Shelley Winter’s obituary by Veronica Horwell from 2006 in “The Guardian”:

Two blondes paid the rent at 8573 Holloway Drive, Los Angeles, a block south of Sunset Boulevard, in 1951. Both were starlets on studio contracts, and they commiserated with each other over the bones in basque bodices, diets and other career impositions. On Saturday mornings, they played classical records and read the accompanying booklets about composers, and once they sat down to list the famous men they dreamed of fucking.

The younger, Marilyn Monroe, listed Albert Einstein and Arthur Miller among her hunks. The wiser woman, Shelley Winters, who has died of heart failure aged 83, stuck to movie studs. She lived to make most of them, and hang out with a couple of Oscars as well.

She was born Shirley Schrift in St Louis, officially in 1922 (though some sources still say 1920) and the family soon moved to Brooklyn. Her father was jailed for arson – and later cleared – when she was nine. On Wednesdays, she would slip into the Broadway theatres to catch the matinees, and as a teenager she competed with half of America for the part of Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With The Wind. Director George Cukor bought her a Coke and asked her about her acting ambitions, which were serious.

She worked in Woolworth’s – “I wasn’t pretty enough for the candy department so they put me to work selling hardware” – where she led the other girls in a strike for unrestricted access to toilets. They won, but Woollies would not re-employ her. “I’d have made a damn good union organiser,” she said years later. “Look at the facts. There are no more padlocks on the loos in Woolworth’s.”

She went to acting school, took the advice of her opera singer mother, Rose, and stumped round the borscht circuit; she was appearing in the musical Rosalinda on Broadway in the early 1940s when the president of Colombia Pictures, Harry Cohn, went backstage and said, “Listen kid, you think you could do the same thing in front of a camera?”

Her first screen appearance was in What a Woman! (1943). But it took “Shelley” (from her favourite poet) “Winters” (her mother’s maiden name plus a publicist’s “s”) seven years to “climb out of the studio wastebasket”. She did it by way of lowclass victimhood – as a waitress strangled by Ronald Colman in George Cukor’s A Double Life (1947), a gas station Myrtle run over by Gatsby’s car in The Great Gatsby (1949) and a factory girl drowned by the man who got her pregnant in A Place in the Sun (1951), her first Oscar nomination.

Her southern widow, in The Night of the Hunter (1955), was about as far as Winters could develop that persona: “she has a rich body” is the character’s introduction in the screenplay, although she ends up as a dead body, her hair drifting in the river. As Ian Cameron once wrote, Winters too easily played the female equivalent of Peter Lorre, her quivering pathos inviting martyrdom.

While playing an extra in The Big Knife (1955), she said, “Those lousy studios, they louse you up and then they call you lousy.” She seemed to be describing her relative movie non-progress: she had displayed the clavicles and the lips just fine, but her attitude was too visible.

With her press agent, she began to make herself over into “this personality, a dumb blonde with a body and a set of sayings”. She scripted her own wisecracks (“I did a film in England in the winter and it was so cold I almost got married”). Dylan Thomas had sent her letters, and she had sent him to a shrink who failed to cure the drink; on a visit, she “asked why he’d come to Hollywood, and, very solemnly, he said to touch a starlet’s tits. Ok, I said, but only one finger.” Her other literary buddy, Tennessee Williams, didn’t even peek.

But Winters was also a pro, who studied with Lee Strasberg at the Actors’ Studio, working towards the “ability to reveal myself, the willingness … you act with your scars … if you want the best, you have to fight for it”. In the year of The Night of the Hunter, she left for the Broadway stage, and did not return to cinema until 1959, when she came back a changed woman – her truer self.

“Overeaters anonymous, it’s my only religion,” she said of her expanded flesh. This emphasised her kept-woman-of-the-Hapsburg-empire appearance, although the calorie intake was all-American, her favourite meal being tuna on rye with a chocolate milk shake.

She won an Oscar for her first substantial role in this mother-matron-madam mode for The Diary of Ann Frank (1959), and made the embonpoint and dirty laugh work for her through the 1960s: a slut of a mum in Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita (1963); the racist mom in A Patch of Blue (1965, another best-supporting Academy award); the bordello boss Polly Adler in A House is not a Home (1964) – a variation on her whore-for-intellectuals in The Balcony (1963); a Tommy-gun-wielding Bloody Mama (1970); and a passenger in The Poseidon Adventure (1972). Only a few films utilised her ability to distance herself funnily – pulling the alarmed Alfie (1966), or unafraid of falling among Indians in The Scalphunters (1968) because “they’re only men”.

For all her lack of the camera-ready face of her friend Liz Taylor, Winters was desired. Maybe it was that rich body. Her under-age affair with a fellow thespian ended in pregnancy, an abortion and her refusal of a marriage offer because “you’re a bit-part actor and I’m a potential star”. There were three brief marriages: the first, in wartime, was to Paul Mayer, a US army air force captain; the others were to an Italian actor, Vittorio Gassman (with whom she had a daughter) from 1952 to 1954, and an Italian-American actor, Anthony Franciosa, from 1957 to 1960.

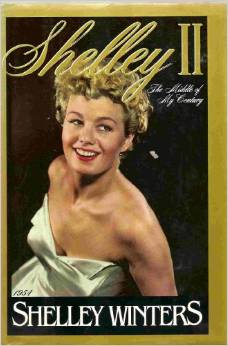

Winters published two volumes of autobiography, Shelley, Also Known as Shirley (1980) and Shelley II: The Middle of My Century (1989). In those brash works, she consumed much of the beefcake on that 1951 wish list. “The only way to keep warm in this apartment is to get into bed. My body generates a great deal of heat,” mumbled Marlon Brando. “Fuck me please and send a copy of your speech later,” she demanded of a prosy Burt Lancaster. She ended up in bed five times with William Holden after Christmas studio parties.

Winters thought masculine star attempts at style hilarious, and would say so, with her mink eased off the shoulder and a glass of fizz in hand. She once described how, during a private movie showing at Errol Flynn’s house, a bed slipped into the room, complete with small bar, icebox and the top sheet turned back, as the ceiling mirror rolled away to to reveal the heavens through a magnolia tree in flower. She was more a faux-leopard-skin couch gal herself.

In all, there were 150-odd films (“Have you seen them all, honey?” she inquired of a gushy interviewer), including an artistic production shot in Italy but never released as they lost the soundtrack, and a wicked scene in A Portrait of a Lady (1996), where she nearly upstaged John Gielgud on his “death-bed”. She was a success on Broadway in Minnie’s Boys (1970), playing the mother of the Marx Brothers, had variable reviews for her off-Broadway playwriting debut, One Night Stands of a Noisy Passenger (1970), and recurred as TV sitcom Roseanne Barr’s grandmother in kaftan and watch cap. Roseanne did look and sound as if she had inherited granmaw’s motormouth.

Towards the end, Winters lunched with her camp court almost daily in Los Angeles’s Silver Spoon Schwabs, complaining about the hernias those basques had caused and recalling Marilyn fondly. She transported a visiting journalist around town in her limo – “See,” she said, pointing to her gold star in the pavement, “I’m there with all the communists.”

“I could face respectability over 60,” she confided, secure among multiple chins, fur coats and Impressionist paintings: ” I think on-stage nudity is disgusting, shameful … But if I were 22 with a great body, it would be artistic, tasteful, patriotic and a progressive religious experience.” She is survived by Jerry DeFord, her companion since the early 1980s and her daughter.

· Shelley Winters (Shirley Schrift), actor, born August 18 1922; died January 14 2006

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.