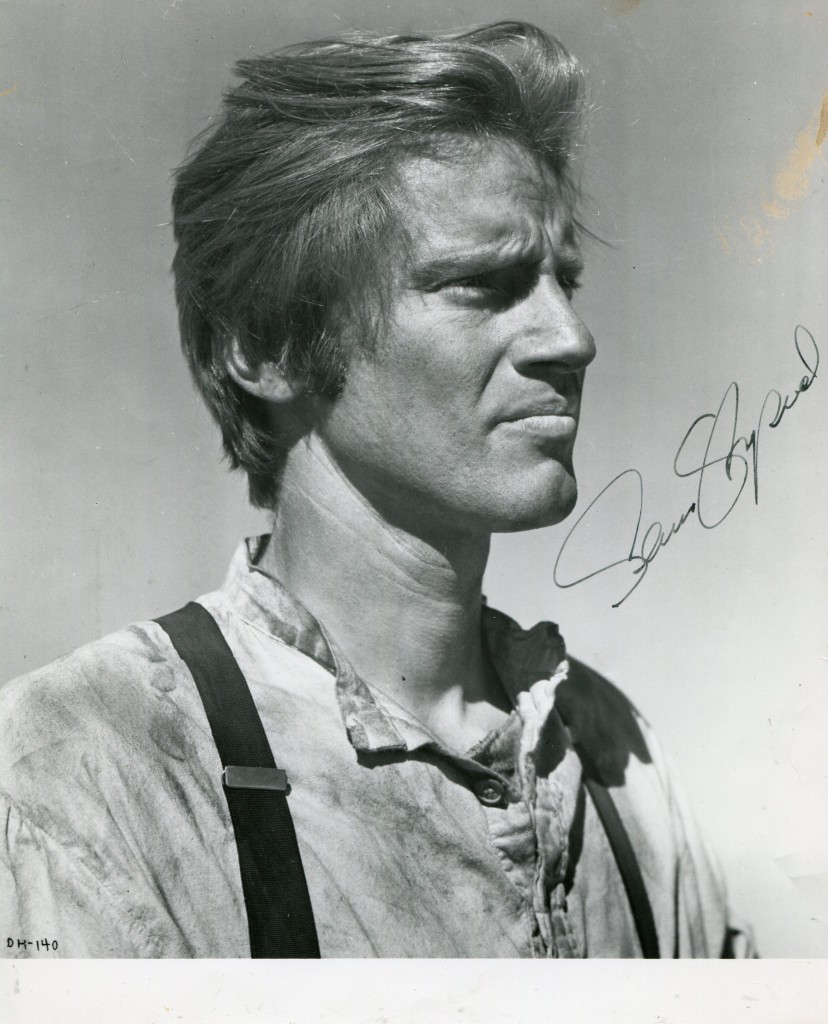

Obituary: Sam Shepard

Playwright, actor, writer, drummer and haunter of Dublin late at night

2017.

Jimmy Fay, who directed Shepard’s plays True West twice (once for the Lyric in Belfast, and once for the Abbey), Ages of the Moon and Curse of the Starving Class, also in the Abbey in 2011, described him as “generous, razor sharp, experimental, strange, iconic, Elvis-like”, while also being “utterly engaging, interested in people, an outdoors man, a great poet who always had to write”.

He could fuse Samuel Beckett and Little Richard. He could combine pop rock with existentialist angst. He was able to make really odd, strange, beautiful plays. He gave a voice to the drama of the heartland. He was a horseman, who raised thoroughbreds, and loved jazz and read Proust. He was gloriously paradoxical.

“He was an extraordinary artist with a brain bigger than anyone else around him,” Fay said. “And I was in awe of him.”

Born Samuel Shepard Rogers VII in Fort Sheridan, Illinois on November 5, 1943, the eldest of three children, his early years were nomadic. His father was a bomber pilot in World War II, so the family moved from one military base to another, taking in South Dakota, Guam and Florida before settling in an avocado ranch in Duarte, California.

His father’s experiences of war deeply affected him and he became an alcoholic, which later inspired Shepard’s finest semi-autobiographical plays featuring dysfunctionality and darkness.

After abandoning an agricultural degree, he arrived in New York in 1963, a counter-cultural cauldron with “a cowboy mouth with matinee-idol looks”, a mid-western drawl and vague aspirations to act, make music and write. After securing a job as a busboy at the Village Gate nightclub, he became part of the underground avant-garde movement.

His first Gestalt pieces, Cowboy and The Rock Garden, caused confusion and some uproar when they were first shown Off Off Broadway. New York, it seemed, wasn’t ready for such a raw injection of profane language and psychodrama.

He won OBIEs (Off-Broadway Theater Awards) for Chicago, Icarus Mother and Red Cross. In 1967, he wrote his first full length play, La Turista, an allegory on the Vietnam war about an American couple in Mexico and won his fourth OBIE. He won 13 in total.

His early science-fiction play, The Unseen Hand (1969), influenced Richard O’Brien’s The Rocky Horror Show, while Operation Sidewinder featured a computerised snake, hopi Indians, black panthers, and his rock group, the Holy Modal Rounders, for which he played drums.

John Lahr, a former theatre critic at The Nation and the Village Voice, described it in The New Yorker. “He didn’t conform to the manners of the day; he’d lived a life outside the classroom and conventional book-learning. He was rogue energy with rock riffs. In his coded stories of family abuse and addiction, he brought to the stage a different idiom and a druggy, surreal lens,” Lahr wrote.

In 1979 he won a Pulitzer Prize for his play Buried Child, which was part of a quintet of family tragedies including Curse of the Starving Glass, (1977), and True West (1980), which depicted the rivalry between two estranged brothers, later to be played by actors including Philip Seymour Hoffman, Gary Sinese and John Malkovich. Fool For Love (1983) and A Lie of the Mind, (1985) established him as one of the visionaries of US theatre. By the age of 40, he had become the second most widely performed US playwright after Tennessee Williams.

When Curse of the Starving Class was performed in The Abbey theatre, in 2011, Shepard became the Abbey’s most frequently staged playwright. Joe Hanley, who played the role of the explosive alcoholic father Weston in the semi-autobiographical play, said of Shepard: “He was the last of the great American writers. A theatrical and gifted man without ego.”

At the time his playwriting was beginning to peak, with predictable oddity he became a romantic movie lead in movies such as Baby Boom. “The shift was so unexpected that many of his fans in the theatre thought it had to be somebody else when his name appeared with Richard Gere and Brooke Adams in Days of Heaven, but his on-screen magnetism was powerful enough to match, if not overpower Gere’s own,” film critic Gene Seymour said.

In 1983, Shepard was nominated for an academy award for Best Supporting Actor as his portrayal of pilot Chuck Yeager in The Right Stuff. He also starred in Steel Magnolias, Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven, Frances with his partner-to-be Jessica Lange, The Notebook, Black Hawk Down, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford and The Pelican Brief, with Julia Roberts amongst others. Recently, he starred as in Bloodline on Netflix.

Despite his many acting credentials, Shepard humbly insisted that his performances were ‘hit and miss’.

In February of this year, his book, The One Inside – a collection of short stories – was hailed by actor Ed Harris. “The most intimate thing he wrote. Read that and it’s like you’re holding the essence of Sam in your hands,” he said in an obituary in the Guardian. “Exploring his characters is like a bottomless pit. We just did 125 performances of Buried Child in London and we’re still discovering things about these people at the end of the run.”

Shepard was constantly working on something. Once one thing finished, he would move onto the next, be it a poem or a screenplay, but he also had a great impulse to hit the open road, as his ex-lover Patti Smith wrote in her evocative piece: “Sam liked being on the move. He’d throw a fishing rod or an old acoustic guitar in the back seat of his truck, maybe take a dog, but for sure a notebook, and a pen, and a pile of books.”

Unlike modern stars, who court attention, Shepard was very private. He didn’t like flying or the internet, used a typewriter and liked to roam the streets freely.

He married actress O-Lan Jones with whom he had a son, Jesse Mojo Shepard, in 1969. He met Jessica Lange while making the movie Frances in 1982. They were together for almost 30 years until 2009. They had two children, Hannah Jane and Samuel Walker. All three of his children were with him when he passed away.

He was cowboy, a badass and an enigma, who, according to Lange, wasn’t easy going. “But no man I’ve ever met compares to Sam in terms of maleness,” she said. She was probably wrong though.

She probably meant to say that no one ever compares to Sam

IMDB entry:

As the eldest son of a US Army officer (and WWII bomber pilot), Sam Shepard spent his early childhood moving from base to base around the US until finally settling in Duarte, California. While at high school he began acting and writing and worked as a ranch hand in Chino. He graduated high school in 1961 and then spent a year studying agriculture at Mount San Antonio Junior College, intending to become a vet.

In 1962, though, a touring theater company, the Bishop’s Company Repertory Players, visited the town and he joined up and left home to tour with them. He spent nearly two years with the company and eventually settled in New York where he began writing plays, first performing with an obscure off-off-Broadway group but eventually gaining recognition for his writing and winning prestigious OBIE awards (Off-Broadway ) three years running.

He flirted with the world of rock, playing drums for the Holy Modal Rounders, then moved to London in 1971 where he continued writing.

Back in the US by 1974, he became playwright in residence at San Francisco’s Magic Theater and continued to work as an increasingly well respected playwright throughout the 1970s and into the ’80s.

Throughout this time he had been dabbling with Hollywood having, most notably in the early days, worked as one of the writers on _”Zabriski Point” (1970)_, but it was his role as Chuck Yeager in 1983’s The Right Stuff (1983) that brought him fully to the attention of the wider, non-theater audience.

Since then he has continued to write, act and direct, both on screen and in the theater.