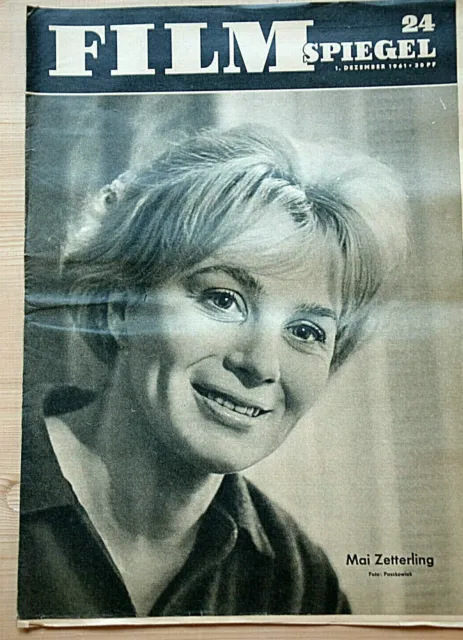

David Shipman’s obituary of Mai Zetterling in “The Independent”:

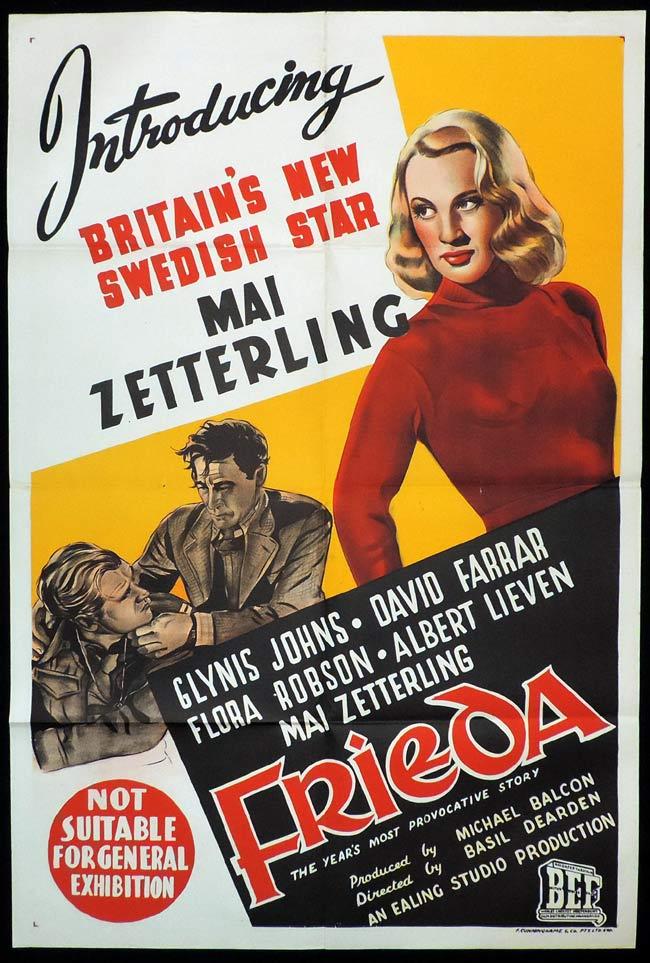

‘WOULD you take Frieda into your home?’ So went one of the most famous movie ad-lines of the post-war period. Frieda (1947) was the story of a German war bride and the prejudice she encountered when her husband, played by David Farrar, brought her home to the small town where he lived. It was directed by Basil Dearden for Ealing, a studio much admired for tackling topical issues.

Ealing might have argued that her notices for Hets (Frenzy, 1945) had proved that the critics adored her – she was certainly much admired for her performance as Bertha, the tobacconist’s assistant who seduces the schoolboy hero (Alf Kjellin) while pursuing his sadistic teacher (Stig Jarrel). It was written by Ingmar Bergman – his first work in movies – for the established Alf Sjoberg, who reunited his two young stars in Iris och Lojtnantishjarta (Iris).

Bergman, meanwhile, had become a director and cast Zetterling in Musik Morker (Night Is My Future/ Music Is My Future, 1948), in which she again played a maid who falls in love with the young master, Birger Malmsten. Though melodramatic, the film contains early echoes of Bergman’s richness.

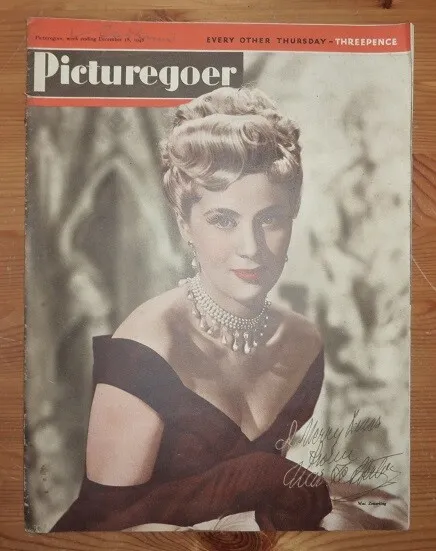

Trained, like Ingrid Bergman, at the Royal Dramatic Theatre School in Stockholm, Zetterling might have sought a career like hers in the United States, but there were probably not sufficient roles for two leading Swedish actresses. Ealing, however, believed that Zetterling could be a big star for them. This was the heyday of period romances and the studio’s first Technicolor film was to be Saraband for Dead Lovers (1948), based on a novel by Helen Simpson about the adulterous affair between a Swedish mercenary (Stewart Granger) and Sophie Dorothea, the consort of the Elector of Hanover who became George I. But when Zetterling became pregnant the role went to Joan Greenwood.

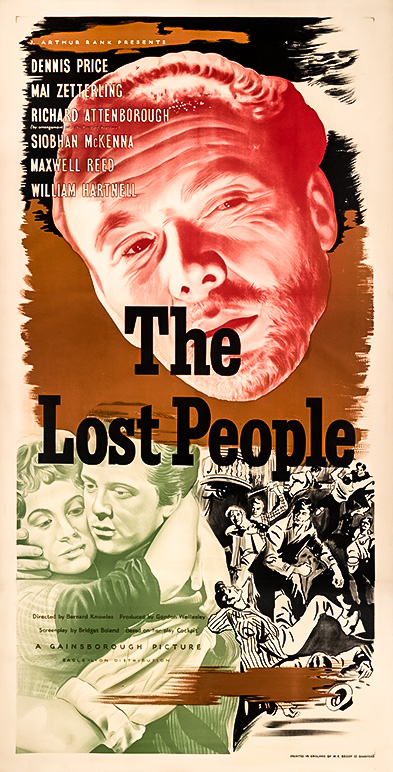

Zetterling looked like being a leading British star and in rapid succession played displaced persons in two movies set in contemporary Germany, Terence Fisher’s Portrait from Life (1948) and Bernard Knowles’s The Lost People (1949). These were produced by Gainsborough, smarting from the knowledge that critics disliked their escapist entertainment. Aiming again at respectability the studio came up with The Bad Lord Byron (1949), directed by David MacDonald with Dennis Price in the title-role, in which Zetterling played Byron’s Italian mistress Teresa Guiccioli. In what had been her second British picture Quartet (1948), a collection of four Somerset Maugham short stories, Zetterling had been unconvincing as a Riviera adventurist in the first of them, The Facts of Life. The Romantic Age (1949) was such sub-standard farce that it seriously damaged her film career.

However, the touching talent displayed in her Swedish films and Frieda found a congenial home on the West End stage. She had played supporting roles in classical plays in Stockholm; in London she scored such a critical success as Hedwig in The Wild Duck that the limited run of two months sold out the day after the first night. Later in 1948 Tennants cast her as Nina in The Seagull, with Paul Scofield as Constantin and Isabel Jeans as Arkadina, initially at the Lyric, Hammersmith, and then in the West End. Also at the Lyric for Tennants, she gave strong and subtle performances in Jean Anouilh’s Point of Departure (1950), as Eurydice to Dirk Bogarde’s Orpheus, and in A Doll’s House (1953), as Nora. She returned memorably to this theatre in 1959 to play Strindberg’s Tekla in Creditors.

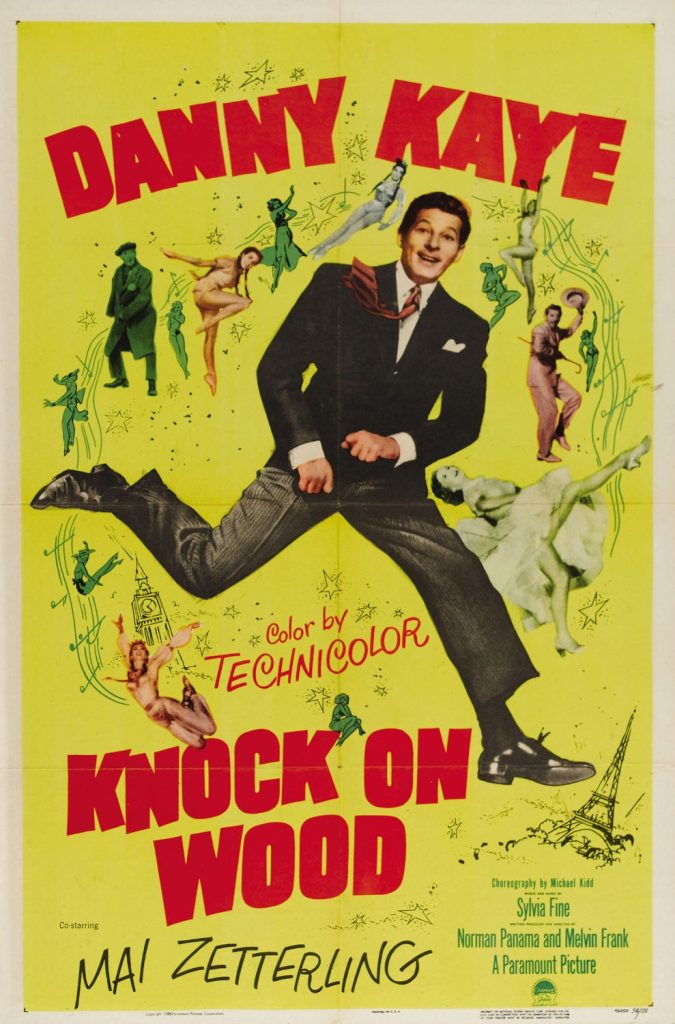

In the meantime Hollywood had called and she starred opposite Danny Kaye in Knock on Wood (1954), playing a Swiss psychoanalyst who follows him to London to continue to treat him. She became romantically involved with Kaye, as she did with Tyrone Power when he came to Britain to make Seven Waves Away; she also persuaded him to play opposite her in the television Miss Julie.

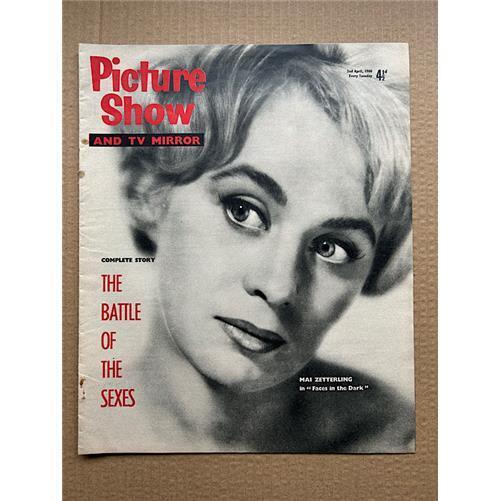

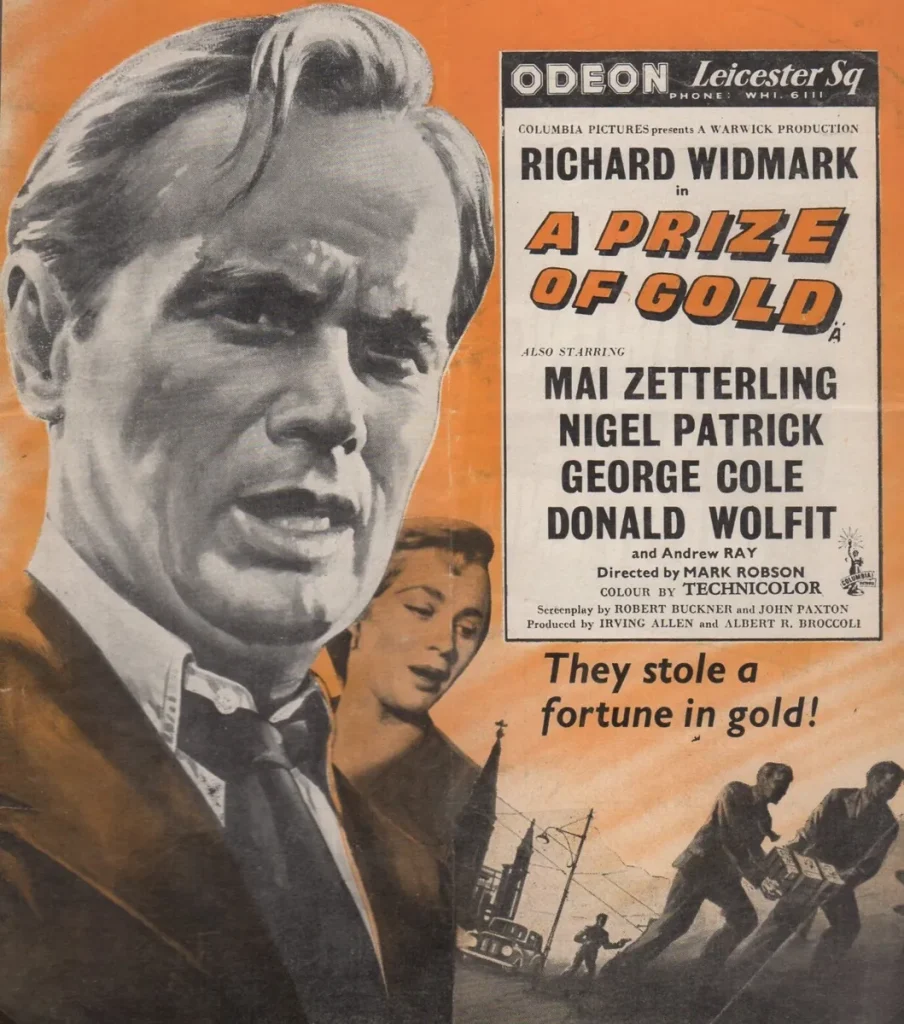

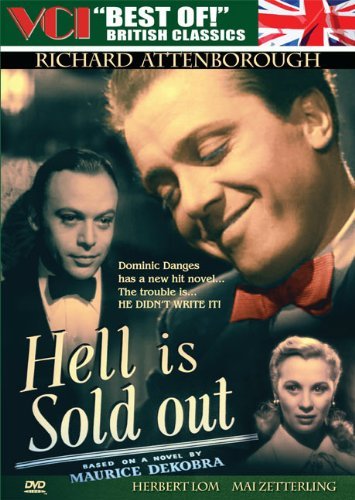

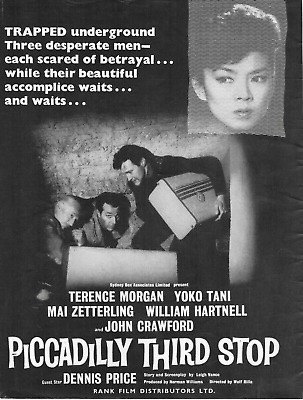

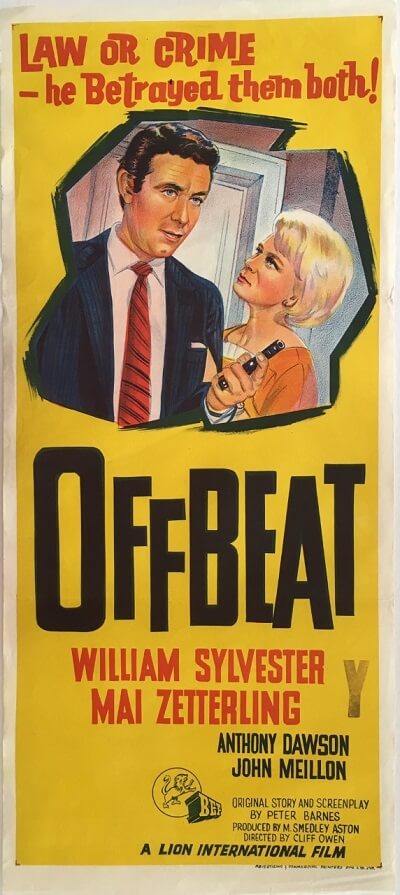

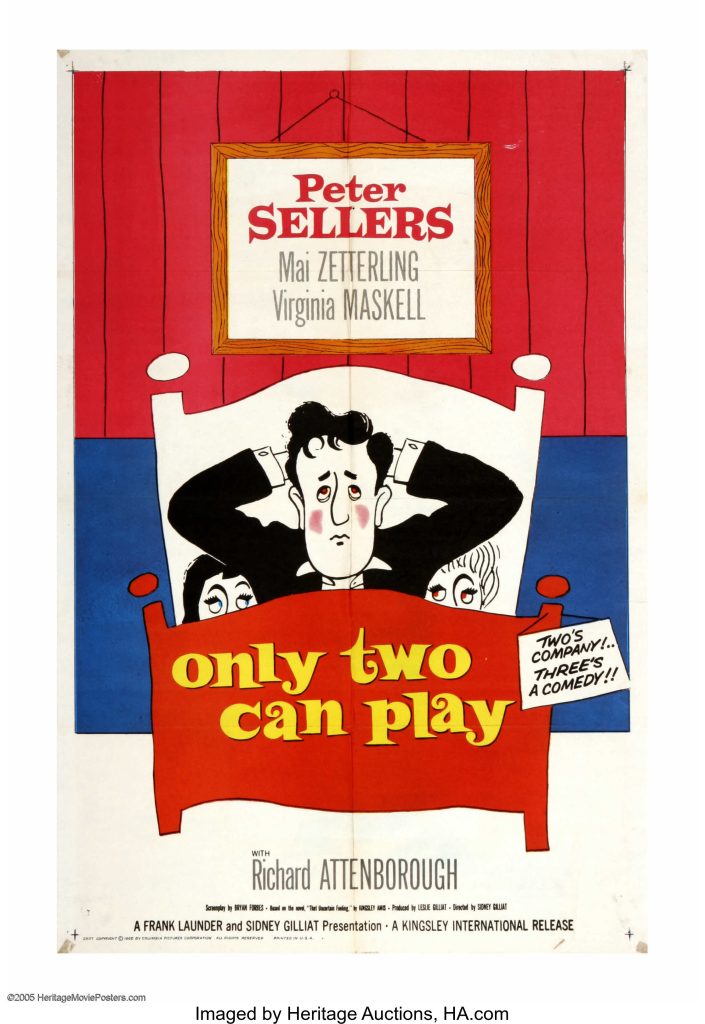

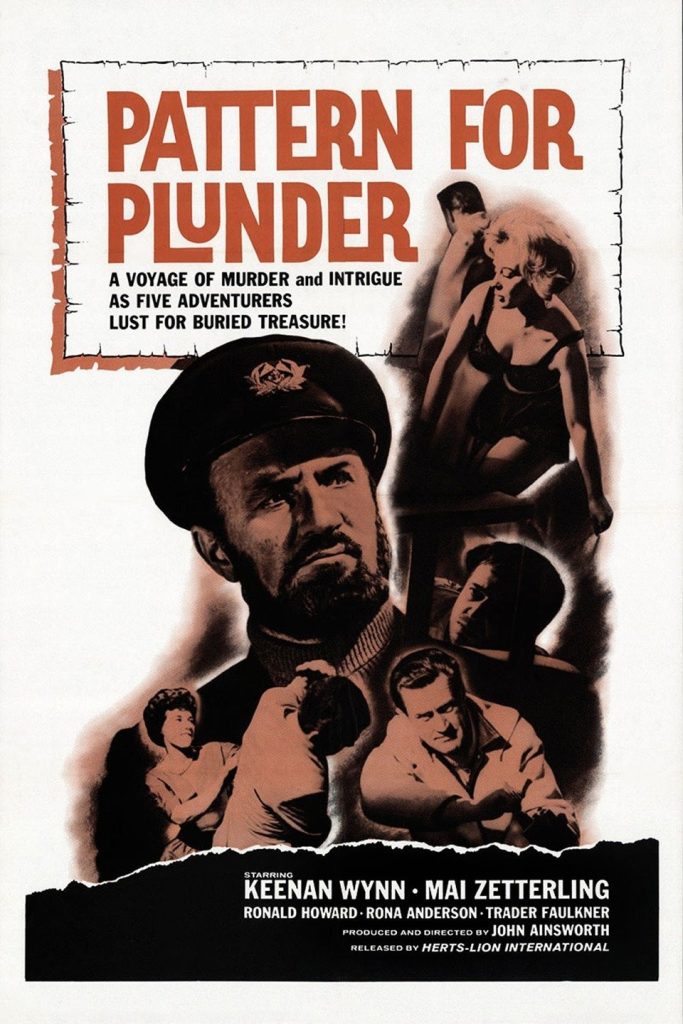

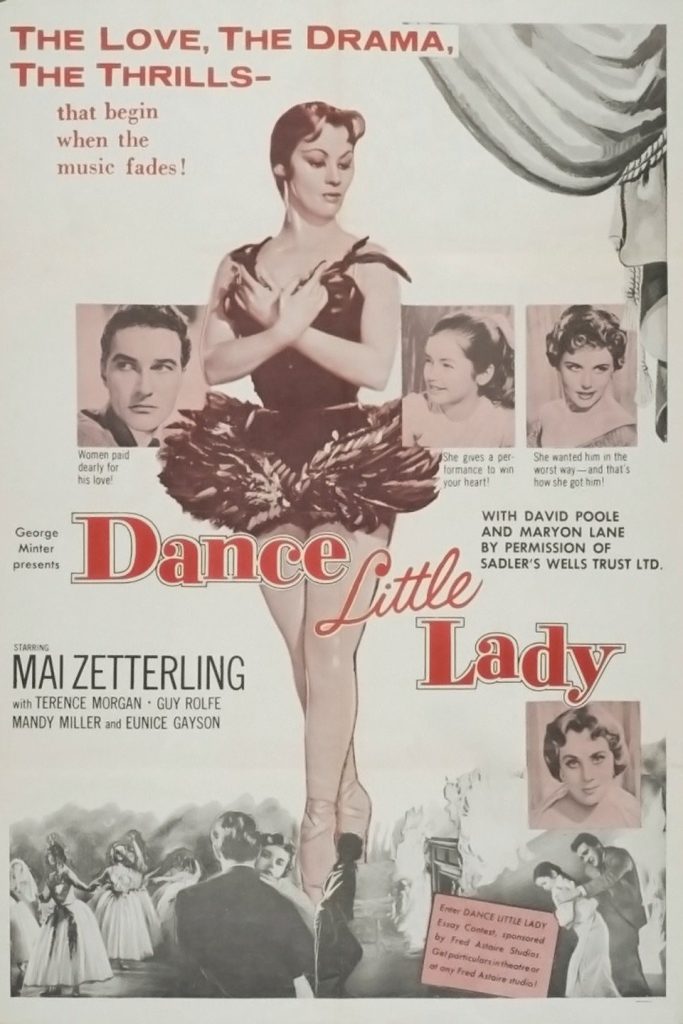

There were several other British movies, some of them backed by Hollywood: and although most of them were undistinguished she remained a ‘name’ throughout the world. Her last leading role at this time was one of her successful seductresses, the provincial wife who makes a play for the librarian Peter Sellers in Sidney Gilliat’s Only Two Can Play (1961).

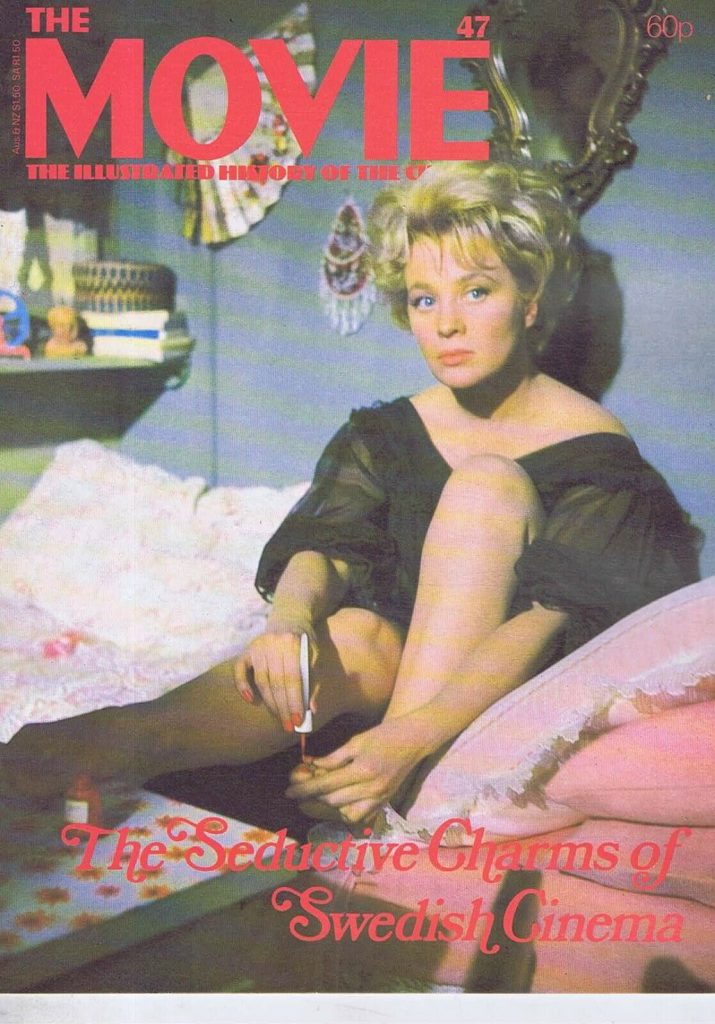

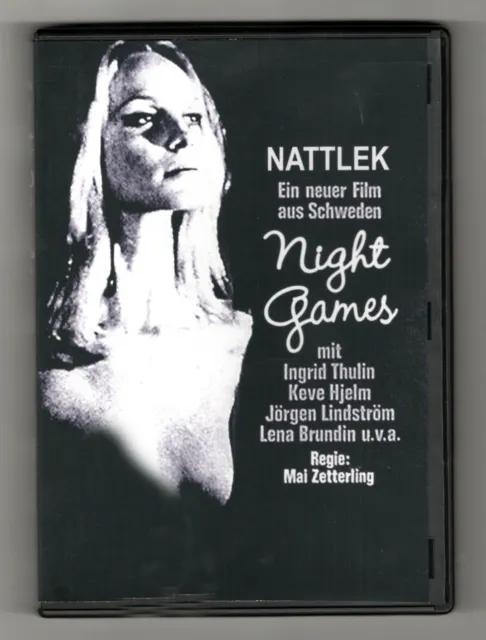

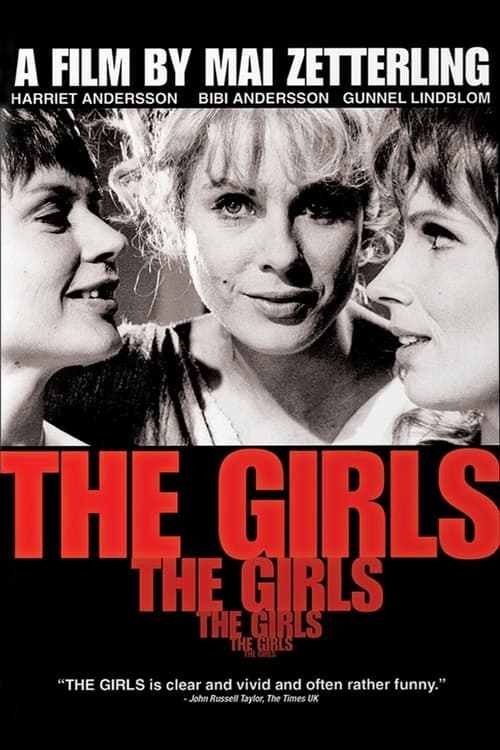

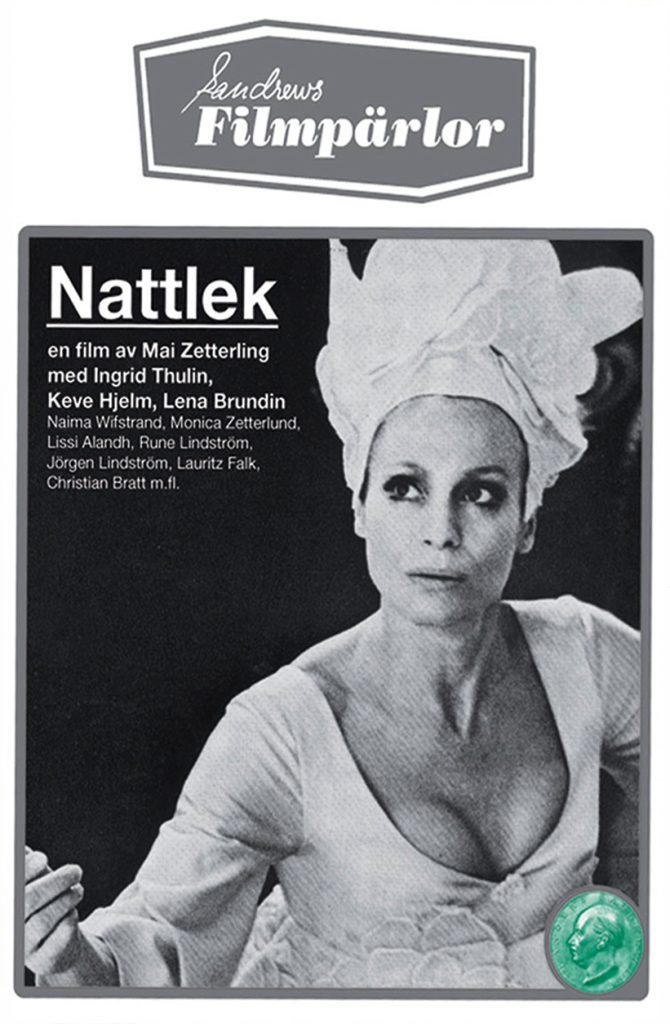

Zetterling, a woman of intelligence and fierce independence, decided not to sit around and wait for offers. She directed a short documentary, The War Game (1963), which won a Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. She returned to Sweden to direct Alskande Par (Loving Couples, 1964), a story of expectant mothers strongly influenced by Bergman and acted by some of his stock company, and Nattlek (Night Games, 1966), influenced this time by Strindberg as a disturbed man recalls his mother-dominated childhood. She also wrote the first of these, with her then husband, the novelist David Hughes, and the second she wrote alone from her own novel.

She continued to direct in Sweden and as her films became more feminist and more explicit they did not attract an undivided army of admirers. A British picture about two Borstal girls, Scrubbers (1982), created much controversy. Her last two films as an actress were Nicolas Roeg’s The Witches (1989) and Hidden Agenda (1990), Ken Loach’s brave film about Northern Ireland. That was only a small role, playing an anti-British activist, but one of which she was proud.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.