Tom Vallance & Gilbert Adair’s “Independent” obituary from 1996:

Paradoxically, it was by assuming and exploiting the ostensibly limited measure of creative freedom afforded by genre movies that Hollywood directors, writers and performers produced their most durable work – more often and more durably, it could be argued, than when scaling the heights of “self- expression” to which a few would eventually graduate. Although scandalously neglected by the Academy Awards, the musical was one of the American cinema’s most glorious indigenous genres, and one which was to offer those who worked within it licence of a kind that was denied them in their “straight” movies: licence in the stylisation of decor and costume, of course, but also in the elaboration of camera movement and the exploration of filmic space.

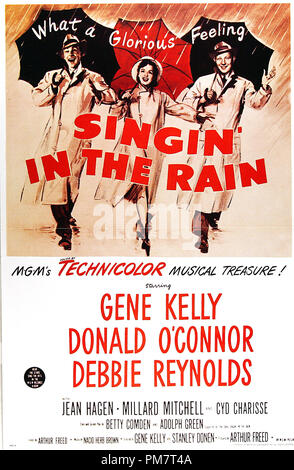

Most notably in his collaborations with Stanley Donen, Kelly opened up, “aerated”, the performing space of the Hollywood musical of the early Fifties, whose fundamentally theatrical origins still tended to show through, and created for the cinema what might be termed an “impossible stage”, whose spatial parameters would be ceaselessly redefined before our dazzled and discombobulated eyes. With Donen he co-directed a trio of musicals of paramount importance and almost infinite charm, one of which, Singin’ in the Rain (1952), is widely regarded as the finest of all.

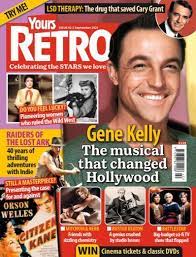

To most moviegoers, however, Gene Kelly was familiar only as a performer, as a face, as a great, grinning, apparently indelible smile – one that recalled both the devil-may-care nonchalance of a Douglas Fairbanks (it was not by chance that in 1948 Kelly played d’Artagnan in one of the umpteen screen adaptations of The Three Musketeers) and the unquenchably breezy optimism of a Harold Lloyd – a smile around which his trim, athletic figure would indefatigably circle and spin. The most peerlessly debonair dancer of the 1930s (and, indeed, of the entire history of the cinema) was Fred Astaire. But if Astaire made one think of an angel momentarily come to rest on earth, then Kelly was a dancer who, in a wholly unpejorative sense, had his two feet firmly on the ground.

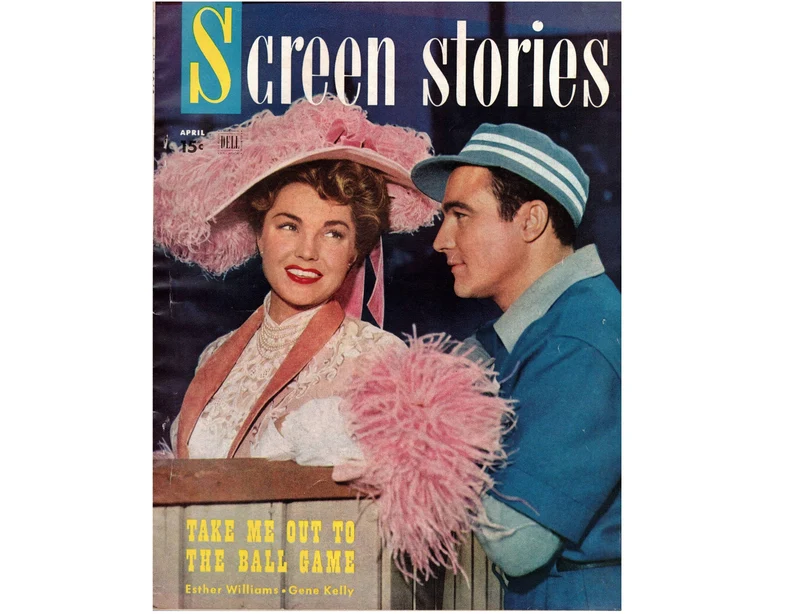

From out of the bijou white-walled penthouse suites in which Astaire and Rogers would rotate like figurines on a music box Kelly took dancing down into streets and squares and parks; and to the silken white-tie strait- jackets that set his predecessor off to such dashing advantage he preferred, in movies like Anchors Aweigh (1945) and On the Town (1949), the more robust and homely white of a sailor’s bell-bottoms, investing them with the fantastical charm of those decorative races, clowns, Pierrots and Harlequins. The choreographic language that Kelly introduced into the American musical carried the very first hint of the vernacular, of slang.

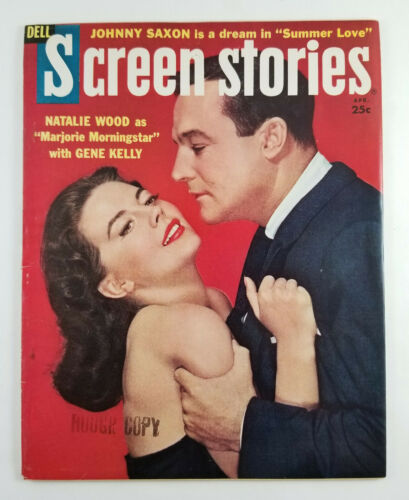

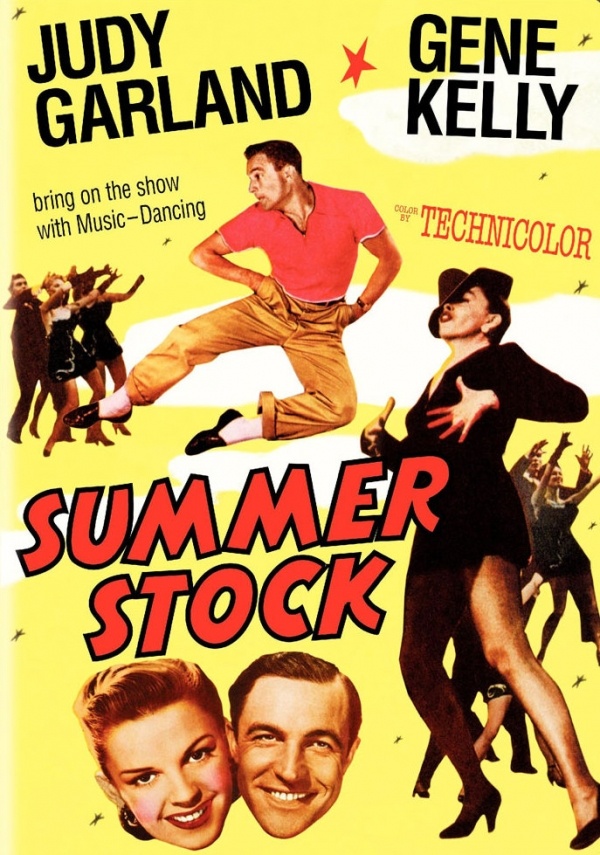

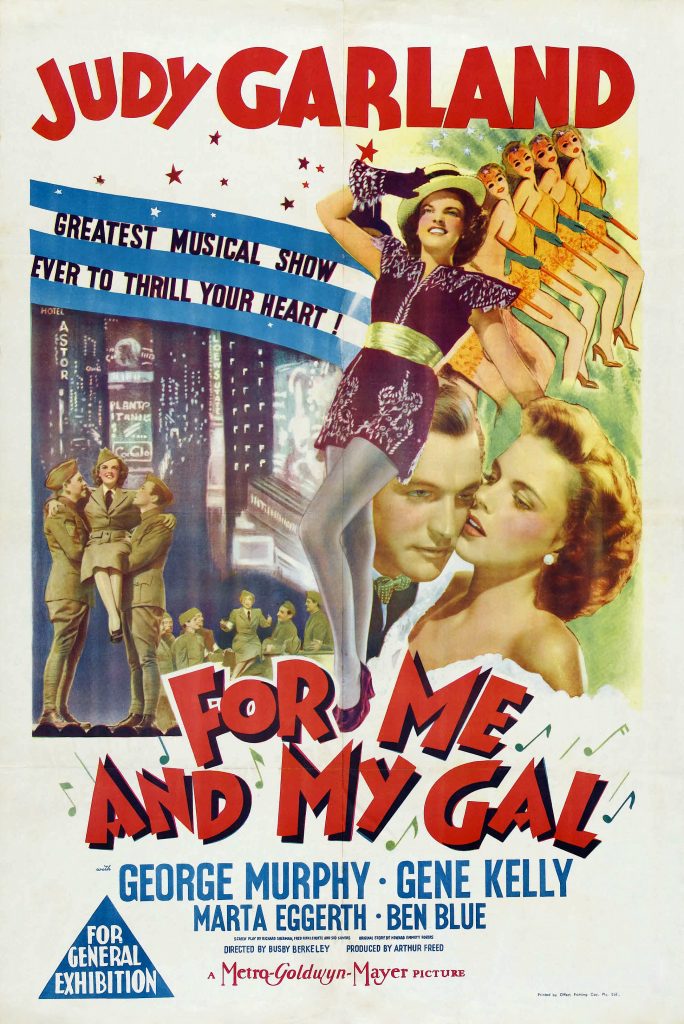

Kelly had been a dancer – or “hoofer”, a term that might have been coined for him – since his childhood. He became a professional in 1938 as a male chorine in the Broadway musical Leave It to Me and in 1940, one of several anni mirabiles in his career, he choreographed “Billy Rose’s Diamond Horseshoe” and was cast in the title role of Pal Joey, Rodgers and Hart’s groundbreaking musical version of John O’Hara’s short story. Then, only one year later, he was offered the male lead opposite Judy Garland in Busby Berkeley’s For Me and My Gal, the first of his appearances in a long series of MGM musicals, which later included four by Vincente Minnelli: Ziegfeld Follies (1946), a portmanteau homage to one of the most flamboyant of Broadway’s showmen, in which he would perform a droll, self-debunking song-and-dance routine, “The Babbitt and the Bromide”, with Fred Astaire; The Pirate (1948), in which his neo- Fairbanksian panache was ideally suited to the role of a ham actor mistaken for a buccaneer; most memorably, perhaps, An American in Paris (1951), which concluded with his celebrated “Ecole de Paris” ballet; and, finally, Brigadoon (1954, with Cyd Charisse and Van Johnson).

It was also in 1949 that Kelly was teamed with Stanley Donen to direct On the Town, usually credited as the first modern film musical. In fact, much of it was in a traditionalist MGM mould, and only its opening sequence could claim to be genuinely innovatory. Filmed completely and (for the period) adventurously on location, it presented Kelly, Frank Sinatra and Jules Munshin (the one whom everyone tends to forget) as three sailors released at dawn from the Brooklyn Navy Yard on a 24-hour pass and gawpingly absorbing the sights and sounds of the big city. The remainder of the film, though far more dance- oriented than most previous musicals, was conventionally studio-bound.

But, as Kelly himself said, “The fact that make-believe sailors got off a real ship in a real dockyard and danced through a real New York was a turning-point in itself.”

On the Town was followed by Singin’ in the Rain, which wears its unrivalled and by now ultra-familiar perfection as lightly as ever. And that in turn by It’s Always Fair Weather (1955), a bizarrely sour and disillusioned musical filmed not merely in but for CinemaScope, its dance numbers so inventively filling out the pillar-box format that the film is virtually impossible to screen on television.

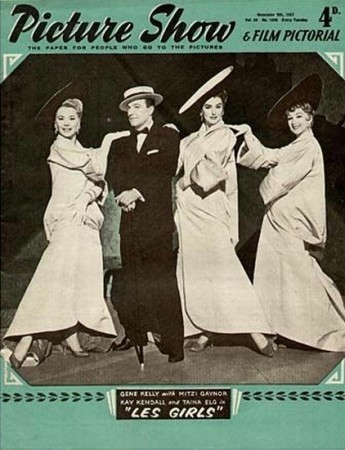

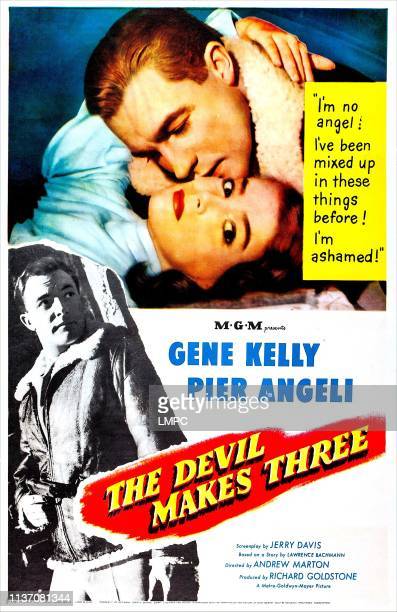

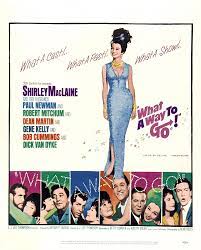

Unaided, Kelly directed two subsequent musicals: Invitation to the Dance (1956), an uneasily self-conscious three-part essay in pure ballet, whose most amusing episode found him dancing with “Tom” of Tom and Jerry, and, for 20th Century-Fox, Hello, Dolly! (1969, with Barbra Streisand and Walter Matthau), a totally misguided endeavour to recapture the euphoric buoyancy of his earlier work but whose top-heavy imagery reminded one of nothing so much as the elephants’ lumbering slow-motion cancan in Saint-Saens’s The Carnival of the Animals. His non-musical work as a director (i.e. The Happy Road, 1957, Tunnel of Love, 1958, Gigot, 1962, A Guide for the Married Man, 1967) was utterly unmemorable; that as actor (Christmas Holiday, 1944, Black Hand, 1950, Inherit the Wind, 1960), a little less so.

But none of his failures will ever efface the memory of the modest production number that gave his masterpiece, Singin’ in the Rain, its title; and one has only to hear its introductory bars – tum-te-tum-tum tum-te-tum- te-tum-tum – to see him again, in a dance as negligent and somehow as instinctive as a shrug of the shoulders, effortlessly sashay down that rain-streaked street on the MGM back lot. No one but Gene Kelly could have made rain seem so very sunny.

Gilbert Adair

Singin’ in the Rain came at the very peak of Gene Kelly’s career and was the last of his masterpieces, so how fitting that it should include his best-loved routine – filmed in just a day and a half, so thorough was his preparation, writes Tom Vallance.

Kelly’s role in the film as Don Lockwood, a swashbuckling star of the silent cinema, is reminiscent of the character he parodied so hilariously with Judy Garland in The Pirate, while the title number’s street setting is a reminder of earlier triumphs – the “Alter Ego” dance in Cover Girl, the joyous opening gambol through the streets of New York in On the Town and the celebration of love and youth, “Wonderful”, on the Parisian boulevard of An American in Paris. The street in Singin’ in the Rain is in California where his sweetheart warns him that the “dew is just a little heavier than usual tonight”, but Kelly doesn’t care. He and his friends have discovered a way to turn the silent action star into a song-and-dance man for the talkies. He is on the brink of a new career and he is in love and what follows is a joyous celebration of these facts.

“Moses Supposes” in the same film may be a finer display of pure tap, but the title number is uniquely Kelly’s, a summation of his style which not only features child-like splashing through puddles – that element of the eternal child in us all and a reminder of Kelly’s earlier brilliant work with children – but even includes the line “Come on with the rain, I’ve a smile on my face,” so appropriate for a star whose broad Irish grin was such an indelible part of his charm.

Taking no heed of his girl’s warning (“Where I’m standing the sun is shining”), he waves away his taxi and and as he strolls off begins to hum the counter-melody before launching into full song, his euphoria mounting as he leaps on to a lamppost and embraces it, gaily waving to a couple who hurry by with a newspaper over their heads. Arms outstretched, he beams as the camera swiftly tracks in for the famous grinning close-up, then he strolls, insouciantly twirling his umbrella, before starting a second chorus with “Dancin’ in the rain . . .”, the sound of his taps on the wet pavement having a beguiling sonority.

Throughout the number Kelly uses his umbrella as a prop, twirling or kicking it, juggling with it, using it as a banjo or a partner, running it along railings and, as he does a jaunty sideways step to the left, twirling it to the right above his head. Standing under a pouring drain- pipe, he abandons its protection completely before joyously whirling full- circle in the street as the orchestra’s brass sweeps into the main melody before strings take over as Kelly delicately trips on and off the sidewalk as if on a tightrope (the magnificent orchestration was the work of MGM’s ace arranger Conrad Salinger). Finally, Kelly splashes with gay abandon through the puddles before the reproving gaze of the law curtails this transport of delight and, giving his umbrella to a passer-by, he disappears happily into the night.

Eugene Curran Kelly, actor, dancer, director: born Pittsburgh 23 August 1912; married 1941 Betsy Blair (one daughter; marriage dissolved 1957), 1960 Jeanne Coyne (died 1973; one son, one daughter); died Los Angeles 1 February 1996.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.