Obituary from “The Guardian”:

The career of the actor Barrie Ingham, who has died aged 82, was so varied that you might have thought he had several incarnations: as an associate artist with the Royal Shakespeare Company, in British and Broadway musicals, and as the voice of the sleuth rodent Basil in Disney’s animated mystery movie The Great Mouse Detective (1986), tracking his archenemy, voiced by Vincent Price.

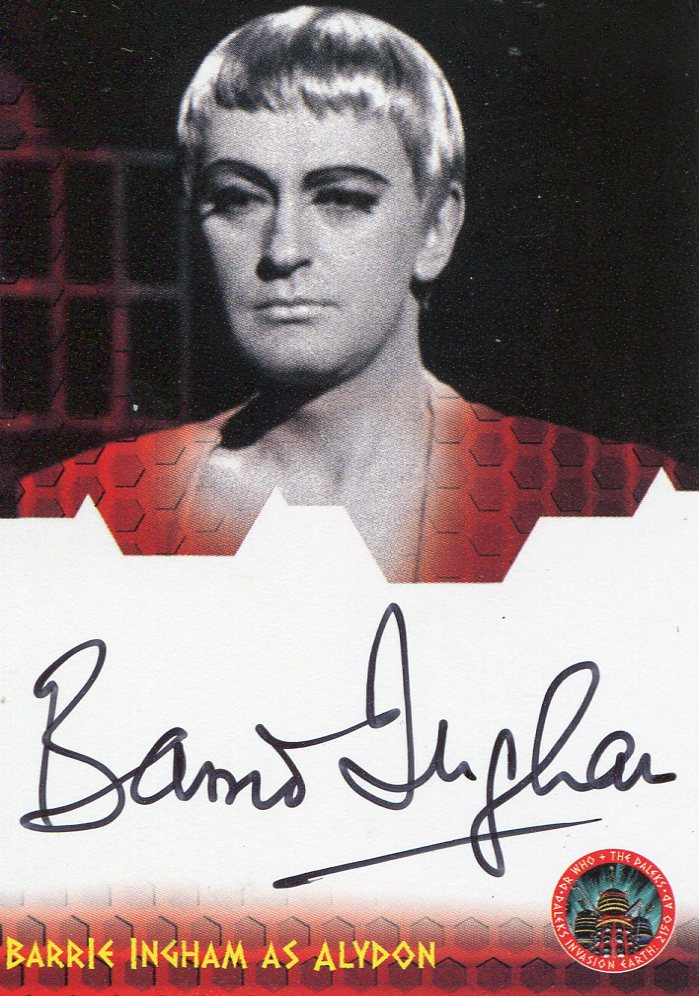

No one looked more like a leading man: Ingham was tall, handsome, ramrod straight – he served as an officer in the Royal Artillery during his national service – with a fine singing voice. Naturally gifted, he was equally adept in farcical sitcom or stylish high comedy.

He was born in Halifax, West Yorkshire, the only son of Harold Ingham and his wife, Irene (nee Bolton), who owned a furniture store in the town, and was educated at Heath grammar school, which, during the second world war, hosted the local amateurs, the Halifax Thespians. Barrie joined them as a teenager and remembered seeing, across the road from his bedroom, the bust of Shakespeare outside the new Halifax Playhouse, converted from a Wesleyan chapel, which opened in 1949.

After national service, he worked in the family business before making his professional debut in 1956 at the Pier Pavilion, Llan- dudno, in Arnold Ridley’s Beggar My Neighbour. He met the actor Tarne Phillips at the St Helens TheatreRoyal on Merseyside, where they played romantic leads in Johnny Belinda, Rebecca and Jane Eyre; they married in 1957.

Ingham went on to play a season at the Library theatre in Manchester. He joined the Old Vic at the end of 1957 and played Fortinbras to John Neville’s Hamlet; this was followed by increasingly important roles. So he was an ideal Claudio whenJohn Gielgud was invited to open the 1959 Broadway season with a revival of his celebrated Much Ado About Nothing – in which Gielgud played Benedick opposite Margaret Leighton as Beatrice.

Back in Britain in 1960, Ingham toured with Maggie Smith, Michael Bates and Michael Blakemore in Strip the Willow by Beverley Cross (“an odd play,” said Blakemore, “derived from drawing-room comedy and Peter Ustinov”) and appeared in John Arden’s The Happy Haven at the Royal Court, a comedy set in an old people’s home where the actors wore masks. Neither play was a success, but they illustrated the theatre of the day, on a tipping point between old and new.

In that decade of convulsive change, Ingham steered a course through the middle (though he did play, rather daringly, both Stavrogin in Dostoevsky’s The Possessed and Dionysus in The Bacchae of Euripides at the Mermaid theatre), appearing with Harry Secombe in the musical Pickwick (1964) at the Saville and, at the same theatre two years later, as Clancy Pettinger in On the Level, a charming but soon to be obsolete type of musical, by Ronald Millar (the playwright who later became a speechwriter for Margaret Thatcher) and Ron Grain

He was prominent in two fine TV series of the late 1960s, The Caesars and The Power Game – ancient and modern versions of the same thing , perhaps – and made a mark in films such as Gordon Flemyng’s Dr Who and the Daleks (1965) and Hammer’s A Challenge for Robin Hood (1967), in which he played the title role. Then he refocused and joined the RSC for four years (1967-71) in Stratford-upon-Avon and London. He played Leontes opposite Judi Dench in Trevor Nunn’s nursery all-white The Winter’s Tale, Brutus in Julius Caesar and Lord Foppington in The Relapse. With Dench and Donald Sinden, he appeared in two of the greatest productions of that era, John Barton’s Twelfth Night (as Aguecheek) and Dion Boucicault’s London Assurance.

His musical theatre skills served the 1973 London premiere of Gypsy, in which he played Herbie the manager opposite first Angela Lansbury and then Dolores Gray, both sensational, at the Piccadilly. He was Smith’s husband in a short run of a not very funny comedy about sexually transmitted disease, Snap (the title Clap was deemed unsuitable), by Charles Laurence, at the Vaudeville in 1974.

When he rejoined the RSC later in the same year, as the Duke “of dark corners” in Measure for Measure, he was made an associate artist of the company, but he only returned to the fold once thereafter, stealing the notices as Beverley Carlton, a brilliant send-up of Noël Coward, in an otherwise misfired 1989 revival at the Barbican of the Broadway classic The Man Who Came to Dinner.

Three years before, at the National Theatre, he had appeared in David Hare’s The Bay at Nice (opposite Irene Worth) and as the wise narrator of Arthur Miller’s episodic Depression play The American Clock. But he was increasingly peripatetic, touring a solo show to Australia, making sitcoms in Los Angeles and appearing on Broadway as King Pellinore in a revival of Camelot, as Sir George Dillingham in Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Aspects of Love, and then for four years (1997-2001) as Sir Danvers Crew in a musical Jekyll and Hyde by Frank Wildhorn and Leslie Bricusse.

We lost sight of him – he undertook big American tours of Me and My Girl, Aspects of Love and Camelot – but he returned to the West End in Trevor Nunn’s glorious 2003 resuscitation of Cole Porter and PG Wodehouse’s Anything Goes, and as a fruity old boyfriend of Maureen Lipman’s dotty diva Florence Foster Jenkins in Peter Quilter’s Glorious! directed by Alan Strachan at the Birmingham Rep and the Duchess (2005).

Ingham latterly settled in Palm Springs, Florida, where he performed and lectured on Shakespeare.

He is survived by Tarne, and their four daughters, Catrin, Liane, Francesca and Mali, and eight grandchildren.