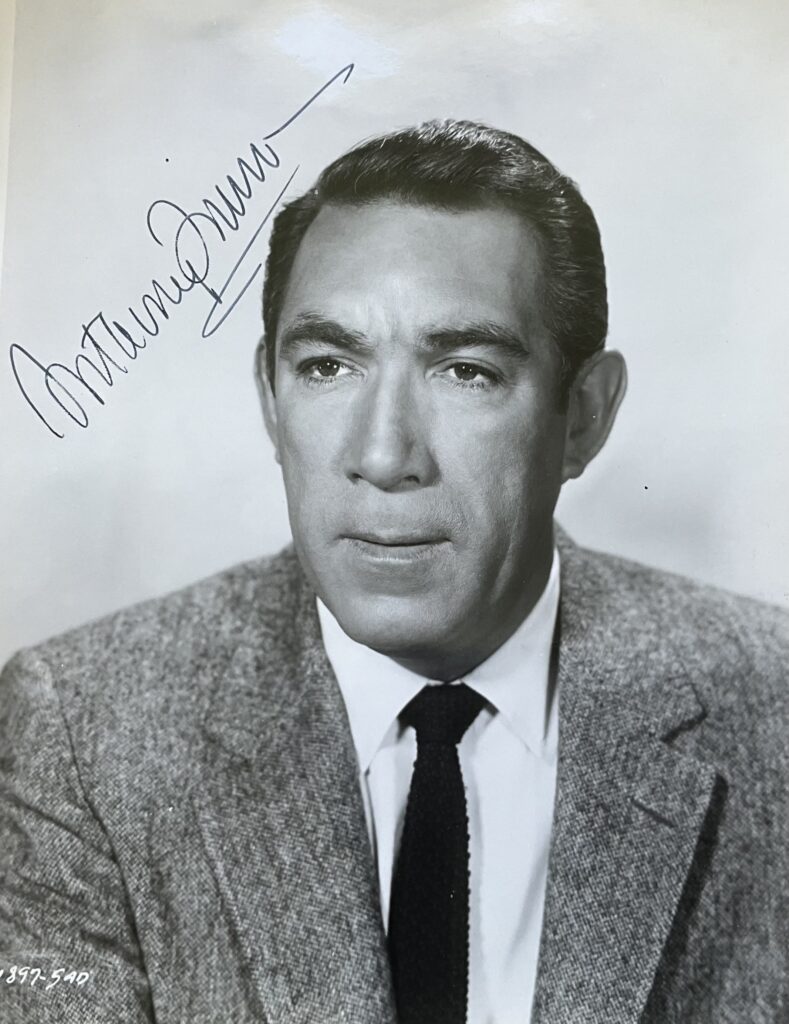

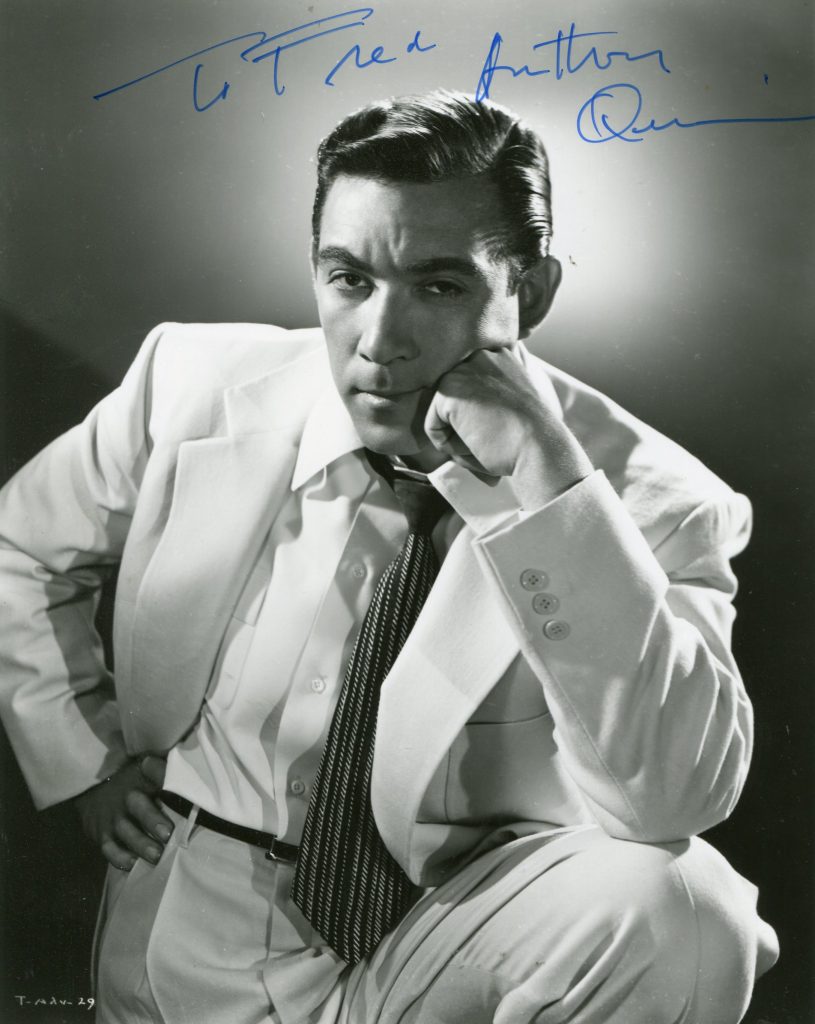

I met Anthony Quinn once in London in 1994. A friendly man, he talked a little about “The Guns of Naverone”. Quinn is one of my favourite actors. He had a very long movie career. He was born in 1915 in Mexico.His grand father was from Cork.. He began making films in 1936 in “The Milky Way”. He had support parts throughout the 1940’s in such films as “The Black Swan” in 1952. He won two Oscars in the 1950’s and then became a major movie star in the 1960’s in such films as “Laurence of Arabia” in 1962 and “Zorba the Greek” in 1964. In 1990 he starred with Maureen O’Hara and John Candy in “Only the Lonely”. He died in 2001 at the age of 86.

His obituary from “The Guardian” by Ronald Bergan:

There has always been a resistance among some inhibited Anglo-Saxons to the rumbustious personality of Anthony Quinn, who has died aged 86.

Some, however, like Basil (Alan Bates), the buttoned-up English writer in Zorba The Greek (1964), gradually became intoxicated by his life-force character. In fact, there were few better noble savages in Hollywood movies.

When he emerged as a leading performer in the 1950s, constantly roaring for our attention and sympathy, following more than 10 years as an all-purpose, ethnic supporting actor, Quinn was the antithesis of introspective stars like Montgomery Clift, Marlon Brando and James Dean, and reserved English ones such as Rex Harrison and David Niven.

Despite having lived in the United States since childhood, the Mexican-born actor hardly ever played an American, except a native one. His most famous portrayals were as Greeks, Mexicans, Frenchmen, Italians, Arabs and even an Inuk.

He was born in Chihuahua, of poor Irish-Mexican parentage. His maternal grandmother was a Cherokee; his father, who spoke Spanish with an Irish accent, fought with Pancho Villa.

When Anthony was a boy, the family arrived in California as migrant workers picking grapes. After his father died, he did a lot of odd jobs, including shining shoes, boxing professionally at 16, having lied about his age, and preaching for the evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson in the Mexican neighbourhoods of Los Angeles.

He taught himself literature, music and painting, and decided to become an architect after meeting Frank Lloyd Wright.

But the taste for acting diverted him. After studying with Michael Chekhov, and performing with small theatre groups, he was given the wordless role of a prisoner knifed to death in a gangster picture called Parole! (1936). As Paramount wanted actors who could pass as native Americans, Quinn pretended to be a pure Cheyenne to get a role as a chief in Cecil B DeMille’s The Plainsman (1936) starring Gary Cooper.

The same year, he married DeMille’s adopted daughter Katherine, although his father-in-law did little to advance his career, not only to counteract any suggestion of nepotism, but because he did not think much of his acting talent.

Quinn’s parts consisted mainly of foreign heavies or native Americans in a number of Paramount movies, dying in almost all of them. “I was the bad guy’s bad guy,” he said. “I rarely made it to the final reel without being dispatched by a gun or a knife or a length of twine, typically administered by a rival hood.”

Even in DeMille’s Union Pacific (1939), in which he had a small role as a gambler’s hatchet man, he died at the hands of Joel McCrea.

In 1941, when loaned out to other studios, he was given better roles. In Rouben Mamoulian’s Blood And Sand, for 20th Century-Fox, he played a young matador out to win Rita Hayworth from Tyrone Power, and in Raoul Walsh’s They Died With Their Boots On (1941), at Warner Brothers, he was an imposing Chief Crazy Horse. In the same year, his first child, Christopher, drowned in a swimming pool, aged three; he and Katherine went on to have four more children.

Quinn’s first lead was as an illiterate horsebreeder in a small-budget movie called Black Gold (1947), in which Katherine played his wife. However, at the start of America’s anti-communist witchhunt, his leftish leanings made him decide to leave Hollywood and return to the stage. He toured in Born Yesterday, and attended the Actors’ Studio, where he got to know Elia Kazan. Kazan then chose him to replace Marlon Brando, who had gone into films, as Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire, which he played for almost two years on Broadway.

Quinn’s return to the screen was in Robert Rossen’s The Brave Bulls (1951). “The supporting cast was entirely Mexican, and I was thrilled to be in such company,” he commented. “After so many years as the token Latin on the set, I found tremendous security in numbers. For the first time, I belonged.”

This was followed by his Oscar-winning supporting role in Kazan’s Viva Zapata! (1952), in which he played Eufemio Zapata, the hard-drinking, ill-disciplined brother of the hero (Brando).

In 1954, after a few more bandit movies, Quinn made two epics in Italy, Ulysses and Attila, as well as Federico Fellini’s La Strada. In the latter, he was superb as Zampano, the whoring, drunken itinerant strongman who ignores the simple-minded girl (Giulietta Masina) he has put to work as a clown. Cruel as the character is, by the end, Quinn has revealed his own heartbreak and isolation.

Then it was back to the bullring in Budd Boetticher’s The Magnificent Matador (1955), in which, as a great Mexican matador, he took to the hills because “fear is eating him”. Needless to say, he ended up happily slaying bulls once more, encouraged by Maureen O’Hara.

In 1955, Quinn won his second Oscar as supporting actor for his relatively brief, but powerful, performance as Paul Gauguin in Vincente Minnelli’s Lust For Life, sending sparks flying while clashing temperamentally with Kirk Douglas’s Van Gogh.

Because it was felt that no American actress was fiery enough to match Quinn, he was co-starred with the three hottest Italian female stars: Anna Magnani (Wild Is the Wind, 1957), Gina Lollobrigida (The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, 1956) and Sophia Loren (Black Orchid, 1958, and Heller In Pink Tights, 1960).

In 1958, an ailing Cecil B DeMille handed over the direction of The Buccaneer (the remake of his 1938 movie) to his son-in-law. Although Quinn is credited as director, DeMille, who died a month after the opening, cut the film to suit his own tastes, turning it from a more intimate, political drama into a yawning pirate epic.

After two good westerns, Warlock and Last Train From Gun Hill (both 1959), he took on one of his most difficult roles in Nicholas Ray’s anthropological The Savage Innocents (1960), in which he was convincing as an Inuk hunting and fishing in northern Canada, where it was filmed.

Further “savage innocents” embodied by Quinn were the title role in Barabbas (1961) and Mountain Rivera, and the worn-out boxer in Requiem For A Heavyweight (1962). Simultaneously, however, he appeared successfully on Broadway as Henry II, opposite Laurence Olivier in Jean Anouilh’s Becket, and in François Billetdoux’s two-hander, Tchin Tchin, with Margaret Leighton.

After playing a Greek colonel in The Guns Of Navarone (1961), and a Bedouin leader in Lawrence Of Arabia (1962), Quinn applied himself to Michael Cacoyannis’s Zorba The Greek (1964), based on the Nikos Kazantzakis novel. As Alexis Zorba, the passionate, free-spirited Cretan peasant with an earthy laugh and a lust for life, he reached his apotheosis.

According to Quinn, he himself invented the film’s celebrated dance with the sliding step. He had broken his foot the day before shooting began, and found that if he dragged it along, it would not cause too much pain.

“I held out my arms, in a traditional Greek stance, and shuffled along the sands. Soon Alan Bates picked up on the move … We were born-again Greeks, joyously celebrating life. We had no idea what we were doing, but it felt right, and good.”

In 1965, Quinn divorced Katherine and married Iolanda Addolari, the Italian costume designer he had met on the set of Barabbas, four years previously. It was a marriage that lasted 30 years, and produced three sons.

But fidelity was never Quinn’s strong point, and he also had three children by two other women, and affairs with, among others, the French actress Dominique Sanda and Pia Lindstrom, Ingrid Bergman’s daughter.

Although he kept working, he admitted: “The parts dried up as I reached my 60th birthday, loosely coinciding with my growing disinclination to pursue them. Indeed, I could not see the point in playing old men on screen when I rejected the role for myself.”

Quinn then concentrated on painting and sculpture, examples of which sold for thousands of dollars. “Some days, I paint like an Indian. Some days, I paint like a Mexican … I steal from everybody – Picasso, Kandinsky … I steal, but only from the best,” he commented.

In the late 1970s, in two films directed by Moustapha Akkad, The Message, in which he played the prophet Mohammed, and Lion Of The Desert, the story of Omar Mukhtar, the guerrilla leader who fought against Mussolini’s forces in Libya, Quinn became a leading star in the Arab world. “It took the faith of 750m Muslims to restore my faith in myself,” he said later.

Then it was back to being a Greek in The Greek Tycoon (1978), a thinly disguised portrait of Aristotle Onassis, and – at the age of 68 – revisiting his cherished role in Zorba! (1983), the stage musical version on Broadway.

Quinn continued to work in the cinema into the 1990s, notably in Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever (1991), and in A Walk In The Clouds (1995), exhibiting little reduction in his power. His final role was as a mafia boss in Avenging Angelo, with Sylvester Stallone, which is still in production.

In 1996, after an acrimonious divorce from Iolanda, and a heart bypass operation, Quinn, aged 80, had a son and a daughter by his former secretary Kathy Benvin – making him a father 13 times over, by five different women, and continuing, as he always did, to blur the line between his on- and off-screen “earth father” personality.

• Anthony Rudolph Oaxaca Quinn, actor, born April 21 1915; died June 3 2001

The Guardian obituary can also be accessed here.