Paul Newman’s 2008 obituary in “The Guardian”:

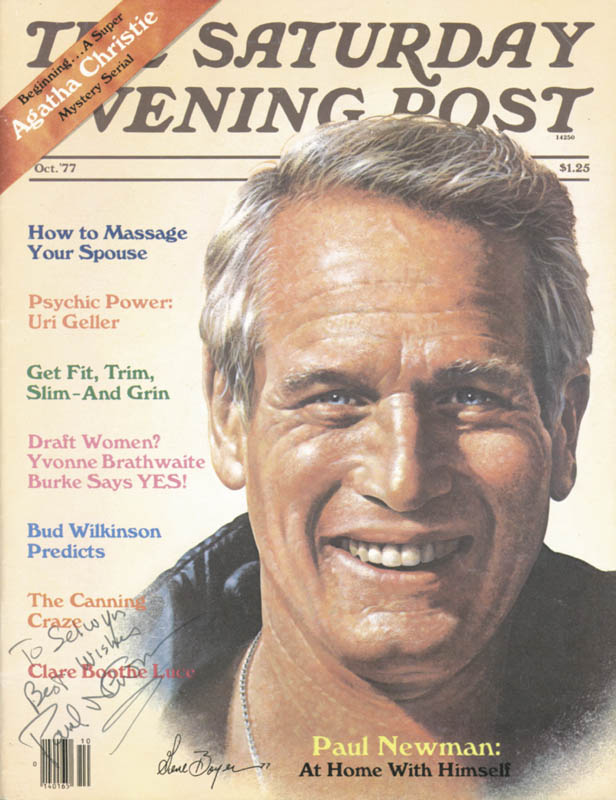

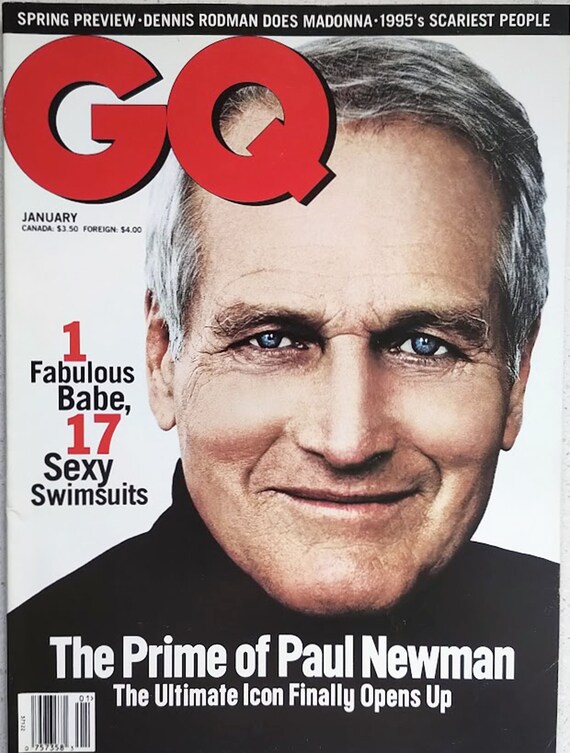

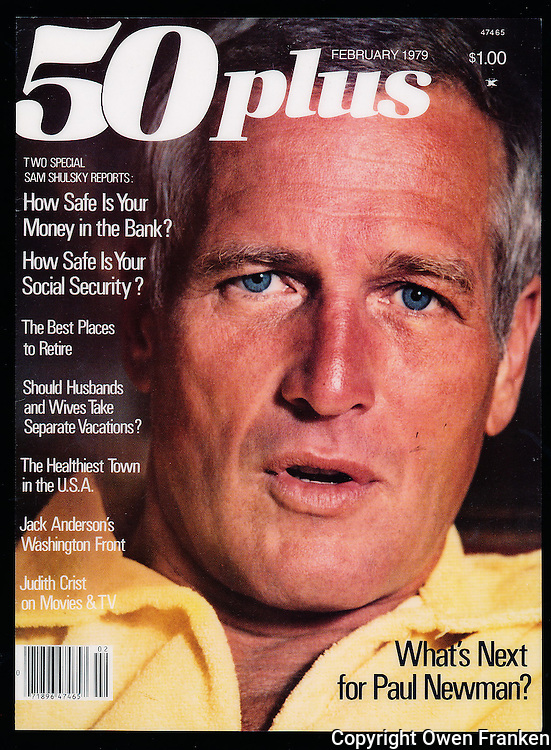

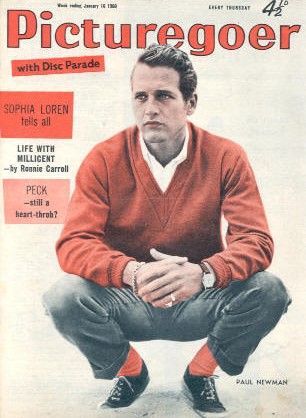

The actor Paul Newman, who has died aged 83, became so famous for his dazzling looks, and the bluest eyes in the business, that it is impossible to think of him as other than a celebrity.

Yet his many faceted, contradictory character renders the star image superficial. He was also a notable producer-director, a racing car enthusiast, a political activist and a philanthropist, counted as the person who had distributed more money – in relation to his own wealth – than any other American during the 20th century.

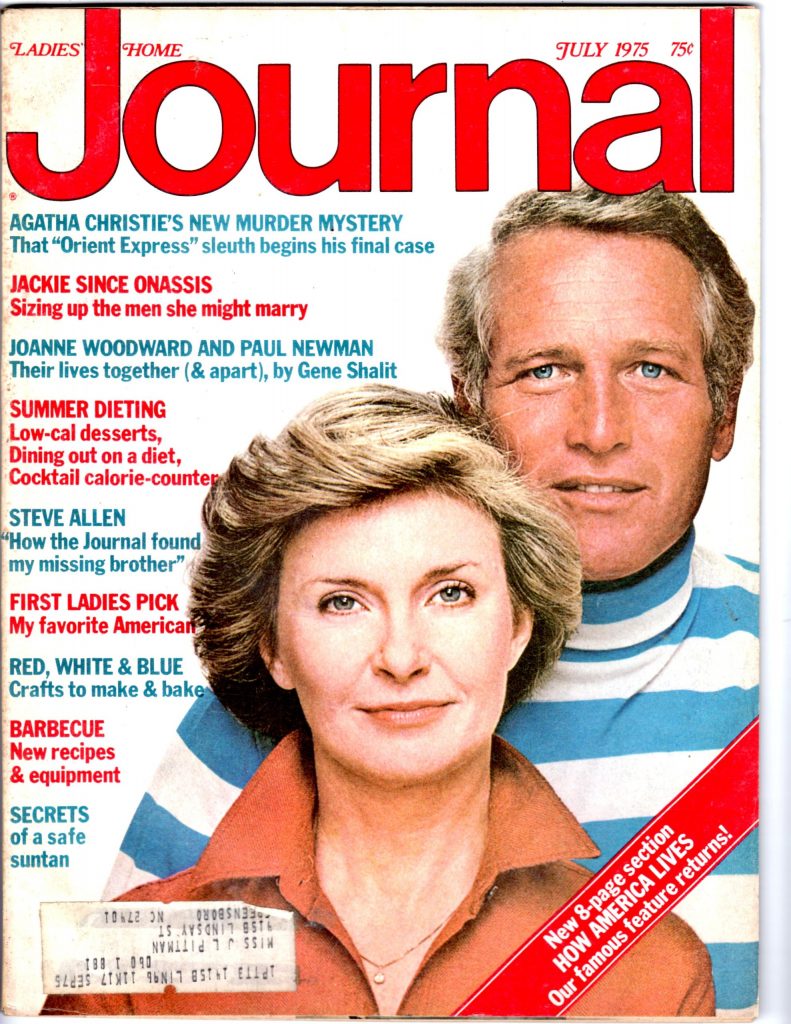

He claimed to be happiest behind the wheel of a racing car and noted that his athleticism found its perfect outlet in this sport. As a producer and co-founder of several companies, he was responsible for many of his own films and directed six features, four of them starring his second wife, Joanne Woodward. One of these gained him an Oscar nomination — one of eight, although he waited until 1986 for the coveted best actor statuette. He received two other Academy Awards, an oddly premature lifetime achievement award in 1985 and the Jean Herscholt award for his philanthropic work in 1993.

It is possible that this work may outlive his other achievements. In 1982 he founded – initially as a modest venture – the company Newman’s Own, producing products such as pasta sauces based on his own home recipes. He devoted the company’s entire profits – around $250m to date – to causes throughout the world.

Newman was actively concerned with some of the projects, including the Hole in the Wall Gang summer camps, devoted to underprivileged youngsters. He never gave up social concerns, and, in 1999, returned to the theatre in the two-hander Love Letters, where he and his wife raised hundreds of thousands of dollars to help land conservation in Connecticut.

He found time for political activities, including donating $1m to the leftist magazine The Nation, long-term involvement in civil rights issues and support for Democratic candidates. That said, his fame inevitably rested on his screen career. The star of more than 50 features, including 11 opposite Woodward, Newman, with his blue eyes, insouciant smile, and a handsome and eternally slim figure, was the idol of countless fans. His characters, such as the leads in Hud (1963) and Cool Hand Luke (1967) made him internationally famous and allowed him to enjoy the comfortable, although unostentatious, lifestyle available only to the very rich, with a main home in Connecticut, a Manhattan penthouse and a base in California.

Newman was born in Shaker Heights, Ohio, a suburb of Cleveland, the younger son of a sports store owner. His father was of Jewish-German descent and his mother was a Catholic whose family came from Hungary. She became a Christian Scientist when Paul was just five but her new beliefs did not impinge on the family and later in life Newman chose to follow none of their beliefs but, when asked, opted “for Jewishness because I considered it more challenging”.

His acting debut, aged seven, was as the court jester in Robin Hood at school. He left Shaker Heights high school in 1943 and went on briefly to Ohio University, in Athens, where he was expelled, supposedly after an incident involving a keg of beer and the rector’s car.

His comfortable life and good looks were proving a mixed blessing and wayward behaviour ended in trouble for drunkenness; there were even a couple of very brief stints behind bars. He had a lifelong liking for practical jokes.

From 1943 to 1946 Newman served as a US navy torpedo bomber radio operator. He graduated from the liberal arts Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, in 1949 and that year married for the first time — to Jacqueline Witte — and returned to Cleveland to manage the family store. His father died in 1950. But his destiny was to be an actor and he and his wife and son moved to New Haven, Connecticut, where Newman attended Yale Drama School. He had ambitions to be a drama teacher, but he was spotted at Yale by New York agents, moved to New York and had a period at the Actors’ Studio. He did a lot of television in that decade, debuting in an episode of the science fiction series Tales of Tomorrow in 1952. More importantly, chance led to a highly successful Broadway debut, originally as an understudy, in William Inge’s play Picnic (1953-54) — where he met another understudy, Woodward.

By then Hollywood had beckoned, but its call came via one of the most calamitous screen debuts ever recorded. The Silver Chalice (1954) miscast him in a toga, and so dismayed him that years later he paid for advertisements urging viewers not to watch it on television. He learned one valuable lesson — “avoid frocks” — and concentrated (except for westerns) on modern characters, often those under stress. There were few conventional romantic roles or comedies.

Recovery from his disastrous movie debut came back on Broadway in 1955, playing a gangster in The Desperate Hours. There was also plenty of television, including The Battler (1955), a Hemingway adaptation, directed by Arthur Penn, with Newman as a brain-damaged boxer, and a baseball story, Bang the Drum Slowly (1956).

Back in Hollywood he had famously lost out to James Dean when Elia Kazan screen tested them both for the lead in East of Eden. But in 1956, following Dean’s death, the role of the boxer Rocky Graziano — earmarked for Dean — in Somebody Up There Likes Me fell to him. That year, too, he starred as a brainwashed army officer in the post-Korean war drama, The Rack. Even the couple of duds which followed could not take the shine off his success. In 1957 Newman filmed The Long Hot Summer (1958), from a William Faulkner story, alongside Woodward. By January 1958 Newman was divorced from Witte, and had married his co-star.

Two more films that year confirmed his stardom. The Left Handed Gun featured Newman as Billy the Kid. They play on which it was based, written by Gore Vidal — a close friend of Newman and Woodward — had depicted Billy as gay. This theme became less explicit as the work filtered through TV, where Newman had first performed it in 1955, and in to Arthur Penn’s screen version where Billy’s relationship with his murdered mentor is left unclear.

The same thing happened with Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, where Newman played the tortured Brick opposite Elizabeth Taylor’s Maggie. As on Broadway, the homosexual theme was obscured and the reason for Brick’s marital chaos never made clear. Newman meanwhile won an Oscar nomination. In 1959 he returned to Broadway, and Tennessee Williams, in Sweet Bird of Youth. After that he effectively abandoned the theatre for 33 years, to the dismay of his wife, who believed that stage discipline would make him less reliant on his charm and the mannerisms that were — for some critics — becoming over-familiar.

In 1960 Newman starred in Otto Preminger’s vast and lumbering epic about the birth of Israel, Exodus. A year later he played a jazz musician in the intriguing Paris Blues.

Sadly, over the course of his career Newman worked with few major directors on their best films. His work with Alfred Hitchcock, Martin Scorsese, John Huston and Robert Altman was on their lesser movies. The great exception was Robert Rossen, whose classic adaptation of Walter Tevis’s novel The Hustler (1961) gave Newman his most complex early role and marked a turning point in his career. As Fast Eddie, a poolroom shark, whose innate corruptness leads to a brutal come-uppance, Newman crystallised his screen persona — a blend of vulnerability and bravado, criminality and redemption — in a performance of new found maturity. It was left to Bafta to give him its award as best actor, while the Academy passed him over for the second time. It was not until he played Eddie again opposite Tom Cruise in The Color of Money (1986) that he received the Oscar.

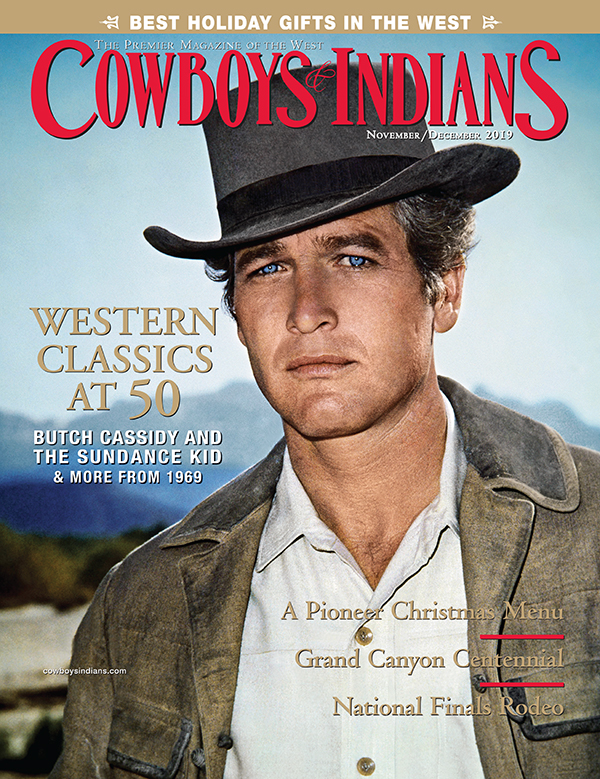

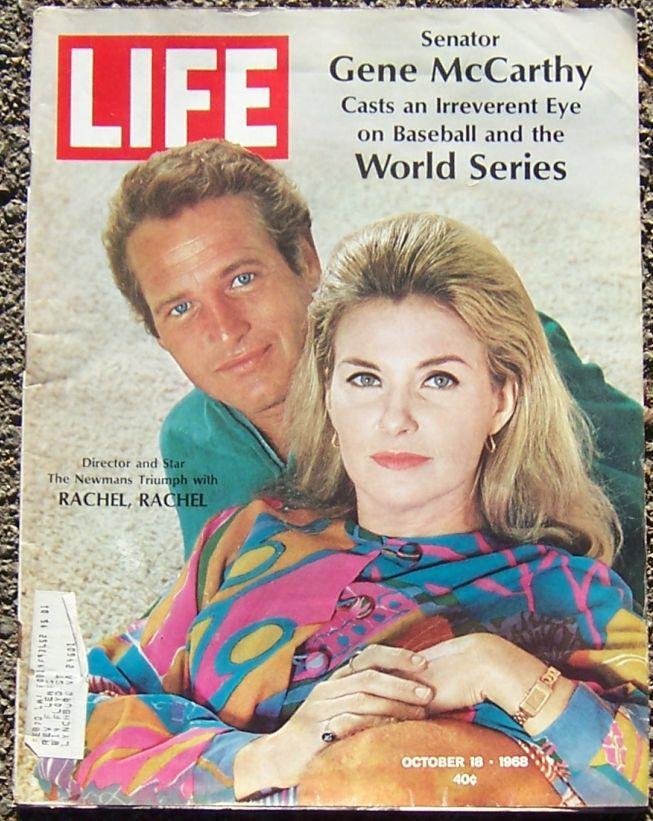

Rossen aside, Newman fared better — especially in commercial terms — with sturdy middleweight talents such as Sidney Lumet, Martin Ritt and Richard Brooks in films where what the critic Andrew Sarris memorably described as “strained seriousness” seemed to suit Newman’s own demeanour. The Hustler initiated the period that brought Newman fame and fortune, in title roles that became part of cinema legend — among them Ritt’s Hud (1963), Harper (1966), Cool Hand Luke (1967) and Butch in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) with Robert Redford. In 10 years he starred in 18 films, as well as directing his first and best movie, Rachel, Rachel (1968), starring Woodward.

Curiosities of that period included a reworking of Kurosawa’s Rashomon, retitled Outrage (1964), in which the Japanese bandit is transposed to Mexico. Newman relished another character role in an intelligent western, Hombre (1967), directed by Ritt from an Elmore Leonard story. It was compensation for Peter Ustinov’s Lady L (1965) with Sophia Loren, the Hitchcock cold war thriller Torn Curtain (1966), opposite Julie Andrews and the comedy The Secret War of Harry Frigg (1968).

He looked far happier in the Indianapolis 500 motor racing drama Winning (1969), by which time his fee for any one of his numerous movies far exceeded the $500,000 he had paid years before to extricate himself from a studio contract. Importantly, the choices he made were his own, even if there were, inevitably, duds along the way.

Many characters which he played to popular acclaim were less than admirable. Hud is selfish, Luke arrogant, Harper callous and Butch a killer. Other characters were self-obsessed (the racing driver) or wilful and on the margins of society. To such creations, even mean spirited ones, he brought a strength that made him — alongside Brando — the acceptable anti-hero of the period.

By the 1970s Newman had become more overtly political. He was one of the narrators of the documentary King: a Filmed Record … from Montgomery to Memphis (1970), about Martin Luther King, and also in that year starred in the anti-radical right drama WUSA. His support for the King documentary was one aspect of his support for civil rights. He also campaigned against the war in Vietnam and had supported Eugene McCarthy’s 1968 bid for the presidency. He was vigorous in his opposition to Richard Nixon and proud of being among the top 20 on Nixon’s “most hated” list.

Newman never lost his commitment to liberal causes, but like his exact contemporary Charlton Heston, whose raucous support for the gun lobby, and the right, diametrically opposed Newman’s philosophy, he found that overt politicising sometimes misfired. People came to see him, not always to support the cause. He found greater satisfaction as part of the team involved with his charitable foundation.

At the height of his fame Newman formed one of several production companies he was to be associated with. Barbra Streisand, Sidney Poitier, Steve McQueen and later Dustin Hoffman joined him to set up the First Artists title in 1969. Each agreed to make three movies and Newman — possibly with less ego than most of his partners — fulfilled his promise.

In 1972, Pocket Money revived his Luke character in all but name. He then made The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, distractedly directed by his friend Huston during the early throes of one of his many marriages. Finally, in 1975, he revived the Lew Harper detective in a rather sadistic thriller, The Drowning Pool. Soon after, First Artists was wound up and the actor found himself looking for roles that suited a star now into handsome middle age.

His box office credibility had been maintained by two smash hits The Sting (1973), which reunited him with Redford, and The Towering Inferno (1974), where he received top billing.

Of his two films with Robert Altman, Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or, Sitting Bull’s History Lesson (1976) is by far the more successful, but the bizarre futuristic drama Quintet (1979) ended the decade disastrously, a flop compounded by the awfulness of When Time Ran Out (1980). His fans had not taken to the raucous and foul-mouthed Slap Shot (1977), another work which had indicated Newman’s search for more original material.

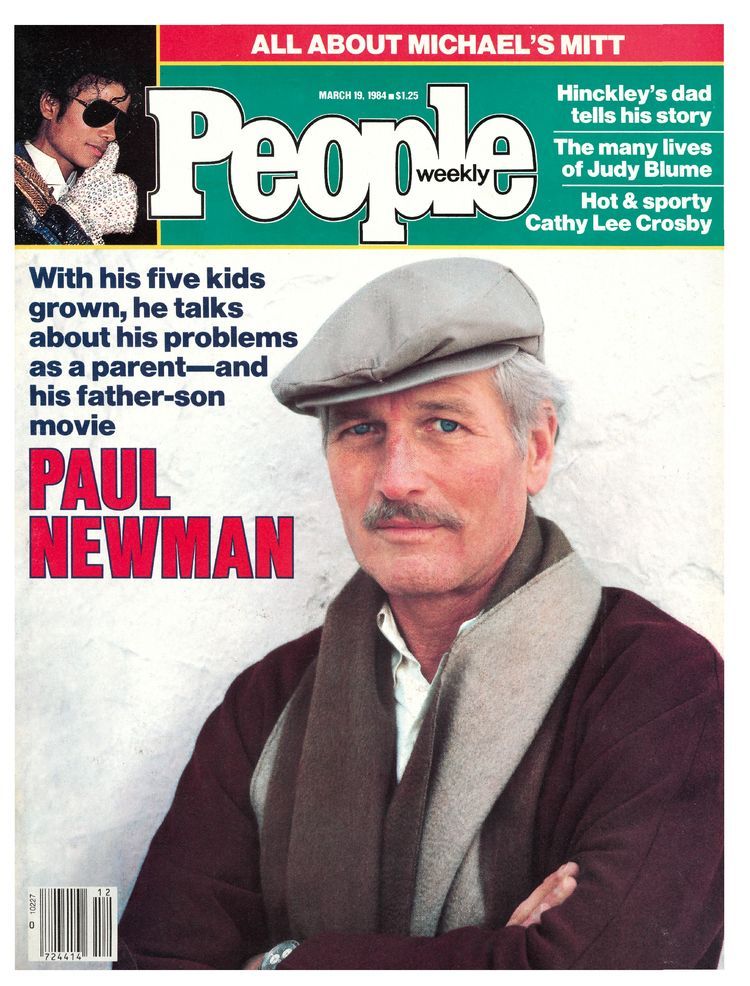

He had returned to direction in 1971, salvaging the outdoor drama Sometimes a Great Notion. The following year he produced and directed a vehicle for his wife and daughter Nell, The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds. He was to render her better service 15 years later when he directed The Glass Menagerie (1987), “to immortalise Joanne’s performance”. His other stints as director were a competently made television film, from the play The Shadow Box (1980), and four years later a more personal work Harry & Son. This movie, which gave him his only writing credit (plus star, producer and director), was a highly charged family drama about the difficult relationship between Harry and his teenage son.

The subject was almost too close to Newman, whose first child Scott had died of a drug overdose in 1978. Newman felt deeply distressed by his death and the overwrought Harry & Son meant more to its creator than to the general audience.

During the 1980s Newman settled into character roles and in 1981 enjoyed success as a tough street cop in Fort Apache, the Bronx. But the cop, like his crane driver Harry, asked us to believe in Newman as a working-class hero and lacked the credibility he brought to Absence of Malice (1981) and The Verdict (1982). Both earned him Oscar nominations. The latter had a screenplay by David Mamet and presented him with a juicy role as a fading, alcoholic lawyer. A part which, as his director Sidney Lumet remarked, required only minimal research.

The star had an acknowledged taste for alcohol and despite giving up spirits in mid-career (with a lapse after his son’s death), enjoyed his beer and displayed a deep appreciation of vintage wine. I recall having lunch with him one day at his London hotel suite when he particularly liked a white Burgundy. He called the restaurant and ordered the rest of the case to be put in his refrigerator.

Bizarrely, his intense performance in The Verdict failed to gain him an Oscar — a fact taken harder by his wife than by the star. It was suggested that his politics and residence on the east coast since 1962 had alienated him from the conservative Hollywood establishment. In compensation — after he had taken a year off to concentrate on his motor racing — he was awarded, aged 60, an honorary Oscar for his lifetime achievement, normally reserved for the truly venerable within the profession. The following year he chose not to attend the awards ceremony — only to win best actor for The Color of Money.

Alongside the accolades, there were other less successful movies, such as Blaze and Fat Man and Little Boy (both 1989). In the former he starred as Earl Long, the philandering 1950s governor of Louisiana. His necessarily strident performance failed to ignite a dull movie. The second work personalised the story of General Groves, the belligerently professional officer who oversaw the Manhattan Project which developed the allied atomic weapons programme. Duller than either of these was Mr & Mrs Bridge (1990), in which he and Woodward wilted under James Ivory’s direction.

Newman took a long time out of acting and away from conventional Hollywood. Then, in 1994, he had a villainous supporting role in the Coen brothers’ satire on big business The Hudsucker Proxy and the lead in Nobody’s Fool. Both reminded audiences of his talent. In the latter, he played a grouch unable to relate to his own son but drawn to his shy grandson — a touching relationship which, the director Robert Benton noted, drew heavily on Newman’s own character. The performance gained him another Oscar nomination. Despite this success, he again stayed away from film work except to narrate Baseball (1994) and a 1997 TV series, Super Speedway.

In 1995, aged 70, he took part in the 24-hour Daytona endurance race — becoming the oldest person ever to complete the event, capping his 1979 success when he and his co-driver finished second in the 24-hour Le Mans race. After Daytona, he agreed to quit professional racing and to the relief of his wife opted for his Volvo.

Four years after Nobody’s Fool, Benton coaxed him back to the studio to star in Twilight (1998), to play an ageing, cynical private detective with a drink problem. The part was tailor-made for Newman, who brought a gravel-voiced and somewhat melancholy charm to the character. Despite a fine cast, the film had a tired feel to it and showed signs of severe post-production pruning.

The movie marked a flurry of activity for Newman and he followed it with Message in a Bottle (1999), a tear-jerker in which he played Kevin Costner’s crotchety, alcoholic father — scooping the best reviews, not least for his commanding presence, but also for a willingness to play his age. He again took third billing to decidedly lesser names in Where the Money Is (1999), proving, if proof were needed, that after decades of stardom he was a dedicated professional first and a star a long way second.

Newman returned to a substantial film role in Sam Mendes’s Road to Perdition (2002). He was cast atypically as the vicious gang boss Rooney who commits a murder witnessed by the small son of one of his henchmen (Tom Hanks). Set in the 1930s, the movie was heavy on atmosphere and menace, provided by Newman and his contract killer, Jude Law. It brought him yet another Oscar nomination and rave reviews.

No roles of similar quality followed, but back on stage he scored a hit in 2002 as the Stage Manager in Thornton Wilder’s Our Town and reprised it on television the following year, with Woodward as executive producer.

His final acting appearance was in the prestige television drama Empire Falls, directed by Fred Schepisi from the award-winning novel by Richard Russo, writer of both Twilight and Nobody’s Fool. He was executive producer and won an outstanding actor Emmy.

In 2007 he announced, “I think acting is pretty much a closed book to me.” Yet his voice could be still be heard on a number of short cartoons, as the character Doc Hudson, both in Cars and Mater and the Ghostlight, and finally the Indy Car Series Preview for 2008, showing that his love of motor racing had never left him. In June 2007, he donated $10m dollars from his charitable foundation to Kenyon College from where he had graduated all those years ago. The endowment created the largest scholarship in the history of the college, but it was just one more act that earned him the justified reputation as one of Hollywood’s good guys, as well as one of its greatest actors.

He is survived by his wife Joanne and their three daughters and two daughters from his first marriage.

Paul Leonard Newman, actor, born January 26 1925; died September 26 2008

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.