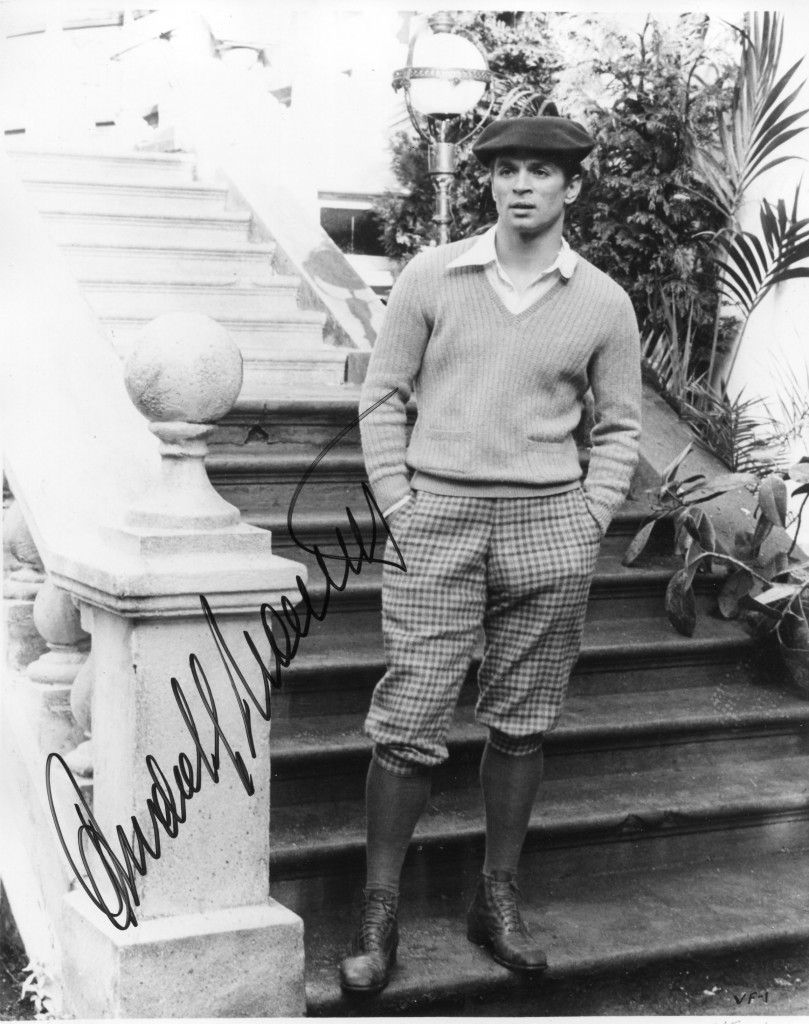

The great Russian dancer Rudolf Nureyev was born in 1938 in Irkutsk. A famed dancer with the Kirov Ballet, he defected from the Soviet Union in 1961 and formed a highly successful ballet duo with Dame Margot Fonteyn. In the 1970’s be began making movies and hat the title role in Ken Russell’s “Valentino” in 1977 and “Exposed” in 1983. He died in 1993.

TCM overview:

One of the most celebrated dancers of the 20th century, Rudolf Khametovich Nureyev displayed an artistically expressive skill that combined classical ballet and modern dance and changed the perception of male ballet dancers. He was born on March 17, 1938 while his mother Feride was aboard a Trans-Siberian train. He spent most of childhood and youth in Ufa, the capital of the Soviet Republic of Bashkir. From his earliest days, the young Nureyev loved music. When his mother snuck him and his siblings to a performance featuring ballerina Zaituna Nasretdinova, it was the tipping point for Nureyev to pursue a life in dancing. He began taking dance lessons and eventually enrolled at the Kirov Ballet’s Leningrad Choreographic School in 1955 at the age of 17. He trained under the legendary ballet teacher Alexander Pushkin, who also taught Mikhail Baryshnikov. He quickly became a sensation in the Soviet Union, having danced 15 roles within his three years at the Kirov Ballet. However, the Soviet Union’s stifling protectiveness over one of its cultural icons became too much for the headstrong Nureyev. On June 16, 1961 Nureyev flew to Paris and defected from the Soviet Union. Now unfettered by the USSR’s communist regime, Nureyev signed up for the Grand Ballet du Marquis Cuevas and continued to tour all over Europe, which ensured that his career and recognition would turn international. He made his first appearance in the United Kingdom when he danced Poeme Tragique, a solo choreographed by renowned British dancer Frederick Ashton, and the Black Swan pas de deux. In 1962, The Royal Ballet founder Dame Ninette de Valois offered him to join her company as Principal Dancer; he stayed there until 1970. Aside from his numerous stage performances, Nureyev shared his elegant dance forms in several films. He made his screen debut in a film version of “Les Sylphides” (1962). Nureyev made his directorial debut in a film version of Sir Robert Helpmann’s production of “Don Quixote” (1972). Nureyev was one of the first guest stars of “The Muppet Show” (syndicated 1976-1981) when it was still a fledgling show, and his appearance was often credited with turning the Jim Henson series as one of the most sought after programs for other celebrities to appear in. In his later years, Nureyev was appointed director of the Paris Opera Ballet in 1983, and continued to dance and teach younger dancers. Unfortunately, Nureyev was one of the earliest victims of the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s. He tested positive for HIV in 1984, but continued to remain active in the dance scene. He was allowed to return to his native country for the first time since his defection to visit his dying mother in 1987. Two years later, he was invited to dance the role of James in “La Sylphide.” As his illness began to enter its final and ultimately fatal stages, Nureyev began to suffer several medical problems. His last public appearance was on October 8, 1992 at the premiere of “La Bayadere” at Palais Garnier. Nureyev succumbed to his medical complications on January 6, 1993 at the age of 54. Although Nureyev’s life was tragically cut short, his influence on ballet and modern dance was an everlasting legacy.

Barry Joule’s obituary in “The Independent”:

At the beginning of the year, we saw him off from London to conduct in Vienna, and several other European stops, before a substantial tour in Russia. In mid-March he fell extremely ill in St Petersburg. Against the Russian doctors’ advice, and by sheer Tartar will-power, he forced himself out of hospital, on to a plane to Paris and home.

Dr Michel Canesi was for 10 years Rudolf’s doctor and friend. Canesi is one of France’s leading experts on Aids and affiliated with the private Hopital du Perpetual Secours in north Paris. It was here, from Spring 1992 until his death, between bursts of creativity and travel, that Rudolf was a regular patient under an assumed name, being treated for complications of HIV infection.

By mid-April he had rallied and, taking a nurse he liked, he left hospital to go to New York. Here he was to conduct Romeo and Juliette for the American Ballet Theatre. Saddled with two hours of medical treatment every morning, he still found time to learn the score and direct the company.

On 6 May, from the galleries of the Metropolitan Opera House confetti snowed down. The maestro had scored brilliantly; the New Yorkers always loved their favourite dancer from the time he and Margot Fonteyn stormed in in the Sixties. Rudolf never stayed to read his critique, but left for his farm in Virginia. Then it was back to Washington for a celebration and a plane south to his seaside bungalow on the French island of St Barthelemy. June saw him in San Francisco, New York, then back to Paris.

Only a handful of his closest friends knew of his debilitating affliction. Each day was more difficult, more of a drain on his enormous reservoirs of strength. In mid-July he went to the islands of Galli he owned south of Capri. Here, in the heat he adored, he was happiest.

By the beginning of August he had weakened a good deal, yet denied anything was really wrong. We went from Galli to Naples to pick up a brand new yacht which he had just bought, which was christened Tartara after the Prince of Dance.

At the beginning of September a helicopter was called to take him off the island. Back in Paris he received urgent medical treatment, and gamefully plunged into rehearsals for La Bayadere, which was set to open the Paris season in October. He was to choreograph and conduct one of his favourite ballets, which he had danced as a teenager at the Kirov. His old dancing partner from the Kirov Ninel Kourgapkina, 62, came over to assist him, and his Parisian friends rallied round to help.

In mid-September I moved into his apartment, opposite the Louvre, and stayed with him until after the Gala. The long days were arduous for this once superb athlete. There were medical treatments at home, trips to the hospital, pills to be swallowed around the clock, drips etc. But every night at 6pm sharp he somehow found the energy to go to the Opera.

He fell over on his first night, in front of the entire company. They were aghast, riveted to the spot, until he barked, ‘What are you looking at? Get on with it.’ A sofa was provided at the side of the stage and every night from this vantage point he watched, his searching eye never missing a detail. Everyone danced their hearts out; it was awe-inspiring to watch this great drama unfold. Rudolf was furious when Dr Canesi told me what we all knew: that he was too weak to conduct.

Exhausted, each night we returned home, where Rudolf would collapse into his bed. He was a complete professional to the tips of his powerful toes. I learnt this yet again when on 3 October his dearest friend, Maude Gosling, arrived from London. It was after midnight and we had just returned to his apartment after an especially long, difficult, rehearsal. After settling him in bed I told him, both Maude and Ninel were waiting to see him, ‘Who shall I send in first?’ ‘Ballet business first,’ he said, ‘send in Ninel.’

The opening gala was a sensation. From beside the stage he watched the ballet from his sofa. Afterwards, the tears flowed freely everywhere and he shakily took his 15 minutes of applause, supported by the ballerinas.

Previously we had discussed if he wanted to take his award on stage and attend the gala supper. The risks were that the spotlights would make his still-secret illness apparent. He said simply, ‘Show goes on.’ After the awards a sumptuous meal in the west wing of the Opera was under way when Rudolf took his place at the head table. After the first course Pierre Berge, Chairman of the Opera, found me to say Rudolf must leave immediately. Together, arm in arm, while the 600 guests rose, most weeping and clapping for their ailing star, we led him out.

After three days he had recovered a bit and was determined to fly to the sunshine for a last time. Against doctors’ order he returned to ‘St Barts’. He was back in Paris at the beginning of November; the illness had taken a frightful toll. But, although he was a shell of his former self, the ideas and plans still tumbled out of his prodigious mind. I finally saw him just after Christmas propped up on pillows in his hospital bed. He did not recognise me, but his favourite Bach was playing and one of his painfully thin arms was slowly moving in the air, as if he was rehearsing for some future concert.