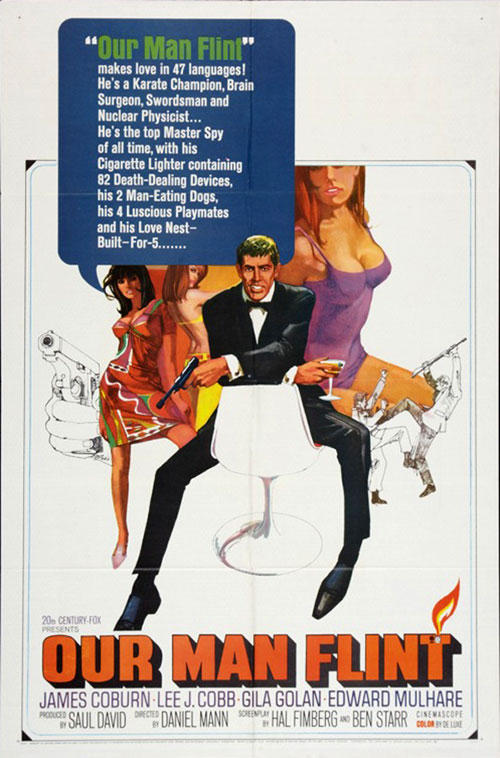

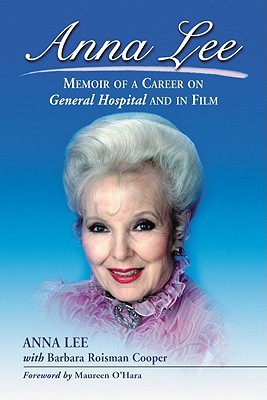

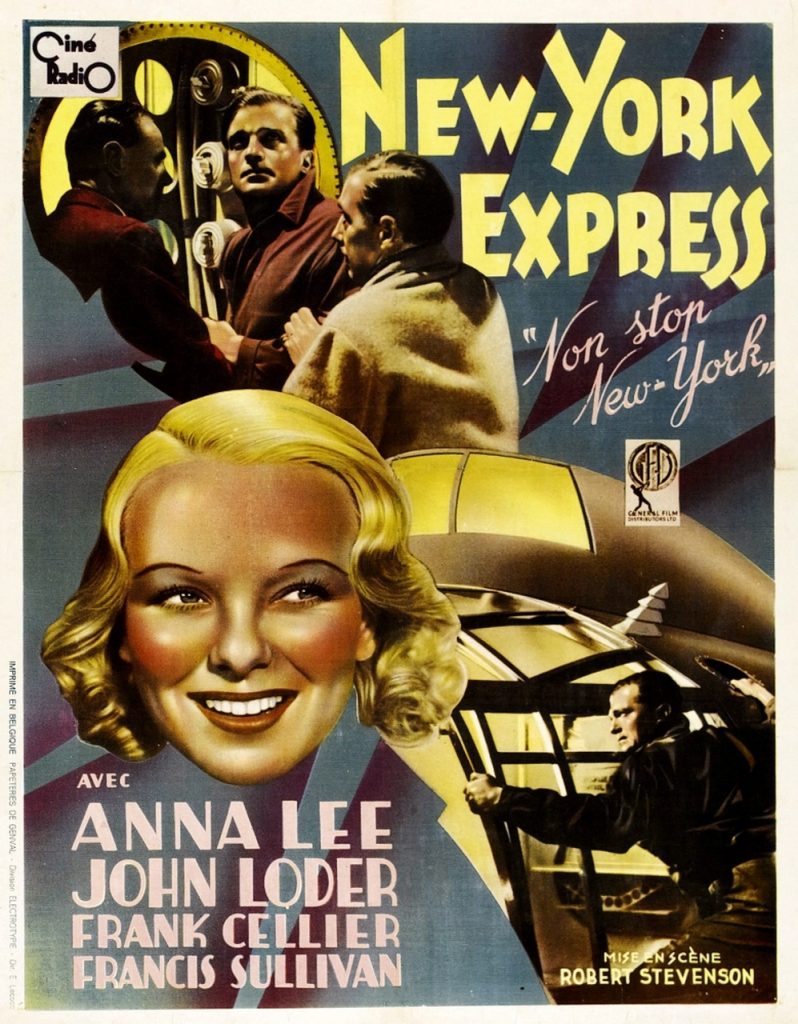

Anna Lee was born in Kent in 1913. She began her career in 1930’s British movies such as “King Solamon’s Mines” with Paul Robson in 1937 and “Non-Stop New York”. In the late 1930’s she and her husband the film director Robert Stevenson went to Hollywood and she made many movies with John Ford, including “How Green Was My Valley” in 1941, “Ford Apache” in 1948, “The Horse Soldiers” in 1959 and 2Seven Women” in 1965. Her other movies include “Bedlam”, “The Ghost and Mrs Muir”, “The Sound of Music” and “Our Man Flint”. She starred in the long running TV soap “General Hospital” from 1978 until 2004. She died at the age of 91 in 2004.

Richard Chatten’s obituary on Anna Lee in “The Independent”:

Spirited, extremely pretty and a natural blonde, but far too refined and school-marmish for standard Hollywood stardom (the playwright Bertolt Brecht, with characteristic gallantry, dismissed her as “a smooth, characterless doll”), it would be rash to make any great claims on Anna Lee’s behalf as an actress, but it was always a pleasure to see her and she could be very effective when well cast.

In Hollywood (after inventing an Irish grandfather to win his approval) she became one of the few female members of fellow Catholic John Ford’s regular repertory company of actors, appearing in eight of his films between How Green Was My Valley (1941) and7 Women (1966). The parts that he gave her seldom amounted to very much, however, and it perversely fell to two of Hollywood’s most macho, off-beat talents to provide her with two of her best middle-aged roles.

In Sam Fuller’s The Crimson Kimono (1959), she played Mac, the drunken, cigar-smoking Bohemian artist and earth-mother to the heroine (in whom her interest may be more than purely maternal), and in Robert Aldrich’s What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), she was the breezy neighbour of Joan Crawford and Bette Davis, who by her example allayed fears that women of her age inevitably disintegrated into Gorgons like those living next door. After shooting their first scene together, Davis barked, “It’s good to be working with a pro.”

Born Joan Boniface Winnifrith in Ightham, Kent, in 1913, daughter of the village rector, and god-daughter of Sybil Thorndike, her stage name was a composite of Anna Karenina and Robert E. Lee. She made her début on the London stage in 1932 and, a few minor film appearances later, was promoted to Jack Hulbert’s leading lady – an intrepid young aviatrix – in The Camels are Coming (1934).

Her vigorous, try-anything personality also saw service as assistant to mad scientist Boris Karloff in The Man Who Changed His Mind(1936), Allan Quartermain’s daughter in King Solomon’s Mines(1937) and a human cannonball in Young Man’s Fancy (1939), during the filming of which she was actually shot out of the cannon.

All three were directed by her then-husband Robert Stevenson, who directed most of her films at this time, and whom she accompanied to Hollywood in 1939. She was also the second lead, Jessie Matthews’ platinum blonde rival, in First a Girl (1935), a part, alas, that was to prove more characteristic of what was to come her way after transferring to Tinseltown, although she started at the top, co- starring opposite Ronald Colman in My Life With Caroline (1941).

It was a dreary film, however, and after a few undistinguished female leads in quality productions like Commandos Strike at Dawn(1942) and Hangmen Also Die (1943), she was rapidly relegated to supporting roles in “A” features such as Flesh and Fantasy (1943),Summer Storm (1944), The Ghost and Mrs Muir (1947) and Fort Apache (1948), and leads in “B”s. Ironically, it was one of the latter that gave her her best part (and, after How Green Was My Valley, her own personal favourite) – that of Nell Rowen in Val Lewton’sBedlam (1946), a frivolous young actress whose wilfulness provokes her sugar daddy into having her placed in the care of a leering asylum director played by Boris Karloff.

She returned briefly to the stage in 1950 in a summer stock tour ofMiranda and began increasingly to appear on television, including a three-year stint during the early Fifties as a panellist on It’s News to Me.

At this point, however, her career was abruptly interrupted by the Hollywood blacklist. Although in her own words a “Winston Churchill Conservative”, who saw nothing wrong with the blacklisting of actual Communists, she was confused with another actress and her name appeared in the notorious anti-Communist newsletter Red Channels. She was unable to get acting work for several years and was forced to make her living writing TV scripts under an assumed name.

In 1956 she finally wrote in desperation to Ford, who immediately got on the phone to Washington and cleared the situation up. “If it hadn’t been for Ford, I probably wouldn’t have been working now,” she told the film historian Joseph McBride in 1987, but even so, she still had to add a rider to every contract she subsequently signed declaring that she was not now, and had never been, a Communist.

It was Ford who made her rehabitilition complete by giving Lee her first film role since 1952, as Mrs Jack Hawkins in Gideon’s Day(1958, her only post-war British film), and later film roles included a stagecoach passenger held up by Lee Marvin in Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Balance (1962) and a nun with a twinkle in her eye inThe Sound of Music (1965).

Her last substantial film role was in In Like Flint (1967) in which, to quote Variety‘s reviewer, “Anna Lee, ever a charming and gracious screen personality, is part of a triumvirate bent on seizing world power.” (The trouser suit she wore throughout the film concealed the fact that she was black and blue from head to foot and had a broken wrist and 13 stitches in her thigh from a car accident four days before shooting had started).

Throughout the Eighties and Nineties she regularly featured, still as pretty as ever, in the soap opera General Hospital, only retiring from the show last year. A year after she had joined in 1978, taking the part of Lila Quatermaine, she was paralysed from the waist downwards in a car accident, and acted the role in a wheelchair.

She had a narrow escape just before Christmas 1994 when she was hauled to safety as her cottage off Sunset Strip caved in behind her during a fire which also destroyed most of her memorabilia and the only draft of her autobiography.

Richard Chatten

The “Independent” obituary can also be accessed on-line here.