Stella Stevens was born in Mississippi in 1938. She has some fine films to her credit including “The Nutty Professor” opposite Jerry Lewis in 1963, “Girls, Girls, Girls,” opposite Elvis Presley, “The Silencer” with Dean Martin and “The Ballad of Cable Hogue”. Perhaps her most famous movie is “The Poseidon Adventure” in 1972. Her son is the actor Andrew Stevens.

TCM Overview:

A popular screen siren of the early 1960s, actress Stella Stevens lent sex appeal to such popular light dramas and comedies as “The Courtship of Eddie’s Father” (1963) and “The Nutty Professor” (1964) before becoming a staple of TV and low-budget films for the next three decades. Though a talented actress, especially in gentle comedies, casting agents found it difficult to see past Stevens’ statuesque frame, which was the subject of three Playboy pictorials. Despite solid turns in Sam Peckinpah’s “The Ballad of Cable Hogue” (1970) as Jason Robards’ feisty lover and “The Poseidon Adventure” (1972), Stevens never found the proper vehicle for her abilities, and spent most of her time under the radar in episodic TV or genuinely awful films like “Monster in the Closet” (1986). Nevertheless, she continued to log appearances well into her seventh decade, which was a testimony to her professionalism, talent and apparent good humor.

Stella Stevens was born Estelle Caro Eggleston on Oct. 1, 1938, the only child of Thomas Ellett Eggleston and his wife, Dovey Estelle Caro. Sources frequently cited her birthplace as Hot Coffee, MS, but the moniker was simply a nickname for the town of Meridian, which lay near the Mississippi-Florida border. When Stevens was four, she moved with her family to Tennessee; there she met Herman Stephens, an electrician whom she married when she was just 15. A year later, she gave birth to her only child, future actor and producer Andrew Stevens. By 17, she had divorced Stephens, but kept a modified version of his surname for her professional career. While studying medicine at Memphis State College, she became interested in acting and modeling, and was reportedly discovered while appearing in a production of “Bus Stop” at the college. Stevens signed with 20th Century Fox, which provided her film debut with “Say One for Me” (1959), a modest musical starring and produced by Bing Crosby. For her minor turn as a chorus girl, Stevens shared the Golden Globe for Most Promising Newcomer – Female, with fellow up-and-comers Tuesday Weld, Angie Dickinson and Janet Muro.

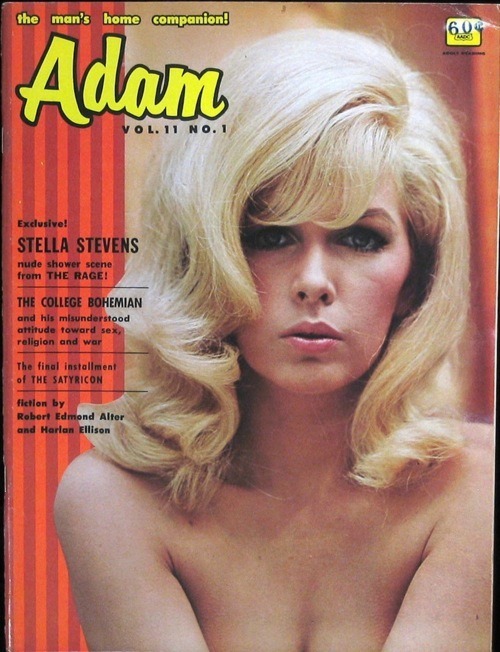

However, the promising start led to few subsequent opportunities, and Fox dropped her after six months. Stevens turned to the burgeoning gentleman’s magazine Playboy to boost her image, and in 1960, she became the publications Playmate of the Month for January. The layout, which tastefully revealed Stevens’ voluptuous frame, had the desired effect, and that year, she landed the role of Appassionata von Climax in the screen version of “L’il Abner” (1960). A steady stream of television appearances, magazine layouts and features soon followed, but most emphasized Stevens’ physical appeal rather than her talents. Occasionally, she received a solid vehicle for her acting skills, like “Too Late Blues” (1961), director John Cassavetes’ drama about a jazz musician (Bobby Darin) who abandoned his idealistic dreams for a sultry singer (Stevens).

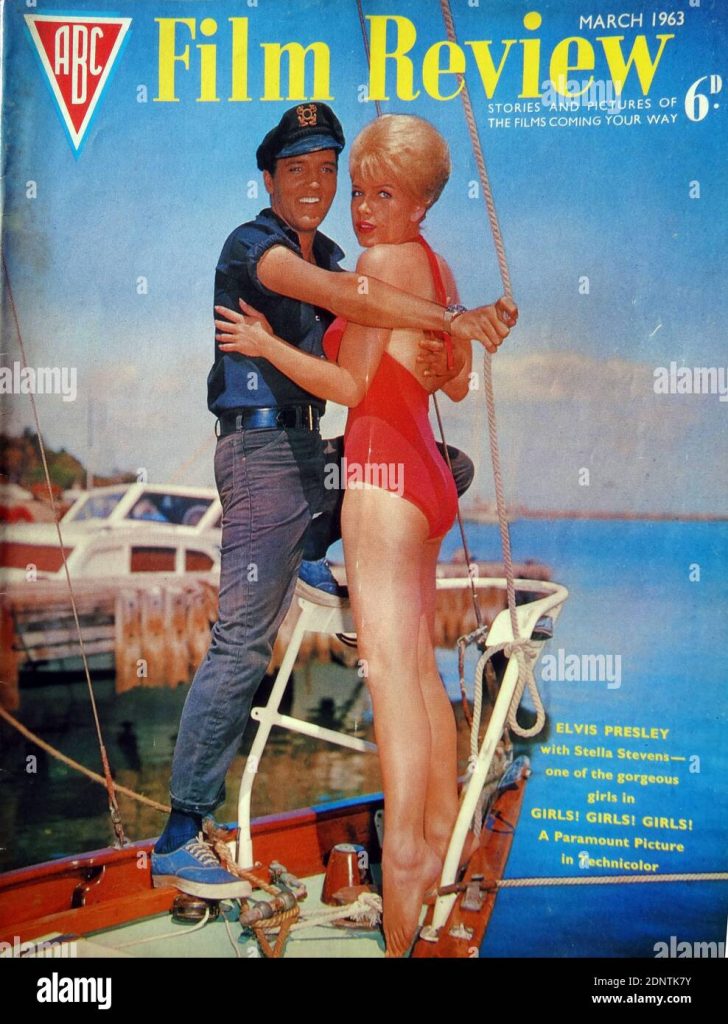

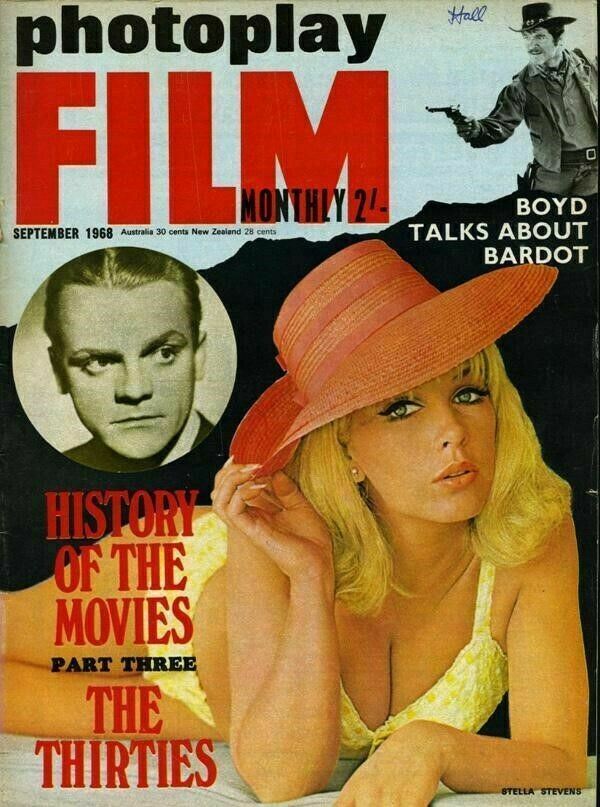

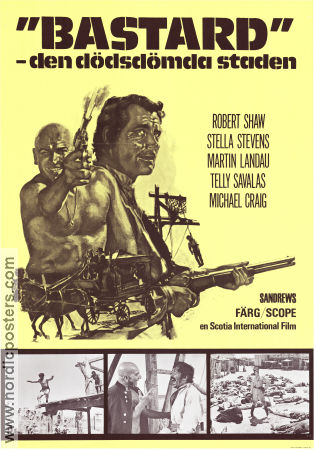

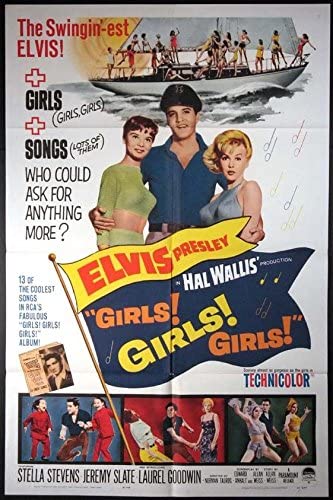

Stevens also had a particular gift for light comedy, as seen in her turns as a former beauty queen who caught Glenn Ford’s eye in “The Courtship of Eddie’s Father” (1963) and in particular, Jerry Lewis’ “The Nutty Professor” (1964), where she played the comely college girl who is wooed by the smooth Buddy Love, but saw the good in his alter ego, the hapless Professor Kelp. Despite these highlights, Stevens was found mostly in ornamental roles in features like “Girls! Girls! Girls!” (1962) with Elvis Presley, which she reportedly loathed and was forced to participate in, creating much friction between her and Paramount, and “The Silencers” (1966), one of the Matt Helm spy spoofs with Dean Martin. Stevens would return to Playboy for two subsequent layouts in 1965 and 1968 to help boost her visibility.

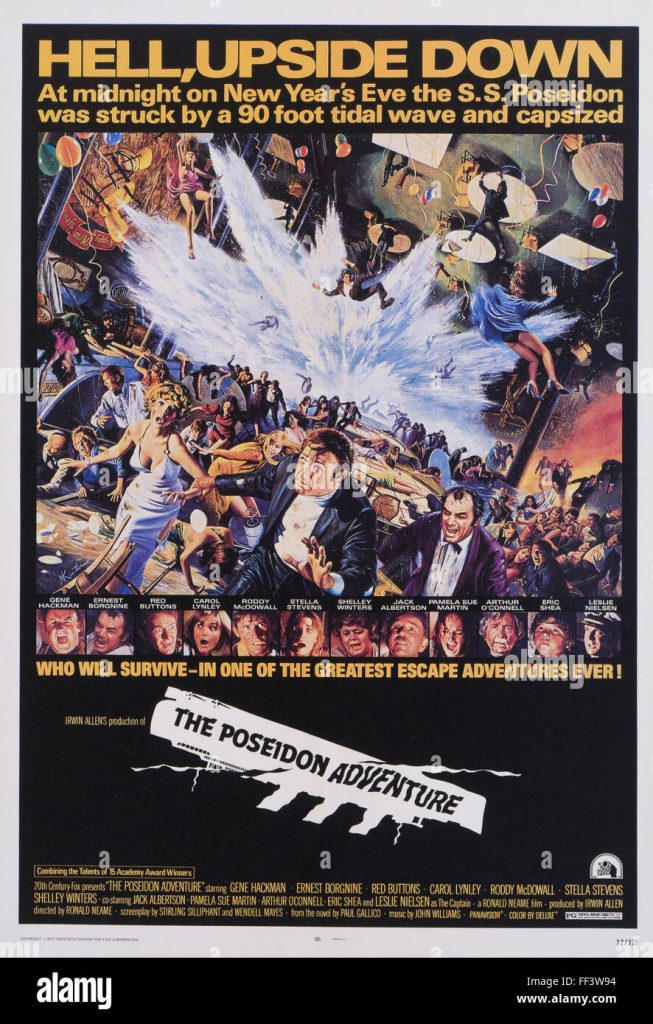

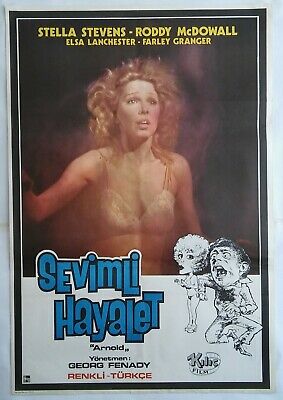

Stevens began the 1970s with critically praised turns in Sam Peckinpah’s “The Ballad of Cable Hogue” and “The Poseidon Adventure” (1972). In the former, she played a former prostitute who developed a tender romance with dogged cowboy Jason Robards, while in the latter, she was Ernest Borgnine’s determined ex-streetwalker wife, who survived most of the horrors of the sinking ocean liner, only to perish in the final reel. The pictures helped to solidify the idea that Stevens was more than an attractive figure, and she worked steadily throughout the decade on television and in features, though few were as high profile as her early efforts. By the late 1970s, she had resorted to B-pictures like “The Manitou” (1978), and eventually turned to television, where she co-starred on “Flamingo Road” (NBC, 1980-82) as a kindly madam who aided series lead John Beck. In 1979, she directed a feature length documentary called “The American Heroine,” about women from all walks of life, but the project was never released.

Stevens remained busy as she entered her fifth decade in the 1980s, though quality projects continued to elude actresses – particularly one-time sex symbols – of a certain age. She was a staple of episodic television, but her features had sunk to exploitative trash like “Chained Heat”(1983), a women-in-prison melodrama with Linda Blair, and direct-to-cable softcore efforts like “Body Chemistry III: Point of Seduction” (1994), many of which co-starred her son, Andrew Stevens. In 1989, he joined her for her second directorial effort, a low-budget comedy called “The Ranch,” about a city slicker who turned an inherited ranch into a spa. That same year, she joined the cast of the daytime soap opera “Santa Barbara” (NBC, 1983-1994) as star Robin Mattson’s troublemaking mother, Phyllis Blake. In the 1990s and 2000s, Stevens was a regular on television programs and in the occasional low-budget feature, though the 2004 horror film “Blessed,” produced by her son, was a rare exception. She published her first novel, Razzle Dazzle, in 1999 and launched a line of fragrances for men and women that, like her career itself, emphasized sexiness.

Stella Stevens died in Los Angeles in 2023 aged 84.

New York Times obituary in 2023.

By Clay Risen

Feb. 17, 2023

Stella Stevens, whose turn as an A-list actress in 1960s Hollywood placed her alongside sex symbols like Brigitte Bardot, Ann-Margret and Raquel Welch, but who came to resent the male-dominated industry that she felt thwarted her ambitions to be more than a pretty face, died on Friday at a hospice facility in Los Angeles. She was 84.

Her son, the producer and actor Andrew Stevens, said the cause was Alzheimer’s disease.

Ms. Stevens was among the last stars to emerge from Hollywood’s studio system, an arrangement that guaranteed her work but, she often said, also limited her creative aspirations. She won a Golden Globe in the “most promising newcomer” category for her role in “Say One for Me” (1959), a musical comedy starring Bing Crosby and Debbie Reynolds, but felt coerced into joining the cast of “Girls! Girls! Girls!” (1962), an empty Elvis Presley vehicle.

Like Ms. Welch, who died on Wednesday, Ms. Stevens was ambivalent, if not outright indignant, about being cast as a Hollywood sex symbol. She described herself as introverted and bookish, and she sought to work with auteurs like John Cassavetes, who cast her as the female lead in “Too Late Blues,” his 1961 drama about a jazz musician (played by Bobby Darin).

“I wanted to be a writer-director,” she told the film scholar Michael G. Ankerich in 1994. “All of a sudden I got sidetracked into being a sexpot. Once I was a ‘pot,’ there was nothing I could do. There was nothing legitimate I could do.”

She worked with many of the top directors and actors of the 1960s. She starred as the love interest of the title character, a timid college professor who undergoes a personality transformation, in “The Nutty Professor” (1963), which Jerry Lewis wrote, directed and starred in. She also had prominent roles in “The Courtship of Eddie’s Father” (1963), a romantic comedy directed by Vincente Minnelli, and “The Silencers” (1966), a spy spoof starring Dean Martin.

In between, though, she had to take a series of mediocre roles in mediocre movies, and critics came to view her as a star who was perpetually kept from realizing her full potential.

Two exceptions came in the early 1970s: She acted opposite Jason Robards in “The Ballad of Cable Hogue” (1970), a comic western directed by Sam Peckinpah, and as part of an all-star cast assembled for “The Poseidon Adventure” (1972), joining Ernest Borgnine, Shelley Winters, Gene Hackman and others in an overturned ocean liner.

By then her sex-symbol days were fading, and Ms. Stevens hoped to have the time and reputation to become a director. But female directors were almost unheard-of at the time, and her attempts to get support for what she called “a marvelous black comedy” she wanted to make met repeated dead ends.

“Every man I’ve gone to for four years has smiled at me and then double‐crossed me,” she told The New York Times in 1973. “Every man I’ve talked to in every office in this industry has tried his best to discourage me from directing. They don’t want me to find out it’s so easy because it’s supposed to be terribly hard.”

Stella Stevens was born Estelle Caro Eggleston on Oct. 1, 1938, in Yazoo City, Miss., though she often told interviewers she was from Hot Coffee, a nearby community. Her agent said anything sounded better than “Yazoo.”

Her father, Thomas, worked for a bottling company in Yazoo, and her mother, Estelle (Caro) Eggleston, was a nurse. When Stella was still young, they moved to Memphis, where her father worked in sales for International Harvester.

Stella dropped out of high school at 15 to marry Herman Stephens. They had one child, Andrew, and divorced in 1956. (She later changed her surname to Stevens because, she said, it was easier for people to pronounce.)

She returned to school after the divorce and, after earning a high school diploma, enrolled at Memphis State College, now the University of Memphis, with plans to become an obstetrician.

She also took up theater. A role in a college production of William Inge’s “Bus Stop” brought an invitation to audition in New York, and by 1959 she was in Los Angeles, on a three-year contract with 20th Century Fox.

She finished three movies in six months, including “Say One for Me,” but the studio dropped her soon after. With a young son to feed, she took an offer from Playboy to pose nude for $5,000. After the shoot, she said, Hugh Hefner, the magazine’s publisher, would pay her only half and told her that she had to work as a hostess at the Playboy Mansion to earn the rest.

Before the photos ran, she signed a new contract, with Paramount. She asked Mr. Hefner to cancel the magazine feature, but he refused, and she appeared as Playmate of the Month in the January 1960 issue, a few months before winning her Golden Globe.

“People don’t realize how horrible men can be toward a beautiful woman with no clothes on,” she told Delta magazine in 2010.

Her relationship with Playboy remained complicated. Despite her anger at Mr. Hefner, she posed nude for the magazine two more times. She then sued Mr. Hefner and Playboy in 1974, citing several instances of invasion of her privacy, but the case was thrown out because the statute of limitations had expired.

In 1998, Playboy named Ms. Stevens 27th on its list of the 20th century’s sexiest female stars, just behind Sharon Stone.

In addition to her son, Ms. Stevens is survived by three grandchildren. Her longtime partner, Bob Kulick, died in 2020.

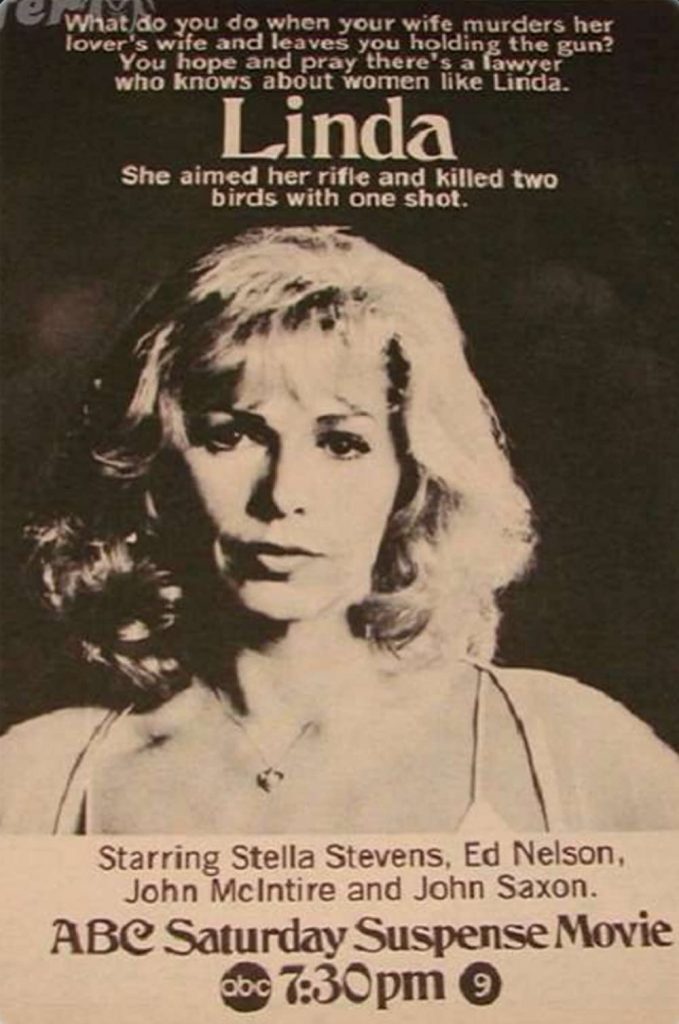

Despite her career’s post-1960s fade, Ms. Stevens remained eager to work. She turned to television and had roles in some 80 episodes over the next four decades. Most of them were guest appearances on shows like “Murder, She Wrote,” “The Love Boat” and “Magnum P.I.,” though she was also a member of the regular cast of several shows, including the soap opera “Santa Barbara.”

When she did return to film, it was often for soft-core erotic thrillers and campy horror movies. In “Chained Heat” (1983), she played a prison warden; in “The Granny” (1995), she played a wronged grandmother who comes back to life to get revenge on her scheming family.

She eventually did get into the director’s chair, for “American Heroine,” a 1979 documentary, and “The Ranch,” a 1989 comedy starring her son. She also wrote a novel, “Razzle Dazzle” (1989), which featured a thinly fictionalized version of herself.

“I don’t feel I’ve been successful yet,” she told The Vancouver Sun in 1998. “I’m still waiting to be discovered. I see myself as a work in progress. I keep trying to work and improve and do things I’m proud of.”