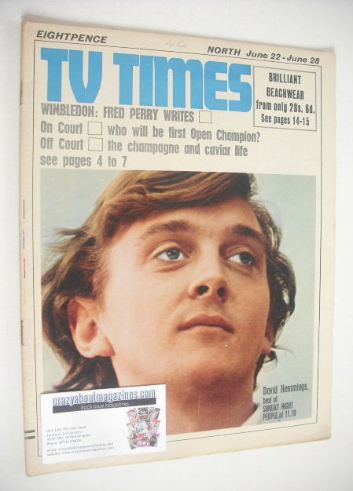

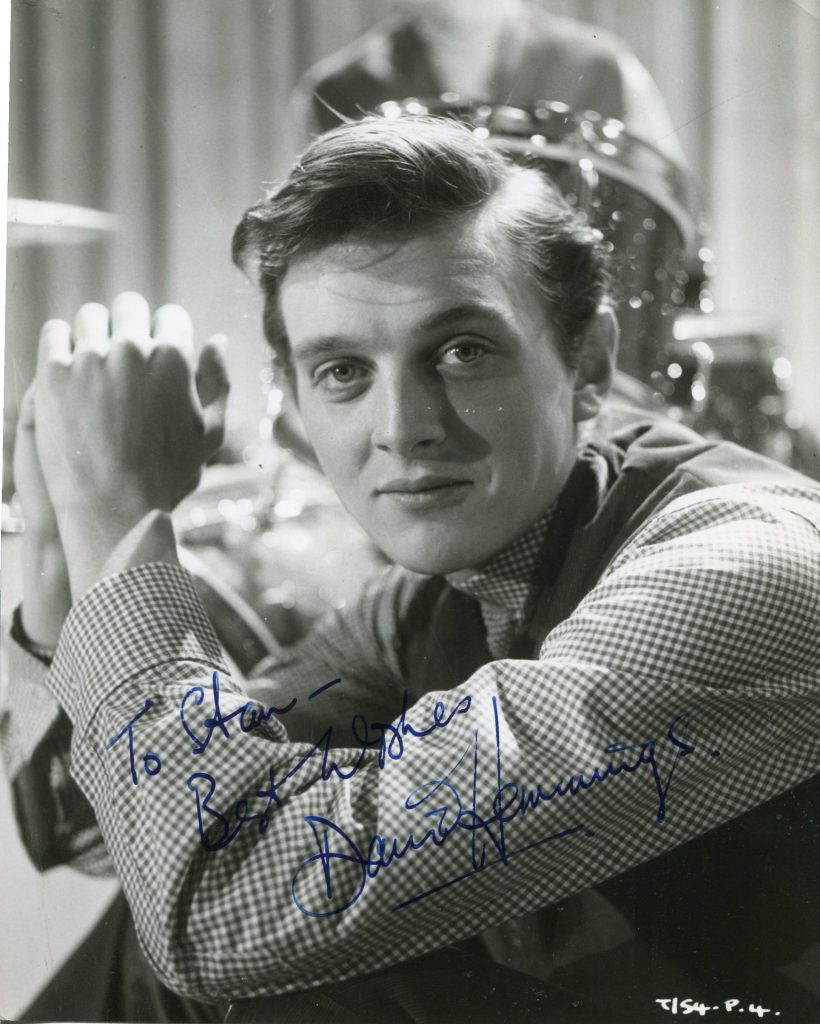

David Hemmings came to international fame with his central performance in the 1966 film “Blow Up” which represented Swinging London of the 1960’s. He went on to star in such movies as “The Charge of the Light Brigade” and “Alfred the Great”. His last performance was in “The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen”. He died suddenly while on location in Budapest in 2003. He was 62 years old.

“The Guardian” obituary by Tim Pulleine:

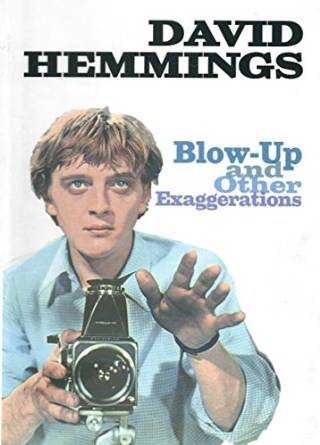

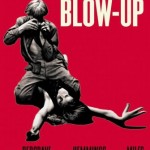

David Hemmings, who has died suddenly aged 62 following a heart attack while filming Samantha’s Child in Romania, had a long and varied screen career as an actor, director and producer. But he will be remembered, above all, for his performance in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film Blow Up, that defining reflection on the swinging 60s in which the Hemmings character – a fashionable photographer reportedly based on David Bailey – is eventually brought face to face with the illusoriness not only of success but of reality itself.

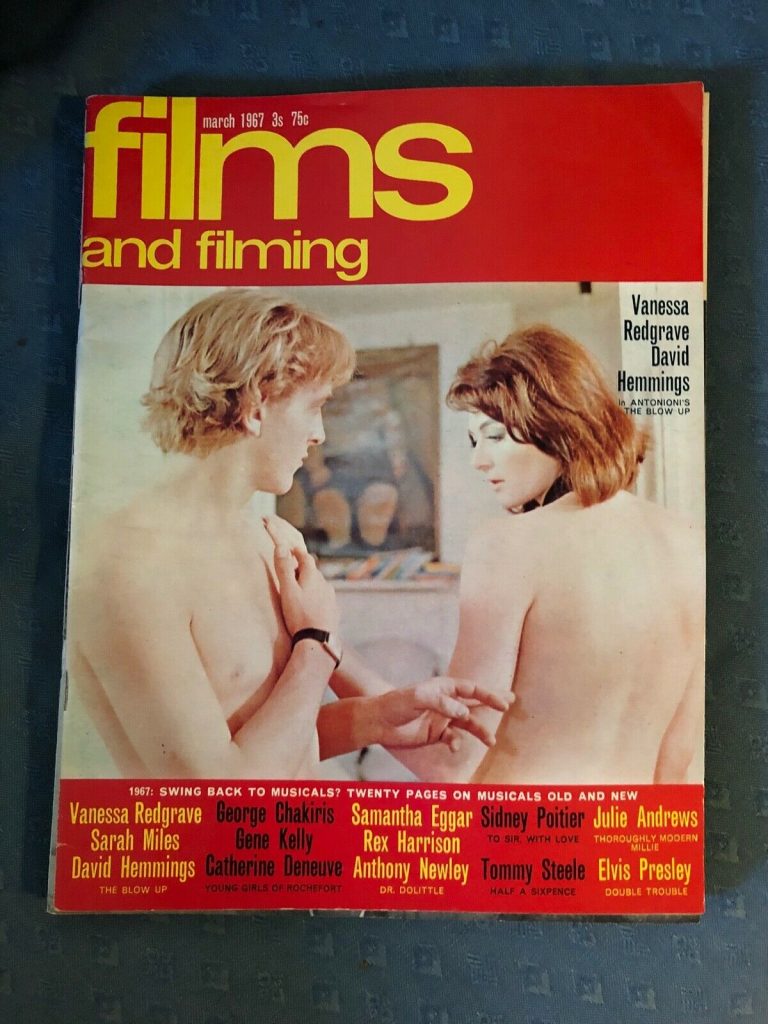

The film’s conclusion, in which the photographer is gradually torn into participation in an imaginary game of tennis, must surely rank as one of the most mesmerising in all cinema. Hemmings’s physical demeanour, combining down-to-earth chippiness with an almost ethereal air of fragility, admirably embodied the themes of a groundbreaking movie, which dissolved the barriers between art and popular cinema.

His co-star list in Blow Up also said much about the talented pool of actors then available to British cinema – Vanessa Redgrave, Sarah Miles, Jane Birkin, Varuschka and Peter Bowles, who became Hemmings’s best friend in the years to come.

Born in Guildford, Surrey, and educated at Glyn College, Epsom, Hemmings had, in fact, begun as a child actor, as well as having been a notable boy soprano, and featuring in English Opera Group performances of the works of Benjamin Britten. After his voice broke, he studied painting at Epsom School of Art, where he staged his first exhibition at the age of 15. He returned to singing in his early 20s, making nightclub appearances before moving on to the stage and gradually into movies.

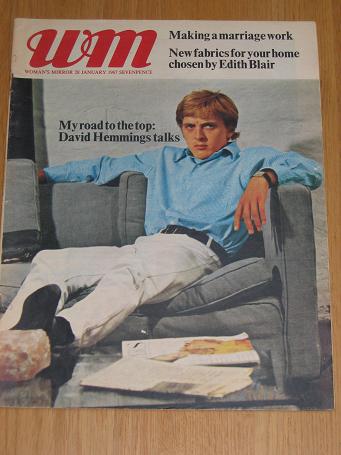

He first appeared in films as early as 1954, with the Ealing Studios production of The Rainbow Jacket, and took a small role in Otto Preminger’s 1957 version of St Joan. By the turn of the next decade, he was just the right age – and of the right tousled, contemporary appearance – to represent the then burgeoning youth culture on the screen.

Thus he was in pop music quickies like Live It Up (1963) and, more substantially, in an early Michael Winner movie about a group of layabouts in a seaside town, The System (1964), co-starring with Oliver Reed. Hemmings and Reed were, in a sense, the yin and yang of that era’s characteristic look: Hemmings blond and slight, Reed dark and brooding. Nearly 40 years on, by odd coincidence, both men were to appear in Gladiator (2000), during the filming of which Reed died (obituary, May 3 1999).

The acclaim visited upon Blow Up converted Hemmings into an international name and an exemplar of the supposedly liberated alternative culture. But despite appearing alongside Jane Fonda in Roger Vadim’s pop art fantasy Barbarella (1968), he resisted any too ready identification of this kind, notably by playing in two ambitious historical movies, as the ill-fated Captain Nolan in The Charge Of The Light Brigade (1968) and taking the title role of the somewhat misconceived Alfred The Great (1969). Both films sought, it should be said, to tap into the counter-cultural attitudes of the time in which they were made, partly via the presence of Hemmings himself.

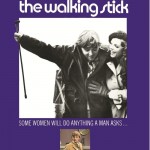

In 1972, Hemmings ventured into directing, taking on the suspense thriller Running Scared, in which the chief role was played by Gayle Hunnicutt, his wife from 1968 to 1974, and with whom he had earlier co-starred in Fragment Of Fear (1970). Running Scared, which Hemmings also co-scripted with Clive Exton, was an ambitious, if ultimately flawed, exercise in psychological tension, made in an elliptical narrative style seemingly influenced by Antonioni.

The following year, he directed a more avowedly offbeat picture, The 14, a strange tale, inspired by fact, of a misfit family of four children and their vicissitudes in the wake of their single mother’s demise. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it failed to achieve wide popularity.

Hemmings also formed, with his business partner, John Daly, the Hemdale Corporation, which for some years became a significant force in film production and distribution. But while assuming an executive profile, he continued to appear in front of the camera, sometimes in rather unexpected contexts, such as that of the Italian horror movie Profondo Rosso (1976). His other film roles during the decade were as varied as an upright bomb disposal officer in Juggernaut (1974) and a scheming criminal in The Squeeze (1977).

By the 1980s, however, television work had taken precedence, and he was to be found directing such shows as Magnum PI, Airwolf, The A-Team and Quantum Leap.

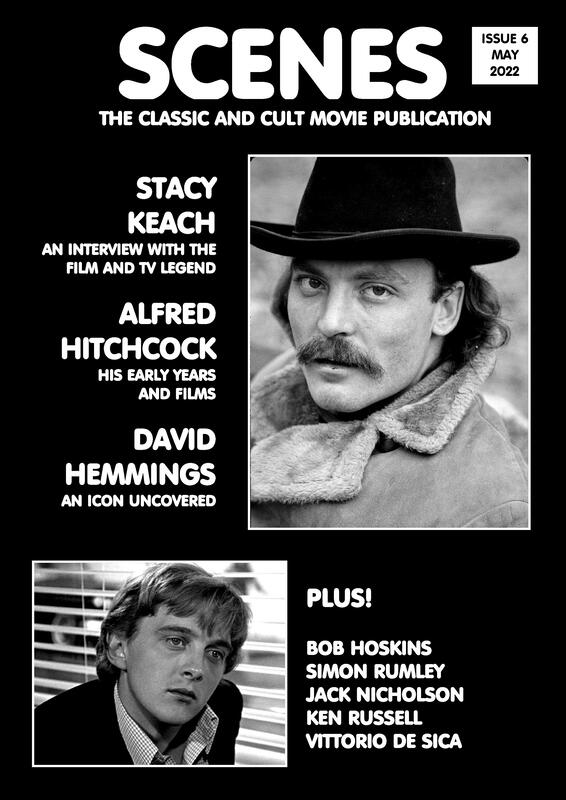

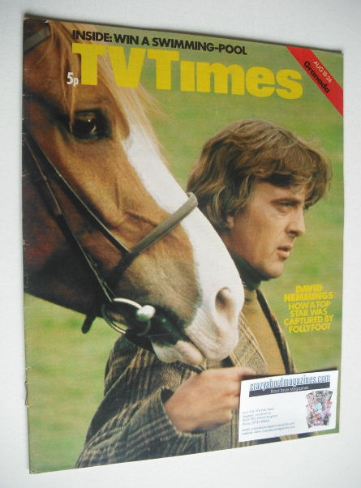

Gradually, in fact – and adeptly – Hemmings was shading, as he approached middle age and became physically bulkier, into the domain of the character actor. He gave, for instance, a notable performance as a hardbitten and vindictive policeman, doing his best to frame a suspect, in the New Zealand-made Beyond Reasonable Doubt (1980) – a part in which he embodied a malign authority figure startlingly in contrast to the iconoclastic youthfulness with which he had been identified in earlier times.

The following year, also in New Zealand, he directed and produced a rip-roaring buried treasure yarn, Race For The Yankee Zephyr, again affording conspicuous contrast with the psychological inflections of Running Scared.

It cannot be claimed that, in more recent years, Hemmings maintained a very consistent screen presence, although he continued to be active. Such roles as the colliery owner in Ken Russell’s 1989 film of DH Lawrence’s The Rainbow offered no very great opportunity, and directorial ventures like The Dark Horse (1991) seem not to have been widely seen.

However, there was Cassius, in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator, The League Of Extraorinary Gentlemen (2003) and, more memorably, his appearance in the film version of Graham Swift’s elegiac novel Last Orders (2001), about a group of friends travelling to the seaside to dispose of the ashes of the first of their number to die. The presence of Hemmings – along with other such actors as Michael Caine and Tom Courtenay, who also made their reputations in the new wave British cinema of the 1960s – gave tangible presence to the themes of mortality and changing times. Hemmings’s characterisation of cheery ruefulness in the face of ageing seems all the more plangent in the light of his own early death.

In an interview with the Guardian two years ago, Hemmings was asked if he would still like to direct movies. “Never say never, but I will never direct again,” he replied. “I’m back from America, and I think the time has come to say that all those wonderful Malibu parties are behind me. I have no ambitions, except to paint. I live in a market town, in a mill house with the river running both sides and Somerfield’s car park only a loose nine-iron away, and I really, really, really, love it.”

He is survived by his wife Lucy; a daughter Deborah by his first marriage to Genista Ouvry; a son Nolan by his marriage to Gayle Hunnicutt; and four children, George, Edward, Charlotte and William, by his third marriage, to Prudence J de Casembroot.

· David Leslie Edward Hemmings, actor, director and producer, born November 18 1941; died December 3 2003

To view “The Guardian” Obituary, please click here.