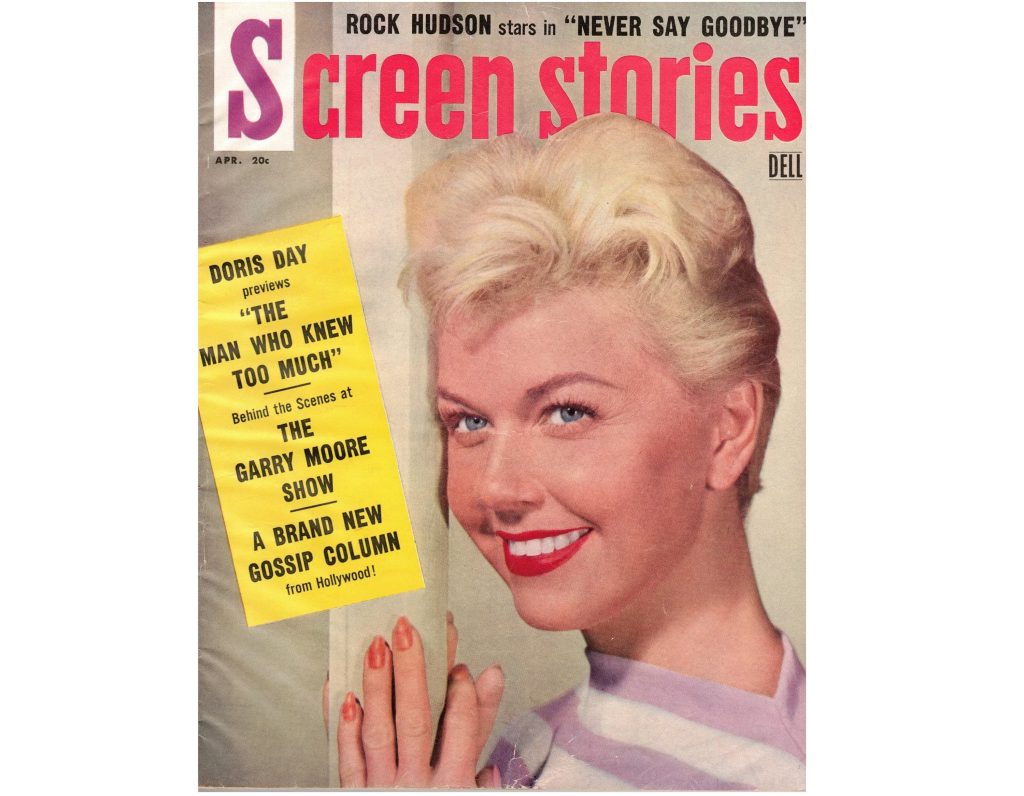

Day then had the “nerve-racking” experience of working for Alfred Hitchcock opposite James Stewart in The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956). “For each of my scenes there were dozens of takes, without Hitchcock saying one word,” Day remembered. “I said, ‘Mr Hitchcock what am I doing wrong?’ ‘If you weren’t doing it right, I’d tell you,’ he said.” Actually, all she had to do was look anxious for most of the time, and sing the Oscar-winning Que Sera, Sera (Whatever Will Be, Will Be) at a crucial moment in the film.

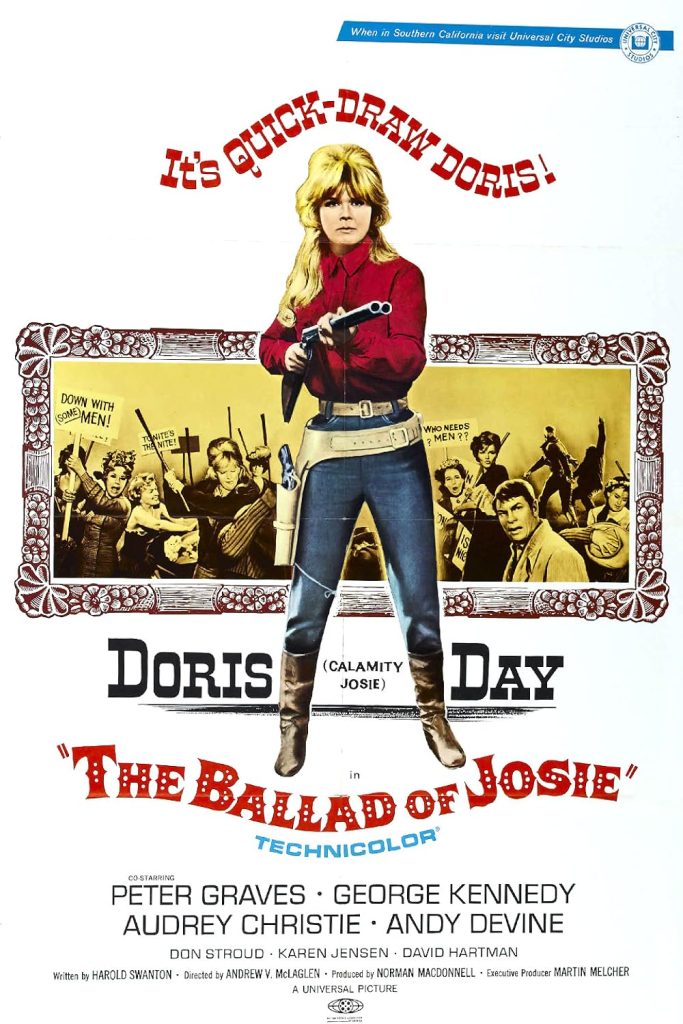

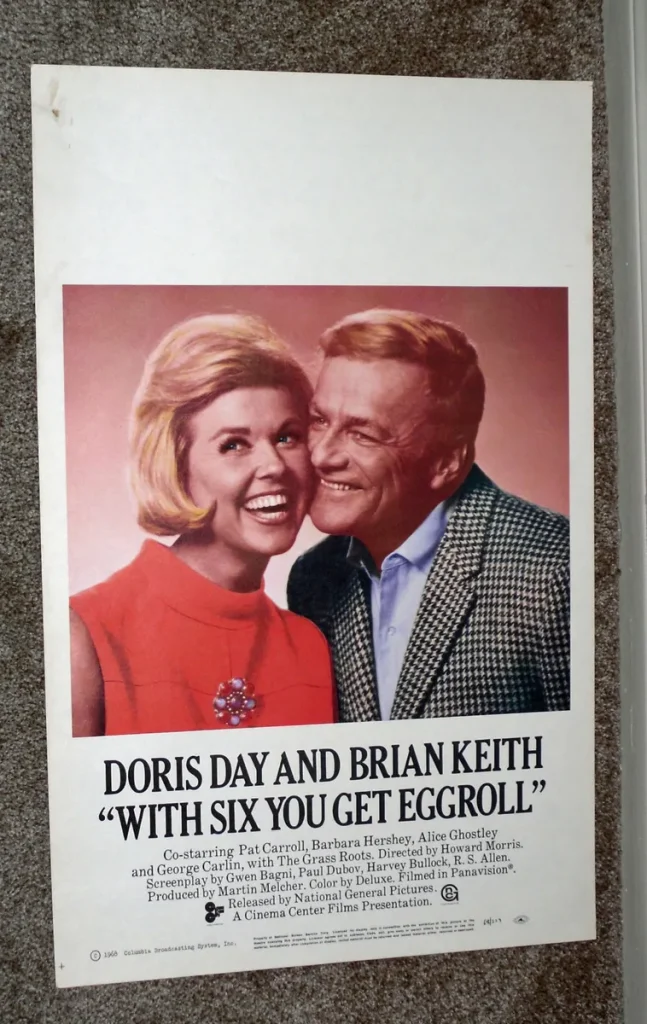

Day remained one of the top box-office stars, male or female, in the US throughout the 60s. She was also one of the highest-paid. However, in her late films The Ballad of Josie (1967), Caprice (1967) and, finally, With Six You Get Eggroll (1968), she failed to find roles that suited her age. It seems a pity that she refused Mike Nichols’s offer to play the seductive Mrs Robinson in The Graduate (1967), a plum role that went to Anne Bancroft. Day wrote: “I could not see myself rolling around in the sheets with a young man half my age whom I’d seduced. I realised it was an effective part, but it offended my sense of values.”

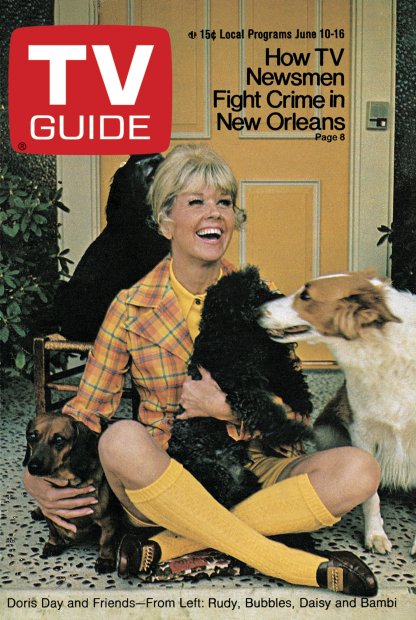

When Melcher died in 1968, it was revealed that he had squandered and embezzled most of Day’s money. After recovering from a nervous breakdown, she reluctantly hosted the Doris Day Show on TV for four years, a series that Melcher had contracted her to do without her knowledge. In 1974, she was awarded $22m in damages from the lawyer who had helped Melcher in the mismanagement of her business.

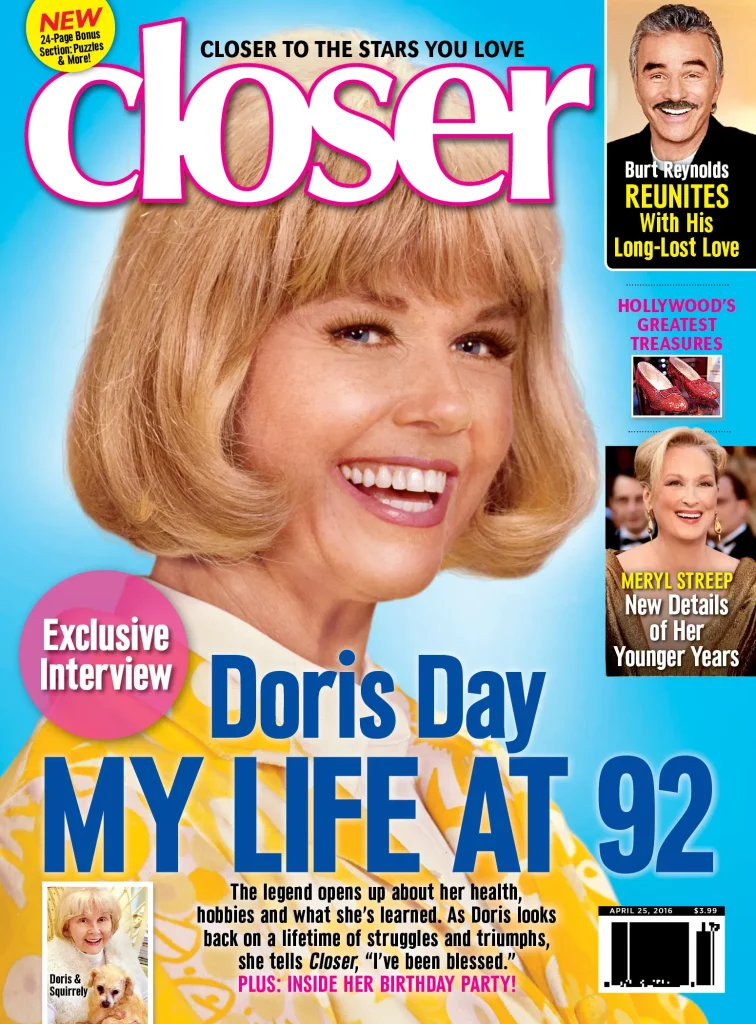

“Animals have never disappointed me,” Day once proclaimed. For decades after her retirement she devoted herself to animal welfare, founding various organisations including the Doris Day Animal Foundation. At her home in Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, she kept many dogs and cats, some of them former strays. Her fourth husband, Barry Comden, whom she married in 1976, complained that the main reason the marriage broke up in 1981 was because she cared for her animals more than him.

In 2011, Day released My Heart, a compilation of previously unreleased recordings. It was her first new album to be released in nearly two decades, and became a bestseller, proving her enduring popularity.

Day’s son Terry died in 2004.