TCM Overview:

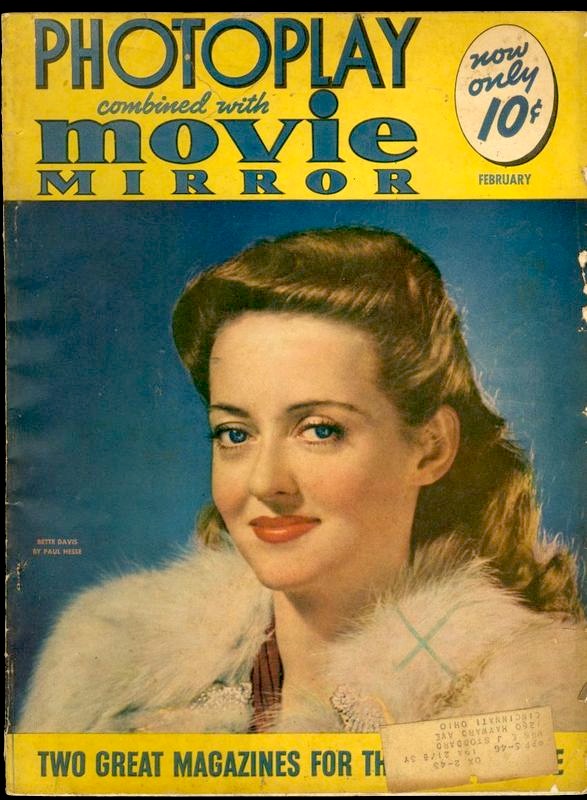

A strong-willed, independent woman with heavy-cast eyes, clipped New England diction, and distinctive mannerisms, Bette Davis left an indelible – and often parodied – mark on cinema history as being one of Hollywood’s most important and decorated actresses. Over the course of her storied career, Davis made some 100 films, for which she received 10 Academy Award nominations, and twice won the Best Actress trophy. But her sometimes over-the-top affectations – which no doubt made her a gay subculture icon – hindered her career despite the enormity of her talents. Not a glamorous star, Davis went through a string of forgettable pictures before tackling the rather unsympathetic Mildred in “Of Human Bondage” (1934), which turned her into a star and earned the actress her first Oscar nomination. She won the Academy Award the following year for “Dangerous” (1935) and later earned her second statue for one of her most famous performances in “Jezebel” (1938). By this time, Davis was a big star and went on to a series of box office hits like “Dark Victory” (1939) and “Now, Voyager” (1942). But after the personal tragedy of losing her husband, Arthur Farnsworth, Davis went into serious professional decline, only to resurrect herself with a delectably over-the-top performance in “All About Eve” (1950). Her resurgence was brief, however, as Davis once again was forced to accept a number of mediocre films while going through a number of personal travails. After emerging one last time with her Oscar-nominated turn in “Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?” (1962), Davis settled into a succession of film and television roles that culminated with her last acclaimed performance in “The Whales of August” (1987). Passing just two years later, Davis was remembered as one of Hollywood’s greatest actresses, a legacy forged by an iron will to go her own way.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

New York Times obituary in 1989:

problems; we are continuing to work to improve these archived versions.

Bette Davis, who won two Academy Awards and cut a swath through Hollywood trailing cigarette smoke and delivering drop-dead barbs, died of breast cancer Friday night at the American Hospital in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France. She was 81 years old and lived in West Hollywood, Calif.

Miss Davis was en route to her home from the San Sebastian Film Festival in Spain, where she had been honored for her acting career. She arrived in Paris on Tuesday and was to fly to Los Angeles, but was taken instead to the hospital, on the outskirts of Paris.

Her lawyer, Harold Schiff, said she had undergone a mastectomy in 1983.

”The doctors had told us the cancer had spread, that it was terminal,” he said. ”The doctors had said let her go on going about her business.” #2 Oscars, 10 Nominations For more than a half century, Bette Davis reigned as a Hollywood star in the grandest meaning of the term. With her huge and expressive eyes, her flamboyant mannerisms and her distinctive speaking style, she left an indelible mark on her audiences in a wide variety of roles.

Nominated for 10 Oscars, Miss Davis was a perfectionist whose tempestuous battles for good scripts and the best production craftsmen for her films wreaked havoc in Hollywood executive suites.

”I was a legendary terror,” she once recalled. ”I was insufferably rude and ill-mannered in the cultivation of my career. I had no time for pleasantries. I said what was on my mind, and it wasn’t always printable. I have been uncompromising, peppery, intractable, monomaniacal, tactless, volatile, and ofttimes disagreeable. I suppose I’m larger than life.”

She was indeed. Few in the entertainment industry could deny that Bette Davis possessed all the legendary indestructibility of the New England Yankee that she was. Starting as a stage actress, she won spectacular fame as a screen star and, as she grew old, shifted effortlessly to high-paying television roles.

Miss Davis’s two Oscars for best performance by an actress were won in 1935, for ”Dangerous,” and in 1938, for ”Jezebel.” But perhaps she is best recalled for her tour de force as Margo Channing, the tough-talking but soft-hearted stage actress in ”All About Eve,” for which she was nominated for an Academy Award.

She made almost 100 films. Her 10 nominations for Oscars are the most any actress has received. And she received many other honors, including the Life Achievement Award of the American Film Institute and the Cesar Award of the French film industry. In 1987 she received the Kennedy Center Honors for lifetime achievements in the performing arts.

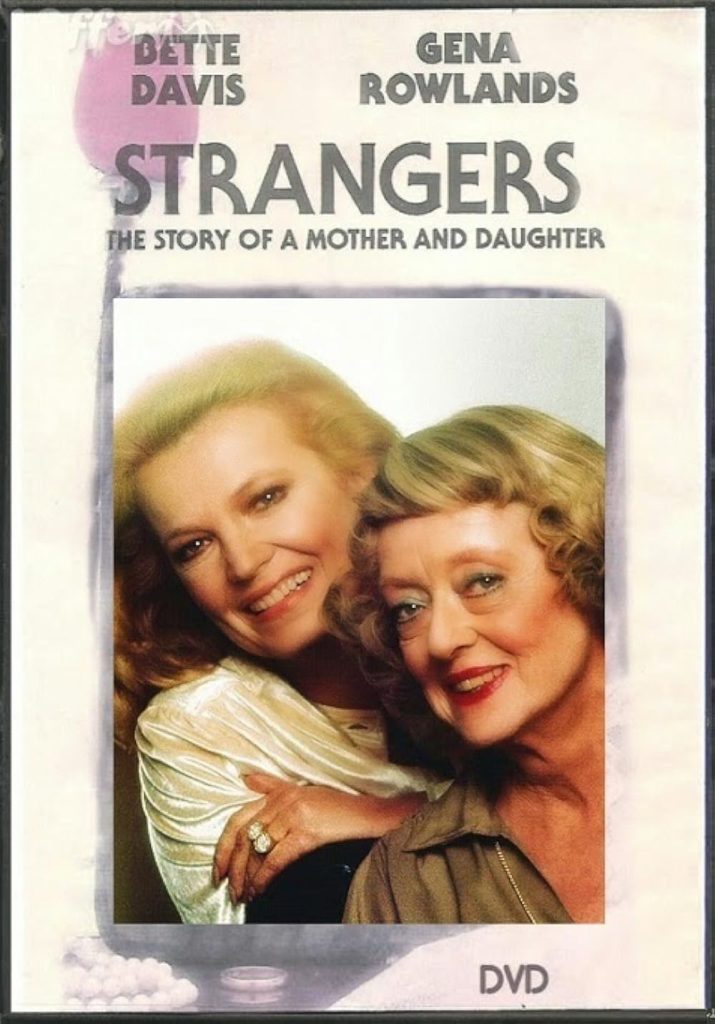

The Kennedy Honors coincided with the release of ”The Whales of August,” a film in which Miss Davis co-starred with Lillian Gish and for which she won wide critical praise. She appeared in that movie and in television and film roles despite having had a mastectomy and a series of strokes while hospitalized in 1983. ”It was my terror that I’d never work again,” she said afterwards, ”for I have always very much loved to work.”

Last April 24, Miss Davis was honored by the Film Society of Lincoln Center at its annual tribute, joining the company of such previous honorees as Sir Laurence Olivier and Charlie Chaplin. ”An honor I’m delighted to get,” she said at the time. ”Greedy, greedy. Can’t have too many awards. I’ve gotten just about every award there is.” Enduring Popularity ‘Acting Should Be Larger Than Life’

Although Miss Davis reached the apex of her popularity in films between the mid-1930’s and the early 50’s, her appeal swept across generations, due largely to her frequent appearances in made-for-television films and the repeated showings of her old, now-classic movies on television.

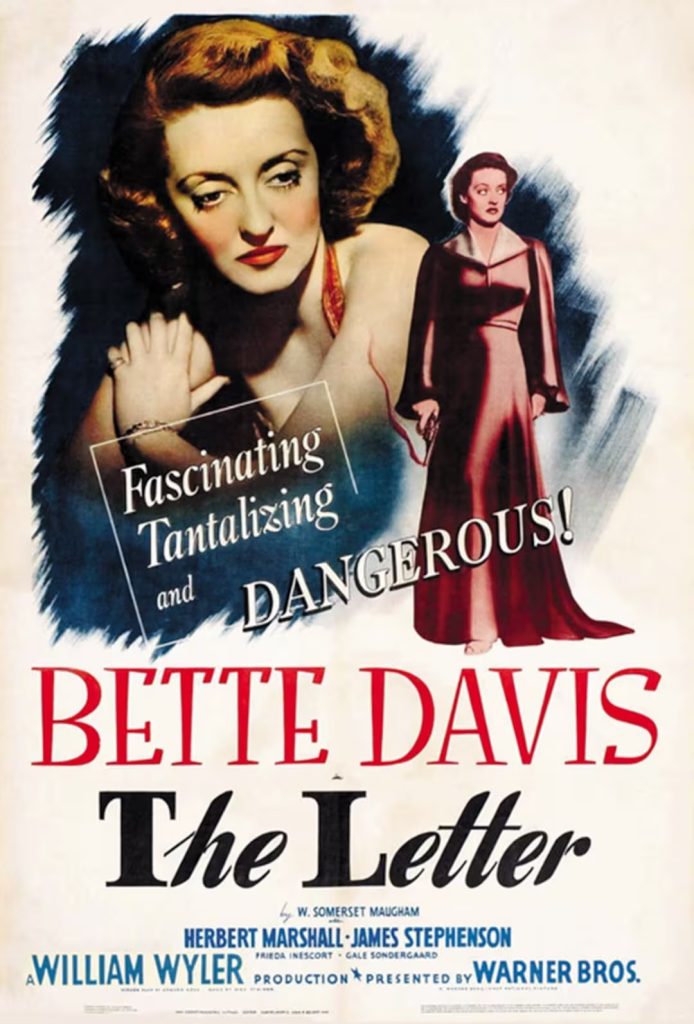

These classics include ”Of Human Bondage,” ”Dark Victory,” ”The Corn Is Green,” ”The Letter,” ”The Great Lie,” ”A Stolen Life,” ”Now, Voyager,” ”Mr. Skeffington,” ”The Little Foxes,” ”The Petrified Forest” and ”Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?”

New generations of entertainers, many of them female impersonators, have found her distinct mannerisms and clipped speech irresistible material for their acts.

”Oh Petah, Petah, Petah,” such an impersonator will say, rolling exaggeratedly widened eyes and puffing savagely on a cigarette. ”What a dump!” And, inevitably, the memorable line that Margo Channing utters as she walks drunkenly up the stairs at her party: ”Fasten your seat belts; it’s going to be a bumpy night.”

”You know, I’ve learned from the imitators,” Miss Davis said in an interview this year. ”I really have. I was never conscious I moved my elbow like that” – she moved it from side to side – ”until I saw someone doing me.”

She was always proud of her approach to acting. ”Natural!” she said. ”That isn’t the point of acting. The public must believe us. They must also be somehow ennobled. Did I ever try to be low-key? Never, never, never! I fought that from the beginning. I think that acting should be larger than life.” At First, Simply ‘Betty’ A Broken Home And School Away

Born Ruth Elizabeth Davis in Lowell, Mass., on April 5, 1908, Miss Davis came from a firmly rooted Yankee background. Her mother was the former Ruth Favor; her father, Harlow Morrell Davis, a Harvard Law School graduate who became a Government patent attorney.

Her father divorced her mother when Miss Davis was 7 and her sister, Barbara, was 5, leaving her mother to rear the children alone. In later years Miss Davis said many times that she saw the divorce as her father’s abandonment of his family, and that it left her barren of love for him and preternaturally devoted to her doting mother.

Mrs. Davis put the girls in boarding school in Massachusetts and moved to New York. In 1917, she was joined by her daughters.

It was at about that time that ”Betty” Davis took the more exotic-sounding name that would become world-famed. A friend of her mother’s who was reading Balzac’s ”La Cousine Bette” suggested the name-spelling change, telling her that it would ”set you apart, my dear.”

In her teens, Miss Davis returned to New England, living in several towns there while her mother worked as a portrait photographer. She waited on tables at her schools, and once, to help with family expenses, posed nude for a woman making a sculpture.

Miss Davis decided in her teens that she wanted to become an actress, and her mother took her to New York in 1928, where she arranged for her to read for Eva Le Gallienne, whose Civic Repertory Theater was then one of the most popular touring companies.

”Miss Le Gallienne thought I was not serious enough in my approach to warrant my attendance at her school,” Miss Davis recalled years later. Breaking Into the Business Stage Experience, Looks and a Voice

Miss Davis’s first professional acting job was with a winter stock company in Rochester, run by the director George Cukor, who dismissed her after a few months. She made her New York acting debut in 1929, at the Provincetown Playhouse in Greenwich Village, in Virgil Geddes’s ”The Earth Between.” Brooks Atkinson, critic for The New York Times, wrote that she was ”an entrancing creature.”

Successes and disappointments were to come in rapid order after that. The young actress, then only 21 years old, was in her first Broadway hit, ”Broken Dishes,” quickly followed by ”Solid South,” in which she played the beguilingly named Alabama Follensby, the first of many Southern-belle roles that were to come her way.

The movies had learned to talk only a few years earlier, and Hollywood was greedily spiriting away Broadway actors and actresses who had good speaking voices as well as looks. It was thus perhaps inevitable that a fresh young actress with some training and experience and a couple of good notices would be asked to take a screen test.

She was given a $300-a-week contract by Universal Pictures, and Miss Davis and her mother went to Los Angeles in 1930. Her first movie role was in ”Bad Sister,” notable only for the fact that it also introduced Humphrey Bogart to films. But the movie’s cinematographer, Karl Freund, passed the word to studio bosses that ”Davis has lovely eyes,” and just as she was to be dropped, her option was picked up for another 13 weeks.

By the end of 1932, Miss Davis, discouraged after having appeared in six lackluster movies and finally without a contract, prepared to return with her mother to New York. Then she got a call from George Arliss, the highly respected English actor, who was to be her mentor until his death.

He hired Miss Davis as his leading lady in ”The Man Who Played God,” her breakthrough movie role.

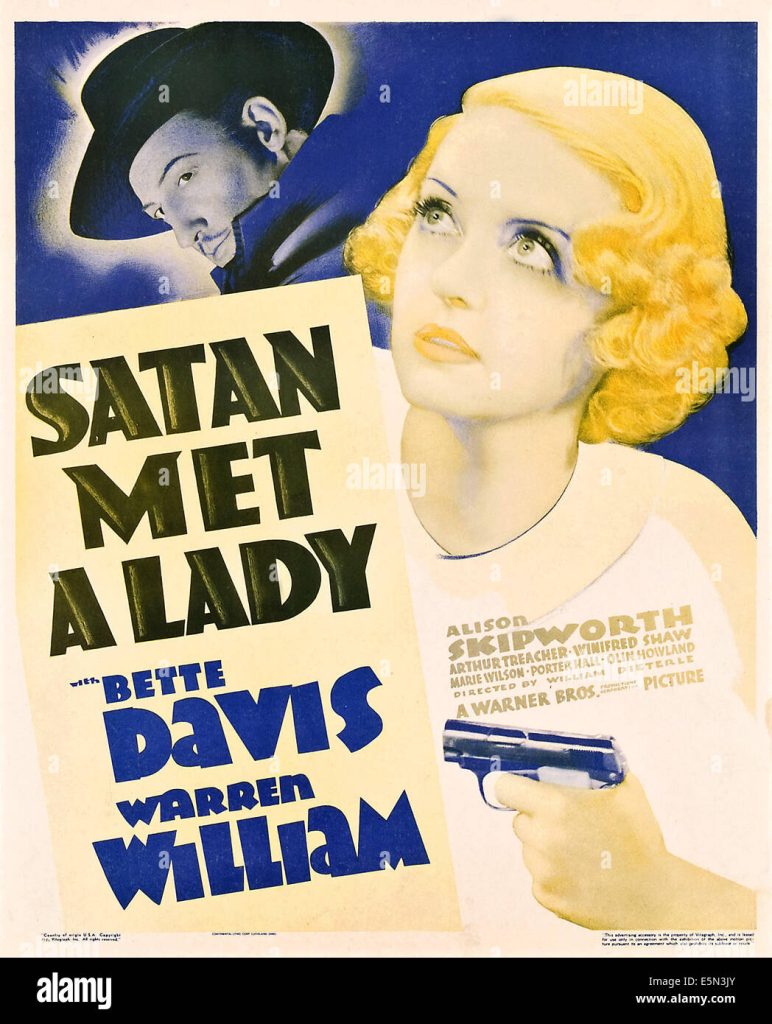

The film was a success, and its producer, Warner Brothers, signed Miss Davis to her first contract. It was the start of a love-hate relationship with the studio that was characterized by Miss Davis’s frequent storming off sets, being suspended for refusing to act in what she considered inferior movies, and going to court to sever her ties with Warners.

But in her first three years at Warners Miss Davis made 14 films, including Edna Ferber’s ”So Big,” with Barbara Stanwyck starring, and ”20,000 Years in Sing Sing,” which was, she was to say, ”my only film with the great Spencer Tracy, to my everlasting regret.”

”He was the finest actor I ever worked with,” she said. Getting Parts, and Noticed Unafraid to Play The Villainess

She was working hard, in mostly forgettable fare, but Miss Davis was also learning the movie craft and earning the respect of technicians.

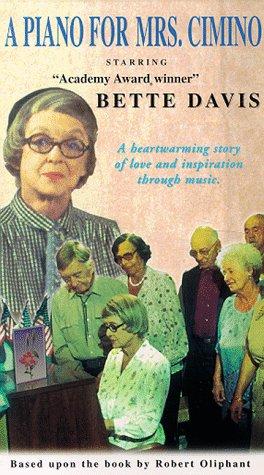

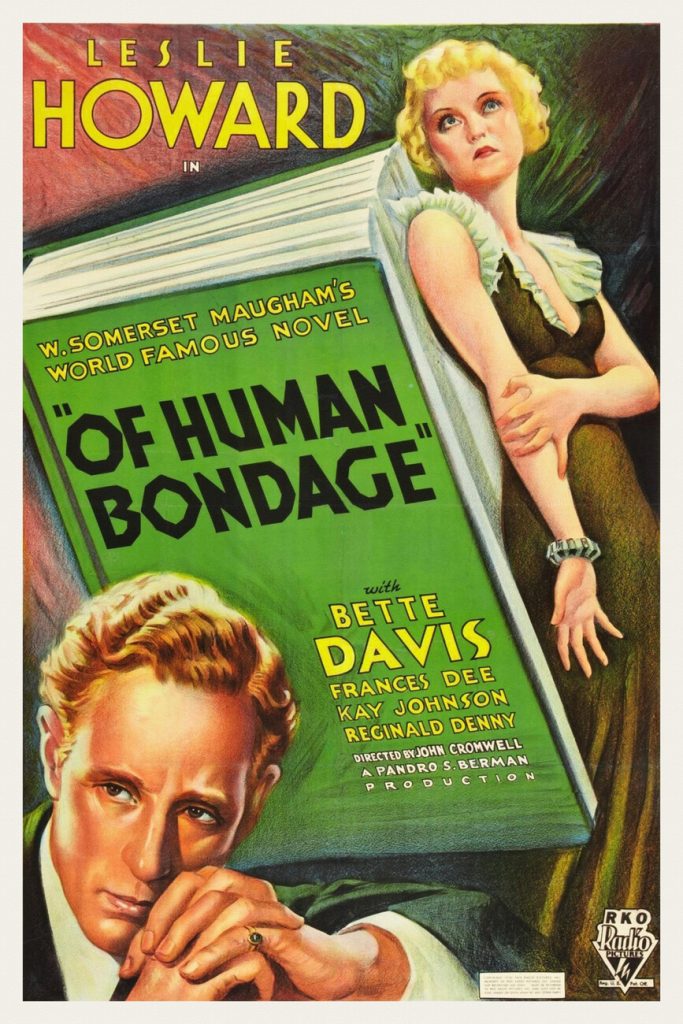

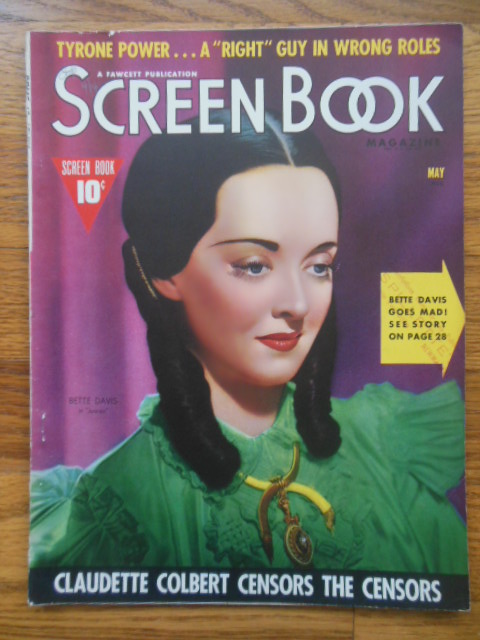

From the start Miss Davis, unlike leading ladies of the day, had no qualms about playing unsympathetic roles, and so was overjoyed in 1934 when she was lent by Warners to the rival RKO studios to play the cruel and slatternly waitress Mildred in W. Somerset Maughham’s ”Of Human Bondage,” opposite Leslie Howard as the crippled hero Philip.

”Every actor who becomes a star is usually remembered for one or two roles,” she said, ”like Judy Garland in ‘The Wizard of Oz’, Garbo in ‘Camille,’ Brando in ‘A Streetcar Named Desire.’ Mildred in ‘Of Human Bondage’ was such a role for me. She was the first leading-lady villainess ever played on a screen for real.”

”It’s odd that people remember me best for my evil roles,” she said, ”since I played so many other kinds of characters. But villains always have the best-written parts.”

She was widely praised for her performance as Mildred and nominated for an Academy Award, but she failed to win one, mostly, she said, because Warner Brothers did not want to promote an Oscar for a film it did not produce. She came to regard the Oscar that she won the next year, for ”Dangerous,” as ”a consolation prize.”

She was always proud of her two Oscars, though, and said this year: ”I’m not a bit modest about them. I don’t use those boys for door stops.”

Warners was treating her with new respect, giving her movies like ”The Petrified Forest,” with Leslie Howard and Humphrey Bogart, but Miss Davis harbored a festering resentment against what she called ”the contract slave system” at the studio.

Deciding in 1936 to defy the strictures of her contract, Miss Davis agreed with an English company to go to London to make two movies. Years later she was to ruefully confess that before she left, Jack L. Warner, the studio head, offered her a chance ”to play one of the great screen roles of all time, but I didn’t know it.”

” ‘Please don’t leave. I just bought a wonderful book for you,’ ” she quoted Mr. Warner as saying. ”And I said, ‘I’ll bet it’s a pip!’ and walked out of his office.” She learned later that the role she turned down was Scarlett O’Hara in ”Gone With the Wind.” Mr. Warner later gave up his option on it. The Glorious Years Memorable Roles, One After Another

In England, Miss Davis was sued by Warner Brothers, which succeeded in preventing her from working for another producer while under contract to Warners. But once she had returned to the United States, Warners gave her a new contract calling for fewer pictures at a much higher salary.

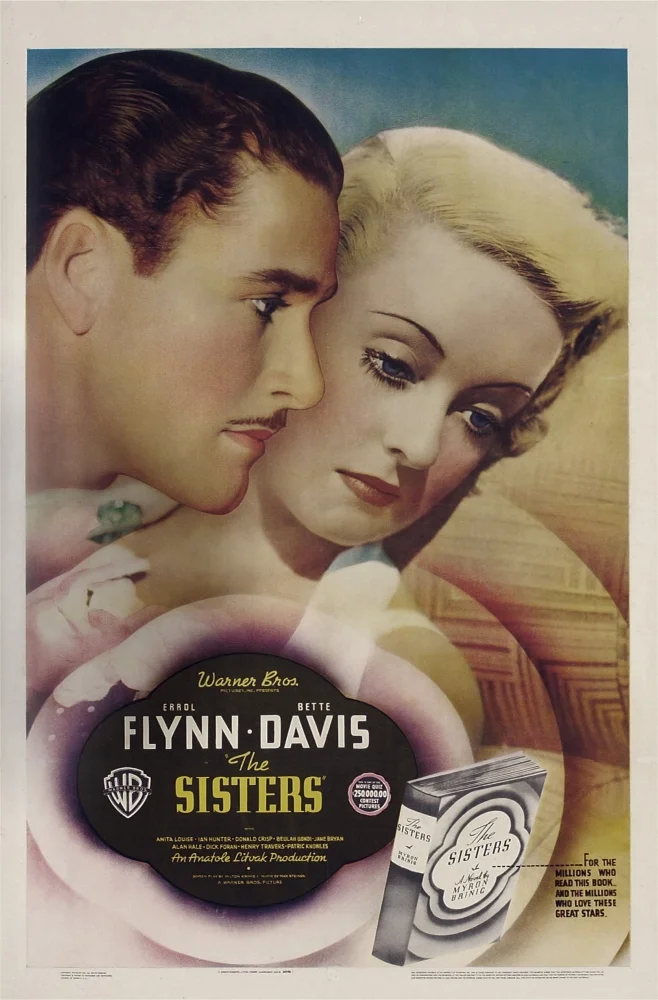

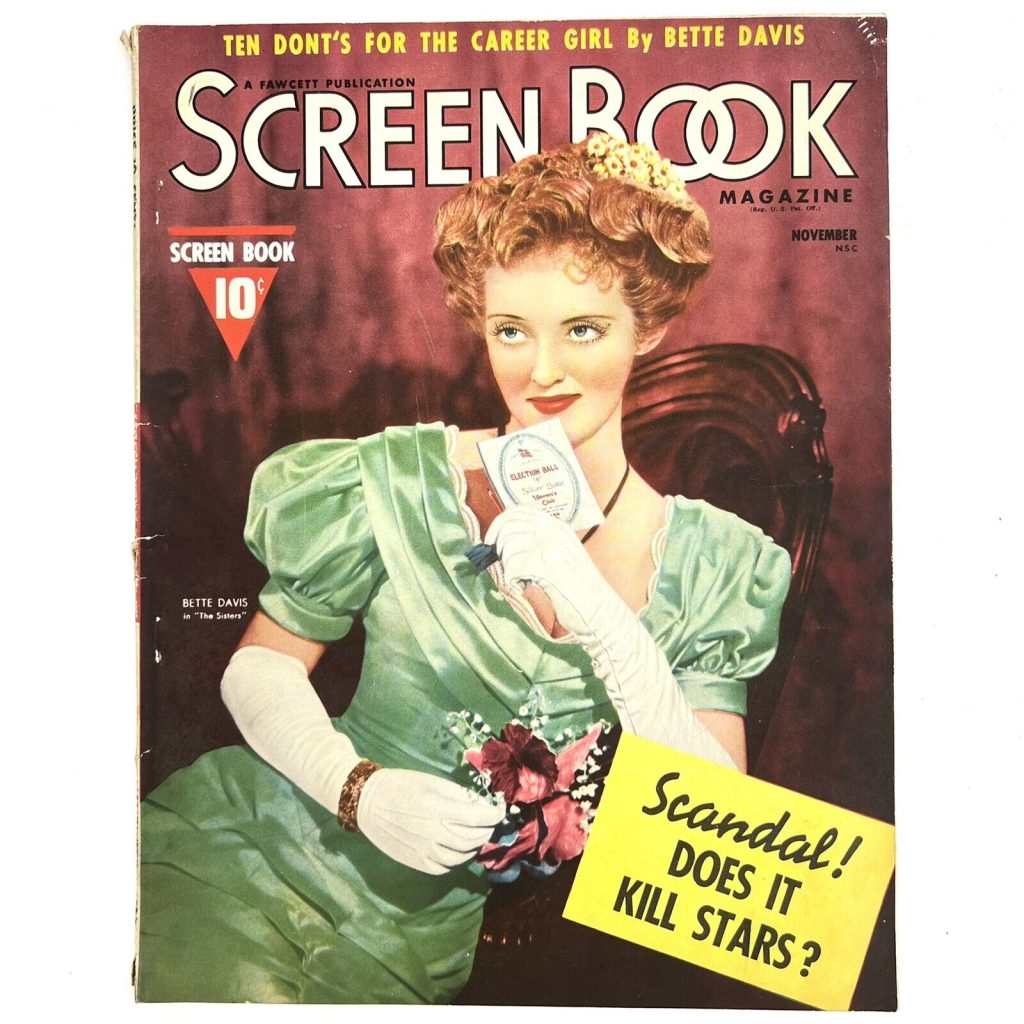

They also gave her excellent, high-budget pictures, like ”Jezebel,” for which she won her second Oscar in 1938. In a single year, 1939, Warners released no fewer than four blockbuster Davis movies: ”Dark Victory,” ”Juarez,” ”The Old Maid” and ”The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex,”

”Jezebel” began her halcyon years, she said, and ”in 1939 I secured my career and my stardom forever; I made five pictures in 12 months, and every one of them made money.”

The memorable Davis roles continued in swift order: The murderous and unfaithful planter’s wife in Maugham’s ”The Letter” in 1940, quickly followed the next year by ”The Great Lie” and ”The Little Foxes,” in which she played the scheming Regina Giddens. In 1942 she scored again in ”Now, Voyager,” as Charlotte Vale, a frumpish spinster who blossoms into a confident beauty and finds true love with Paul Henreid. The film is remembered by movie buffs for the scenes in which Mr. Henreid lights two cigarettes at once and gives one to Miss Davis.

There were other triumphs in the 1940’s – ”The Man Who Came to Dinner,” ”Watch on the Rhine,” ”Mr. Skeffington,” ”The Corn Is Green” and ”A Stolen Life.” But Miss Davis’s luck began to run out with critical and box-office disasters like ”Winter Meeting” and ”Deception,” and in 1949 Warner Brothers, after 19 years, released her from her contract while she was making the ludicrous melodrama ”Beyond the Forest.” In it a by-then plumpish Miss Davis uttered one of her most famous ”camp” lines, so often used by her mimics, ”What a dump!” Anguish and Acclaim Role of a Lifetime In ‘All About Eve’

With the end of the Warners era, Miss Davis’s third marriage, to William Grant Sherry, an artist by whom she had a daughter, Barbara Davis Sherry, was also ending. She won custody of her daughter.

Miss Davis had previously been married to Harmon Oscar Nelson Jr., a band leader, and she said in 1982 that on his insistence she had two abortions. ”That’s what he wanted,” she said. ”Being the dutiful wife, that’s what I did.” The marriage ended in divorce.

But for decades afterward, Miss Davis publicly battled with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, insisting that she had bestowed her first husband’s middle name on the Oscar. ”The Academy has fought stoically to claim that they named the Oscar,” she said. ”But of course I did. I named it after the rear end of my husband. Why? Because that’s what it looked like.”

Miss Davis’s second husband, Arthur Farnsworth, a businessman, died of head injuries suffered in a fall in 1943.

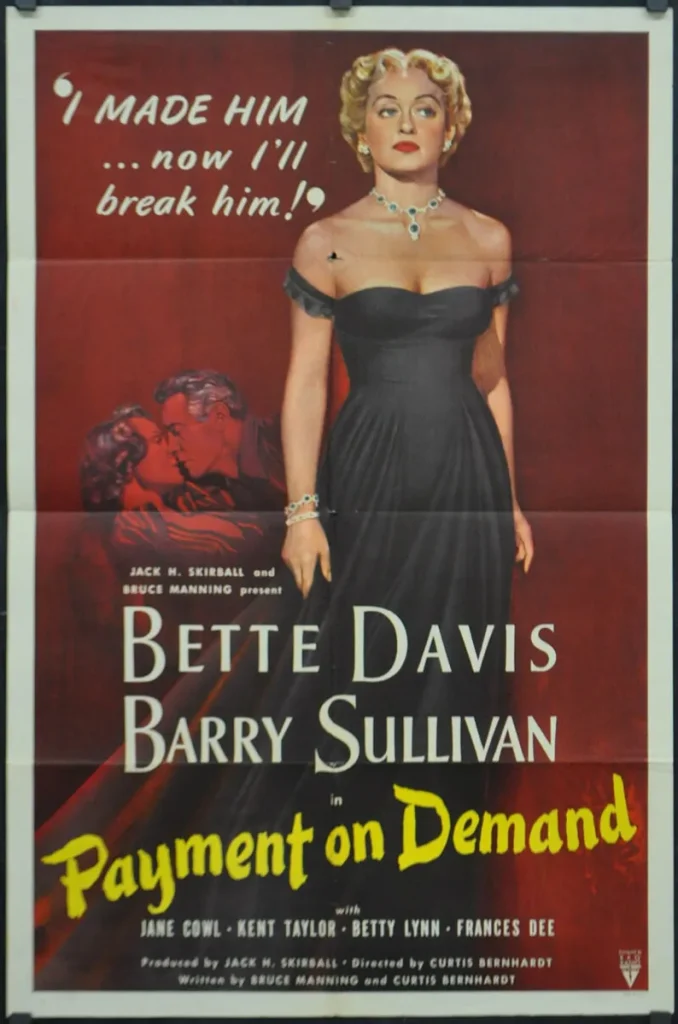

Miss Davis was filming ”Payment on Demand” in 1949 – it was not released until 1951 – when she was offered a role of a lifetime in what she was to call ”that charmed movie, ‘All About Eve.’ ” She was a last-minute replacement for Claudette Colbert, for whom the director, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, had written the role of Margo Channing, the fading Broadway star. Miss Colbert was unable to begin the film on schedule because she ”hurt her back, thank God,” as Miss Davis liked to recall it.

”When I finished reading ‘All About Eve’ I was on Cloud Nine,” said the actress. ”That night Joe Mankiewicz told me Margo Channing was the kind of dame who would treat her mink coat like a poncho.”

She played Margo that way, and brilliantly, and with the aid of a witty, literate script, sharp direction by Mr. Mankiewicz, and a sparkling cast that included Anne Baxter, Celeste Holm, George Sanders, Marilyn Monroe (in a supporting role), and Thelma Ritter, the movie became one of the all-time great Hollywood films.

During the filming of ”All About Eve,” Miss Davis became romantically involved with her leading man, Gary Merrill, and they were married in 1950. Soon afterward they adopted two children, Margot and Michael. The ‘Darkest Decade’ A Broadway Flop, A Retreat to Maine

Miss Davis received another Oscar nomination for ”The Star,” released in 1953, but the film was unsuccessful. She was by then 45 and younger actresses were being offered the parts that would have once been hers. She accepted an offer to return to Broadway in a revue, ”Two’s Company.”

When the show opened in New York in December 1952, Miss Davis recalled years later, ”The ovation was, to say the least, heartwarming, the reviews were bloodcurdling.” The revue closed after 90 performances.

Miss Davis and Mr. Merrill took an option to buy a home in Maine and, she said with wry amusement, ”We called our house Witch Way because we didn’t know which way we were going and a witch lived there. Guess who?”

”For three years I was solely a wife and mother and Gary fell out of love with me,” Miss Davis was to say years later. During that period it also became apparent that the Merrills’ adopted daughter, Margot, was retarded, and at the age of 3 she had to be put in a special school. Margot has since lived in homes for the retarded.

During what she was to call her ”darkest decade,” the 1950’s, while the the Merrills’ marriage continued to disintegrate, Miss Davis again played Elizabeth I in ”The Virgin Queen” and a year later, in 1956, appeared in Paddy Chayefsky’s ”A Catered Affair” as Ma Hurley, a Bronx housewife, which she sometimes said was her favorite role. The Merrills also traveled cross-country doing one-night stands in ”The World of Carl Sandburg” until 1960, when they were divorced. Friends and Enemies Fonda, Crawford, Cagney and Flynn

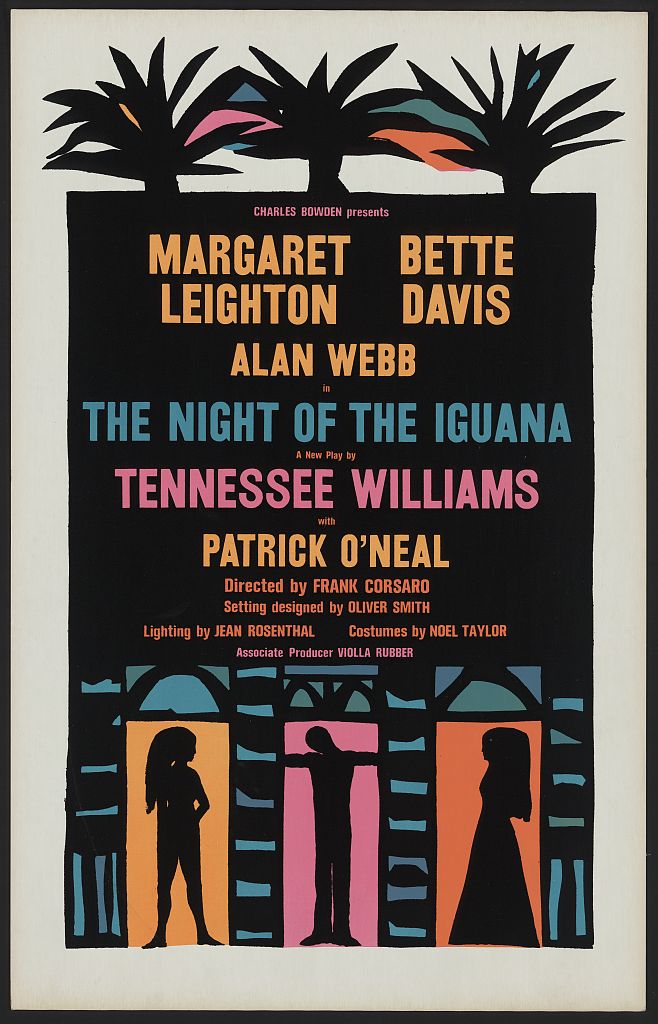

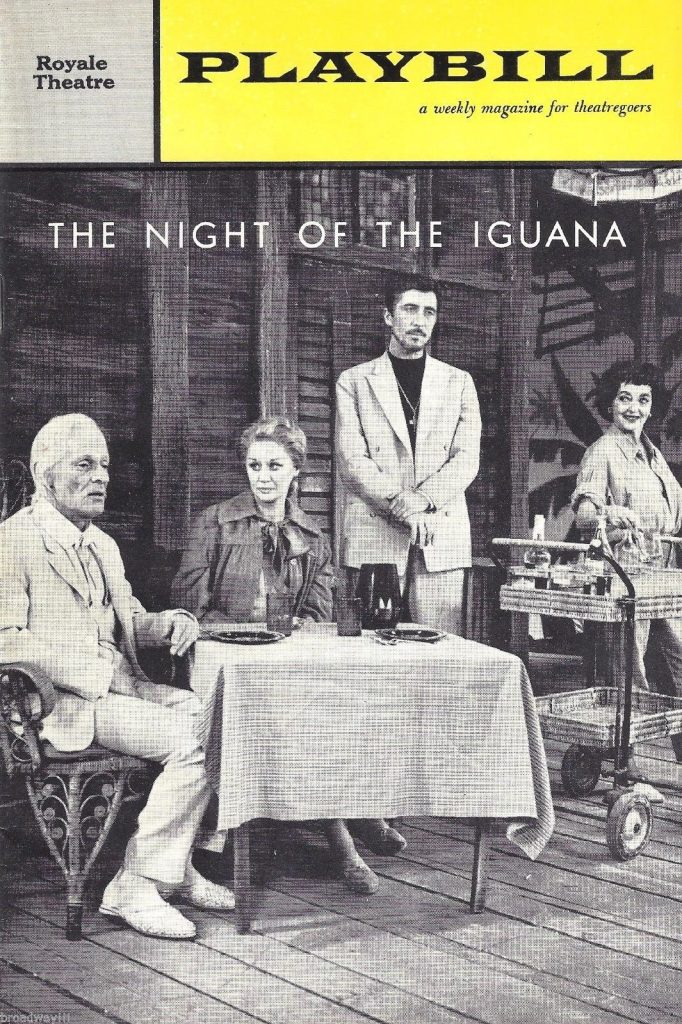

Having settled into character acting, Miss Davis in 1961 scored a success as the gin-soaked ”bag lady” Apple Annie in ”Pocketful of Miracles.” That same year she was praised for her performance on Broadway in Tennessee Wiliams’s ”The Night of the Iguana,” which she left in April 1962 to film ”Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?” a box-office winner that earned her yet another Accademy Award nomination for best actress of the year.

The horror movie, in which Miss Davis wore pasty white makeup and padded herself to appear overweight, revolved around two show-business has-been sisters living in creepy seclusion in a Hollywood mansion. The role of the loony Baby Jane Hansen, addled into thinking she was going to make a comeback in vaudeville, gave Miss Davis a chance to pull out all the acting stops, and she did so with relish. The other, wheelchair-bound, sister was played by Joan Crawford.

The casting of Miss Davis and Miss Crawford in ”Baby Jane” resuscitated longstanding rumors that they had feuded when both were Warners stars. In 1982 Miss Davis told an interviewer, ”I never feuded with Joan Crawford. During ‘Baby Jane’ the whole world hoped we would fight but we did not. We were both pros.” In any event, Miss Davis was not reticent about revealing her rancor against other performers. She accused Miriam Hopkins, with whom she co-starred in ”The Old Maid” and ”Old Acquaintance,” of upstaging her and scene-stealing. She also disliked Errol Flynn, her co-star in ”Elizabeth and Essex,” calling him ”unprofessional.”

Intense as her rivalries were, her friendships were deep and long lasting, particularly for Claude Rains, Henry Fonda, James Cagney, Paul Henreid, Olivia de Havilland, Anne Baxter and Geradine Fitzgerald.

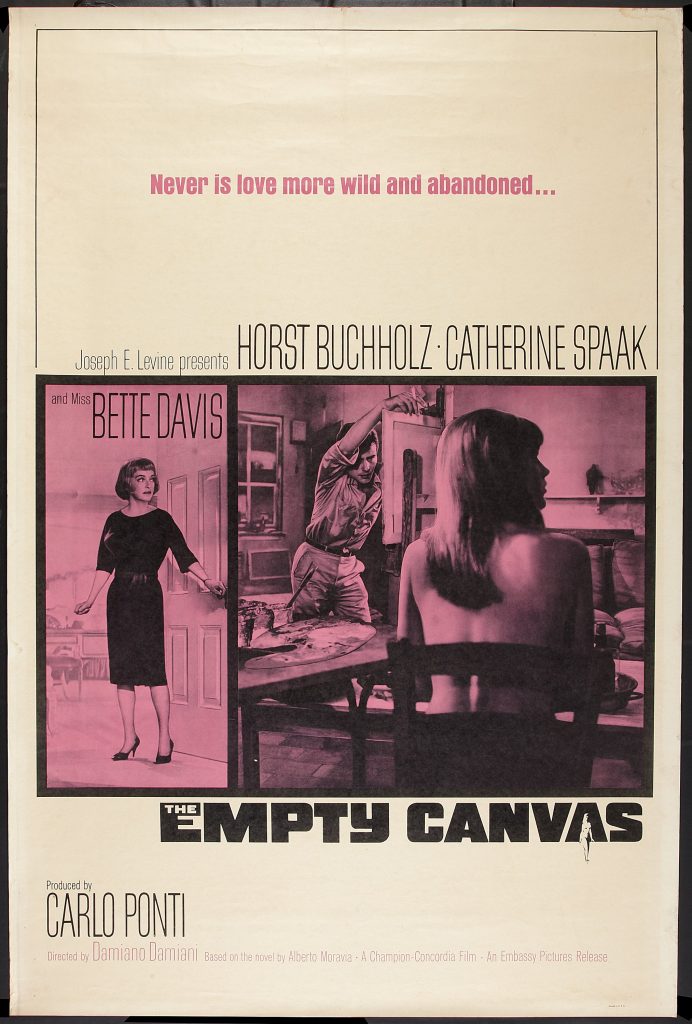

As she grew older, Miss Davis continued making movies, many of them horror thrillers or melodramas, like ”The Anniversary” (1968), in which she wore a patch over one eye.

Unlike many of her contemporaries who held out against appearing on television when it was in its infancy in the 1950’s, Miss Davis embraced it. She appeared as a guest on the Jimmy Durante comedy show, and made episodes of popular series like ”Gunsmoke” and ”Perry Mason.” Writing Her Own Epitaph ‘The Sweetness Of My Joy’

Despite advancing age Miss Davis kept on working, appearing on television and in an occasional movie, some of them made for television. She said she worked into her later years because the money came in handy, and work was part of her Yankee heritage. ”It is only work that truly satisfies,” she said. ”No one has ever understood the sweetness of my joy at the end of a good day’s work. I guess I threw everything else down the drain.”

This included her personal life, she said, adding: ”All my marriages were charades, and I was equally responsible. But I always fell in love. That was the original sin.”

It was never a secret that Miss Davis was temperamental, opinionated and often difficult to get along with, but in 1985 a scandalous book about her, by her own daughter, shocked her critics as well as her fans.

In ”My Mother’s Keeper,” B. D. Hyman portrayed Miss Davis as an abusive, domineering and hateful mother and as a grotesque alcoholic who was largely responsible for her own mistreatment by certain of her husbands. Two years later Miss Davis replied to Mrs. Hyman’s charges with her own bestseller, ‘This ‘N That,” in which she defended herself as the victim of a lying and ungrateful child. She confessed later that her estrangement from her daughter pained her.

For some years after her last divorce Miss Davis lived in Weston, Conn., but in the late 1970’s she moved into an apartment in West Hollywood.

”Indestructible,” she once said. ”That’s the word that’s often used to describe me. I suppose it means that I just overcame everything. But without things to overcome, you don’t become much of a person, do you?”

”I know what I want as my epitaph,” she said. ”Here lies Ruth Elizabeth Davis – she did it the hard way