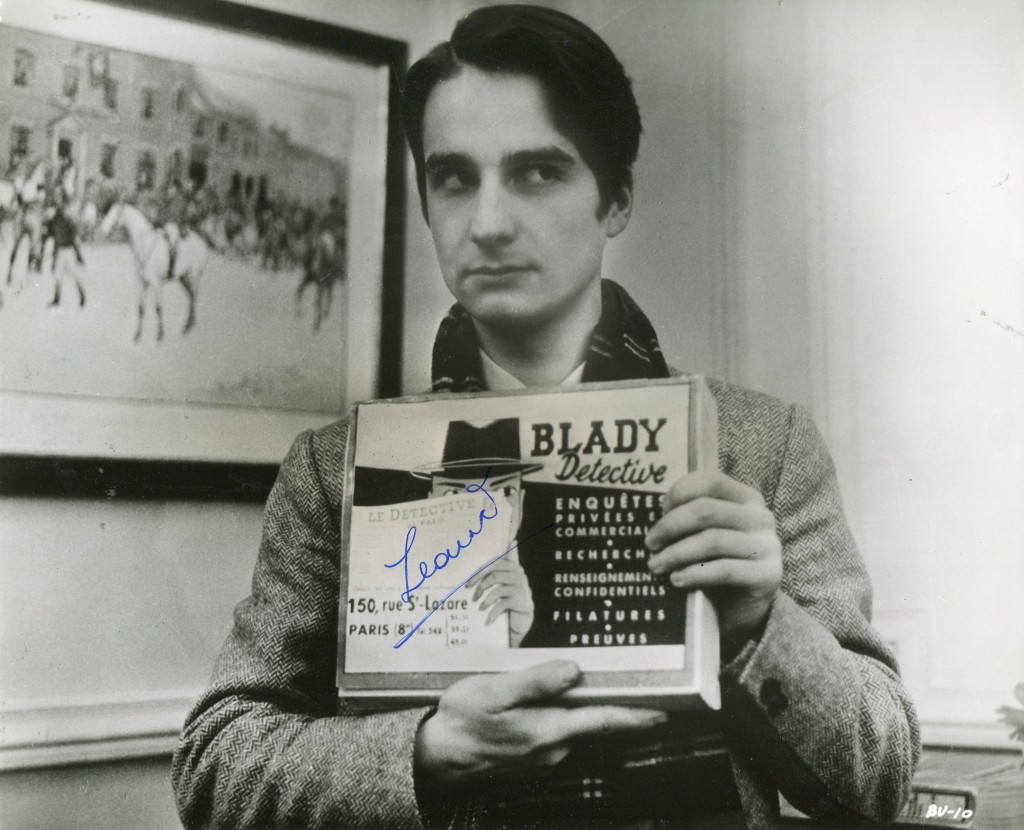

Jean-Pierre Leaud was born in 1944 in Paris. He first came to fame as a boy actor in 1959 in “The 400 Blows” in 1959 which was directed by Francois Truffaut. He became associated with the films of Truffaut including “Bed and Board” in 1970 and “Two English Girls” and especially in 1973, “Day For Night”. He also made many films with Jean-Luc Goddard.

TCM overview:

n his first major film role as Antoine Doinel, Jean-Pierre Leaud exhibited a mature command as an unloved youth who turns petty thief in Francois Truffaut’s memorable classic “The Four Hundred Blows” (1959). The film’s final frozen image of Leaud’s round face staring at the camera with a mixture of humor and confusion has become a familiar screen image. Truffaut went on to direct the actor in six additional films, four of which detailed the further adventures of Doinel. Leaud matured into a lanky, sharp-featured but furtive man. Over the course of the series, he proved to be a modest talent with his initial performance the best. As Leaud matured along with the character of Doinel, he demonstrated his limitations, playing against the sentimentality of “Stolen Kisses” (1968) and lending an almost cold presence to “Bed and Board” (1970, easily the weakest of the entries in the series). The final installment, “Love on the Run” (1979), was a modest effort. Despite having allied himself with Truffaut (Leaud also gave adequate performances in 1971’s “Two English Girls” and 1973’s “Day For Night”), the actor also forged working relationships with several of the key figures of the New Wave, most notably Jean-Luc Godard. “Masculin-Feminin” (1966) offered Leaud a role not dissimilar for Doinel, a hopeless romantic searching for true love. He received some notice as the callow central figure in a love triangle in “La Maman et la putain/The Mother and the Whore” (1973). But after Truffaut’s untimely death, Leaud seemingly lost interest while continuing to work. Reportedly dealing with personal problems, he became a much more haunted screen presence, often cast as filmmakers (e.g., Godard’s “The Rise and Fall of a Small Film Company” 1986; Olivier Assayas’ “Irma Vep” 1996) or neurotics (i.e., the father in “Paris at Dawn” 1991). The eternal question posed at the end of “The Four Hundred Blows” seems as appropriate in the 90s as it did in 1959: what was to become of this person? It is one only time could answer.